by Rick O'Connor | Dec 20, 2024

In our last article we asked the question – “what are protozoans?” As we mentioned then the breakdown of the word includes “proto” which means “before”, and “zoan” which refers to animals. These are the “before animals” – meaning animal-like creatures BEFORE there were true animals.

They are single celled creatures that lack a cell wall and chlorophyll – animal-like – but they are only single celled – so, not true animals. Being animal-like means they cannot produce their own food as the diatoms, dinoflagellates, seaweeds, and true plants do. Rather, they must consume food as animals do. Some feed on diatoms and dinoflagellates. Some feed on decaying organic matter on the seafloor. Some are parasitic and feed off of a host organism. Some feed on other protozoans. And some do a combination. But they are all consumers.

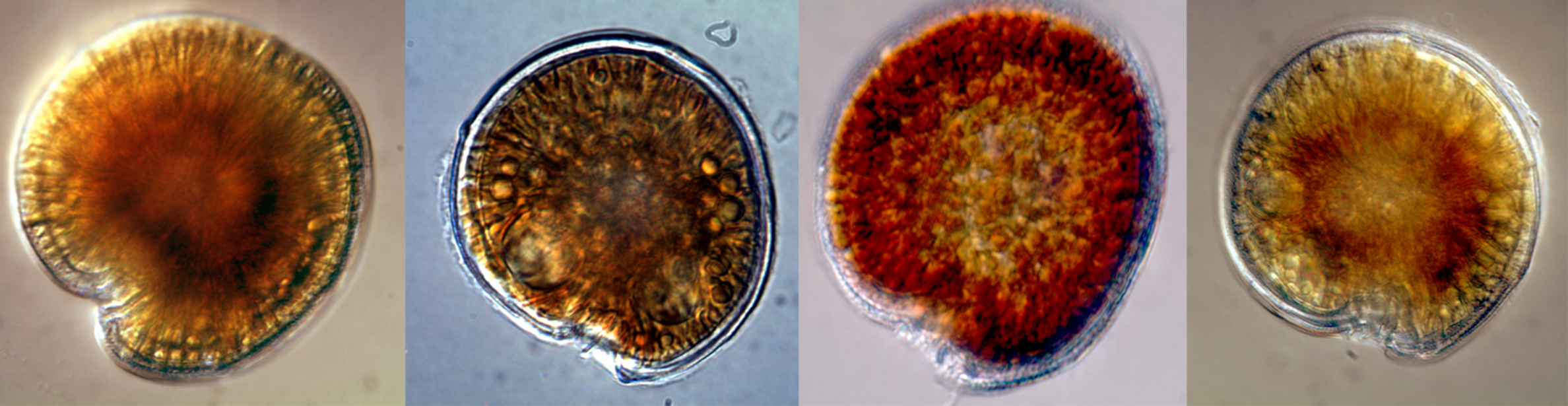

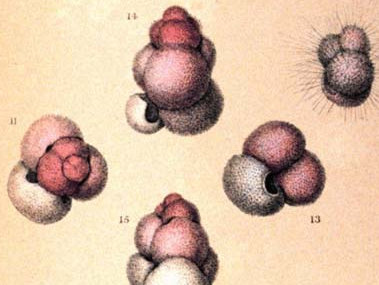

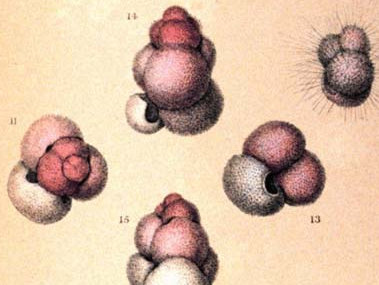

The group is classified into six phyla mostly based on how they move. One subphylum is the Sarcodinids – which move using blobby extensions of their cytoplasm called pseudopods. Under a microscope they would resemble a fried egg oozing across the slide. They are NOT fast. They can use these pseudopods not only for moving but for gathering food. I remember watching them under a scope in college. They slowly oozed across the slide engulfing most other protozoans and phytoplankton they encountered. They were like the “sharks” of the micro-world. Many live on the seafloor, or within the sediments themselves. Some are parasites. And there are a few planktonic forms. Their primary role in the marine system is moving energy through the food chain and cleaning up the environment. As with the flagellates, there two common groups in marine waters – the foraminiferans and the radiolarians.

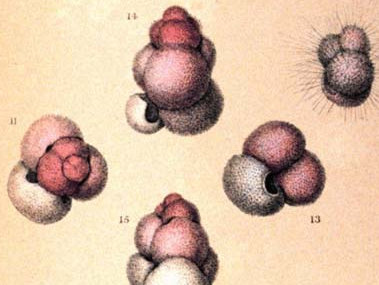

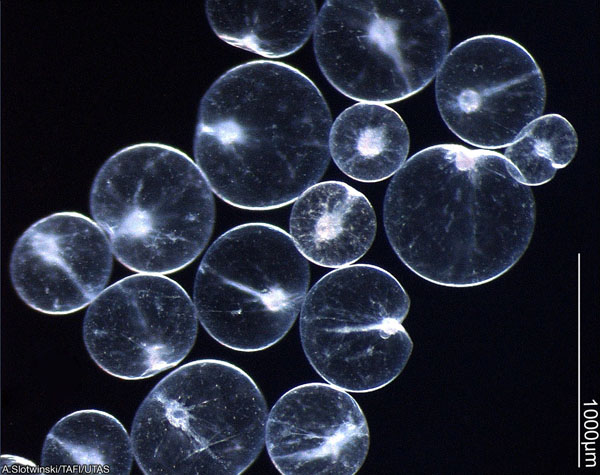

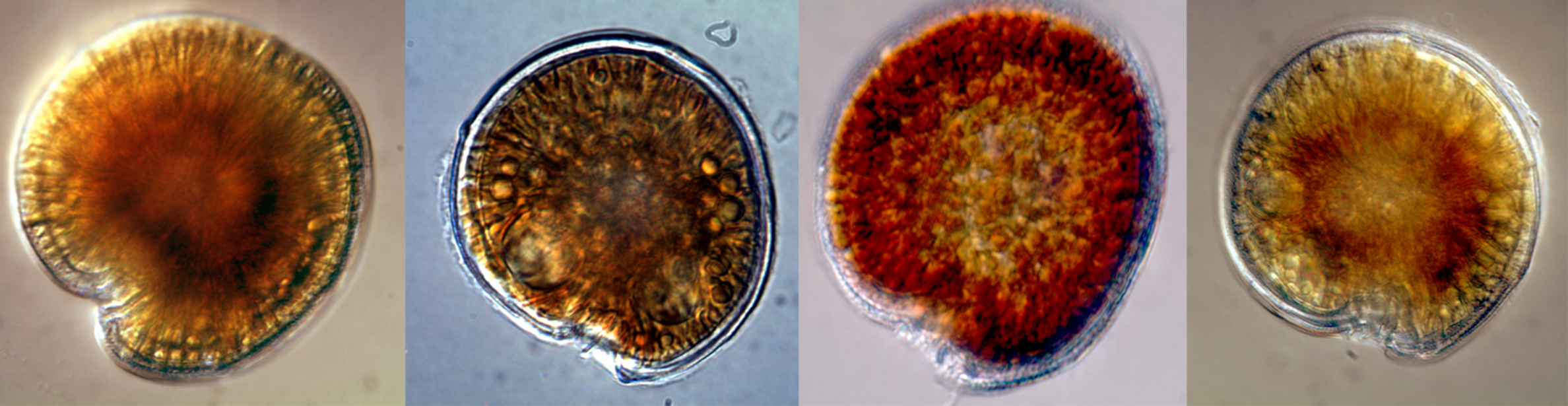

The first true oceanographic research cruise was the voyage of the HMS Challenger in 1872. The chief scientist on this first expedition was Charles Wyville Thomson, a marine geologist and one very interested in what was on the ocean floor. During the first leg of the voyage – from Europe to the America’s – they collected sediment samples several time each day. By far most of the ocean floor was made of what was called “globigerina ooze”. Globigerinids are a group of marine foraminiferans. They produce a calcium carbonate shell that is chambered. Under a microscope they look very much like seashells. They are part of the plankton layers in the ocean – what would be called “zooplankton”. Many possess spines on their shells to help reduce sinking. When they die their shells fall to the seafloor. Over time they formed the thick layers of sediment Thomson witnessed and called “ooze”. He also discovered that most of the ocean floor is covered with these microscopic shells. The Gulf of Mexico is no different. Most formaminiferans live on the seafloor and contribute to the sediment layers from there. One group forms mats on rocks that look pink in color and are responsible for the pink sands found in Bermuda.

Artist image of Globigerina.

Image: NOAA

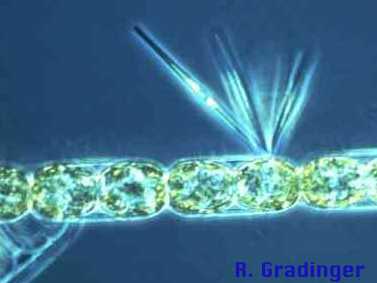

Another group of shelled amoeboid protozoans are the radiolarians. Under the microscope these are some of the most beautiful creatures you will find in the northern Gulf. Like diatoms, their shells are made of silica and look like glass. Most have spines and shapes that make them resemble snowflakes – truly beautiful. Like foraminiferans, when they die their shells settle on the seafloor and contribute to the ooze layers. Radiolarian ooze has been found as deep as 12,000 feet.

The snowflake-like shells of radiolarians.

Image: Wikipedia.

These small, microscopic amoeba like animals play an important role in moving food and energy through the Gulf. Their discovery on the seafloor helped marine geologists better understand how our oceans formed and how they have changed over time. On other beaches around the world, they have contributed to sands giving some beaches very unique colors – which are popular with tourists. They are an unknown, but important part of the marine community in the northern Gulf of Mexico.

References

Yaeger, R.G. 1996. Protozoa: Structure, Classification, Growth, and Development. Chapter 77. Medical Microbiology, 4th edition. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK8325/#A4082.

by Erik Lovestrand | Nov 22, 2024

In early November a local crabber, Kevin Martina, brought an interesting catch to the Franklin County Extension office in Apalachicola. Kevin and his brother Kenneth Martina fish for blue crabs in Apalachicola Bay and they came across what appeared at first glance to be a red-colored blue crab. In all their combined years of working crab pots, neither of them had seen a crab like this. On closer inspection at the Extension Office, there appeared to be some differences from a blue crab, other than the striking red coloration. It was the innate curiosity of our Extension Office Manager, Michelle Huber, that led us to the discovery that the crab was a species with a native range spanning Jamaica and Belize to Santa Caterina, Brazil. After Michelle showed photos of what she had found on her phone, we reached out to colleagues at the Apalachicola National Estuarine Research Reserve (ANERR) and told them we might have a Bocourt swimming crab (Callinectes bocourti). I told them that I could find no range maps indicating this species lived in our region. The nearest US Geological Survey data points for the species in the Gulf of Mexico were Alabama to the West and the Florida Everglades to the South. It was not long after the ANERR staff reached out to the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission that we received interest in confirming the identification and officially documenting the Bocourt swimming crab find.

Bocourt Swimming Crab – USGS/South Carolina DNR

The first documented occurrence of a Bocourt swimming crab in the US happened in 1950 in South Florida. Since then, there have been rare finds in AL and MS and more common occurrences from South Florida all the way up to North Carolina on the Atlantic Coast. Theories about how they arrived include possible transport of larvae in ships’ ballast water or a natural expansion of range with the aid of various ocean currents like the Gulf Stream or by hitching a ride on floating debris from the Caribbean. Ecologically speaking, Bocourt crabs and our native blue crabs have virtually the same dietary habits and both species occur together throughout some parts of their native range. Even though there is likely some competition for food and refuge habitat, it doesn’t appear at this time that one of these crabs would dominate the ecosystem over the other. It also is not evident that Bocourt crabs are reproducing and established in the Northern Gulf of Mexico to-date.

If you are a commercial crabber in the Florida Panhandle, or happen to fish a few recreational traps, we would be interested to know if you have seen this species before. Location data and any good photos of specimens would go a long way to help monitor the species occurrence in our region. You can reach out to me at Elovestrand@ufl.edu or contact your local County Extension office to pass the info my way. Happy crabbing!

by Rick O'Connor | Nov 15, 2024

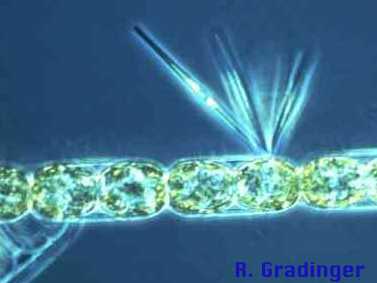

Much of the phytoplankton found in the waters for the northern Gulf of Mexico are diatoms and dinoflagellates. We wrote about diatoms in our last article, here we will meet the dinoflagellates.

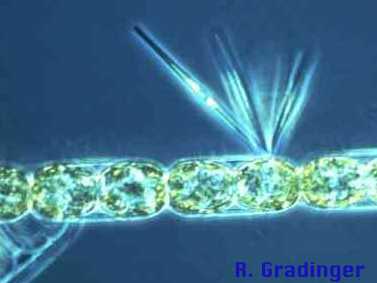

Like diatoms, dinoflagellates are microscopic phytoplankton drifting in the surface waters of the Gulf by the billions. We mentioned how abundant diatoms were, in the warmer seas, dinoflagellates are even more abundant. You collect them using a plankton net as you would diatoms. Observing them under the microscope they differ in a couple of ways. One, their shell is not made of clear silica but rather plates of cellulose with silica mixed in. Like diatoms, dinoflagellates possess several forms of chlorophyll but instead of fucoxanthins they possess carotenoids – giving them a brownish/red color. They also possess two hair-like tails called flagella – hence their name “dinoflagellate”. One flagella extends head to tail, the other encircles the dinoflagellate across their “girdle”. These flagella allow the cells to adjust and orient their position in the water column.

Dinoflagellates are microscopic plant-like plankton that possess two flagella.

Image: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

As with diatoms, dinoflagellates exist in the sunlit surface waters serving as “grasses of the sea”. They are an important part of the food chain and, along with their diatom cousins, produce about 50% of the world’s oxygen. But some members of this group are known for other roles they play.

Karenia brevis is the dinoflagellate primarily responsible for red tide in Florida. A plankton tow will find these organisms are always present – usually 1,000 cells/liter of water or less. Under certain conditions, these dinoflagellates begin to replicate in great numbers. Their numbers are large enough that the water will often change to a “reddish” color. In this case we are talking 1 million cells/liter or more. When disturbed, they will secrete a toxin – brevotoxin. This toxin can cause a variety of issues for marine life – and humans. Gastrointestinal, neurological, and respiratory problems in humans have all been associated with it. Red tides are famous for the large fish kills they generate and the mortality in marine mammals.

Being “plant-like” warm waters, sunlight, and nutrients will trigger a bloom. These blooms have been occurring for centuries and were logged by the Spanish explorers. Often, they generate offshore where the sunlit calm waters of the Florida shelf are bathed in nutrients from ocean currents coming from the seafloor. When wind conditions are right – these offshore blooms move inshore where they meet the nutrient rich discharge from rivers and estuaries – enhancing the blooms. Much of this discharge has higher levels of nutrients due to the actions of humans – such as fertilizers, animal and human waste.

Red tides are quite common off southwest Florida – happing frequently during the winter months. In the northern Gulf they are not as common. We do get blooms occurring here, though most are in the eastern panhandle, but sometimes the weather will drive blooms generated in southwest Florida up our way.

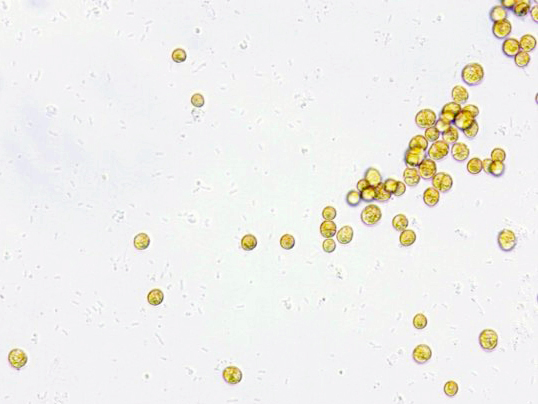

The dinoflagellate Karenia brevis.

Photo: Smithsonian Marine Station-Ft. Pierce FL

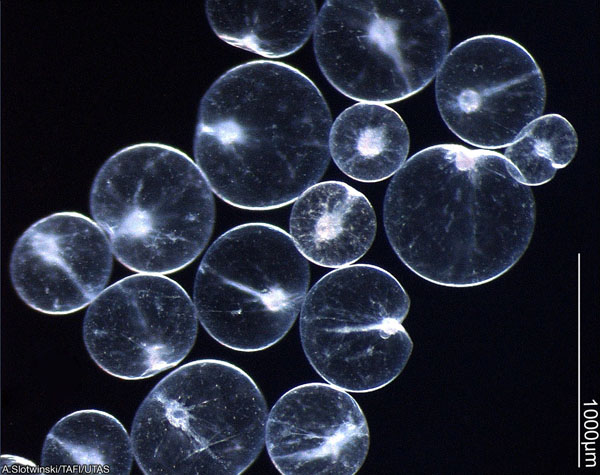

Noctiluca scitillans is another dinoflagellate that locals may know about – but did know they were dinoflagellates. What you may know it for is its ability to produce bioluminescence – “light in the sea” – what many locals called “phosphorus” when I was a kid. When disturbed a chemical reaction will create a blueish colored light. We see it during warm summer evenings when we walk through the water – or our footprints in the sand. From a boat you can see the blue light as fish swim by, or the wake from the moving boat. I remember once in high school we did a night dive near a pier where the bioluminescence from these dinoflagellates was so bright that you could see other divers, fish, and the pier without a dive light. Jim Lovell, commander of Apollo 13, tells the story of a night bombing mission he participated during the Korean War where his navigation lights went out on the return trip. The carrier was running without lights to avoid detection, but Lovell found the ship by the bioluminescent trail left by the propeller churning these dinoflagellates. This dinoflagellate is found all over the world.

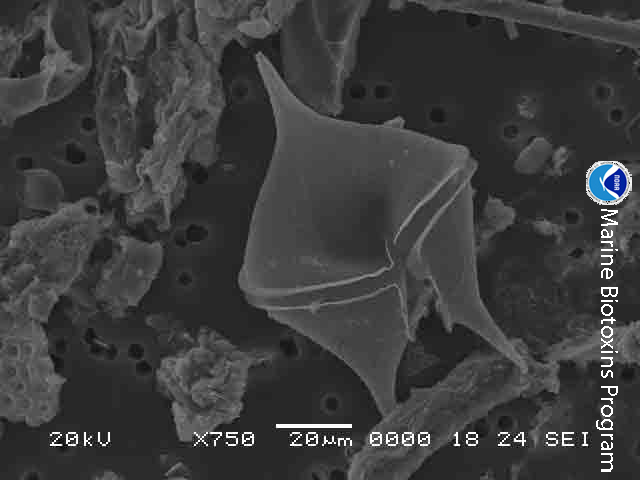

Noctiluca are one of the dinoflagellates that produce bioluminescence.

Photo: University of New Hampshire.

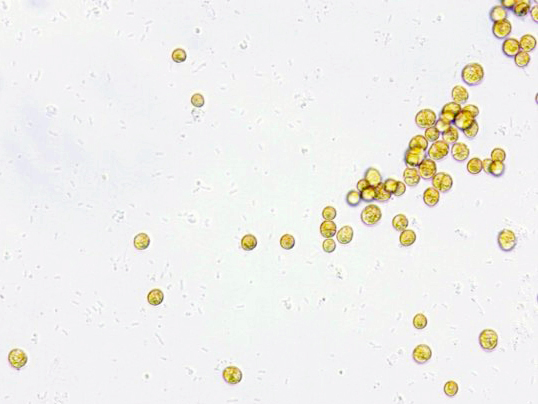

Zooxanthalle is a dinoflagellate you may not have heard of, but you may have heard of the coral bleaching that is occurring on reefs across the world. Corals are actually jellyfish and their tissue, like many jellyfish, is clear. The bright colors we are familiar with are caused by a symbiotic dinoflagellate that lives within the tissue of the corals. This symbiotic dinoflagellate is a group of several species known as zooxanthalle. In this partnership the photosynthetic zooxanthalle use waste products from the coral, and the sun, to photosynthesize. The products of photosynthesis are used to produce sugars, proteins, and other material that both the corals and the zooxanthalle need. Because of the need for sunlight, reefs usually occur in very clear – nutrient poor – waters. The bleaching we may be familiar with is caused when the reef is exposed to stress – high temperatures, pollutants, etc. and the zooxanthalle are expelled along with their photosynthetic pigments (the colors) – leaving only the clear tissue of the coral and a “white” appearance in color – bleaching.

These symbiotic zooxanthalle cells are the ones that give corals their color.

Image: NOAA

There are at least 18 species of dinoflagellates in the genus Gambierdiscus. These are not free-floating dinoflagellates, but ones they live on the bottom. You may not know them by name, but you may know them from the toxins they release when stressed – ciguatoxin. Ciguatoxins are a type of neurotoxin that can cause several illness – even death – in humans. The concentrations of ciguatoxin at the cellular level are minor and do not cause problems. However, as organisms graze on these dinoflagellates the toxins are not expelled from their bodies but are rather stored in the tissue. As you move up the food chain, no creature expels the toxins, and the concentrations increase in a process known as bioaccumulation. For humans the danger lies in eating the top predators in the food chain where the concentrations of ciguatoxin are high enough to cause problems – a condition known as ciguatera. Many who have visited the tropical parts of the world – where Gambierdiscus is most common – may have heard “you should not eat the barracuda” – or other large predators caught on a reef.

This situation has not historically been an issue for the northern Gulf of Mexico, but there are now records of this dinoflagellate north of the Florida Keys – as far north as North Carolina along the east coast. Scientists are watching the movement of this tropical group of dinoflagellates as the oceans warm.

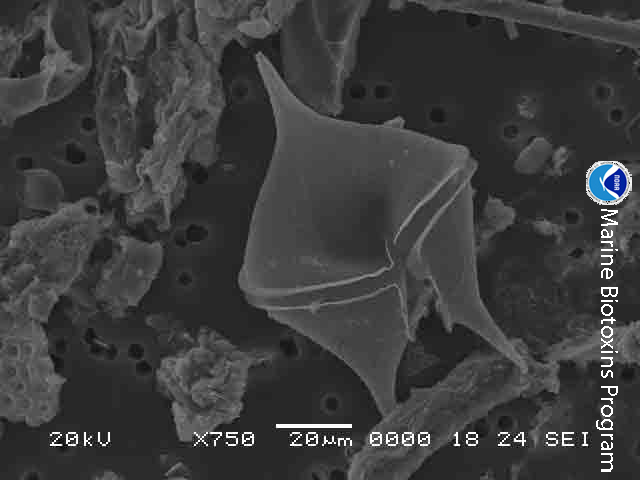

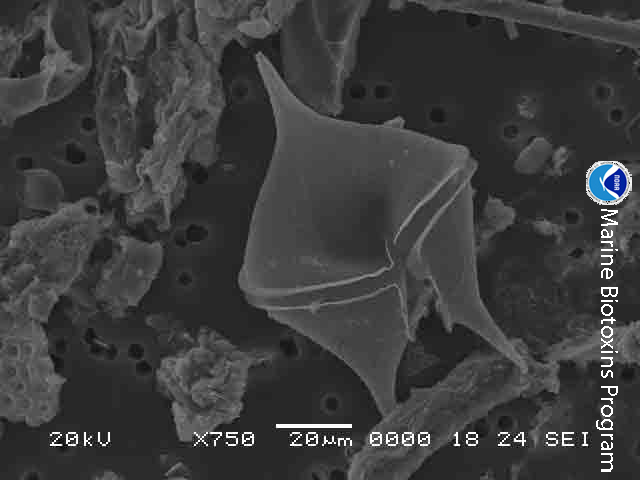

The dinoflagellate known as Gambierdiscus. Known to cause ciguatera.

Image: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

There are thousands more species of dinoflagellates in the Gulf, and know they play many important roles in the ecology of our marine environment.

Resources

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

National Institute of Health (NIH).

by Rick O'Connor | Nov 8, 2024

Remaining in the world of the microscopic, in this article we look at small plant-like creatures called diatoms. Diatoms are single celled algae that float in the surface waters of the Gulf of Mexico in the billions. Being plant-like, they possess chlorophyll for photosynthesis. In fact, they possess two forms of chlorophyll, and another photosynthetic pigment called fucoxanthin. Chlorophyll gives plants their characteristic green color, fucoxanthins are more yellow in color and give the diatoms the common name green-yellow algae.

Silica covered diatoms.

Photo: NOAA

To collect them scientists pull what is called a plankton net. This net is funnel shaped with the diameter of the large opening being from several inches to several feet. The mesh is of a cloth material with extremely small holes to allow water to pass but not the plankton. The plankton net is deployed off the stern of the ship/boat and towed slowly at a specific depth. Once back on board the sample can be observed in a microscope.

Plankton net.

Photo: NOAA

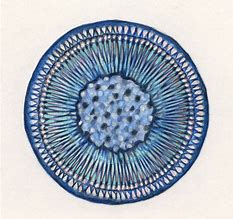

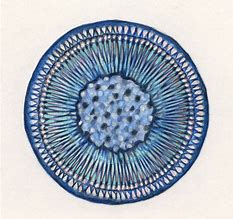

Diatoms are one of the more abundant microscopic plant-like algae called phytoplankton. They differ from other phytoplankters in that they do have the yellow-green color to them, but they also possess a clear glass-like shell called a frustule. This frustule is made of silica and comes in two parts. The top half is called the epitheca and the bottom half the hypotheca. The two halves fit together like the two plates of a petri dish. This frustule often has spines extending from it giving the diatom the appearance of a snowflake – and under the microscope they are beautiful. These spines actually serve a purpose. It is important they remain near the sunlit surface. To reduce sinking, these spines increase their surface area creating drag and reducing the chance they will sink. Most also produce gas pockets within the cytoplasm to make them more buoyant.

The spherical shape of the centric diatom.

Image: Florida International University

All diatoms are subdivided into two groups based on their frustule shape. Some have circular frustules and are called centric diatoms. Others are more elongated and are called pennate diatoms. Scientists currently estimate there are between 100,000 and 200,000 species of them. Though they are abundant in all the world’s oceans, they seem to be more abundant in cooler waters.

To say they play an important role in ocean ecology is an understatement. Between them and their other phytoplanktonic cousins – phytoplankton produce about 50% of the world’s oxygen. In an open ocean environment like the Gulf of Mexico where the seafloor is beyond the reach of the sun, diatoms, and other phytoplankton, are referred to as the “grasses of the sea”. They are the base of almost all marine creature’s food chain.

A phytoplankton bloom seen from space.

Photo: NOAA

When diatoms die (which is often in less than a week) their silica shells will eventually sink to the seafloor forming a layer of silica called “diatomaceous earth”. This sediment layer is commercially important as an abrasive. You will see diatomaceous earth labeled on toothpaste, household cleaners, soaps, anything with a little grit in it to help clean. It is also used in air and water filters to help purify such. You find these filters in aquariums, swimming pools, and hospitals.

If you collect a glass of water from the Gulf you are not going to see them without a microscope but know that the glass is full of these beautiful, amazing, and important marine creatures of the northern Gulf of Mexico.

by Thomas Derbes II | Nov 8, 2024

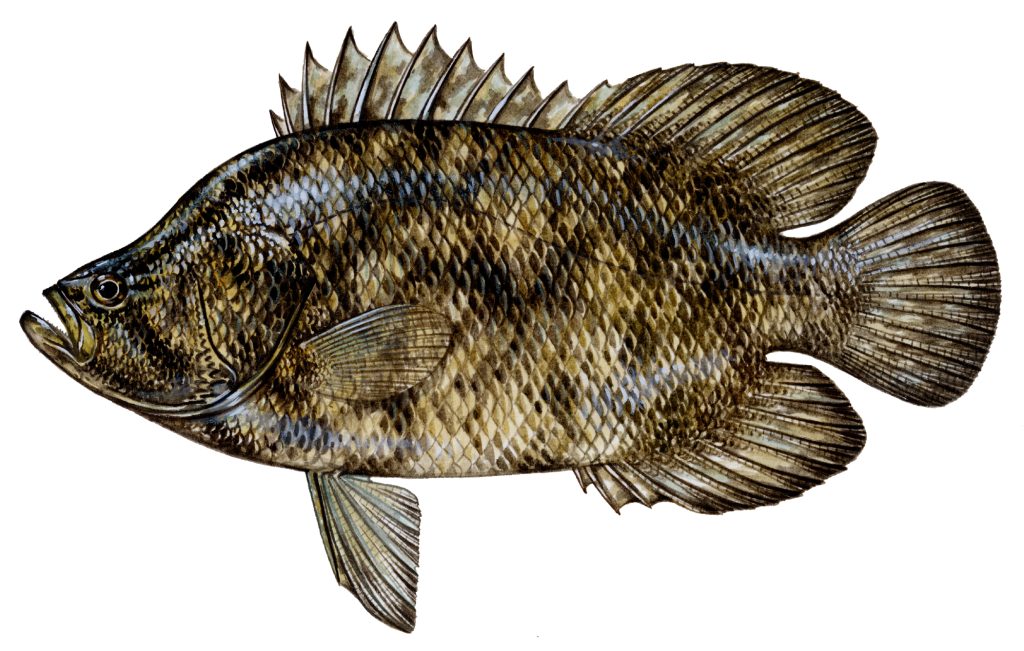

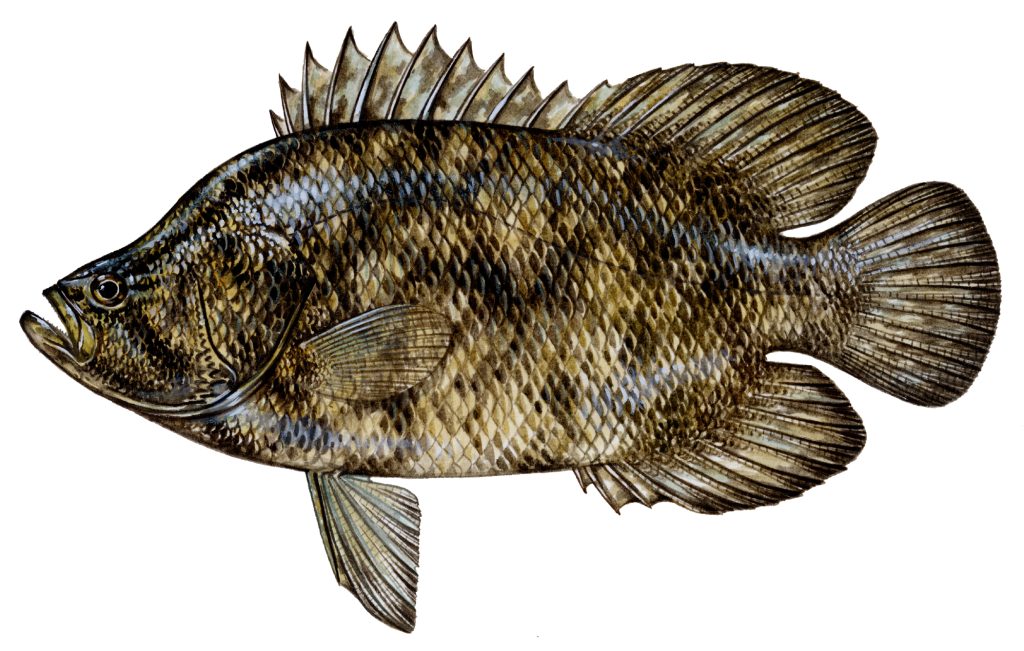

The Atlantic Tripletail (Lobotes surinamensis) is a very prized sportfish along the Florida Panhandle. Typically caught as a “bonus” fish found along floating debris, the tripletail is a hard fighting fish and excellent table fare. Just as the name implies, this fish is equipped with three “tails” that help aid it in propulsion; and also help contribute to their strong fighting spirit. In addition to the caudal fin, tripletail have very pronounced “lobed” dorsal and anal fin soft rays that sit very far back on the body, giving it the appearance of three tails (triple-tails).

Atlantic Tripletail (Lobotes surinamensis) – FWC, Diane Rome Peebles 1992

Tripletail are found in tropical and subtropical seas around the world (except the eastern Pacific Ocean) and are the only member of their family found in the Gulf of Mexico. Tripletail can be found in all saltwater environments, from the upper bays to the middle of the Gulf of Mexico. In the Florida Panhandle, tripletail begin to show up in the bays beginning in May and can be found up until October/November. They are masters of disguise, usually found floating along floating debris, crab trap buoys, navigation pilings, and floating algae like Sargassum. When tripletail are young, they are able to change their colors to match the debris, albeit it is usually a variation of yellow, brown, and black. Adult tripletail can change color as well, but the coloration is not as vibrant as the juveniles. Floating alongside debris and other floating materials protects them from predators and gives them food access. Small crustaceans, like shrimp and crabs, and small fish will gather along the floating debris, looking for protection, giving the camouflaged tripletail an easy meal.

Baby Tripletail or Leaf? – Thomas Derbes II

Tripletail are opportunistic feeders that are what I classify as “lazy hunters.” Tripletail will hang out along any floating debris and wait for the food to come to them. They typically will not chase their prey items too far and will abandon the hunt if they expend too much energy. Since they are opportunistic feeders, their diet varies widely, but they cannot resist a baby blue crab, shrimp, or small baitfish like menhaden (Brevoortia patronus) that might visit their floating oasis. When further offshore, it is not uncommon to find many tripletail “laying out” on sargassum or floating debris. I personally have seen a dozen full-sized tripletail inside of a large traffic barrel 25 miles offshore that saved a skunk of a deep-dropping fishing trip.

Tripletail Caught Off An Oyster Farm – Brandon Smith

When targeting tripletail, anglers will typically sit at the highest point of the boat (some anglers have towers for spotting tripletail) and cruise along floating crab trap buoys, pilings, and sometimes oyster farms looking for Tripletail. These fish are very easily spooked, and a slow, quiet approach is best. Once in casting distance, toss your preferred bait (I typically want to have baby crabs or live shrimp when targeting tripletail) close to the floating structure, but not too close to spook the fish. You can usually watch the fish eat your bait (another added bonus) and once you set the hook, the fight is on! In the state of Florida, tripletail must be a minimum of 18 inches and there is a daily bag limit of 2 fish per person. Be very careful handling tripletail as they have very sharp dorsal and anal fins and their operculum (gill cover) is also very sharp with hidden spines.

So next time you’re out fishing and see something floating, make sure you give it a good look over. There might be a camouflaged tripletail that you can add to your fish box!

Tripletail Caught While Working Oyster Gear – Thomas Derbes

by Rick O'Connor | Aug 30, 2024

Introduction

The bay scallop (Argopecten irradians) was once common in the lower portions of the Pensacola Bay system. However, by 1970 they were all but gone. Closely associated with seagrass, especially turtle grass (Thalassia testudinum), some suggested the decline was connected to the decline of seagrass beds in this part of the bay. Decline in water quality and overharvesting by humans may have also been a contributor. It was most likely a combination of these factors.

Scalloping is a popular activity in our state. It can be done with a simple mask and snorkel, in relatively shallow water, and is very family friendly. The decline witnessed in the lower Pensacola Bay system was witnessed in other estuaries along Florida’s Gulf coast as well. Today commercial harvest is banned, and recreational harvest is restricted to specific months and to the Big Bend region of the state. With the improvements in water quality and natural seagrass restoration, it is hoped that the bay scallop may return to lower Pensacola Bay.

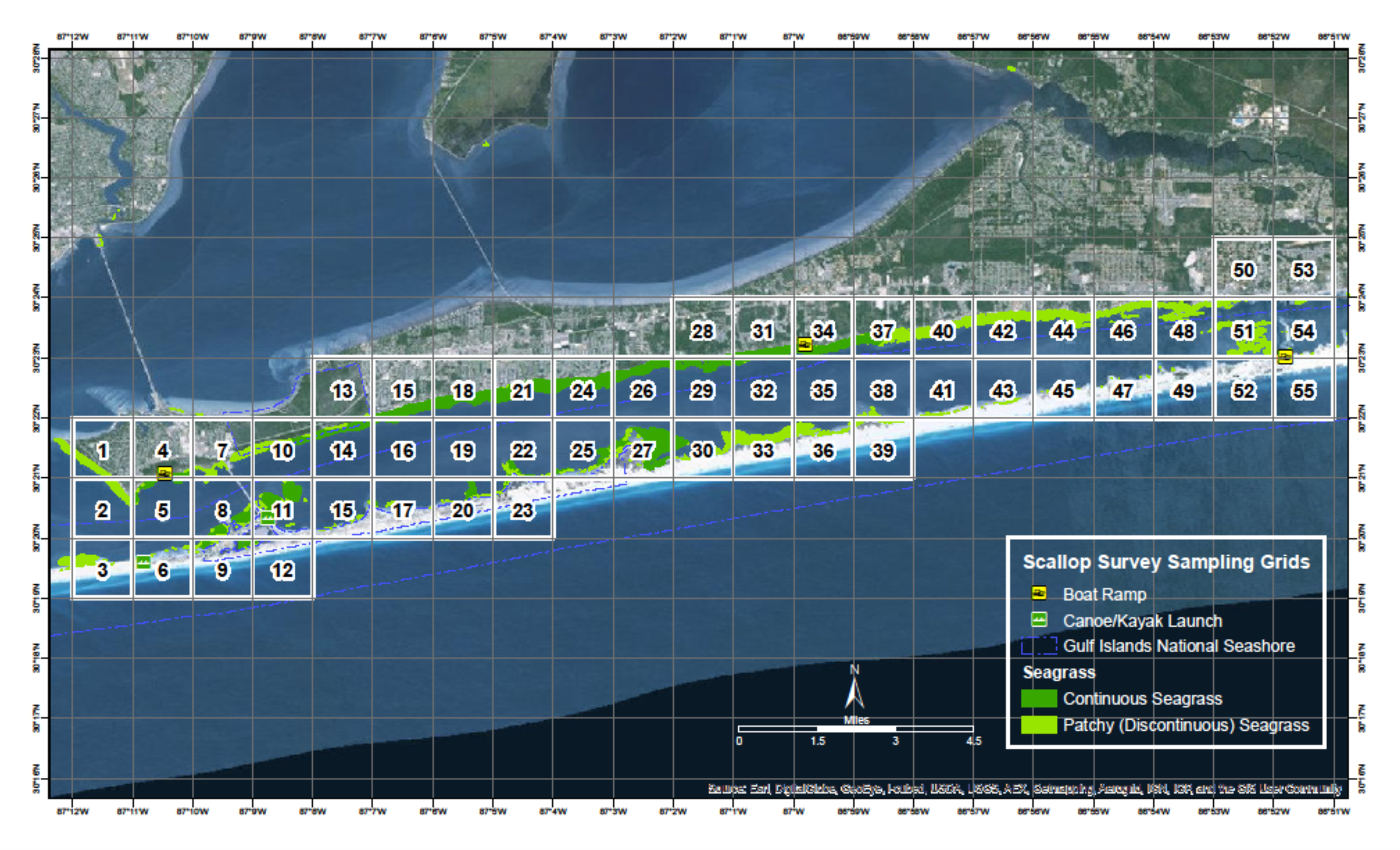

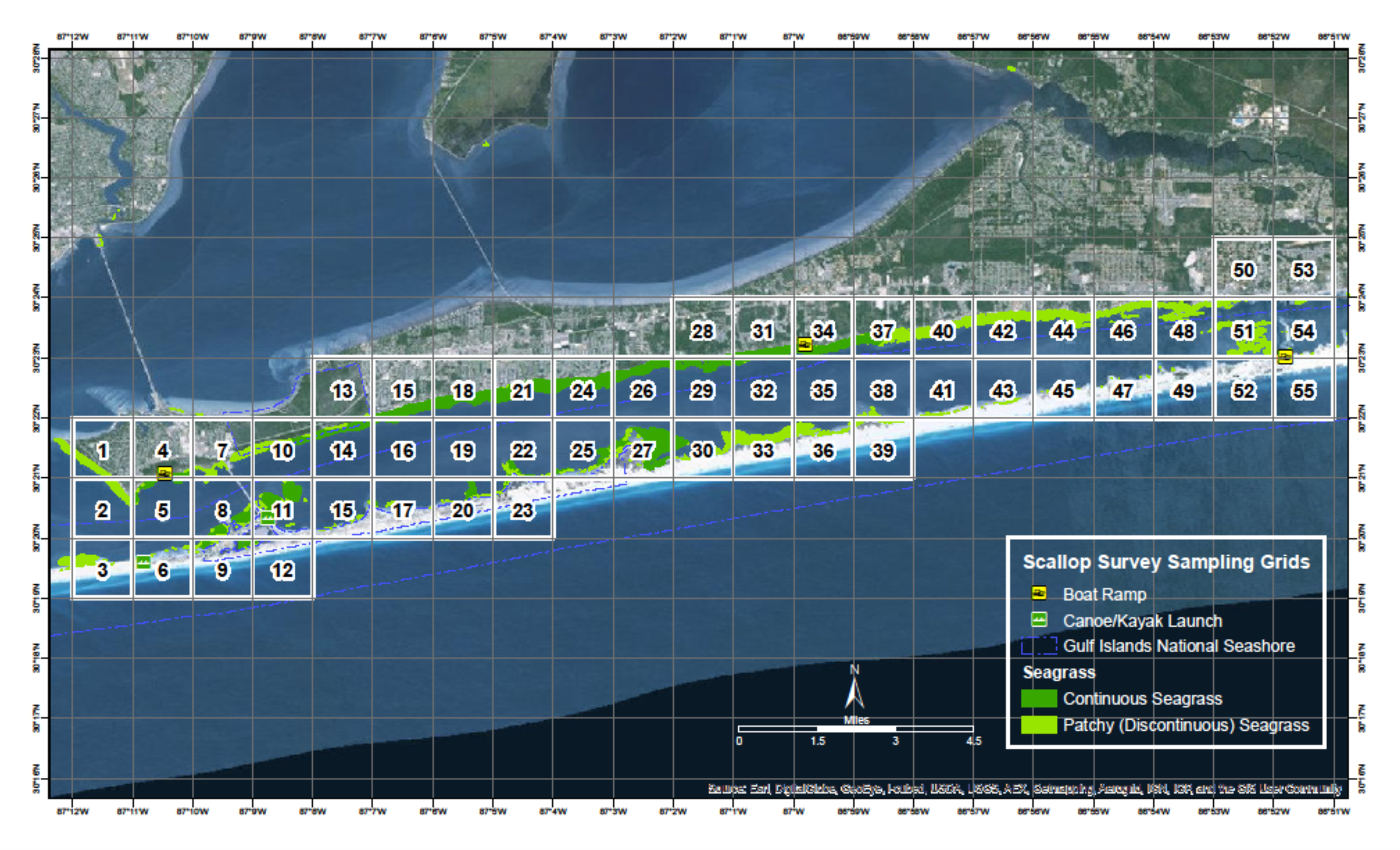

Since 2015 Florida Sea Grant has held the annual Pensacola Bay Scallop Search. Trained volunteers survey pre-determined grids within Big Lagoon and Santa Rosa Sound. Below is the report for both the 2024 survey and the overall results since 2015.

Methods

Scallop searchers are volunteers trained by Florida Sea Grant. Teams are made up of at least three members. Two snorkel while one is the data recorder. More than three can be on a team. Some pre-determined grids require a boat to access, others can be reached by paddle craft or on foot.

Once on site the volunteers extend a 50-meter transect line that is weighted on each end. Also attached is a white buoy to mark the end of the line. The two snorkelers survey the length of the transect, one on each side, using a 1-meter PVC pipe to determine where the area of the transect ends. This transect thus covers 100m2. The surveyors record the number of live scallops they find within this area, measure the height of the first five found in millimeters using a small caliper, which species of seagrass are within the transect, the percent coverage of the seagrass, whether macroalgae are present or not, and any other notes of interest – such as the presence of scallop shells or scallop predators (such as conchs and blue crabs). Three more transects are conducted within the grid before returning.

The Pensacola Scallop Search occurs during the month of July.

2024 Results

A record 168 volunteers surveyed 15 of the 66 1-nautical mile grids (23%) between Big Lagoon State Park and Navarre Beach. 152 transects (15,200m2) were surveyed logging 133 scallops. An additional 50 scallops were found outside the official transect for a total of 183 scallops for 2024.

2024 Big Lagoon Results

75 volunteers surveyed 7 of the 11 grids (64%) within the Big Lagoon. 67 transects were conducted covering 6,700m2.

101 scallops were logged with an additional 42 found outside the official transects. This equates to 3.02 scallops/200m2. Scallop searchers reported blue crabs and conchs, both scallop predators, as well as some sea urchins. All three species of seagrass were found (Thalassia, Halodule, and Syringodium). Seagrass densities ranged from 5-100%. Macroalgae was present in six of the seven grids (86%) but was never abundant.

2024 Santa Rosa Sound Results

93 volunteers surveyed 8 of the 55 grids (14%) in Santa Rosa Sound. 85 transects were conducted covering 8,500m2.

32 scallops were logged with an additional 8 found outside the official transects. This equates to 0.76 scallops/200m2. Scallop searchers reported blue crabs, conchs, and sand dollars. All three species of seagrass were found. Seagrass densities ranged from 50-100%. Macroalgae was present in five of the eight grids (62%) and was abundant in grids surveyed on the eastern end of the survey area.

2015 – 2024 Big Lagoon Results

| Year |

No. of Transects |

No. of Scallops |

Scallops/200m2 |

| 2015 |

33 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2016 |

47 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2017 |

16 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2018 |

28 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2019 |

17 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2020 |

16 |

1 |

0.12 |

| 2021 |

18 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2022 |

38 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2023 |

43 |

2 |

0.09 |

| 2024 |

67 |

101 |

3.02 |

| Big Lagoon Overall |

323 |

104 |

0.64 |

2015 – 2024 Santa Rosa Sound Results

| Year |

No. of Transects |

No. of Scallops |

Scallops/200m2 |

| 2015 |

01 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2016 |

01 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2017 |

01 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2018 |

01 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2019 |

01 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2020 |

01 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2021 |

20 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2022 |

40 |

2 |

0.11 |

| 2023 |

28 |

2 |

0.14 |

| 2024 |

85 |

32 |

0.76 |

| Santa Rosa Sound Overall |

1731 |

36 |

0.42 |

1 Transects were conducted during these years but data for Santa Rosa Sound was logged by an intern with the Santa Rosa County Extension Office and is currently unavailable.

Discussion

Based on a Florida Fish and Wildlife Research Institute publication in 2018, the final criteria are used to classify scallop populations in Florida.

| Scallop Population / 200m2 |

Classification |

| 0-2 |

Collapsed |

| 2-20 |

Vulnerable |

| 20-200 |

Stable |

Based on this, over the last nine years we have surveyed, the populations in lower Pensacola Bay are still collapsed. However, you will notice that in 2024 the population in Big Lagoon moved from collapsed to vulnerable for this year alone.

There are some possible explanations for this.

- The survey effort in Big Lagoon was stronger than Santa Rosa Sound. 75 volunteers surveyed 7 of the 11 grids. This equates to 11 volunteers / grid surveyed and 64% of the survey area was covered. With Santa Rosa Sound there were 93 volunteers who surveyed 8 of the 55 grids. This equates to 12 volunteers / grid surveyed but only 14% of the survey area was covered. Most of the SRS grids surveyed were in the Gulf Breeze/Pensacola Beach area. More effort east of Big Sabine may yield more scallops found.

- There is the possibility of different teams counting the same scallops. Each grid is 1-nautical mile, so the probability of one team laying their transect over an area another team did is low, but not zero.

- It is known that scallops have periodic population booms. Our search this year may have witnessed this. We will know if encounters significantly decrease in 2025.

Whether there was double counting this year or not, the frequency of encounter was much higher than in previous years. There were multiple reports from the public on social media about scallop encounters as well, and in some places we did not survey. It is also understood that scallops mass spawn. So, high density populations are required for reproductive success. The “boom” we witnessed this year suggests that there is a population of scallops – albeit a collapsed one – in our bay. It is important for locals NOT to harvest scallops from either body of water. First, it is illegal. Second, any chance of recovering this lost population will be lost if the adult population densities are not high enough for reproductive success.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank ALL 168 volunteers who surveyed this year. We obviously could not have done this without you.

Below are the “team captains”.

Harbor Amiss Glen Grant Eric Stone

David Anderson Phil Harter Neil Tucker

Laura Baker Gina Hertz Christian Wagley

Melinda Bennett Sean Hickey Jaden Wielhouwer

Samantha Bergeron (USM class) John Imhof Keith Wilkins

Cheri Bone Jason Mellos Christy Woodring

Cindi Cagle Greg Patterson

Cher Clary Kelly Rysula

A team of scallop searchers celebrates after finding a few scallops in Pensacola Bay.

Volunteer measures a scallop he found. Photo: Abby Nonnenmacher

Rick O’Connor Florida Sea Grant; Escambia County

Thomas Derbes II Florida Sea Grant; Santa Rosa County