by Rick O'Connor | Mar 14, 2025

If green algae are difficult to find in the northern Gulf because most prefer freshwater, and rocky shorelines, brown are difficult because the group prefers colder water, as well as rocky shorelines – but we do have some here.

Brown algae get their color because the ratio of photosynthetic pigments in their cells favors the xanthophylls – which produces a yellow-brown color. Like most macroscopic algae, they attach to the hard bottom using a holdfast and then extend their stipe and blade into the water column to absorb light. One group of brown algae are the largest of all seaweeds, the giant kelp Macrocystis. In the nutrient rich waters off California this seaweed will grow up to one foot a day and can reach heights of up to 175 feet tall. Since seaweeds do not possess true stems, or any wood, what holds this giant seaweed up are air filled bladders called pneumatocysts – structures found on other brown algae and are unique to the group.

The largest, fastest growing seaweed – giant kelp.

Photo: NOAA

Many species are popular with seafood dishes, such as Nori. Others produce a carbohydrate known as algin that is extracted and used as a food additive. You may have heard “ice cream has seaweed in it”. What it actually has is algin. This carbohydrate acts as a smoothing agent for products. Solids should be solid – like frozen ice cream – but, as you know, we do not want our ice cream solid. So, for a period of time, the algin keeps the ice cream smooth and creamy. Algin is used in toothpaste, lipstick, and icing on cakes for the same reason.

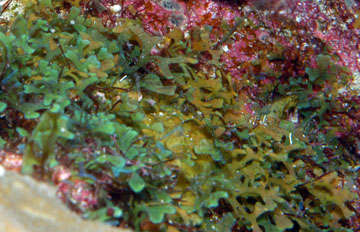

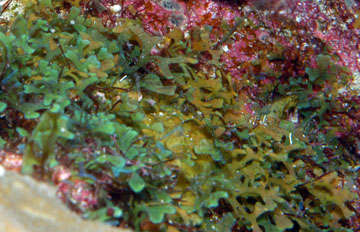

But along the northern Gulf coast, brown algae are not common. Despite preferring marine waters, they do prefer colder water and, like most seaweeds, need a hard substrate to attach their holdfast. But by exploring our local rock jetties and seawalls we do find some. One in particular is the common rock weed – Dictyota. This sessile seaweed branches out and resembles small trees. But the most common, and most recognized brown algae on our coast is Sargassum.

The brown algae Dictyota.

Photo: NOAA

Sargassum has found a way to deal with an environment where little hard bottom is present. Using the characteristic air bladders allows it to float at the surface to absorb the much needed sunlight. Because of this ability to float, Sargassum can be found all across the oceans, and often form large mats that cover miles of open sea and extend several feet down. It actually creates a whole new ecosystem in the middle of the sea. The major ocean currents rotate like a hurricane and, like a hurricane, the center – the “eye” – is calm. Within this calm huge mats of Sargassum collect. The ancient sailors called the center of the Atlantic Ocean the “Sargasso Sea”. But as the large currents spin, sections of this large mat “spin off” and are pushed across the ocean. Much of it heads towards Florida, the Gulf, and eventually to the northern Gulf.

If you grab a mask and snorkel and swim within the Sargassum before it reaches the waves, you will encounter a whole community of creatures that live here. Sargassum crabs, Sargassum fish, and even seahorses live within it. There are shrimps, worms, and even mollusks. When baby sea turtles head offshore after hatching, many seek out these Sargassum mats to both hide in, and feed within. They will spend their youth here before returning back to shore for different prey.

However, once many of these creatures sense the waves breaking, and now the mat is about to wash ashore, they will move to mats further offshore. That said, picking through the Sargassum on the beach may still yield some interesting creatures.

Sargassum.

In recent years the amount of Sargassum washing ashore has increased and become problematic – particularly in southeast Florida and the Florida Keys. At times, mounds three feet high have been found. Those communities are working on methods to deal with the problem. But here locally, these mats are a new world to explore.

References

Giant Kelp. Monterey Bay Aquarium. https://www.montereybayaquarium.org/animals/animals-a-to-z/giant-kelp.

by Rick O'Connor | Feb 21, 2025

They say life began in the oceans. We know that the lithosphere is cracked, adding new land, subducting land over time. But much of the lithosphere is covered with water – and here life began. Initially it had to begin on either rock or sand. The sand would have been produced by the weathering and erosion of rock. Obviously, this would all have had to occur over a long period of time. But the first forms of life would have to be able to find food and nutrition from a barren seafloor with little to offer. This would take a special community of creatures – ones we call the pioneer community.

It is believed that life began in the ocean.

Phot: Rick O’Connor

Key members of these communities would have been the producers’ ones who produce food. What we know now is that producers absorb carbon dioxide and water and – using the sun as a source of energy – convert this into carbohydrates and oxygen. We have since learned that there are ancient forms of bacteria that can do this with hydrogen sulfide and other compounds. However, it started – it began. One problem with this model is that much of the world’s oceans are too deep for sunlight to reach. Thus, living organisms would need to be close to shore. Today we know two things. One, the ocean’s surface is covered with microscopic plant-like creatures (phytoplankton) who can float and reach the sunlight. Two, some of the ancient chemosynthetic bacteria (those that do not need the sun and can use other compounds to produce carbohydrates) live on the ocean floor.

The black smokers – hydrothermal vents – found on the ocean floor.

Photo: Woodshole Oceanographic Institute.

Producers are followed by consumers, creatures who cannot make their own food and must feed on either the producers or on other consumers. There are plankton feeding animals – oysters, sponges, corals, and zooplankton. There are larger creatures that feed on larger plankton – manta rays, menhaden, and whales. There are consumers who feed on the first order of consumers – stingrays, parrotfish, and pinfish. And there are the top predators – orcas, sharks, and tuna. The ocean is a giant food web of creatures feeding on creatures. All creatures evolve defenses to avoid predation. Predators evolve answers to these defenses. Some species survive for long periods of time like the horseshoe crabs and nautilus. Others cannot compete and go extinct.

Horseshoe crabs are one of the ancient creatures from our seas. Photo: Bob Pitts

As we mentioned in Part 1 of this series – the hydrosphere is in motion. Different temperatures, pressure, and the rotation of the planet move water all over. These currents bring food and nutrients, remove waste, and help disperse species across the seas. Life spreads to other locations. Some conditions are good – and life thrives. Others not so much – and only specialists can make it. The biodiversity of our oceans is an amazing. Coral reefs, mangrove forests, and seagrass beds are home to thousands of species all interacting with each other in some way. The polar regions are harsh – but many species have evolved to live here, and the diversity is surprising higher than most think. The bottom of the sea is basically unknown. It has been said we know more about the surface of the moon than we do at the bottom of our ocean. But we know there is a whole world going on down there. We believe the basic principles of life function there as they do at the surface – but maybe not!

The magical lights of the deep sea.

Photo: NOAA

Fossil records suggest life here began almost one billion years ago. The fossils they find are of creatures similar and different from those inhabiting our ocean currently. As we stated that the physical planet is under constant change – life is as well. It is a system that has been working well for a very long time. Over the last few centuries humans have studied the physical and living oceans to better understand how these systems function. They have been functioning well for a very long time. And though life began at sea – there was dry land to exploit – for those who could make the trip. That will be next.

by Rick O'Connor | Dec 20, 2024

In our last article we asked the question – “what are protozoans?” As we mentioned then the breakdown of the word includes “proto” which means “before”, and “zoan” which refers to animals. These are the “before animals” – meaning animal-like creatures BEFORE there were true animals.

They are single celled creatures that lack a cell wall and chlorophyll – animal-like – but they are only single celled – so, not true animals. Being animal-like means they cannot produce their own food as the diatoms, dinoflagellates, seaweeds, and true plants do. Rather, they must consume food as animals do. Some feed on diatoms and dinoflagellates. Some feed on decaying organic matter on the seafloor. Some are parasitic and feed off of a host organism. Some feed on other protozoans. And some do a combination. But they are all consumers.

The group is classified into six phyla mostly based on how they move. One subphylum is the Sarcodinids – which move using blobby extensions of their cytoplasm called pseudopods. Under a microscope they would resemble a fried egg oozing across the slide. They are NOT fast. They can use these pseudopods not only for moving but for gathering food. I remember watching them under a scope in college. They slowly oozed across the slide engulfing most other protozoans and phytoplankton they encountered. They were like the “sharks” of the micro-world. Many live on the seafloor, or within the sediments themselves. Some are parasites. And there are a few planktonic forms. Their primary role in the marine system is moving energy through the food chain and cleaning up the environment. As with the flagellates, there two common groups in marine waters – the foraminiferans and the radiolarians.

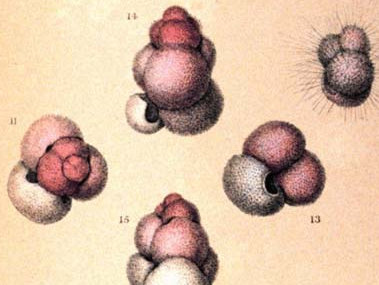

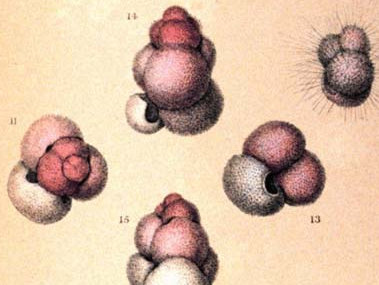

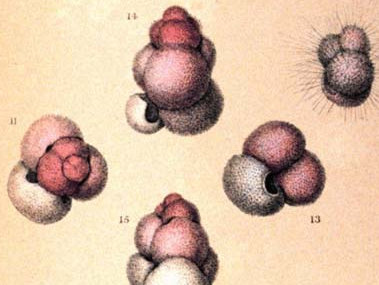

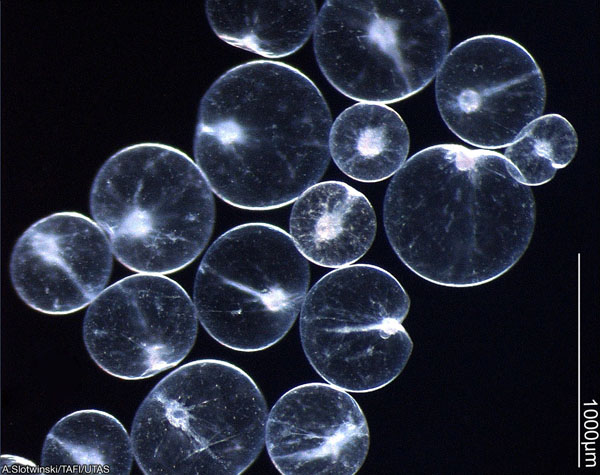

The first true oceanographic research cruise was the voyage of the HMS Challenger in 1872. The chief scientist on this first expedition was Charles Wyville Thomson, a marine geologist and one very interested in what was on the ocean floor. During the first leg of the voyage – from Europe to the America’s – they collected sediment samples several time each day. By far most of the ocean floor was made of what was called “globigerina ooze”. Globigerinids are a group of marine foraminiferans. They produce a calcium carbonate shell that is chambered. Under a microscope they look very much like seashells. They are part of the plankton layers in the ocean – what would be called “zooplankton”. Many possess spines on their shells to help reduce sinking. When they die their shells fall to the seafloor. Over time they formed the thick layers of sediment Thomson witnessed and called “ooze”. He also discovered that most of the ocean floor is covered with these microscopic shells. The Gulf of Mexico is no different. Most formaminiferans live on the seafloor and contribute to the sediment layers from there. One group forms mats on rocks that look pink in color and are responsible for the pink sands found in Bermuda.

Artist image of Globigerina.

Image: NOAA

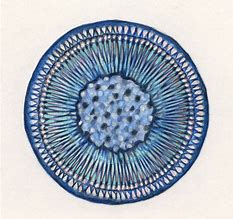

Another group of shelled amoeboid protozoans are the radiolarians. Under the microscope these are some of the most beautiful creatures you will find in the northern Gulf. Like diatoms, their shells are made of silica and look like glass. Most have spines and shapes that make them resemble snowflakes – truly beautiful. Like foraminiferans, when they die their shells settle on the seafloor and contribute to the ooze layers. Radiolarian ooze has been found as deep as 12,000 feet.

The snowflake-like shells of radiolarians.

Image: Wikipedia.

These small, microscopic amoeba like animals play an important role in moving food and energy through the Gulf. Their discovery on the seafloor helped marine geologists better understand how our oceans formed and how they have changed over time. On other beaches around the world, they have contributed to sands giving some beaches very unique colors – which are popular with tourists. They are an unknown, but important part of the marine community in the northern Gulf of Mexico.

References

Yaeger, R.G. 1996. Protozoa: Structure, Classification, Growth, and Development. Chapter 77. Medical Microbiology, 4th edition. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK8325/#A4082.

by Erik Lovestrand | Nov 22, 2024

In early November a local crabber, Kevin Martina, brought an interesting catch to the Franklin County Extension office in Apalachicola. Kevin and his brother Kenneth Martina fish for blue crabs in Apalachicola Bay and they came across what appeared at first glance to be a red-colored blue crab. In all their combined years of working crab pots, neither of them had seen a crab like this. On closer inspection at the Extension Office, there appeared to be some differences from a blue crab, other than the striking red coloration. It was the innate curiosity of our Extension Office Manager, Michelle Huber, that led us to the discovery that the crab was a species with a native range spanning Jamaica and Belize to Santa Caterina, Brazil. After Michelle showed photos of what she had found on her phone, we reached out to colleagues at the Apalachicola National Estuarine Research Reserve (ANERR) and told them we might have a Bocourt swimming crab (Callinectes bocourti). I told them that I could find no range maps indicating this species lived in our region. The nearest US Geological Survey data points for the species in the Gulf of Mexico were Alabama to the West and the Florida Everglades to the South. It was not long after the ANERR staff reached out to the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission that we received interest in confirming the identification and officially documenting the Bocourt swimming crab find.

Bocourt Swimming Crab – USGS/South Carolina DNR

The first documented occurrence of a Bocourt swimming crab in the US happened in 1950 in South Florida. Since then, there have been rare finds in AL and MS and more common occurrences from South Florida all the way up to North Carolina on the Atlantic Coast. Theories about how they arrived include possible transport of larvae in ships’ ballast water or a natural expansion of range with the aid of various ocean currents like the Gulf Stream or by hitching a ride on floating debris from the Caribbean. Ecologically speaking, Bocourt crabs and our native blue crabs have virtually the same dietary habits and both species occur together throughout some parts of their native range. Even though there is likely some competition for food and refuge habitat, it doesn’t appear at this time that one of these crabs would dominate the ecosystem over the other. It also is not evident that Bocourt crabs are reproducing and established in the Northern Gulf of Mexico to-date.

If you are a commercial crabber in the Florida Panhandle, or happen to fish a few recreational traps, we would be interested to know if you have seen this species before. Location data and any good photos of specimens would go a long way to help monitor the species occurrence in our region. You can reach out to me at Elovestrand@ufl.edu or contact your local County Extension office to pass the info my way. Happy crabbing!

by Rick O'Connor | Nov 15, 2024

Much of the phytoplankton found in the waters for the northern Gulf of Mexico are diatoms and dinoflagellates. We wrote about diatoms in our last article, here we will meet the dinoflagellates.

Like diatoms, dinoflagellates are microscopic phytoplankton drifting in the surface waters of the Gulf by the billions. We mentioned how abundant diatoms were, in the warmer seas, dinoflagellates are even more abundant. You collect them using a plankton net as you would diatoms. Observing them under the microscope they differ in a couple of ways. One, their shell is not made of clear silica but rather plates of cellulose with silica mixed in. Like diatoms, dinoflagellates possess several forms of chlorophyll but instead of fucoxanthins they possess carotenoids – giving them a brownish/red color. They also possess two hair-like tails called flagella – hence their name “dinoflagellate”. One flagella extends head to tail, the other encircles the dinoflagellate across their “girdle”. These flagella allow the cells to adjust and orient their position in the water column.

Dinoflagellates are microscopic plant-like plankton that possess two flagella.

Image: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

As with diatoms, dinoflagellates exist in the sunlit surface waters serving as “grasses of the sea”. They are an important part of the food chain and, along with their diatom cousins, produce about 50% of the world’s oxygen. But some members of this group are known for other roles they play.

Karenia brevis is the dinoflagellate primarily responsible for red tide in Florida. A plankton tow will find these organisms are always present – usually 1,000 cells/liter of water or less. Under certain conditions, these dinoflagellates begin to replicate in great numbers. Their numbers are large enough that the water will often change to a “reddish” color. In this case we are talking 1 million cells/liter or more. When disturbed, they will secrete a toxin – brevotoxin. This toxin can cause a variety of issues for marine life – and humans. Gastrointestinal, neurological, and respiratory problems in humans have all been associated with it. Red tides are famous for the large fish kills they generate and the mortality in marine mammals.

Being “plant-like” warm waters, sunlight, and nutrients will trigger a bloom. These blooms have been occurring for centuries and were logged by the Spanish explorers. Often, they generate offshore where the sunlit calm waters of the Florida shelf are bathed in nutrients from ocean currents coming from the seafloor. When wind conditions are right – these offshore blooms move inshore where they meet the nutrient rich discharge from rivers and estuaries – enhancing the blooms. Much of this discharge has higher levels of nutrients due to the actions of humans – such as fertilizers, animal and human waste.

Red tides are quite common off southwest Florida – happing frequently during the winter months. In the northern Gulf they are not as common. We do get blooms occurring here, though most are in the eastern panhandle, but sometimes the weather will drive blooms generated in southwest Florida up our way.

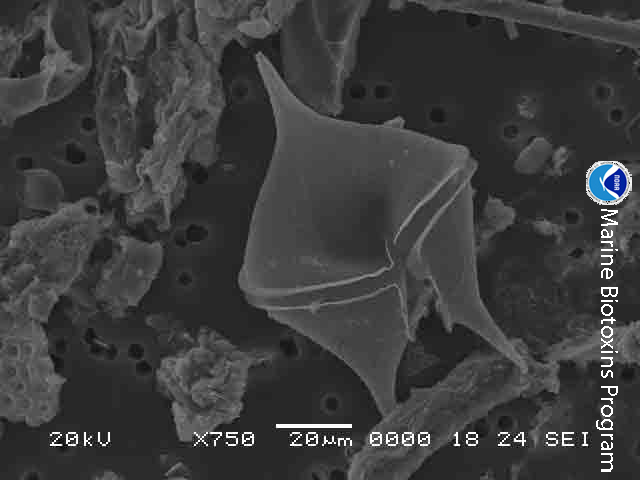

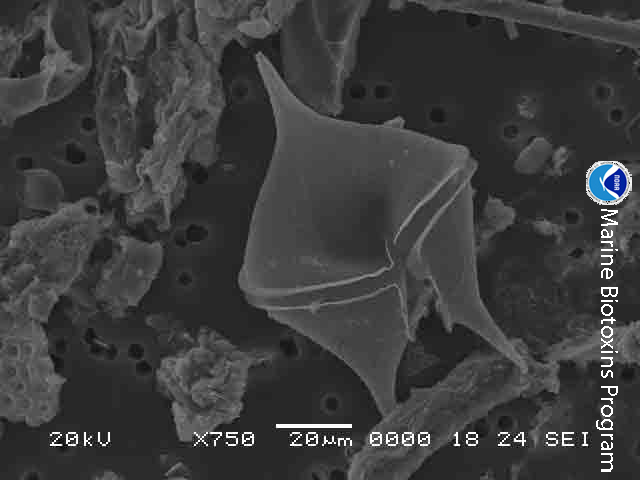

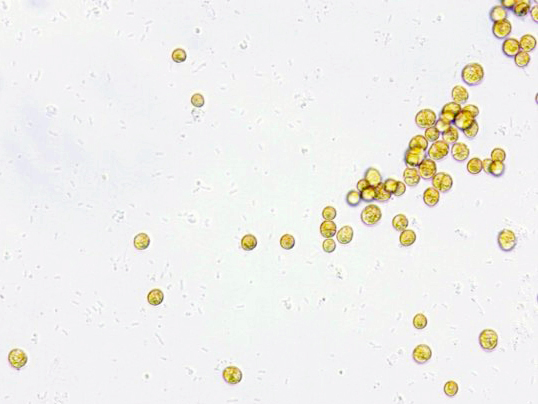

The dinoflagellate Karenia brevis.

Photo: Smithsonian Marine Station-Ft. Pierce FL

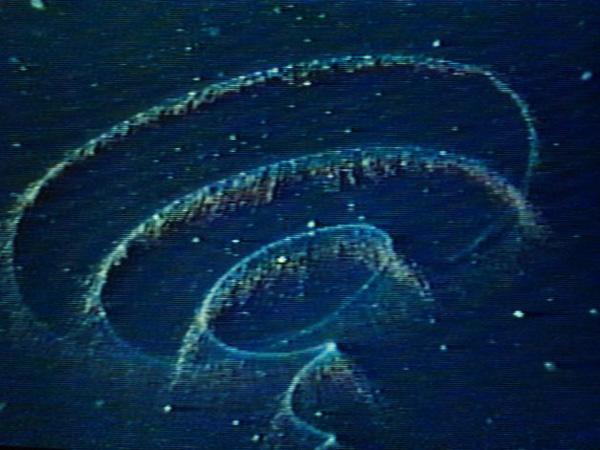

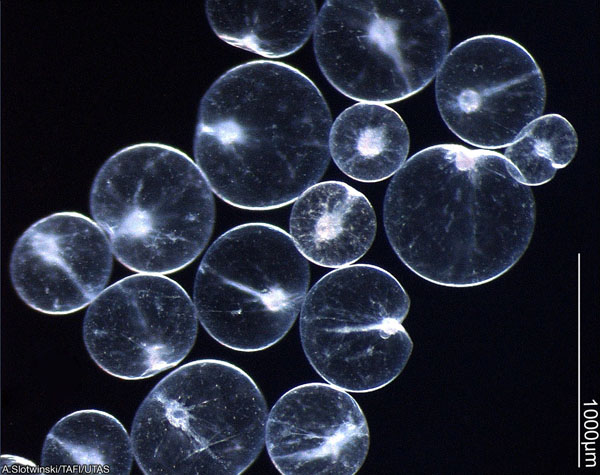

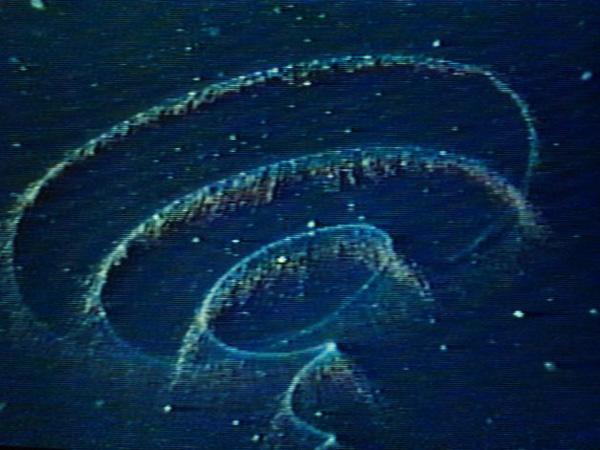

Noctiluca scitillans is another dinoflagellate that locals may know about – but did know they were dinoflagellates. What you may know it for is its ability to produce bioluminescence – “light in the sea” – what many locals called “phosphorus” when I was a kid. When disturbed a chemical reaction will create a blueish colored light. We see it during warm summer evenings when we walk through the water – or our footprints in the sand. From a boat you can see the blue light as fish swim by, or the wake from the moving boat. I remember once in high school we did a night dive near a pier where the bioluminescence from these dinoflagellates was so bright that you could see other divers, fish, and the pier without a dive light. Jim Lovell, commander of Apollo 13, tells the story of a night bombing mission he participated during the Korean War where his navigation lights went out on the return trip. The carrier was running without lights to avoid detection, but Lovell found the ship by the bioluminescent trail left by the propeller churning these dinoflagellates. This dinoflagellate is found all over the world.

Noctiluca are one of the dinoflagellates that produce bioluminescence.

Photo: University of New Hampshire.

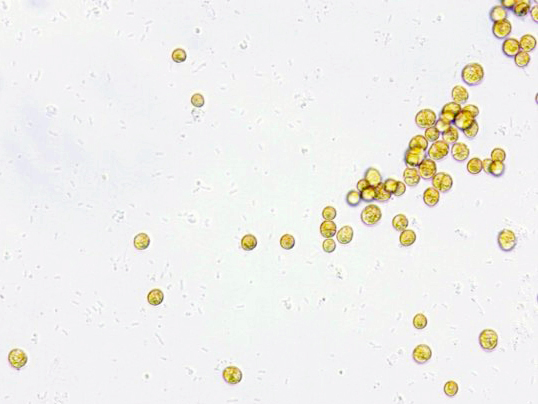

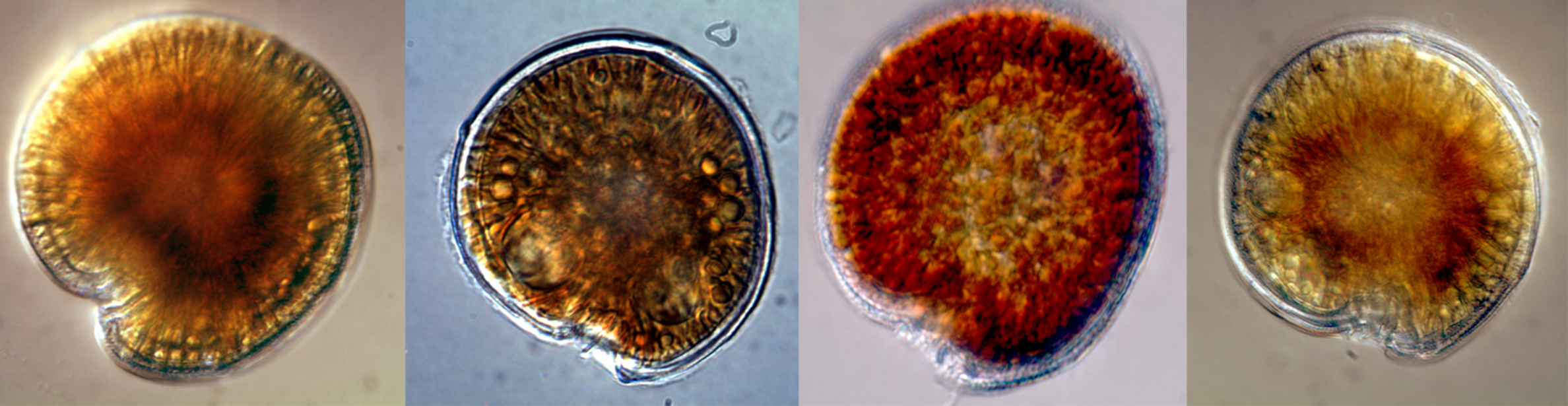

Zooxanthalle is a dinoflagellate you may not have heard of, but you may have heard of the coral bleaching that is occurring on reefs across the world. Corals are actually jellyfish and their tissue, like many jellyfish, is clear. The bright colors we are familiar with are caused by a symbiotic dinoflagellate that lives within the tissue of the corals. This symbiotic dinoflagellate is a group of several species known as zooxanthalle. In this partnership the photosynthetic zooxanthalle use waste products from the coral, and the sun, to photosynthesize. The products of photosynthesis are used to produce sugars, proteins, and other material that both the corals and the zooxanthalle need. Because of the need for sunlight, reefs usually occur in very clear – nutrient poor – waters. The bleaching we may be familiar with is caused when the reef is exposed to stress – high temperatures, pollutants, etc. and the zooxanthalle are expelled along with their photosynthetic pigments (the colors) – leaving only the clear tissue of the coral and a “white” appearance in color – bleaching.

These symbiotic zooxanthalle cells are the ones that give corals their color.

Image: NOAA

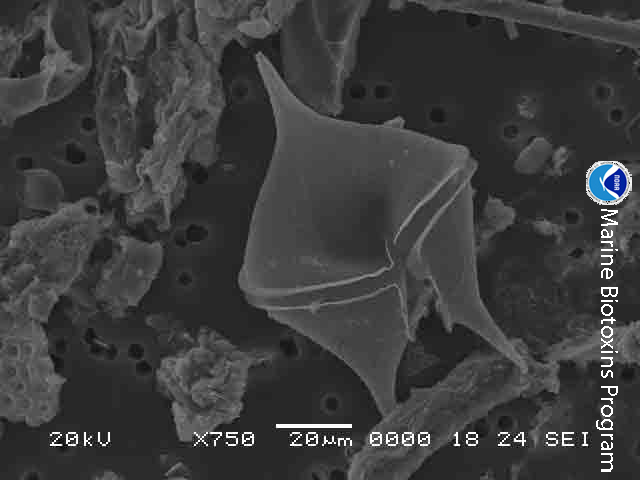

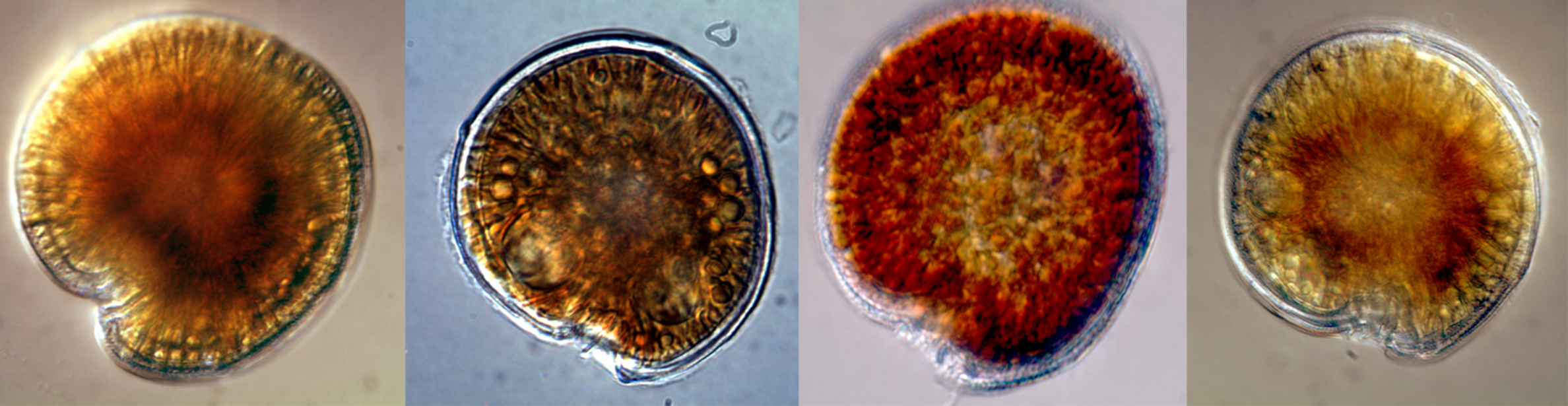

There are at least 18 species of dinoflagellates in the genus Gambierdiscus. These are not free-floating dinoflagellates, but ones they live on the bottom. You may not know them by name, but you may know them from the toxins they release when stressed – ciguatoxin. Ciguatoxins are a type of neurotoxin that can cause several illness – even death – in humans. The concentrations of ciguatoxin at the cellular level are minor and do not cause problems. However, as organisms graze on these dinoflagellates the toxins are not expelled from their bodies but are rather stored in the tissue. As you move up the food chain, no creature expels the toxins, and the concentrations increase in a process known as bioaccumulation. For humans the danger lies in eating the top predators in the food chain where the concentrations of ciguatoxin are high enough to cause problems – a condition known as ciguatera. Many who have visited the tropical parts of the world – where Gambierdiscus is most common – may have heard “you should not eat the barracuda” – or other large predators caught on a reef.

This situation has not historically been an issue for the northern Gulf of Mexico, but there are now records of this dinoflagellate north of the Florida Keys – as far north as North Carolina along the east coast. Scientists are watching the movement of this tropical group of dinoflagellates as the oceans warm.

The dinoflagellate known as Gambierdiscus. Known to cause ciguatera.

Image: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

There are thousands more species of dinoflagellates in the Gulf, and know they play many important roles in the ecology of our marine environment.

Resources

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

National Institute of Health (NIH).

by Rick O'Connor | Nov 8, 2024

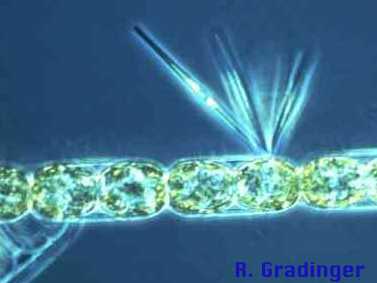

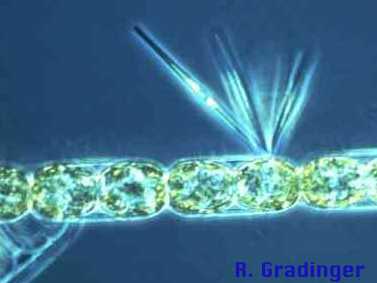

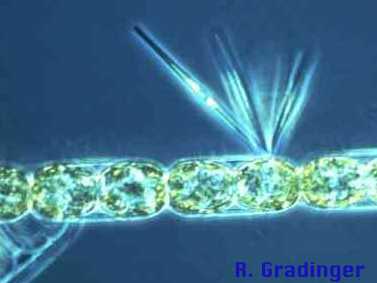

Remaining in the world of the microscopic, in this article we look at small plant-like creatures called diatoms. Diatoms are single celled algae that float in the surface waters of the Gulf of Mexico in the billions. Being plant-like, they possess chlorophyll for photosynthesis. In fact, they possess two forms of chlorophyll, and another photosynthetic pigment called fucoxanthin. Chlorophyll gives plants their characteristic green color, fucoxanthins are more yellow in color and give the diatoms the common name green-yellow algae.

Silica covered diatoms.

Photo: NOAA

To collect them scientists pull what is called a plankton net. This net is funnel shaped with the diameter of the large opening being from several inches to several feet. The mesh is of a cloth material with extremely small holes to allow water to pass but not the plankton. The plankton net is deployed off the stern of the ship/boat and towed slowly at a specific depth. Once back on board the sample can be observed in a microscope.

Plankton net.

Photo: NOAA

Diatoms are one of the more abundant microscopic plant-like algae called phytoplankton. They differ from other phytoplankters in that they do have the yellow-green color to them, but they also possess a clear glass-like shell called a frustule. This frustule is made of silica and comes in two parts. The top half is called the epitheca and the bottom half the hypotheca. The two halves fit together like the two plates of a petri dish. This frustule often has spines extending from it giving the diatom the appearance of a snowflake – and under the microscope they are beautiful. These spines actually serve a purpose. It is important they remain near the sunlit surface. To reduce sinking, these spines increase their surface area creating drag and reducing the chance they will sink. Most also produce gas pockets within the cytoplasm to make them more buoyant.

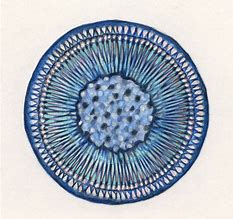

The spherical shape of the centric diatom.

Image: Florida International University

All diatoms are subdivided into two groups based on their frustule shape. Some have circular frustules and are called centric diatoms. Others are more elongated and are called pennate diatoms. Scientists currently estimate there are between 100,000 and 200,000 species of them. Though they are abundant in all the world’s oceans, they seem to be more abundant in cooler waters.

To say they play an important role in ocean ecology is an understatement. Between them and their other phytoplanktonic cousins – phytoplankton produce about 50% of the world’s oxygen. In an open ocean environment like the Gulf of Mexico where the seafloor is beyond the reach of the sun, diatoms, and other phytoplankton, are referred to as the “grasses of the sea”. They are the base of almost all marine creature’s food chain.

A phytoplankton bloom seen from space.

Photo: NOAA

When diatoms die (which is often in less than a week) their silica shells will eventually sink to the seafloor forming a layer of silica called “diatomaceous earth”. This sediment layer is commercially important as an abrasive. You will see diatomaceous earth labeled on toothpaste, household cleaners, soaps, anything with a little grit in it to help clean. It is also used in air and water filters to help purify such. You find these filters in aquariums, swimming pools, and hospitals.

If you collect a glass of water from the Gulf you are not going to see them without a microscope but know that the glass is full of these beautiful, amazing, and important marine creatures of the northern Gulf of Mexico.