by Rick O'Connor | Dec 17, 2021

EDRR Invasive Species

Black and White Argentine Tegu

(Salvator merianae)

The Argentine Black and White Tegu.

Photo: EDDMapS.org

Define Invasive Species: must have all of the following –

- Is non-native to the area, in our case northwest Florida

- Introduced by humans, whether intentional or accidental

- Causing either an environmental or economic problem, possibly both

Define EDRR Species: Early Detection Rapid Response. These are species that are either –

- Not currently in the area, in our case the Six Rivers CISMA, but a potential threat

- In the area but in small numbers and could be eradicated

Native Range:

The Argentine Black and White Tegu is native to South America.

Introduction:

The tegu was introduced to Florida through the pet trade. Some animals either escaped or were released.

EDDMapS currently list 7,014 records of the Argentine Black and White Tegu in the U.S. 5,908 (84%) are from Miami-Dade County. There are 12 records from Georgia and one from Memphis Tennessee. The majority of records are from south Florida.

There are 12 records from the Florida panhandle and five within the Six Rivers CISMA. The only confirmed breeding pairs are in Miami-Dade, Hillsborough, and Charlotte counties in Florida.

Description:

Tegus are long black and white banded lizards that can reach four feet in length. They prefer high dry sandy habitats but can be found in a variety of habitats including agricultural fields.

Issues and Impacts:

Basically… they eat everything. Being omnivores, stomach analysis indicates they will feed on fruits, vegetables, eggs, insects, and small animals. These animals include lizards, turtles, snakes, lizards, and small mammals. They feed primarily on ground dwelling creatures. A typical tegu clutch will have 35 eggs.

The consumption of fruits and vegetables can have a major impact on agricultural row crops throughout Florida. Their habit of consuming eggs would include the American alligator, the American crocodile, and the gopher tortoise – all protected species.

Records show the number of tegus trapped each year is growing, with over 1400 captured in 2019. This suggests the populations are increasing and new breeding colonies are probable. There are also records of the animal in north Florida and Georgia, suggesting they can tolerate the colder winters of those regions.

Management:

Management is currently with trapping. Both the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission and their subcontracted trappers are currently the primary method of removing the animals. Researchers from the University of Florida as well as those mentioned above frequently conduct roadside surveys searching for these animals. We ask anyone who has seen a tegu to report it on the IveGotOne App found on the EDDMapS website – www.eddmaps.org – or the website itself, and call your local extension office.

For more information on this EDRR species, contact your local extension office.

References

Control of Invasive Tegus in Florida. The Croc Docs. https://crocdoc.ifas.ufl.edu/projects/Argentineblackandwhitetegus/

Harvey, R.G., Dalaba, J.R., Ketterlin, J., Roybal, A., Quinn, D., Mazzotti, F.J. 2021. Growth and Spread of the Argentine Black and White Tegu Population in Florida. University of Florida IFAS Electronic Data Information System. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/UW482

Harvey, R.G., Mazzotti, F.J. 2015. The Argentine Black and White Tegu in South Florida; Population, Spread, and Containment. University of Florida IFAS Publication WEC360.

https://crocdoc.ifas.ufl.edu/publications/factsheets/tegufactsheet.pdf

Johnson, S.A., McGarrity, M. 2020. Florida Invader: Tegu Lizard. University of Florida Wildlife Ecology Conservation. WEC295. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdf/UW/UW34000.pdf

Early Detection and Distribution Mapping System (EDDMapS)

https://www.eddmaps.org/

Six Rivers CISMA

https://www.floridainvasives.org/sixrivers/

by Daniel J. Leonard | Nov 18, 2020

The native Florida landscape definitely isn’t known for its fall foliage. But as you might have noticed, there is one species that reliably turns shades of red, orange, yellow and sometimes purple, it also unfortunately happens to be one of the most significant pest plant species in North America, the highly invasive Chinese Tallow or Popcorn Tree (Triadica sebifera).

Chinese Tallow fall foliage. Photo courtesy of Daniel Leonard.

Native to temperate areas of China and introduced into the United States by Benjamin Franklin (yes, the Founding Father!) in 1776 for its seed oil potential and outstanding ornamental attributes, Chinese Tallow is indeed a pretty tree, possessing a tame smallish stature, attractive bark, excellent fall color and interesting white “popcorn” seeds. In addition, Chinese Tallow’s climate preferences make it right at home in the Panhandle and throughout the Southeast. It requires no fertilizer, is both drought and inundation tolerant, is both sun and shade tolerant, has no serious pests, produce seed preferred by wildlife (birds mostly) and is easy to propagate from seed (a mature

Chinese Tallow tree can produce up to 100,000 seeds annually!). While these characteristics indeed make it an awesome landscape plant and explain it being passed around by early American colonists, they are also the very reasons that make the species is one of the most dangerous invasives – it can take over any site, anywhere.

While Chinese Tallow can become established almost anywhere, it prefers wet, swampy areas and waste sites. In both settings, the species’ special adaptations allow it a competitive advantage over native species and enable it to eventually choke the native species out altogether.

In low-lying wetlands, Chinese Tallow’s ability to thrive in both extreme wet and droughty conditions enable it to grow more quickly than the native species that tend to flourish in either one period or the other. In river swamps, cypress domes and other hardwood dominated areas, Chinese Tallow’s unique ability to easily grow in the densely shaded understory allows it to reach into the canopy and establish a foothold where other native hardwoods cannot. It is not uncommon anymore to venture into mature swamps and cypress domes and see hundreds or thousands of Chinese Tallow seedlings taking over the forest understory and encroaching on larger native tree species. Finally, in waste areas, i.e. areas that have been recently harvested of trees, where a building used to be, or even an abandoned field, Chinese Tallow, with its quick germinating, precocious nature, rapidly takes over and then spreads into adjacent woodlots and natural areas.

Chinese tallow seedlings colonizing a “waste” area. Photo courtesy of Daniel Leonard.

Hopefully, we’ve established that Chinese Tallow is a species that you don’t want on your property and has no place in either landscapes or natural areas. The question now is, how does one control Chinese Tallow?

- Prevention is obviously the first option. NEVER purposely plant Chinese Tallow and do not distribute the seed, even as decorations, as they are sometimes used.

- The second method is physical removal. Many folks don’t have a Chinese Tallow in their yard, but either their neighbors do, or the natural area next door does. In this situation, about the best one can do is continually pull up the seedlings once they sprout. If a larger specimen in present, cut it down as close to the ground as possible. This will make herbicide application and/or mowing easier.

- The best option in many cases is use of chemical herbicides. Both foliar (spraying green foliage on smaller saplings) and basal bark applications (applying a herbicide/oil mixture all the way around the bottom 15” of the trunk. Useful on larger trees or saplings in areas where it isn’t feasible to spray leaves) are effective. I’ve had good experiences with both methods. For small trees, foliar applications are highly effective and easy. But, if the tree is taller than an average person, use the basal bark method. It is also very effective and much less likely to have negative consequences like off-target herbicide drift and applicator exposure. Finally, when browsing the herbicide aisle garden centers and farm stores, look for products containing the active ingredient Triclopyr, the main chemical in brands like Garlon, Brushtox, and other “brush/tree & stump killers”. Mix at label rates for control.

Despite its attractiveness, Chinese Tallow is an insidious invader that has no place in either landscapes or natural areas. But with a little persistence and a quality control plan, you can rid your property of Chinese Tallow! For more information about invasive plant management and other agricultural topics, please contact your local UF/IFAS Extension office!

References:

Langeland, K.A, and S. F. Enloe. 2018. Natural Area Weeds: Chinese Tallow (Sapium sebiferum L.). Publication #SS-AGR-45. Printer friendly PDF version: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/AG/AG14800.pdf

by Shep Eubanks | Sep 13, 2019

Common Salvinia Covering Farm pond in Gadsden County

Photo Credit – Shep Eubanks UF/IFAS Gadsden County Extension

Close up of common Salvinia

Photo Credit – Shep Eubanks UF/IFAS Gadsden County Extension

Aquatic weed problems are common in the panhandle of Florida. Common Salvinia (Salvinia minima) is a persistent invasive weed problem found in many ponds in Gadsden County. There are ten species of salvinia in the tropical Americas but none are native to Florida. They are actually floating ferns that measure about 3/4 inch in length. Typically it is found in still waters that contain high organic matter. It can be found free-floating or in the mud. The leaves are round to somewhat broadly elliptic, (0.4–1 in long), with the upper surface having 4-pronged hairs and the lower surface is hairy. It commonly occurs in freshwater ponds and swamps from the peninsula to the central panhandle of Florida.

Reproduction is by spores, or fragmentation of plants, and it can proliferate rapidly allowing it to be an aggressive invasive species. When these colonies cover the surface of a pond as pictured above they need to be controlled as the risk of oxygen depletion and fish kill is a possibility. If the pond is heavily infested with weeds, it may be possible (depending on the herbicide chosen) to treat the pond in sections and let each section decompose for about two weeks before treating another section. Aeration, particularly at night, for several days after treatment may help control the oxygen depletion.

Control measures include raking or seining, but remember that fragmentation propagates the plant. Grass carp will consume salvinia but are usually not effective for total control. Chemical control measures include :carfentrazone, diquat, fluridone, flumioxazin, glyphosate, imazamox, and penoxsulam.

For more information reference these IFAS publications:

Efficacy of Herbicide Active ingredients Against Aquatic Weeds

Common salvinia

For help with controlling Common salvinia consult with your local Extension Agent for weed control recommendations, as needed.

by Laura Tiu | Mar 6, 2019

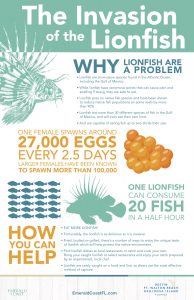

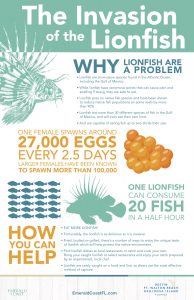

The northwest Florida area has been identified as having the highest concentration of invasive lionfish in the world. Lionfish pose a significant threat to our native wildlife and habitat with spearfishing the primary means of control. Lionfish tournaments are one way to increase harvest of these invaders and help keep populations down.

Located in Destin FL, and hosted by the Gulf Coast Lionfish Tournaments and the Emerald Coast Convention and Visitors Bureau, the Emerald Coast Open (ECO) is projected to be the largest lionfish tournament in history. The ECO, with large cash payouts, more gear and other prizes, and better competition, will attract professional and recreational divers, lionfish hunters and the general public.

You do not need to be on a team, or shoot hundreds of lionfish to win. Get rewarded for doing your part! The task is simple, remove lionfish and win cash and prizes! The pretournament runs from February 1 through May 15 with final weigh-in dockside at AJ’s Seafood and Oyster Bar on Destin Harbor May 16-19. Entry Fee is $75 per participant through April 1, 2019. After April 1, 2019, the entry fee is $100 per participant. You can learn more at the website http://emeraldcoastopen.com/, or follow the Tournament on Facebook.

The Emerald Coast Open will be held in conjunction with FWC’s Lionfish Removal & Awareness Day Festival (LRAD), May 18-19 at AJ’s and HarborWalk Village in Destin. The Festival will be held 10 a.m. to 5 p.m each day. Bring your friends and family for an amazing festival and learn about lionfish, taste lionfish, check out lionfish products! There will be many family-friendly activities including art, diving and marine conservation booths. Learn how to safely fillet a lionfish and try a lionfish dish at a local restaurant. Have fun listening to live music and watching the Tournament weigh-in and awards. Learn why lionfish are such a big problem and what you can do to help! Follow the Festival on Facebook!

“An Equal Opportunity Institution”

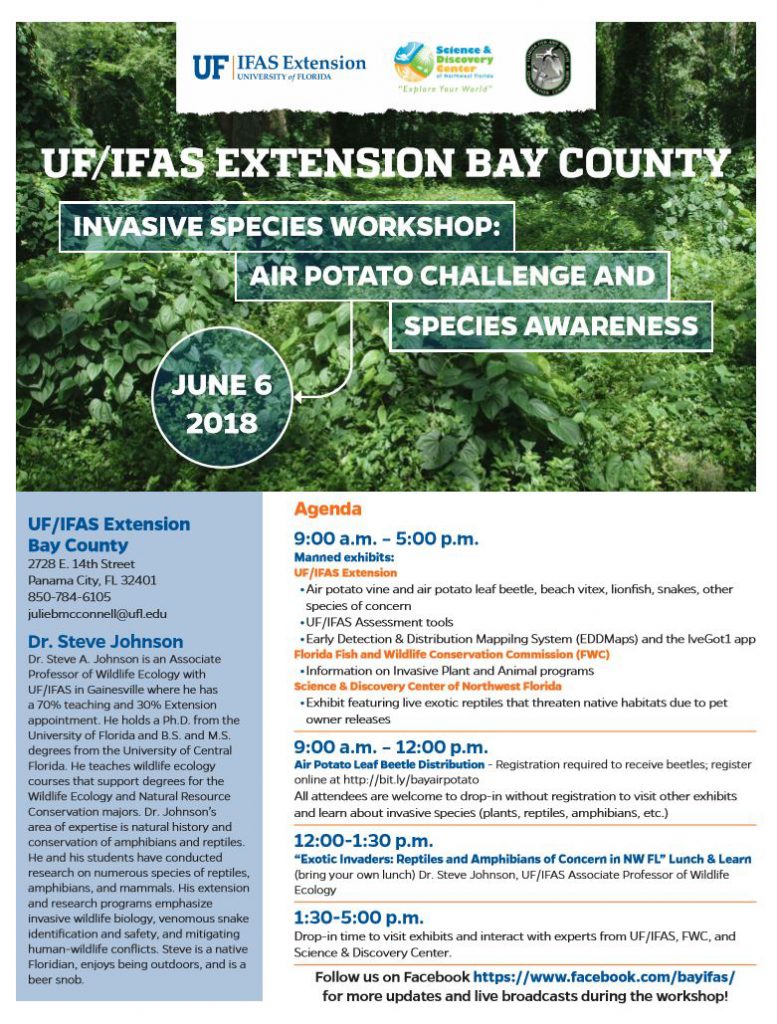

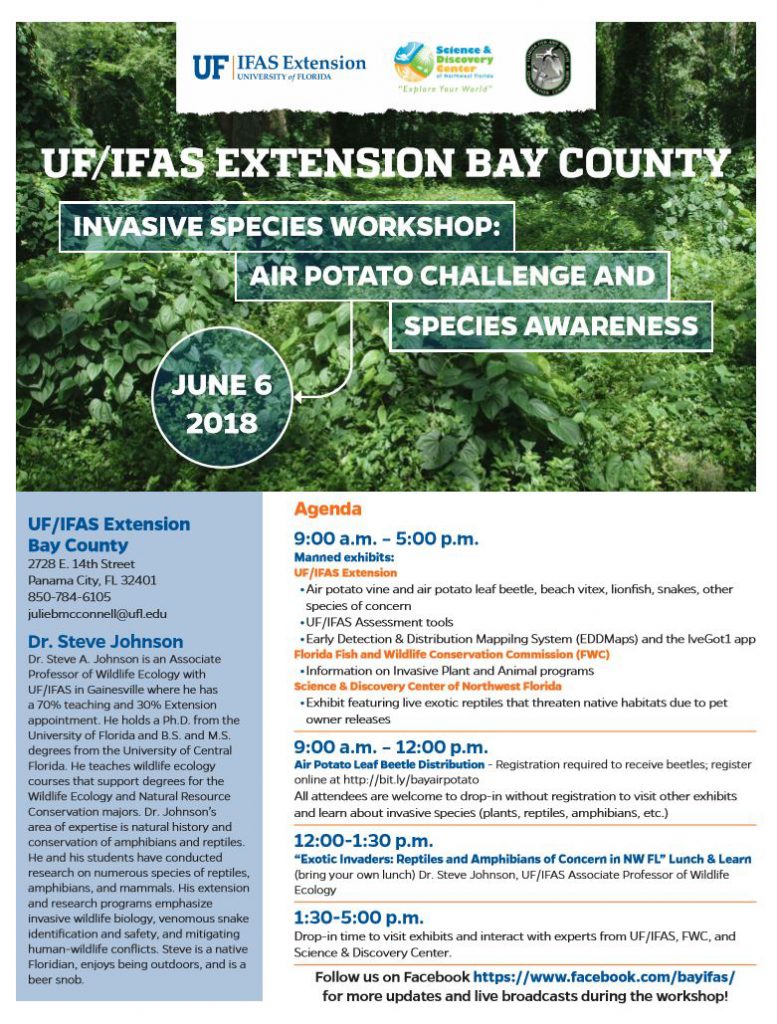

by Scott Jackson | May 25, 2018

By L. Scott Jackson and Julie B. McConnell, UF/IFAS Extension Bay County

Northwest Florida’s pristine natural world is being threaten by a group of non-native plants and animals known collectively as invasive species. Exotic invasive species originate from other continents and have adverse impacts on our native habitats and species. Many of these problem non-natives have nothing to keep them in check since there’s nothing that eats or preys on them in their “new world”. One of the most problematic and widespread invasive plants we have in our local area is air potato vine.

Air potato vine originated in Asia and Africa. It was brought to Florida in the early 1900s. People moved this plant with them using it for food and traditional medicine. However, raw forms of air potato are toxic and consumption is not recommended. This quick growing vine reproduces from tubers or “potatoes”. The potato drops from the vine and grows into the soil to start new vines. Air potato is especially a problem in disturbed areas like utility easements, which can provide easy entry into forests. Significant tree damage can occur in areas with heavy air potato infestation because vines can entirely cover large trees. Some sources report vine growth rates up to eight inches per day!

Air Potato vines covering native shrubs and trees in Bay County, Florida. (Photo by L. Scott Jackson)

Mechanical removal of vines and potatoes from the soil is one control method. Additionally, herbicides are often used to remediate areas dominated by air potato vine but this runs the risk of affecting non-target plants underneath the vine. A new tool for control was introduced to Florida in 2011, the air potato leaf beetle. Air potato beetle releases have been monitored and evaluated by United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) researchers and scientists for several years.

Air Potato Beetle crawling on leaf stem. Beetles eat leaves curtailing the growth and impact of air potato. (Photo by Julie B. McConnell)

Air potato beetles target only air potato leaves making them a perfect candidate for biological control. Biological controls aid in the management of target invasive species. Complete eradication is not expected, however suppression and reduced spread of air potato vine is realistic.

UF/IFAS Extension Bay County will host the Air Potato Challenge on June 6, 2018. Citizen scientist will receive air potato beetles and training regarding introduction of beetles into their private property infested with air potato vine. Pre-registration is recommended to receive the air potato beetles. Please visit http://bit.ly/bayairpotato

In conjunction with the Air Potato Challenge, UF/IFAS Extension Bay County will be hosting an invasive species awareness workshop. Dr. Steve Johnson, UF/IFAS Associate Professor of Wildlife Ecology, will be presenting “Exotic Invaders: Reptiles and Amphibians of Concern in Northwest Florida”. Additionally, experts from UF/IFAS Extension, Florida Fish and Wildlife, and the Science and Discovery center will have live exhibits featuring invasive reptiles, lionfish, and plants. For more information visit http://bay.ifas.ufl.edu or call the UF/IFAS Extension Bay County Office at 850-784-6105.

Flyer for Air Potato Challenge and Invasive Species Workshop June 6 2018

by Carrie Stevenson | Mar 2, 2018

Bamboo shoots. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson

Standing in the midst of a stand of bamboo, it’s easy to feel dwarfed. Smooth and sturdy, the hollow, sectioned woody shoots of this fascinating plant can tower as tall as 70 feet. Unfortunately, bamboo is a real threat to natural ecosystems, moving quickly through wooded areas, wetlands, and neighborhoods, taking out native species as it goes.

We do have one native species referred to as bamboo or cane (Arundinaria gigantea), which is found in reasonable numbers in southeastern wetlands and the banks of rivers. There are over a thousand species of true bamboo, but chief among the invasive varieties that give us trouble is Golden Bamboo (Phyllostachys aurea). Grown in its native Southeast Asia as a food source, building material, or for fishing rods, bamboo is also well known as the primary diet (99%) of the giant panda. In the United States, the plant was brought in as an ornamental—a fast growing vegetative screen that can also be used as flooring material or food. Clumping bamboos can be managed in a landscape, but the invasive, spreading bamboo will grow aggressively via roots and an extensive network of underground rhizomes that might extend more than 100 feet from their origin.

As a perennial grass, bamboo grows straight up, quickly, and can withstand occasional cutting and mowing without impacts to its overall health. However, a repeated program of intensive mowing, as often as you’d mow a lawn and over several years, will be needed to keep the plant under control. Small patches can be dug up, and there has been some success with containing the rhizomes by installing an underground “wall” of wood, plastic, or metal 18” into the soil around a section of bamboo.

Whimsy art Panda in a bamboo forest at the Glendale Nature Preserve. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson

While there are currently no chemical methods of control specifically labeled for bamboo at this time, the herbicides imazapyr (trade name Arsenal and others) or glyphosate (Round-up, Rodeo) applied at high rates can control it. According to research on the topic, “bamboo should be mowed or chopped and allowed to regrow to a height of approximately 3 feet, or until the leaves expand. Glyphosate at a 5% solution or imazapyr as a 1% solution can then be applied directly to the leaves.” These treatments will often need to be repeated as many as four times before succeeding in complete control of bamboo.

Land managers should know that while imazapyr is typically a more effective herbicide for bamboo, it can kill surrounding beneficial trees and shrubs due to its persistence in the contiguous roots and soil. In contrast, glyphosate solutions will only kill the species to which it has been applied and is the best choice for most areas managed by homeowners.

Bamboo Control: http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/AG/AG26600.pdf