by Rick O'Connor | Jun 26, 2020

This is a good name for this group. They are mollusk that have two shells. They tried “univalve” with the snails and slugs, but that never caught on – gastropods it is for them. The bivalves are an interesting, and successful, group. They have taken the shell for protection idea to the limit – they are COMPLETELY covered with shell. No predators… no way. But they do have predators – we will talk more on that.

An assortment of bivalves, mostly bay scallop.

Photo: Florida Department of Environmental Protection.

As you might expect, with the increase in shell there is a decrease in locomotion – as a matter of fact, many species do not move at all (they are sessile). But in a sense, they do not care. They are completely covered and protected. Again, we will talk more about how well that works.

The two shells (valves) are connected on the dorsal side of the animal and hinged together by a ligament. Their bodies are laterally compressed to fit into a shell that is aerodynamic for burrowing through soft muds and sands. Their “heads” are greatly reduced (even missing in some) but they do have a sensory system. Along the edge of the mantle chemoreceptive cells (smell and taste) can be found and many have small ocelli, which can detect light. The scallops take it a step further by having actually eyes – but they do live on the surface and they do move around – so they are needed.

The shells are hinged together at the umbo with “teeth like structures and the shells open and close using a pair of adductor muscles. Many shells found on the beach will have “scars” which are the point of contact for these muscles. They range is size from the small seed clams (2mm – 0.08”) to the giant clam of the Indo-Pacific (1m – 3.4 ft) and 2500 lbs.! Most Gulf bivalves are more modest in size.

Being slow burrowing benthic animals, sand and mud can become a problem when feeding and breathing. In response, many bivalves have developed modified gills to help remove this debris, and many actually remove organic particles using it as a source of food. Many others will fuse their mantle to the shell not allowing sediment to enter. But some still does and, if not removed, will be covered by a layer of nacreous material forming pearls. All bivalves can produce pearls. Only those with large amounts of nacreous material produce commercially valuable ones.

Coquina are a common burrowing clam found along our beaches.

Photo: Flickr

Another feature is the large foot, used for digging a burrowing in the more primitive forms. It is the foot we eat when we eat clams. They can turn their bodies towards the substrate, begin digging with their foot but also using their excurrent from breathing to form a sort of jet to help move and loosen the sand as they go – very similar to the way we set pilings for piers and bridges today.

These are the earliest forms of bivalves – the burrowers. Most are known as clams and most live where the sediment is soft. Located near their foot is a sense organ called a statocyst that lets them know their orientation in the environment. Most have their mantles fused to their shells so sand cannot enter the empty spaces in the body. To channel water to the gills, they have developed tubes called siphons which act as snorkels. Most burrow only a few inches, some burrow very deep and they are even more streamlined and elongated.

Some have evolved to burrow into harder material such as coral or wood. One of the more common ones is an animal called a shipworm. Called this by mariners because of the tunnels they dig throughout the hulls of wooden ships, they are not worms but a type of clam that have learned to burrow through the wood consuming the sawdust of their actions. They have very reduced shells and a very long foot.

This cluster of green mussels occupies space that could be occupied by bivavles like osyters.

Other bivalves secrete a fibrous thread from their foot that is used to grab, hold, and sometimes pull the animal along. These are called byssal threads. Many will secrete hundreds of these, allow them to “tan” or dry, reduce their foot, and now are attached by these threads. The most famous of this group are the mussels. Mussels are a popular seafood product and are grown commercial having them attach to ropes hanging in the water.

Another method of attachment is to literally cement your self to the bottom. Those bivalves who do this will usually lay on their side when they first settle out from their larval stage and attach using a fluid produced by the animal. This fluid eventually cements them to the bottom and the shell attached is usually longer than the other side, which is facing the environment. The most famous of these are the oysters. Oysters basically have lost both their “head” and the foot found in other bivalves. These sessile bivalves are very dependent on tides and currents to help clear waste and mud from their bodies.

Oysters are a VERY popular seafood product along the Gulf coast.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Then there are the bivalves who actually live on the bottom – not attached – and are able to move, or even swim. Most of these have well developed tentacles and ocelli to detect danger in the environment and some, like the scallops, can actually “clap their shells together” to create a jet current and swim. This is usually done when they detect danger, such as a starfish, and they have been known to swim up to three feet. Some will use this jet as a means of digging a depression in the sand they can settle in. In this group, the adductor has been reduced from two (the number usually found in bivalves) to one, and the foot is completely gone.

As you might guess, reproduction is external in this group. Most have male and female members but some species (such as scallops and shipworms) are hermaphroditic. The gametes are released externally at the same time in an event called a mass spawning. To trigger when this should happen, the bivalves pay attention to water temperature, tides, and pheromones released by the opposite sex or by the release of the gametes themselves.

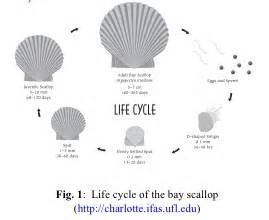

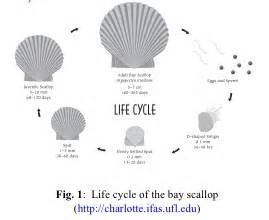

Scallop life cycle.

Image: University of Florida IFAS

The fertilized eggs quickly develop into a planktonic larva known as a veliger. This veliger is ciliated and can swim with the current to find a suitable settling spot. Some species have long lived veliger stages. Oysters are such and the dispersal of their veliger can travel as far as 800 miles! Once the larval stage ends, they settle as “spat” (baby shelled bivalves) on the substrate and begin their lives. Some species (such as scallop) only live for a year or two. Others can live up to 10 years.

As a group, bivalves are filter feeders, filtering organic particles and phytoplankton as small as 1 micron (1/1,000,000-m… VERY small). In doing this they do an excellent job of increasing water clarity which benefits many other creatures in the community. As a matter of fact, many could not survive without this “eco-service” and the loss of bivalves has triggered the loss of both habitat and species in the Gulf region. Restoration efforts (particularly with oysters) is as much for the enhancement of the environment and diversity as it is for the commercial value of the oyster.

Now… predators… yes, they have many. Though they have completely covered their bodies with shell, there are many animals that have learned to “get in there”. Starfish and octopus are famous for their abilities to open tightly closed shells. Rays, some fish, and some turtles and birds have modified teeth (or bills) to crush the shell or cut the adductor muscle. Sea otters have learned the trick to crush them with rocks and some local shorebirds will drop them on roads and cars trying to access them. And then there are humans. We steam them to open the shell and cut their adductor muscle to reach the sweet meat inside.

It is a fascinating group – and a commercial valuable one as well. Lots of bivalves are consumed in some form or fashion worldwide. Take some time at the beach to collect their shells as enjoy the great diversity and design within this group. EMBRACE THE GULF!

by Rick O'Connor | Jun 11, 2020

One of the largest groups of invertebrates in the Gulf are the Mollusk… what many call “seashells”. Shell collecting has been popular for centuries and, in times past, there were large shows where shells from around the world were traded. Almost everyone who visits the beach is attracted to, and must take home, a seashell to remind them of the peace beaches give us. Many are absolutely beautiful, and you wonder how such small simple creatures can create such beauty.

One of the more beautiful shells from the sea – the nautilus.

Photo: Wikipedia

Well, first – not all mollusk are small. There are cephalopods that rival the size of some sharks and even whales.

Second, many are not that simple either. Some cephalopods are quite intelligent and have shown they can solve problems to reach their food.

But beautiful they are, and the colors and shapes are controlled by their DNA. Just amazing.

There are possibly as many as 150,000 different species of mollusks. These species are divided into 8-9 classes (depending which book you read) but for this series on Embracing the Gulf we will focus on only three. First up – the snails (Class Gastropoda).

There are an estimated 60,000 – 80,000 species of gastropods, second only to the insects. They are typically called snails and slugs and are different in that they produce a single coiled shell. The shell is made of calcium carbonate (limestone) and is excreted from tissue called the mantle. It covers their body and continues to grow as they do. The shell coils around a linear piece of shell called the columella. Most coil to the right, but some to the left – sort of like right and left-handed people. There is an opening in the shell where the snail can extend much of its body – this is called the aperture – and some species can close this off with a bony plate called an operculum when they are inside. Some snail shells have a thin extension near the head that protects the siphon – a tube that acts like a snorkel drawing water in and out of the body.

The black siphon can be seen in this crown conch crawling across the sand.

Photo: Franklin County Extension.

They have pretty good eyes and excellent sense of smell. They possess antenna, which can be tactile or sense chemicals in the water (smelling) to help provide information to a simple brain.

They are slow – everyone knowns this – but they really don’t care. Their thick calcium carbonate shells protect them from most predators in the sea… but not all.

Their cousins the slugs either lack the shell completely, or they have a remnant of it internally. You would think “what is the point of an internal shell?” – good question. But the slugs have another defense – they are poisonous. Venomous and poisonous are two different things. Being poisonous means you have a form of toxin within your body tissue. If a predator eats you – they will get very sick, maybe die. But you die as well, so… Not too worry, poisonous slugs are brightly colored – a universally understood signal to all predators.

There is one venomous snail – the cone snail, of which we have about five species in the Gulf. They possess a stylet at the tip of their siphon (similar to the worms we have been writing about) which they can use as a dart for prey such as fish. Many gastropods are carnivores, but some are herbivores, and some are scavengers.

Many shells are found on the beach as fragments. Here you see the fragment of a Florida Fighting Conch.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Most have separate sexes and exchange gametes in a sack called a spermatophore. Fertilized eggs are often encased in structures that resemble clusters, or chains, of plastic. These are deposited on the seafloor and the young are born with their shell ready for life.

This group is not as popular as a food item as other mollusk but there are some. The Queen Conch is probably of the most famous of the edible snails, and escargot are typically land snails. I am not aware of any edible slugs… and that is good thing.

Some of the more common snails you will find along our portion of the Gulf of Mexico are:

Crown Conch Olive Murex Banded Tulip

Whelks Cowries Bonnets Cerith

Slippers Moon Oyster Drills Bubble

The most encountered slug is the sea hare.

A common sea slug found along panhandle beaches – the sea hare.

I hope you get a chance to do some shelling – I hope you find some complete ones. It is addictive!

by Carrie Stevenson | May 22, 2020

Sea pork comes in a wide variety of shapes and sizes. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Recently I was walking the beach, enjoying a sunset and looking around at the shells and other oddities in the wrack line where waves deposit their floating treasures. Something bright green and oblong caught my eye. It was emerald in color, smooth yet fuzzy at the same time, and firm to the touch. At first, I thought it was a sea bean–a collective term for the many species of seeds and fruits that float to our shores from tropical locations in the Caribbean or Central/South America. The bright green definitely seemed like something botanical in nature. However, the vast majority of sea beans have a woody, protective shell similar to our more familiar pecans or acorns.

I remembered a family member asking about finding a mystery chunk of pink mass she found on the beach a few years ago. It resembled a pork chop more than anything else.

A different variety of sea pork that really lives up to its name. Photo credit: Stephanie Stevenson, Duval County Master Gardener

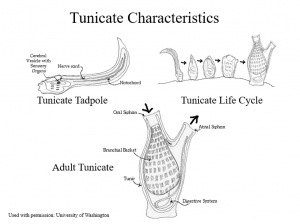

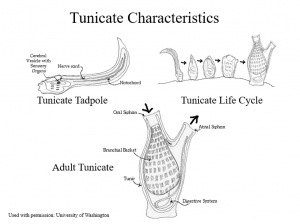

Looking closer and consulting a couple of resources, I realized we had both (most likely!) happened upon one of the oddest and often-questioned finds on our beaches: sea pork. Ranging in color from beige and pale pink to red or green, sea pork is a tunicate (or sea squirt), a member of the Phylum Chordata, home to all the vertebrate and semi-vertebrate animals. While they look and feel more like a cross between invertebrate slugs or sponges, the tunicates are more advanced organisms, possessing a primitive backbone in their larval “tadpole” form. Despite their blob-like appearance, they are more closely related to vertebrate animals than they are to corals or sponges.

The unusual life cycle of the tunicate. Photo credit: University of Washington, used with permission with Florida Master Naturalist program

During their short (just hours-long) larval stage, the tunicate larvae uses its nerve cord (supported by a notochord similar to a vertebrate spine) to communicate with a cerebral vesicle, which works like a brain. Similar to fish, this primitive brain uses an otolith to orient itself in the water, and an eyespot to detect light. These brain-like tools are utilized to locate an appropriate location to settle permanently. Using a sticky substance, the tunicate will attach its head directly to a hard surface (rocks, boats, docks, etc.) and go through a metamorphosis of sorts. The tunicate reabsorbs its tail and starts forming the shape and structure it needs for adulthood.

As an adult, the organism has a barrel shape covered by a tough tunic-like skin (hence “tunicate”). Adult bodies have two siphons, one to bring water in, another to shoot it out (giving them their other nickname, the sea squirt). The water passes through an atrium with organs that allow it to filter feed, trapping plankton and oxygen. The tunicates will spend most of their lives attached to a surface, pumping water in and out as filter feeders. They may be solitary or live in colonies, and vary widely in color and shape, lending variety to those chunks of sea pork found washing up.

I am still awaiting positive identification from an expert on my green find to confirm that it is, indeed, a tunicate and not an unfamiliar plant. Consulting with Extension colleagues, for now we are pretty confidently going with green sea pork. If you have seen one of these before or something resembling sea pork, let us know! It is fascinating to see the variety and unusual shapes and colors.

.

by Rick O'Connor | May 14, 2020

As we embrace the marine life of the Gulf of Mexico during this year of “Embracing the Gulf”, we are currently hooked on worms. In the last article we talked about the gross and creepy flatworms. Gross because they are flat, pale in color, only have a mouth so they have to go to the bathroom using it – and creepy in that many of them are parasites, living in the bodies over vertebrates (particularly fish) and that is just creepy. You may ask why would we even “embrace” such a thing? Well… because they do exist and most of us know nothing about them.

A nemertean worm.

Photo: Okinawa Institute of Science

This week we continue with worms. We continue with a different kind of flatworm. They are not as gross, but maybe a little creepy. They are called nemertean worms and I am pretty sure (a) you have never heard of them, and (b) you have never seen one. So why “embrace” these? Well… again it is education. They do exist, and one day you MAY see one – and know what you are looking at.

Nemerteans are flatworms. They are usually pale in color but a different from the classis fluke or tapeworm in a couple of ways.

1) They do have a way for food to enter and another for waste to leave, what we call a complete digestive tract – and that’s nice.

2) They have this long extension connected to their head called a proboscis. Many of them have a dart at the end they can use to kill their prey – and that’s creepy.

3) And as mentioned, most are carnivores, feeding on small invertebrates – and that’s okay.

We rarely see them because they are nocturnal – hiding under rocks, shells, seaweed during the day and hunting at night. Most are about eight inches long but some in the Pacific reach almost eight feet!

I would put that in the creepy file.

As we said, they are usually pale in color, though some may have yellow, orange, red, or even green hues to them. Their heads are spade shaped and, again, hold a retracted proboscis. This proboscis can be over half the length of the worm. At the end is a stylet (a dart) which they can use to stab their prey (small invertebrates). They can stab repeatedly, like using a knife, – they may stab and grab, like using a claw – or they may be a species that has toxin and kills their prey that way.

Nice.

Some would add this to the creepy file as well. A long pale worm, moving at night, extending a long proboscis when they get near you with a sharp dart at the end they essentially “sting” you like a bee.

Yea, creepy.

But we NEVER hear about such things with humans. They hunt small invertebrates like amphipods, isopods, and things like that. If you picked one up, would it stick the dart in you? My hunch would be yes – I honestly don’t know, I have only seen one to two in the 35+ years I have been teaching marine science and I did not pick them up. I have never met anyone who has and have never read “DON’T PICK THESE UP – VERY DANGERSOUS”. So, my hunch is that it would not be very painful at all.

But don’t take my word for it – again, I have rarely seen one… so, don’t pick them up 😊

There are about 650 species of nemertean worms in the world, 22 live in the Gulf of Mexico, and 16 live in the northern Gulf (near us). They are basically marine, move across the environment on their slime trails, seeking prey primarily by the sense of smell at night. Unlike the flukes and tapeworms, there are male and females in this group. They fertilize their eggs externally to make the next generation of these harpooning hunters of the Gulf.

I don’t know if you will ever come across one of these. You will know it by the flat body, pale color, and spade-shaped head, but I think it would be pretty neat to find one. There are more worms to learn about in the Gulf of Mexico, but we will do that in another edition.

by Rick O'Connor | Apr 17, 2020

I’d like to be a jellyfish… cause jellyfish don’t pay rent…

They don’t walk and they don’t talk with some Euro-trash accent…

Their just simple protoplasm… clear as cellophane

They ride the winds of fortune… life without a brain

These lyrics from Jimmy Buffett’s song Mental Floss sort of sums it up doesn’t it. The easy-going lifestyle of the jellyfish.

Everyone who visits the Gulf coast knows about these guys, but few people… very few… like them. For most, the term jellyfish signals “pain”, “fear”, and “death”. The purple flag is flying, and no one wants to enter the water. Folks from the Midwest call local hotels and condos asking, “when are the jellyfish going to be there?” It’s understandable. Who wants to spend their week vacation on the Gulf inside a hotel because you can’t go swimming?

I found this along the shore last winter. These are cannonball jellyfish.

I would almost (…almost) rather be diving with a shark than hundreds of jellyfish. When you spot them, they are everywhere. Quietly swarming like ghosts. You push them off and they appear to move towards you – almost like smoke from a campfire, you can’t get away.

They are creepy things. But amazing too!

As Mr. Buffett’s points out, they are simple “protoplasm”. Their body is primarily a jelly-like substance called mesoglea – and most of that is water. If you place a dead jellyfish on your dock and come back that afternoon, you will probably find just a “stain” of where it was – there is almost nothing to them.

The “bell” of the jellyfish is mostly mesoglea. Some jellyfish have thick layers of this, others much thinner. Some have a small flap of skin along the margins of the bell called the velum which they can undulate and swim – but they are not strong swimmers. If the tide is going out, swim as they may… their heading out also.

The bell shaped body of a jellyfish with numerous tentacles.

Many species of jellyfish have interesting markings within the bell. One has a white-colored structure that forms a 4-leaf clover. Another has red triangles all connecting at the center of the bell. For many, these structures are the ones that produce the gametes. Jellyfish reproduce sexually but are hermaphroditic – meaning they produce female eggs and male sperm in the same animal. There is no physical contact between animals, they just release the gametes into the ocean when they are in thick swarms and wah-la… new jellyfish – many new jellyfish.

On the bottom of the bell is a single opening that leads to a single pouch. This opening is the mouth, and the pouch is called the gastrovascular cavity. Jellyfish are predators – carnivores. There are no teeth, and most do not seek their prey – their prey finds them. Hanging from their bell are the tools of the killing trade, the part of this animal we do not like… the tentacles. Some tentacles can extend for several feet beyond the bell, others you can hardly notice them – but this is where the killing happens.

Along the tentacles there are small capsules called cnidoblasts which contain small cells called nematocyst. These nematocyst contain a coiled dart which at the end contains a drop of venom. There is a trigger associated with this cell. The jellyfish does not fire it – instead, the prey bumps the trigger and the nematocyst “fires”. The drop of venom is injected, along with the hundreds of other nematocysts along the tentacle the fish just bumped. This venom paralyzes the prey, other tentacles coil around it firing more nematocysts, and the tentacles retract towards the mouth – bingo… lunch.

This box jellyfish was found near NAS Pensacola in November of 2015.

Photo: Brad Peterman

Of course, the same happens when people bump into them. For us it is painful and unpleasant – but we are not consumed. That said, some species are quite painful. Some will force people to the hospital, and some have even killed people. The Box Jellyfish is the most notorious of these deadly ones. Known for their habits in Australia, there are at least two species found in the Gulf. The ones found here are not common, and there are no reported deaths, but they do exist. The Four-Handed is the one more widespread here. It actually has eyes, can detect predators and prey and swim towards or away from them, and the male fertilizes the female internally – not your typical jellyfish.

The more familiar painful one is the Portuguese Man-of-War. This creature is more like a sponge in that it is not just one creature but a large “condo” of many. Some cells are specialized in feeding, these are found on their long tentacles. Others specialize in reproduction; these are found near the blue colored air bag. They produce this blueish colored air bag which is exposed above the surface. The wind pushes on the bag like a sail and this moves the creature across the environment in search of food. Hanging from the bag are long tentacles which are made up of individuals whose stomachs are all connected. So, when one group of cells makes contact and kills a prey – they consume it and the tissue is moved through the connecting stomachs to feed the whole colony. To feed a whole colony, you need a big fish – to kill a big fish, you need a strong toxin, and they have it. These are VERY painful and have put people in the hospital, some have died. Some say that the Portuguese man-of-war is not a “true” jellyfish. This is true in the sense that they belong to a different class of jellyfish. There are three classes, the Scyphozoans being what we call the “true” jellyfish – Portuguese man-of-wars are not scyphozoans, but rather hydrozoans.

The colonial Portuguese man-of-war.

Photo: NOAA

Another interesting thing about jellyfish, is that they are all not jellyfish-like. As we just mentioned, there are two other classes and one other phylum of jellyfish-like animals. Hydrozoans and anthozoans are not your typical jellyfish. Rather than being bell-shaped and drifting in the ocean looking for food, they are attached to the seafloor and look more like flowers. Their tentacles are usually smaller but do contain nematocysts. Their toxin can be strong, some do eat fish, but most have a weaker toxin and feed on very small creatures – some only eat plankton. These would include the hydra, sea anemones, and the corals. As mentioned above, this also would include the Portuguese man-of-war.

Comb jellies are those jellies that drift in the currents and have no tentacles. We commonly collect them and toss them at each other. When I was growing up, we referred to them as “football jellies” because of this. The reason they do not sting is not because they do not have tentacles (some species do) but rather they do not have nematocyst and cannot. Rather they have special cells called colloblast that produce a drop of sticky glue at the end which they use to capture prey. Not having toxins, they cannot kill large prey but rather feed on smaller creatures like plankton and each other – they are cannibals. For this reason, they are in a whole different phylum.

The nonvenmous comb jelly.

Photo: Bryan Fluech

The jellyfish of the Gulf are a nuisance at times but are actually amazing creatures.

by Rick O'Connor | Feb 13, 2020

An eastern cottonmouth basking near a creek in a swampy area of Florida.

Photo: Tommy Carter

When you think of reptiles you typically think of tropical rainforest or the desert. However, there is at least one member of the three orders of reptiles that do live in the sea. Saltwater crocodiles are found in the Indo-Pacific region as are about 50 species of sea snakes. There is one marine lizard, the marine iguana of the Galapagos Islands, and then the marine (or sea) turtles. These are found worldwide and are the only true marine reptiles found in the Gulf of Mexico.

Sea turtles are very charismatic animals and beloved by many. Five of the seven species are found in the Gulf. These include the Loggerhead, which is the most common, the Green, the Hawksbill, the Leatherback, and the rarest of all – the Kemp’s Ridley.

Many in our area are very familiar with the nesting behavior of these long-ranged animals. They do have strong site fidelity and navigate across the Gulf, or from more afar, to their nesting beaches – many here in the Pensacola Beach area. The males and females court and mate just offshore in early spring. The females then approach the beach after dark to lay about 100 eggs in a deep hole. She then returns the to the Gulf never to see her offspring. Many females will lay more than one clutch in a season.

The largest of the sea turtles, the leatherback.

Photo: Dr. Andrew Colman

The eggs incubate for 60-70 days and their temperature determines whether they will be male or female, warmer eggs become females. The hatchlings hatch beneath the sand and begin to dig out. If they detect problems, such as warm sand (we believe meaning daylight hours) or vibrations (we believe meaning predators) they will remain suspended until those potential threats are no more. The “run” (all hatchlings at once) usually occurs under the cover of darkness to avoid predators. The hatchlings scramble towards the Gulf finding their way by light reflecting off the water. Ghost crabs, fox, raccoon, and other predators take almost 90% of them, and the 10% who do reach the Gulf still have predatory birds and fish to deal with. Those who make it past this gauntlet head for the Sargassum weed offshore to begin their lives.

These are large animals, some reaching 1000 pounds, but most are in the 300-400 pound range, and long lived, some reaching 100 years. It takes many years to become sexually mature and typically long-lived / low reproductive animals are targets for population issues when disasters or threats arise. Many creatures eat the small hatchings, but there are few predators on the large reproducing adults. However, in recent years humans have played a role in the decline of the adult population and all five species are now listed as either threatened or endangered and are protected in the U.S. There are a couple of local ordinances developed to adhere to federal law requiring protection. One is the turtle friendly lighting ordinance, which is enforced during nesting season (May 1 – Oct 31), and the Leave No Trace ordinance requiring all chairs, tents, etc. to be removed from the beach during the evening hours. There are other things that locals can do to help protect these animals such as: fill in holes dug on the beach during the day, discard trash and plastic in proper receptacles, avoid snagging with fishing line and (if so) properly remove, and watch when boating offshore to avoid collisions.

If we include the barrier islands there are more coastal reptiles beyond the sea turtles. There are freshwater ponds which can harbor a variety of freshwater turtles. I have personally seen cooters, sliders, and even a snapping turtle on Pensacola Beach. Many coastal islands harbor the terrestrial gopher tortoise and wooded areas could harbor the box turtles. In the salt marsh you may find the only brackish water turtle in the U.S., the diamondback terrapin. These turtles do nest on our beaches and are unique to see. Freshwater turtle reproductive cycles are very similar to sea turtles, albeit most nest during daylight hours.

An American Alligator basking on shore.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

The American alligator can also be found in freshwater ponds, and even swimming in saltwater. They can reach lengths of 12 feet, though there are records of 15 footers. These animals actually do not like encounters with humans and will do their best to avoid us. Problems begin when they are fed and loose that fear. I have witnessed locals in Louisiana feeding alligators, but it is a felony in Florida. Males will “bello” in the spring to attract females and ward off competing males. Females will lay eggs in a nest made of vegetation near the shoreline and guard these, and the hatchlings, during and after birth. They can be dangerous at this time and people should avoid getting near.

We have several native species of lizards that call the islands home. The six-lined race runners and the green anole to name two. However, non-native and invasive lizards are on the increase. It is believed there are actually more non-native and invasive lizards in Florida than native ones. The Argentina Tegu and the Cuban Anole are both problems and the Brown Anole is now established in Gulf Breeze, East Hill, and Perdido Key – probably other locations as well. Growing up I routinely find the horned lizard in our area. I was not aware then they were non-native, but by the 1970s you could only find them on our barrier islands, and today sightings are rare.

An eastern cottonmouth crossing a beach.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

Then there are the snakes.

Like all reptiles, snakes like dry xeric environments like barrier islands. We have 46 species in the state of Florida, and many can be found near the coast. Though we have no sea snakes in the Gulf, all of our coastal snakes are excellent swimmers and have been seen swimming to the barrier islands. Of most concern to residents are the venomous ones. There are six venomous snakes in our area and four of them can be found on barrier islands. These include the Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake, the Pygmy Rattlesnake, the Eastern Coral Snake, and the Eastern Cottonmouth. There has been a recent surge in cottonmouth encounters on islands and this could be due to more people with more development causing more encounters, or there may be an increase in their populations. Cottonmouths are more common in wet areas and usually want to be near freshwater. Current surveys are trying to determine how frequently encounters do occur.

Not everyone agrees, but I think reptiles are fascinating animals and a unique part of the Gulf biosphere. We hope others will appreciate them more and learn to live with and enjoy them.