by Rick O'Connor | Nov 13, 2020

This is not a word that most visitors to the beach want to hear. However, shark attacks are actually not that common and the risk is very low. People hear this every year on shark programs, but it does not seem to make them feel any better. Here is what the International Shark Attack File says (as of 2020)…

– Since the year 1580 there have been 3164 unprovoked shark attacks around the world.

Let that sink in for a moment… 3000 unprovoked attacks on humans in the last 440 years.

Now consider the number of car accident victims that have occurred in the last month within the United States. See what they are getting at? Let’s look at more…

– Of the 3164 reported unprovoked attacks (yes… these data only include what was reported) 1483 were from the United States… 47% of them. This may be due to the fact we are “water people”. The other top countries are Australia, South Africa, and Brazil, all “water people” as well.

– Of the 3164 reports 851 were from Florida (27%). This is the number of reported shark attacks in our state since the Spanish settled it. This comes out to 2 each year – though the data shows a sharp increase in attacks starting in the 1970s (most have occurred since then).

– Of the 3164 reports 25 were from the panhandle region (0.8%) and 7 from the Pensacola Bay area (0.2%).

Let that sink in for a moment. Seven reported attacks from the Pensacola Beach area since the time DeLuna landed here in 1559… 7.

And lets once again consider the number of vehicle accidents that will occur in the bay area today.

These numbers have been posted before. Yet people are still very worried when the hear sharks are in the Pensacola Beach region. When attacks occur, they are big news. The International Shark Attack File does give trends and suggestions on what to do. But as many say, sharks are the least of your worries when you are planning a day at the beach.

Now that we have said all of that, they are truly amazing animals.

They are fish but differ in that their skeletons lack hard calcified bone – they are cartilaginous. There are 25 species in 9 different families in the Gulf of Mexico. Many are completely harmless – 13 of the 25 have been reported to have had unprovoked attacks somewhere around the world – the white, tiger, and bull sharks leading the way. Several rarely come close to shore.

Sharks lack a swim bladder and thus cannot “float” in the water column the way your aquarium fish do. Some, like the nurse and angel sharks, rest on the bottom. Others, like the white and blue sharks, swim constantly to get water flowing over their gills.

Because of this, they are very streamlined with reduce scales. They actually have modified teeth for scales – called placoid scales. Their fins are angular and rigid (as are other open water fish) and some can swim quite fast – makos have been clocked at over 30 mph for short distances. Many have seen video of large white sharks exploding with a burst of speed on a sea lion and actually leaping out of the water with it.

Many species do lay eggs, but others keep the eggs within and give live birth after they hatch. One species, the sand tiger, produce four embryos within the mother. The first to hatch consumes the other three!

The teeth of sharks are famous. Rows of them, some pointed, some are serrated, all are designed to cut and swallow. The tiger shark has a serrated tooth that is angled like a can opener. They can use this to “open” sea turtle shells – adding them to their rather large menu. They “shed” these frequently – placing a new sharp tooth where the dull old one was – and will go through tens of thousands of teeth in a lifetime.

The sensory system is one of the most amazing in the world. Tiny gelatinous cells along their sides, called the lateral line, detect pressure waves from great distances. Splashing, thrashing movements made by fish can be detected a mile away – and get their attention. As they approach the sound their sense of smell kicks in. It has been said that a shark can detect one drop of blood in thousands of gallons of water – and it is true. However, the sharks must be down current of the victim to detect it. Their eyes are much better than most think. They have “crystals” within their retina that act as mirrors reflecting light that enters. Imagine turning on a flashlight in a dark room. Now imagine doing this if the walls and ceiling were mirrors – you kind of understand how they can actually see pretty well even in the low light. That said, light does not travel well under water, so they rely on their other senses more. And as if that were not enough. They have small gelatinous cells around the head region that can detect small electric fields. When a shark bites, it must close its eyes and – as the fishermen say – “roll back” out of the head. At this point the shark is basically blind and cannot see the target it is trying to bite. However, if you move out of the way, the weak electric fields produced by your muscles in doing so can be detected by these cells and the shark knows where you are.

Cool – and scary at the same time. Let’s meet a few of these amazing fish in our area.

https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/shark-attacks/

The nurse shark. Notice the barbels (whiskers) on its head.

Photo: NOAA

Nurse Shark

This is one of the bottom dwelling sharks that appear harmless – and they are – but if provoked, they will bite. They have less angular fins, or a brownish-bronze color, and really like structure – they are found on our reefs. They posses a “whisker-like” structure called a barbel. These are common on other bottom fish, like catfish, and possess chemo-sensory cells to detect prey buried in the sand. They are not as common here as they are in the Keys, but they have been seen. They can reach lengths of 14 feet.

Blacktip sharks are one of the smaller sharks in our area reaching a length of 59 inches. They are known to leap from the water. Photo: Florida Sea Grant

Blacktip – Spinner

These are grouped together because (a) they resemble each other, and (b) they are both common here.

They are both stream-lined in shape and have blacktips on their fins. Actually, spinner sharks have more fins tipped-black than the blacktip. The anal fin of the spinner is tipped black, but this is not the case for the blacktip. The spinner gets its name from the habit of leaping from the water and spinning very fast as it does so. Both are quite common in the Gulf and the bay. They reach about eight feet in length and unprovoked attacks are very rare.

The Scalloped Hammerhead is one of five species of hammerheads in the Gulf. It is commonly found in the bays. Photo: Florida Sea Grant

Hammerheads

This is a creepy group – check out the head. It is one that many people fear, and unprovoked attacks have occurred. The reader may not know that there are more than one kind – five species actually. They have a tall dorsal fin which sometimes extends above the water when swimming near the surface – the classic “shark is coming” look. Their heads are aerofoil shaped and there are several possible explanations for this. 1) It is more aerodynamic, making it easier for this ram-jetter to swim, using less energy to do so. 2) It is a battery of sensory cells. By swinging the head back and forth, as they do, it is an advanced radar searching for prey, possibly finding it before other sharks do. There are stories of hammerheads arriving first. 3) It is also believed they use their electric sense to detect buried prey – the shape making this easier to find and expose them. It could very well be that all of these could explain the shape.

This pregnant bull shark has an impressive girth.

Bull Shark

Since the film Jaws the world has turned its attention from solely the white shark – to the bull shark. As you can imagine, it is hard for a shark attack victim to tell you which species bit them – “I don’t know… it was a big gray thing chomping on my leg!” or “It was a great white!” because that is the only one many know. But studies sine the 1970s suggest that the bull shark is an aggressive species and may be responsible for a lot of attacks. Particularly in the estuaries and upper estuaries. Bull sharks are what we call euryhaline – they have tolerance for a wide range of salinities. This shark has been reported in low salinities of the upper estuaries and even into freshwater rivers. One report had them over 100 miles from the coast – they are certainly where the people are.

The extremely long upper lobe of the thresher shark.

Image: NOAA

Thresher Sharks

These are bizarre looking sharks. Most sharks have what we call a heterocercal tail – different – different meaning the upper lobe of the forked tail is longer than the lower. But the threshers take this to the extreme – the tail can make up almost half of their body length, which can be 20 feet. It is believed that use this extremely long tail to herd and stun baitfish – their favorite prey. They prefer colder waters and records in the Gulf are not common. Those that exist suggest they live offshore and are rarely encountered near beaches. There are no unprovoked attacks reported from this shark.

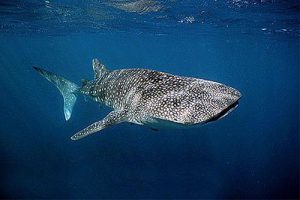

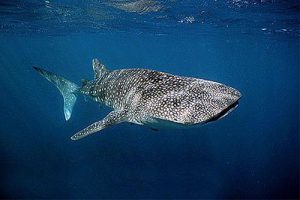

The massive whale shark.

Photo: Florida Museum of Natural History.

Whale Shark

Amazing… heart stopping… what else can you say. Encounters with the largest fish on our planet are rare – but when they do happen you will never forget it – it will be one of the highlights of your life. As the name suggest – these are large sharks, with a mean length of 45 feet but some reporting in at 60 feet. They are easily recognized first by their size, but also their coloration. They are brownish color with beige or white spots in nice rows running across the dorsal side. They swim slowly filtering plankton from the sea – though will occasionally take in a fish. Some reports show them vertical in the water column moving up and down filtering from a school of plankton or tiny fish. They are rarely seen because they tend to dive deeper during the day with the plankton layer – then surfacing at night following the same plankton. They are, unfortunately, sometimes struck by boats while at the surface.

by Sheila Dunning | Oct 16, 2020

That’s the question from a recent group exploring what washed up on the beach after Hurricane Sally.

Sea Cucumber

Photo by: Amy Leath

They have no eyes, nose or antenna. Yet, they move with tiny little legs and have openings on each end. Though scientists refer to them as sea cucumbers, they are obviously animals. Sea cucumbers get their name because of their overall body shape, but they are not vegetables.

There are over 1,200 species of sea cucumbers, ranging in size from ¾“ to more than 6‘ long, living throughout the world’s ocean bottoms. They are part of a larger animal group called echinoderms, which includes starfish, urchins and sand dollars. Echinoderms have five identical parts to their bodies. In the case of sea cucumber, they have 5 elongated body segments separated by tiny bones running from the tube feet at the mouth to the opening of the anus. These squishy invertebrates spend their entire life scavenging off the seafloor. Those tiny legs are actually tube feet that surround their mouth, directing algae, aquatic invertebrates, and waste particles found in the sand into their digestive tract. What goes in, must come out. That’s where it becomes interesting.

Sea cucumbers breathe by dilating their anal sphincter to allow water into the rectum, where specialized organs referred to as respiratory trees (or butt lungs) extract the oxygen from the water before discharging it back into the sea. Several commensal and symbiotic creatures (including a fish that lives in the anus, as well as crabs and shrimp on its skin) hang out on this end of the sea cucumber collecting any “leftovers”.

But, the ecosystem also benefits. Not only is excess organic matter being removed from the seafloor, but the water environment is being enriched. Sea cucumbers’ natural digestion process gives their feces a relatively high pH from the excretion of ammonia, protecting the water surrounding the sea cucumber habitats from ocean acidification and providing fertilizer that promotes coral growth. Also, the tiny bones within the sea cucumber form from the excretion of calcium carbonate, which is the primary ingredient in coral formation. The living and dying of sea cucumbers aids in the survival of coral beds.

When disturbed, sea cucumbers can expose their bony hook-like structures through their skin, making them more pickle than cucumber in appearance. Sea cucumbers can also use their digestive system to ward of predators. To confuse or harm predators, the sea cucumber propels its toxic internal organs from its body in the direction of the attacker. No worries though. They can grow them back again.

Hurricane Sally washed the sea cucumbers ashore so you could learn more about the creatures on the ocean floor. Continue to explore the Florida panhandle outdoor.

by Rick O'Connor | Sep 11, 2020

There is a lot of blue out there… a whole lot of blue. Miles of open water in the Gulf with nowhere to hide… except amongst yourselves. Their blue colored bodies, aerodynamically shaped like bullets with stiff angular fins, can zip along in this vast blue openness in large schools. Their myoglobin rich red muscle increases their swimming endurance – they can travel thousands of miles without tiring. Some species are what we call “ram-jetters”, fish that basically do not stop swimming – roaming the “big blue” looking for food and avoid being eaten, following the warm currents in search of their breeding grounds.

The open water is a place for specialists. Most of these fish have small, or no scales, to reduce frictional drag. They have a well-developed lateral line system so when a member of the school turns, the others sense it and turn in unison – just as the four planes in the US Navy Blue Angels delta do – perfect motion.

Many are built for speed. Sleek bodies with sharp angular fins and massive amounts of muscle / body mass, some species can reach speeds close to 70 mph – some can “fly”. There are fewer species who can live here, as opposed to the ocean floor, but those who do are amazing – and some of the most prized commercial and recreational fishing targets in the world. Let’s meet a few of them.

Flying fish do not actually “fly”, they are gliders using their long pectoral fins.

Photo: NOAA

Flying Fish

First, they do not actually fly – they glide. These tube-shaped speedy fish have elongated pectoral fins, reaching half the length of their bodies. The two lobes of their forked tail are not the same length – the lower lobe being longer. Using this like a rudder, they gain speed near the surface and, at some point, leap – extend the large pectoral fins, and glide above the water – sometimes up to 100 yards. As you might guess, this is to avoid the sleek speedy open water predators coming after them. You might also imagine that they, and their close cousins the half-beaks, are popular bait for the bill fishermen seeking those predators.

There are eight species of these amazing fish in the Gulf of Mexico ranging in size from 6-16 inches. Most are oceanic – never coming within 100 miles of the coast, but a few will, and can, be seen even near the pass into Pensacola Bay.

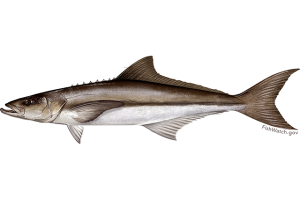

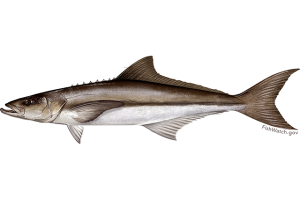

The cobia – also known as the ling, lemonfish, and sergeant fish, is a migratory species moving through our area in the spring.

Image: NOAA

Cobia

This is one of the migrating fish local anglers gear up for every year – the cobia run. When the water turns from 60° to 70°F in the spring – the cobia moves up the coastline heading from east to west. They have many different common names along the Gulf Coast. Ling, Cabio, Lemonfish, and Sergeant fish have all been used for this same animal. This is one reason biologists use scientific names – Rachycentron canadum in this case. That way we all know we are talking about the same fish. Whatever you call it, it is popular with the anglers and there is nothing like a fresh cobia sandwich – try one!

They can get quite large – 5 feet and up to 100 pounds – and resemble sharks in the water, sometimes confused with them. They seem to like drifting flotsam, where potential prey may hangout, and fishermen will toss their baits all around their schools trying to get them to take. At times, fishermen have confused sea turtles with cobia and have accidentally snagged them – only to release it, though it is a workout to do so, and they try to avoid it.

Cobia are in a family all their own. Their closest relatives are the remoras, or sharksuckers, which sometimes attach to them. They travel all over the Gulf and Atlantic Ocean.

Jacks have the sleek, fast design of the typical open water marine fish.

Photo: NOAA

Jacks

This is the largest open water family of fish I the northern Gulf – with 24 species. Not all jacks are open water, many are found on reefs and in estuaries. But these are aerodynamic shaped fish, with small scales and angular fins, and built for the open water environment. They vary in size, ranging from less than one foot, to over three. This group is identified by the two extended spines just in front of their anal fin. Several species – such as the amberjacks, pompano, and almaco jacks – are prized food fish. Others – like the jack crevalle and the blue runner (hardtail) – are just fun to catch, putting up great fights.

They are schooling fish and often associated with submerged wrecks and reefs, where prey can be found. The black and white pilot fish is called this because mariners would see them swimming in front of sharks – “piloting” them through the ocean. They are open water jacks but are more tropical and accounts in our area are rare.

The colors of the mahi-mahi are truly amazing.

Photo: National Wildlife Federation

Mahi–Mahi

This is the Hawaiian term for a fish called the dolphin (Coryphaena hippurus). You can probably guess why they prefer to call it by its Hawaiian name. It is a popular food fish, and to have “dolphin” on the menu – or to say “hey, we’re going dolphin fishing – want to come?” would raise eyebrows – and have.

The Mexicans call it “dorado”, and that term is used locally as well. Either name – it is an amazing fish. With the bull-shaped forehead of the males – they are sometimes referred to as the “bull-dolphin”. Their colors, and color changing, is amazing to see. Some biologists believe this may be some form of communication between members, don’t know, but the brilliant greens, blues, and yellows are amazing to see. They lose these colors shortly after death, so you must see it to believe it – or find one of the popular fish t-shirts.

Like jacks, dolphin like to hang around flotsam, or large schools of baitfish, looking for prey. As with many other open water predators, they will sometimes work in a team to scare, and scatter, individuals from the safety of their school. There are only two species in this family, and both are prized for their taste.

The Striped Mullet.

Image: LSU Extension

Mullet

This is not one you would typically call an “open water” fish. But in the nearshore Gulf and estuaries, they are more open water than bottom dwellers – though they do feed off the bottom. Sleek bodied, forked tail, angular fins, they have what it takes to be a fast swimmer. Though they do not “fly” as the flying fish do, they do leap out of the water. Many visitors hanging out around the Sound will hear a fish splash and immediately ask “what kind of fish was that?” Many locals will respond without looking up – “it was a mullet” – and they are probably right.

This brings up the age-old question… why do mullet jump? This was once asked of a marine biology professor. He paused… thought… and responded saying “for the same reasons manta rays jump”. That was it… another long pause. Finally, the students “took the bait” – “Okay, why do manta rays jump?”. The professor replied, “we don’t know”. So, there you go.

Another interesting thing about this fish is its wide tolerance of salinity. Mullet have been found in freshwater rivers and springs and the hypersaline lagoons of south Texas – they truly don’t care.

Locally they are popular food fish, and support a large commercial fishery in Florida, but in other parts of the Gulf not so much. It has to do with their environment and what they are feeding on. In muddier portions of the Gulf (or our bay for that matter) they have an oily taste and locals there call the “trash fish”. Even hearing that locals here eat them “grosses” them out. Local respond by giving it a more “high end” name – the Mulle (spoken with a French accent). This is actually the Cajun term for the fish. And let’s step it up a notch by adding that many locals eat mullet row – the eggs. Yea… getting hungry right? One of the popular cable food shows came here to try mullet roe. They said on a scale of 1 to 10, they give it a -4.

All that said, it is a local icon – with seafood stores selling “In Mullet We Trust” t-shirts, and the popular “Mullet Toss” event held every year on Perdido Key. It is a COOL fish.

This Spanish Mackerel has the distinct finlets of the mackerel family along the dorsal and ventral side of the body.

Image: NOAA

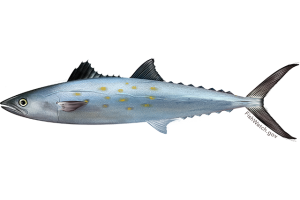

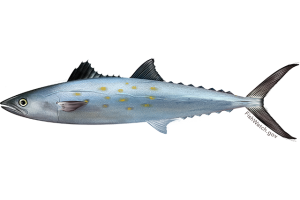

Mackerel

When you mention mackerel around here you usually think of one of two fish – the king mackerel (sometimes just referred to as “the king”) and the Spanish mackerel. But it is actually a large family of open water fish that includes the tuna, bonito, and the wahoo (of baseball fame).

They are some of the fastest fish in the sea, and several species are ram-jetters. Sleek bodies, sharp angular fins, they can be identified by the row of small finlets on the dorsal and ventral sides of their bodies near the rear. Full of red muscle, rich in myoglobin (which can hold more oxygen than hemoglobin alone), these are powerful swimming fish and very popular in the sushi trade. A bluefin tuna can be 14 feet long, 800 pounds, and bring a commercial fisherman tens of thousands of dollars. Because of this bluefin tuna are internationally protected and managed.

Another cool thing about these guys is that some species can control blood flow, and location, to help maintain a higher body temperature – “warm blooded” – allowing them to venture into colder waters of the world’s oceans. They are one of the big migratory fish we find. Following the large ocean currents, some species use this to play out their entire life cycle. Born in the warmer portions of the ocean gyres, they grow and feed in the cooler areas, returning in the warmer currents to breed.

There are 12 species in this family ranging in size from 1 to 15 feet. They have the characteristic “dark on top – light one bottom” coloration many animals have. This called countershading. It is believed to be used as a form of camouflage in the deep blue – with the darker blue-indigo on top (to blend in with the bottom if look from above) and the lighter silver-white on the bottom (to blend in with the sunlit surface if viewed from the below). This idea was used by the US Navy during World War II. If you visit our Naval Aviation Museum, you will see they painted the planes a darker blue on top and a lighter white on bottom. In hopes that the Japanese pilots would have a hard time spotting them over the Pacific Ocean. It is also believed to help with temperature control. The darker side will absorb heat, while the lighter side releases – avoiding over-heating. Amazing fish, aren’t they?

by Rick O'Connor | Sep 3, 2020

We continue our series on estuarine and marine fish and wildlife with fish who live on the bottom.

This longnose killifish has the rounded fins of a bottom dwelling fish.

The Gulf of Mexico is a huge ecosystem. With 600,000 m2 and an average depth of 6000 feet, there is a lot of “blue” out there for fish to find a home. But oddly enough, 69% of the species describe in the northern Gulf live on the bottom – what we call benthic fish.

This makes since really. In the “open blue” there are few places to hide from predators and prey. On the other hand, the seafloor has numerous places to hide – so there they are.

Most benthic fish have a general body design for living there. They are generally deep bodied, more rounded – as are their fins. They have a higher percentage of white muscle which makes them very explosive – for a few seconds. This is how they live. Blending in with the bottom, waiting for the prey to get within range and then exploding on it. This white muscle also gives these fish a distinctive taste, different from the red muscle typically found in the open water fish such as tuna.

In this environment, the sense of smell is very good. Many have taste and smell buds extended on fleshy appendages called barbels (the “whiskers” of a catfish). Many will have their mouth on the bottom side of their head for easier eating – though the predators (like the grouper) will still have it directly in front. Many will make short migrations into estuaries for breeding, but long open ocean migrations are not common. There are 342 species of benthic fish in the northern Gulf, let’s look at a few.

The Anguilla eel, also known as the “American” and “European” eel.

Photo: Wikipedia.

Eels

Something about these animals creeps us out. Maybe their similarity to snakes? Maybe the thought they are electric or venomous – neither of which are true. There are electric eels in the Amazon, but not in the ocean. They do behave much like snakes in that they have very sharp teeth for grabbing prey and can use them on fishermen if they need to. There are 16 species of eels in the northern Gulf. With the exception of the morays – eels live in sandy or muddy bottoms. Shrimpers frequently haul them up, and some are even known as shrimp eels. The American eel (Anguilla rostrata) has a cool life history. They spawn in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, a place known to the sailors as the Sargasso Sea. It is in the middle of the vortex of ocean currents. The young that catch the northern currents and head to Europe – there they are known as the “European Eel”. Those that catch the southern swirl end up here in the United States are known as the “American Eel”. Their young look like thin pieces of plastic with eyes. Known as elvers they can be found within Pensacola Bay by the thousands when they arrive. The growing adults move up stream and spend part of their lives in our rivers and springs, before swimming back to the Atlantic and starting the process all over. In some areas, there is a commercial fishery for this eel.

Read more:

https://fws.gov/fisheries/freshwater-fish-of-america/american_eel.html.

https://www.fws.gov/fisheries/fishmigration/american_eel.html.

The serrated spines and large barbels of the sea catfish. Image: Louisiana Sea Grant

Catfish

This is a bottom fish that fishermen love to hate. Marine catfish (Ariopsis felis) are oily and not as popular as their freshwater cousins as food. So, when fishermen catch them, they tend to toss them on the beach to die – the idea is that there are fewer to breed – an idea that really does not work – they keep catching them. One interesting twist on this story is that the ghost crabs in the dunes drag the dead ones towards their burrows where they feed on them. The skull of the sea catfish is very hard – giving them their other common name “hardhead” catfish, or “steelhead”. When the crabs are finished the hard skull can be found and the bones on the belly (ventral) side resemble the cross. It is sold in some novelty stores as the “crucifix fish”. To add to the legend, when you shake it, it rattles. This has been described at the “soldiers rolling dice” at the crucifixion. They are actually loose bones. These “crucifix fish” are pretty neat, and pretty common.

The long “whiskers” (barbels) are for finding food buried beneath the sand or mud. It is also believed they may have a form of echolocation to detect prey. As if this were not interesting enough – the males carry the developing eggs within their mouths. Development takes about two weeks and young fish emerge from dad ready for the world.

One other thing the visitor should know – the serrated spine on the dorsal and the pectoral fins can inflict a nasty wound, even releasing a mild toxin. Most discover this when they step on a dead one tossed on the beach, or trying to get one off their hook – be careful of this.

Read more:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hardhead_catfish.

http://gcrl.usm.edu/public/fish/hardhead.catfish.php.

https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/269847.

The classic look of a bottom fish. This is the redfish, or red drum.

Photo: NOAA

Drum–Croaker

This is the largest family of estuarine fish in the northern Gulf of Mexico – with 18 species described. The whiting, drum, kingfish, croakers, trout, some perch, and others all belong to this group. They are popular with fishermen and seafood consumers. The red drum (redfish) is one of the more popular targets in our area. Speckled trout (or spotted seatrout) are also a favorite. Most have the characteristic body of a benthic fish. Deep bodied, rounded fins, mouth on the belly (ventral) side. Sea trout have two large “Dracula” looking fangs for grabbing shrimp and other prey. In most, one has broken off and the angler usually finds only one fang present. Some species, such as the black drum, will have short “whiskers” on their chins – you guessed it, barbels – and they are used for finding “buried treasure” (food).

Their common name drum (or croaker) comes from the sounds they produce using their swim bladders. Swim bladders are large sacs within many fish they can fill with gas and float off the bottom. The drum-croaker group rub this with internal muscles making resonating sounds that sound like they are “croaking”. Atlantic bottlenose dolphin can hear this too – and croakers make up a big part of their diet.

Read more:

http://gcrl.usm.edu/public/fish/red.drum.php.

http://gcrl.usm.edu/public/fish/spotted.seatrout.php.

http://gcrl.usm.edu/public/fish/southern.kingfish.php

http://gcrl.usm.edu/public/fish/sand.seatrout.php

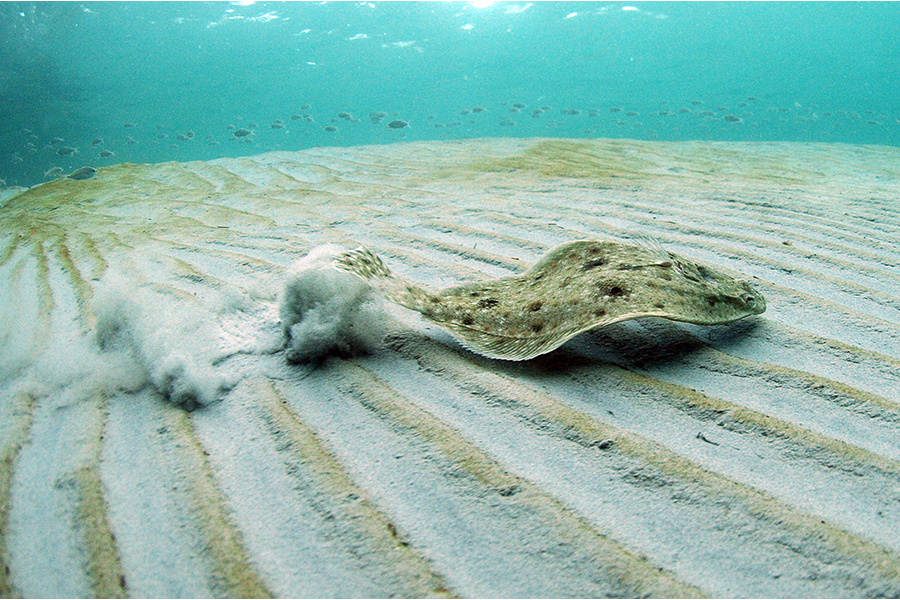

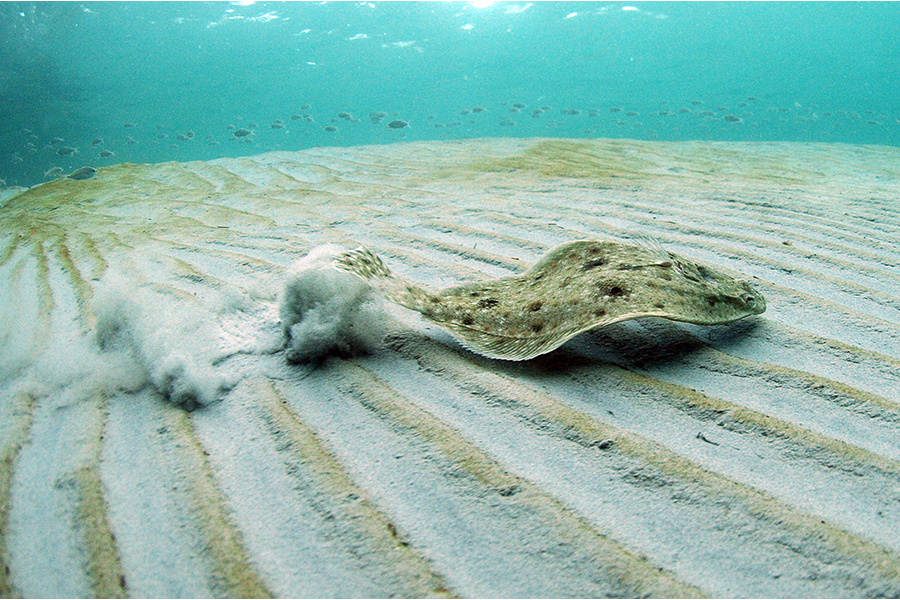

A flounder scurrying across the seafloor.

Photo: NOAA

Flounder

There are actually two types of flatfish in the Gulf – the flounder and the sole. How do you tell them apart?

Well, they are born as a typical-normal looking fish, but as they grow one eye begins to “slide” across the top of the head to the other side – both eyes are now on one side of the head – weird right?

In our part of the Gulf, if the eyes slide to the left side – we call it a flounder, to the right – a sole. There are a FEW exceptions to this rule – but many call the popular flounder the “left-eyed flounder” as opposed to the “right-eyed” one.

So why do they do this?

If your eyes were placed on each side of a torpedo pointed head, you would have what we call monocular vision. This type of vision gives you ALMOST 360° range of view… almost. So even though you can see what is behind you while facing forward, you do not have good depth perception – so you are not sure exactly how far away it is. You must either rely on other senses to help you out or get lucky. Having both eyes on one side (or in front like us) you have binocular vision. You cannot see behind you, but you can tell the distance of the object in front of you. This is common for predator fish like flounder. Many would agree that your mother has both!

With the eyes on one side of the head, they lose color on the other and then lay flat on one side. They can bury in sand and wait for prey. Most species have chromatophores in their skin. These are cells that allow them to change color, like a chameleon or octopus. So, they can change their color to blend into whatever bottom type they are on. What an incredible adaptation.

There are 17 species of flounder, and they are not easy to tell apart – so just call them flounder.

Read more:

http://gcrl.usm.edu/public/fish/flounder.php.

by Rick O'Connor | Aug 13, 2020

Mammals are historically land-based, or terrestrial, animals. They are quadrupeds (four legs) and run with a cursorial form of locomotion (backbone moving up and down) – some are the fastest land animals the planet has ever seen. But as fate would have it, some returned to the sea and occupied niches there. They are so well designed for a life in water that even look like fish. However, they differ in several ways:

1) Their tail extends horizontally instead of vertically and moves in an up and down motion instead of a side to side.

2) They of course lack scales, but they lack the characteristic hair of mammals as well. Though some hair may be found if you look close enough, they use blubber (layers of fat) to keep their bodies warm instead. Due to their warm blooded-ness, many do very well in cold parts of the ocean.

3) They also have mammalian lungs – not gills. Amazingly they exchange almost 90% of the air in their lungs with each breath (compared to about 20% for humans). With this huge load of oxygen, they remain underwater for long periods of time and dive to deep depths. The record would belong to the sperm whale who can dive to depths of 3000 feet for up to 90 minutes!

4) And of course, they give live birth nurturing the developing fetus with a placenta and feeding the developing young with milk from their mammary glands – this is not found in fish.

There are three orders of marine mammals: The Cetaceans (whales and dolphins), Pinnipeds (seals and sea lions), and Sirenians (manatees and dugongs). All three were once found in the Gulf of Mexico. Today there are only cetaceans and sirens, the lone pinniped (the Caribbean Monk Seal) is now believed to be extinct.

A group of small dolphin leap from the ocean.

Photo: NOAA

Dolphins

The Atlantic Bottlenose Dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) is the most common dolphin seen by visitors in our area. This lively, playful, and intelligent creature is the one most often seen at aquarium shows. Dolphins are whales, just small ones, and belong to a group known as “toothed whales”. They have numerous conical canine-type teeth used for grabbing fish and squid. Lacking molars, they cannot chew – so they must select prey they can either cut into smaller pieces, or swallow whole as is.

The toothed whales are known for their ability to detect prey using a form of SONAR called echolocation. Sound pulses are produced by flaps of skin within the blowhole (the nostrils of the dolphin) and exit the animal through a blob of fat in the head called the melon. Low frequency clicks can travel farther and find the targets, high frequency clicks have smaller range but can tell the dolphin what type of fish it is, and some whales can even produce high enough frequencies to literally “stun” their prey in the water – making it easier to grab. These “echo’s” or “clicks” are usually above (or below) our hearing range.

Dolphins are very social animals, traveling in large groups called pods. The pods are typically made of adult females and young, though there are one or two males. They communicate with each other using sound. The sounds are produced from the larynx in the blowhole area and are distinct for each pod. Outside dolphins are usually not allowed within the pod, so dolphins are not always the friendly creatures we perceive them to be – at least to each other.

When mom gives birth to a single calf (though very rare, twins have occurred) she rolls while swimming forward to expel the young – who must quickly surface for it’s first breath. The other females in the pod usually help with this. The baby suckles milk from hidden mammary glands which the mom exposes with the calf nudges her side. The calves stay with their moms for about two years learning the tricks of the trade before the cycle begins again.

These are truly amazing animals. Read more about dolphins at:

https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/species/common-bottlenose-dolphin.

https://www.dolphincommunicationproject.org/index.php/the-latest-buzz/the-dolphin-pod/item/94419-how-does-echolocation-work.

The large head and double blowhole of a Bryde’s whale.

Photo: NOAA

Whales

Though dolphins are whales, there are many others. The order Cetacea is broken into two suborders – the toothed whales (Odontoceti – which includes the dolphins) and the baleen whales (Mysteiceti). There are at least 20 species of whales and dolphins reported from the Gulf of Mexico – only one of those is a baleen whale, the Bryde’s Whale. Mammals as a group are known as heterodonts (meaning they have more than one type of tooth in their mouths). You, for example, have incisors, canines, pre-molars, and molars. Whales and dolphins break this rule by being homodonts. The toothed-whales and dolphins have conical canine teeth. Baleen whales have a fibrous hair-like material in their upper jaw that is stiff like the bristles of a toothbrush called baleen. The whale swallows seawater and then pushes it through the baleen trapping small shrimp and fish which they lick down their throats.

Whales are known for their long migrations – some of the longest in the animal kingdom. Their thick blubber and large size allow them to survive in polar waters – where much of their food is found. However, their babies are smaller (albeit 5-10 feet small) and they are not prepared for such cold waters. So, mom must migrate to tropical waters to give birth – fatten the baby up with some of the richest milk in the mammal group – and migrate back so she can feed herself. To navigate they use sound, the Earth’s magnetic field, and their eyes to do so. Whales can produce very low frequency sounds that can travel thousands of miles across the ocean echoing off objects that may be familiar to them. They also have magnetite in their retinas that allow them to pick up the Earth’s magnetic field, much the same as a compass does. And scientists also believe the act of spyhopping, where a whale will stop – turn vertical in the water – and extend their head above the surface – is in fact checking landmarks to aid them.

As with dolphins – these are amazing animals. Read more at:

https://aquatic.vetmed.ufl.edu/services/stranding-response/marine-animals-of-the-gulf-of-mexico/.

https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/species/brydes-whale.

http://www.pbs.org/kqed/oceanadventures/episodes/whales/indepth-navigation.html.

Manatee swimming in Big Lagoon near Pensacola.

Photo: Marsha Stanton

Manatees

“Mermaids”… at least that was what Christopher Columbus thought when he reached the new world. I guess they have that body shape… I guess. These are marine mammals but are not related to whales and dolphins. Instead, their closest living relatives are elephants. This is because mammals are divided into orders based on the type, and number, of teeth they have – and manatee teeth are nothing like dolphins. They have square shaped molars with ridges on the upper surface for grinding plant material – they are vegetarians. Most herbivores, like horses, have large incisors that can cut the grass and then move them back to their gnawing molars. Manatees lack these incisors. Instead they use their large lips, much the same as an elephant uses its trunk, to extend – and grab the grass, pulling it from the bottom of the bay and then gnawing with those big molars.

The differ from dolphins in other ways:

1) Their fluke (tail) is more round than forked – and they travel MUCH slower.

2) They lack a blow hole – but do still have nostrils. They are positioned closer to where ours are so they must extend part of their head out of the water in order to breath.

3) Though some whales lack dorsal fins – all manatees do.

4) They also do not tolerate polar waters very well. There was one species – the Stellar Sea Cow – that lived in Alaska, but this animal was MUCH larger than the tropical manatee – large size allows you to maintain a higher body temperature. It is now extinct – hunted out by fishermen as a food source while fishing. The animal was actually named after one of them – Captain Georg Stellar.

5) They are also not as social – manatees are usually loners except during breeding season and gathering in warm springs during the winter.

That said, they are migrators as well. They will venture out during the warm months to seagrass beds in the north – including Pensacola Beach – returning to the warm springs of central Florida, or the tropical waters of south Florida, in the winter. Navigation, in their case, is a bit easier – they are coastal – manatees do not travel out to sea as whales and dolphins do. They slide along the coastline, eating as they go, enjoying the sun, and avoiding boats. Locally we see them along the Gulf side, in the Intracoastal, and even up into the bays and bayous of Pensacola Bay as they move from Mobile Bay to and from central Florida.

WE DO HAVE A CITIZEN SCIENCE REPORTING PROGRAM FOR THIS ANIMAL.

If you see one contact Sea Grant Agent Rick O’Connor (roc1@ufl.edu ). We would like to know – exactly where you saw it, date you saw it, time you saw it, was it alone, and which direction was it traveling.

As with other marine mammals – manatees are amazing to see and can be the highlight of your visit. We ask that while boating, when you approach shore please slow speed and (if possible) have a spotter looking to make sure you do not hit one of these charismatic creatures.

Read more at:

https://www.fws.gov/refuge/Crystal_River/wildlife_and_habitat/Florida_Manatee.html.

https://www.savethemanatee.org/manatees/migration/.

by Rick O'Connor | Jul 7, 2020

For many of the blogs we have posted on marine life of the Gulf of Mexico I have used the term “amazing” – but these cephalopods are truly amazing. There have been numerous nature programs featuring not just marine invertebrates but rather highlighting the cephalopods specifically. We have been amazed by their looks, their colors, their intelligence, and their ferocity. They are the animals of ancient mariner legends – the “kraken”.

These are not your typical mollusk. The elongated body and lack of external shell changes everything for cephalopods.

Photo: California Sea Grant

But for us who just visit the beach to play and walk – we rarely see them. They are quite common. The squid are almost transparent in the water column as they swim and usually run deep until nighttime. The only ones I have ever encountered were hauled up in shrimp trawls – but they are usually hauled up each time, and sometimes in great numbers. Octopus are more nighttime roamers as well. I have occasionally seen them diving during daylight hours, but they are very secretive and well camouflaged. I have found cephalopods both in the Gulf and within the estuaries – again, they are more common than we think.

A study conducted in the 1950s logged 42 species within the Gulf of Mexico. Many of them live in the open sea and at depths of 350-500 feet. There are actually four types of cephalopods – the octopus and squid we know, the cuttlefish and nautilus less so because they are not common in the Gulf region.

They are mollusk but differ from their snail and clam cousins in that they have very little, if any shell. The nautilus is an ancient member of this group and still possess an external shell. However, it is chambered and can be filled with gas like a hot air balloon allowing the nautilus to hover off the seafloor – something their snail/clam cousins can only dream about.

The squid and cuttlefish have reduced their shell to a surfboard looking structure that is found internally, serving almost like backbone. It allows them some rigidity in the water column, and they can grow to greater size. Actually, the squid are the largest invertebrates on the planet, with the “giant squid” (Architeuthus) reaching lengths of 50 feet or more.

The octopus differs from the squid in that it lacks a shell all together. Thus, it is smaller and lives on the ocean floor.

Photo: University of South Florida

The octopus lack a shell all together. Without this rigid bone within, they cannot reach the great size of the giant squid – so giant octopus are legend. However, there is a large one that grows in the Pacific that has reached lengths of 30 feet and over 500 pounds – big enough!

The lack of a shell means they must defend themselves in other ways. One is speed. With no heavy shell holding you down, high speed can be achieved. Again, squid are some of the fastest invertebrates in the ocean – being clocked at 16 mph. This may not outrun some of the faster fish and marine mammals, and many fall victim to them. Birds are known to dive down and eat large numbers of them. But they can counter this by having chromatophores. These are cells within the skin filled with colored pigments that they can control using muscles. This allows them to change color and hide. And their ability to change color is unmatched in the animal kingdom. I recommend you find some video online of the color change (particularly of the cuttlefish) and you will be amazed. Yes… amazed.

The chromatophores allow the cephalopods to change colors and patterns to blend in.

Photo: California Sea Grant

To control such color, they must have a more developed brain than their snail/clam cousins – and they do. The large brain encircles their esophagus and not only be used to ascertain the colors of the environment (and how to blend in) but also has the capability of learning and memory. The octopus in particular has been able to solves some basic problems – to escape, or get food from a closed jar, for example. Many of these chromatophores possess iridocytes – cells that act has mirrors and enhance the colors – again, amazing to watch.

All cephalopods are carnivorous and hunt their prey using their well-developed vision. Squid prefer fish and pelagic shrimp. Octopus are inclined to grab crustaceans and other mollusk – though they will grab a fish when the opportunity presents itself. Cephalopods hunt with their tentacles – which are at the “head end” of the body. The squid possess eight smaller arms and two longer tentacles. Each have a series of sucker cups and hooks to grab the prey. They keep their tentacles close to their bodies and, when within range, quickly extend them grabbing the fish and bringing back to the mouth where a sharp parrot-like beak is found. They bite chunks of flesh off and some have seen them bite the head off a mackerel. I was bitten on the hand by a squid once – one of the more painful bites I have ever had.

The extended tentacles of this squid can be seen in this image.

Photo: NOAA

The octopus does not have the two long tentacles – rather only the eight arms (hence its name). They move with stealth and camouflage (thanks to the chromatophores) sneaking up on their prey – or lying in wait for it to come close. Here things change a bit. Octopus possess a neurotoxin similar to the one found in puffer fish. They can bite the crab – inject the venom – which includes digestive enzymes similar to rattlesnakes and spiders – and ingest the body of the semi-digested prey after it dies. They can drill holes into mollusk shells and inject the venom within. Most will give a painful bite but there is one in the Indo-Pacific (the blue-ringed octopus) whose venom is potent enough to kill humans.

Making new octopus and squids involves the production of eggs. The male will deposit a sac of sperm called a spermatophore into the body of the female. She will then fertilize her eggs and excrete them in finger like projections that do not have hard shells. Squid usually die afterwards. Octopus will remain with the eggs – oxygenating and protecting them until they hatch. At which time they will die.

Though we have a variety of cephalopods near shore – the real grandeur is offshore. Out there are numerous species of bioluminescent cephalopods – most living at 500 feet during the day and coming within 300 feet at night. Many swim, while some float, others have developed a type of buoyant case they can carry their eggs in. Far too much to go into in a blog such as this one. I recommend you do a little searching and learn more about these amazing animals.

Enjoy the Gulf!