by Daniel J. Leonard | Sep 3, 2020

Overcup on the edge of a wet weather pond in Calhoun County. Photo courtesy of Daniel Leonard.

Haunting alluvial river bottoms and creek beds across the Deep South, is a highly unusual oak species, Overcup Oak (Quercus lyrata). Unlike nearly any other oak, and most sane people, Overcups occur deep in alluvial swamps and spend most of their lives with their feet wet. Though the species hides out along water’s edge in secluded swamps, it has nevertheless been discovered by the horticultural industry and is becoming one of the favorite species of landscape designers and nurserymen around the South. The reasons for Overcup’s rise are numerous, let’s dive into them.

The same Overcup Oak thriving under inundation conditions 2 weeks after a heavy rain. Photo courtesy Daniel Leonard.

First, much of the deep South, especially in the Coastal Plain, is dominated by poorly drained flatwoods soils cut through by river systems and dotted with cypress and blackgum ponds. These conditions call for landscape plants that can handle hot, humid air, excess rainfall, and even periodic inundation (standing water). It stands to reason our best tree options for these areas, Sycamore, Bald Cypress, Red Maple, and others, occur naturally in swamps that mimic these conditions. Overcup Oak is one of these hardy species. It goes above and beyond being able to handle a squishy lawn, and is often found inundated for weeks at a time by more than 20’ of water during the spring floods our river systems experience. The species has even developed an interested adaptation to allow populations to thrive in flooded seasons. Their acorns, preferred food of many waterfowl, are almost totally covered by a buoyant acorn cap, allowing seeds to float downstream until they hit dry land, thus ensuring the species survives and spreads. While it will not survive perpetual inundation like Cypress and Blackgum, if you have a periodically damp area in your lawn where other species struggle, Overcup will shine.

Overcup Oak leaves in August. Note the characteristic “lyre” shape. Photo courtesy Daniel Leonard.

Overcup Oak is also an exceedingly attractive tree. In youth, the species is extremely uniform, with a straight, stout trunk and rounded “lollipop” canopy. This regular habit is maintained into adulthood, where it becomes a stately tree with a distinctly upturned branching habit, lending itself well to mowers and other traffic underneath without having to worry about hitting low-hanging branches. The large, lustrous green leaves are lyre-shaped if you use your imagination (hence the name, Quercus lyrata) and turn a not-unattractive yellowish brown in fall. Overcups especially shine in the winter when the whitish gray shaggy bark takes center stage. The bark is very reminiscent of White Oak or Shagbark Hickory and is exceedingly pretty relative to other landscape trees that can be successfully grown here.

Finally, Overcup Oak is among the easiest to grow landscape trees. We have already discussed its ability to tolerate wet soils and our blazing heat and humidity, but Overcups can also tolerate periodic drought, partial shade, and nearly any soil pH. They are long-lived trees and have no known serious pest or disease problems. They transplant easily from standard nursery containers or dug from a field (if it’s a larger specimen), making establishment in the landscape an easy task. In the establishment phase, defined as the first year or two after transplanting, young transplanted Overcups require only a weekly rain or irrigation event of around 1” (wetter areas may not require any supplemental irrigation) and bi-annual applications of a general purpose fertilizer, 10-10-10 or similar. After that, they are generally on their own without any help!

Typical shaggy bark on 7 year old Overcup Oak. Photo courtesy Daniel Leonard.

If you’ve been looking for an attractive, low-maintenance tree for a pond bank or just generally wet area in your lawn or property, Overcup Oak might be your answer. For more information on Overcup Oak, other landscape trees and native plants, give your local UF/IFAS County Extension office a call!

by Rick O'Connor | Jun 26, 2020

This is a good name for this group. They are mollusk that have two shells. They tried “univalve” with the snails and slugs, but that never caught on – gastropods it is for them. The bivalves are an interesting, and successful, group. They have taken the shell for protection idea to the limit – they are COMPLETELY covered with shell. No predators… no way. But they do have predators – we will talk more on that.

An assortment of bivalves, mostly bay scallop.

Photo: Florida Department of Environmental Protection.

As you might expect, with the increase in shell there is a decrease in locomotion – as a matter of fact, many species do not move at all (they are sessile). But in a sense, they do not care. They are completely covered and protected. Again, we will talk more about how well that works.

The two shells (valves) are connected on the dorsal side of the animal and hinged together by a ligament. Their bodies are laterally compressed to fit into a shell that is aerodynamic for burrowing through soft muds and sands. Their “heads” are greatly reduced (even missing in some) but they do have a sensory system. Along the edge of the mantle chemoreceptive cells (smell and taste) can be found and many have small ocelli, which can detect light. The scallops take it a step further by having actually eyes – but they do live on the surface and they do move around – so they are needed.

The shells are hinged together at the umbo with “teeth like structures and the shells open and close using a pair of adductor muscles. Many shells found on the beach will have “scars” which are the point of contact for these muscles. They range is size from the small seed clams (2mm – 0.08”) to the giant clam of the Indo-Pacific (1m – 3.4 ft) and 2500 lbs.! Most Gulf bivalves are more modest in size.

Being slow burrowing benthic animals, sand and mud can become a problem when feeding and breathing. In response, many bivalves have developed modified gills to help remove this debris, and many actually remove organic particles using it as a source of food. Many others will fuse their mantle to the shell not allowing sediment to enter. But some still does and, if not removed, will be covered by a layer of nacreous material forming pearls. All bivalves can produce pearls. Only those with large amounts of nacreous material produce commercially valuable ones.

Coquina are a common burrowing clam found along our beaches.

Photo: Flickr

Another feature is the large foot, used for digging a burrowing in the more primitive forms. It is the foot we eat when we eat clams. They can turn their bodies towards the substrate, begin digging with their foot but also using their excurrent from breathing to form a sort of jet to help move and loosen the sand as they go – very similar to the way we set pilings for piers and bridges today.

These are the earliest forms of bivalves – the burrowers. Most are known as clams and most live where the sediment is soft. Located near their foot is a sense organ called a statocyst that lets them know their orientation in the environment. Most have their mantles fused to their shells so sand cannot enter the empty spaces in the body. To channel water to the gills, they have developed tubes called siphons which act as snorkels. Most burrow only a few inches, some burrow very deep and they are even more streamlined and elongated.

Some have evolved to burrow into harder material such as coral or wood. One of the more common ones is an animal called a shipworm. Called this by mariners because of the tunnels they dig throughout the hulls of wooden ships, they are not worms but a type of clam that have learned to burrow through the wood consuming the sawdust of their actions. They have very reduced shells and a very long foot.

This cluster of green mussels occupies space that could be occupied by bivavles like osyters.

Other bivalves secrete a fibrous thread from their foot that is used to grab, hold, and sometimes pull the animal along. These are called byssal threads. Many will secrete hundreds of these, allow them to “tan” or dry, reduce their foot, and now are attached by these threads. The most famous of this group are the mussels. Mussels are a popular seafood product and are grown commercial having them attach to ropes hanging in the water.

Another method of attachment is to literally cement your self to the bottom. Those bivalves who do this will usually lay on their side when they first settle out from their larval stage and attach using a fluid produced by the animal. This fluid eventually cements them to the bottom and the shell attached is usually longer than the other side, which is facing the environment. The most famous of these are the oysters. Oysters basically have lost both their “head” and the foot found in other bivalves. These sessile bivalves are very dependent on tides and currents to help clear waste and mud from their bodies.

Oysters are a VERY popular seafood product along the Gulf coast.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Then there are the bivalves who actually live on the bottom – not attached – and are able to move, or even swim. Most of these have well developed tentacles and ocelli to detect danger in the environment and some, like the scallops, can actually “clap their shells together” to create a jet current and swim. This is usually done when they detect danger, such as a starfish, and they have been known to swim up to three feet. Some will use this jet as a means of digging a depression in the sand they can settle in. In this group, the adductor has been reduced from two (the number usually found in bivalves) to one, and the foot is completely gone.

As you might guess, reproduction is external in this group. Most have male and female members but some species (such as scallops and shipworms) are hermaphroditic. The gametes are released externally at the same time in an event called a mass spawning. To trigger when this should happen, the bivalves pay attention to water temperature, tides, and pheromones released by the opposite sex or by the release of the gametes themselves.

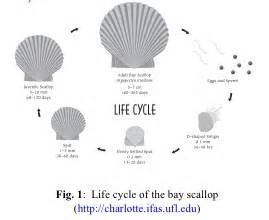

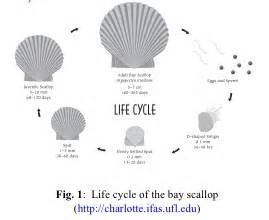

Scallop life cycle.

Image: University of Florida IFAS

The fertilized eggs quickly develop into a planktonic larva known as a veliger. This veliger is ciliated and can swim with the current to find a suitable settling spot. Some species have long lived veliger stages. Oysters are such and the dispersal of their veliger can travel as far as 800 miles! Once the larval stage ends, they settle as “spat” (baby shelled bivalves) on the substrate and begin their lives. Some species (such as scallop) only live for a year or two. Others can live up to 10 years.

As a group, bivalves are filter feeders, filtering organic particles and phytoplankton as small as 1 micron (1/1,000,000-m… VERY small). In doing this they do an excellent job of increasing water clarity which benefits many other creatures in the community. As a matter of fact, many could not survive without this “eco-service” and the loss of bivalves has triggered the loss of both habitat and species in the Gulf region. Restoration efforts (particularly with oysters) is as much for the enhancement of the environment and diversity as it is for the commercial value of the oyster.

Now… predators… yes, they have many. Though they have completely covered their bodies with shell, there are many animals that have learned to “get in there”. Starfish and octopus are famous for their abilities to open tightly closed shells. Rays, some fish, and some turtles and birds have modified teeth (or bills) to crush the shell or cut the adductor muscle. Sea otters have learned the trick to crush them with rocks and some local shorebirds will drop them on roads and cars trying to access them. And then there are humans. We steam them to open the shell and cut their adductor muscle to reach the sweet meat inside.

It is a fascinating group – and a commercial valuable one as well. Lots of bivalves are consumed in some form or fashion worldwide. Take some time at the beach to collect their shells as enjoy the great diversity and design within this group. EMBRACE THE GULF!

by Andrea Albertin | Apr 9, 2020

Pitt Spring in the Florida Panhandle is one of more than 1,000 freshwater springs in the state. Springs serve as ‘windows’ to groundwater quality, since the water that flows from them comes largely from the Upper Floridan Aquifer. Photo: A. Albertin

As Florida residents, we are so fortunate to have the Floridan Aquifer lying below us, one of the most productive aquifer systems in the world. The aquifer underlies an area of about 100,000 square miles that includes all of Florida and extends into parts of Alabama, Georgia and South Carolina, as well as parts of the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico (Figure 1). The Floridan Aquifer consists of the Upper and Lower Floridan Aquifer.

Figure 1. Map of the extent of the Floridan Aquifer. Areas in gray show where the aquifer is buried deep below the land surface, while areas in light brown indicate where the aquifer is at land surface. Many springs in Florida are found in these light brown areas. Source: USGS Publication HA 730-G.

Aquifers are immense underground zones of permeable rocks, rock fractures and unconsolidated (or loose) material, like sand, silt and clay that hold water and allow water to move through them. Both fresh and saltwater fill the pores, fissures and conduits of the Floridan Aquifer. Saltwater, which is more dense than freshwater, is found in all areas of the deeper aquifer below the freshwater.

The thickness of the Floridan Aquifer varies widely. It ranges from 250 ft. thick in parts of Georgia, to about 3,000 ft. thick in South Florida. Water from the Upper Floridan Aquifer is potable in most parts of the state and is a major source of groundwater for more than 11 million residents. However, in areas such as the far western panhandle and South Florida, where the Floridan Aquifer is very deep, the water is too salty to be potable. Instead, water from aquifers that lie above the Floridan is used for water supply.

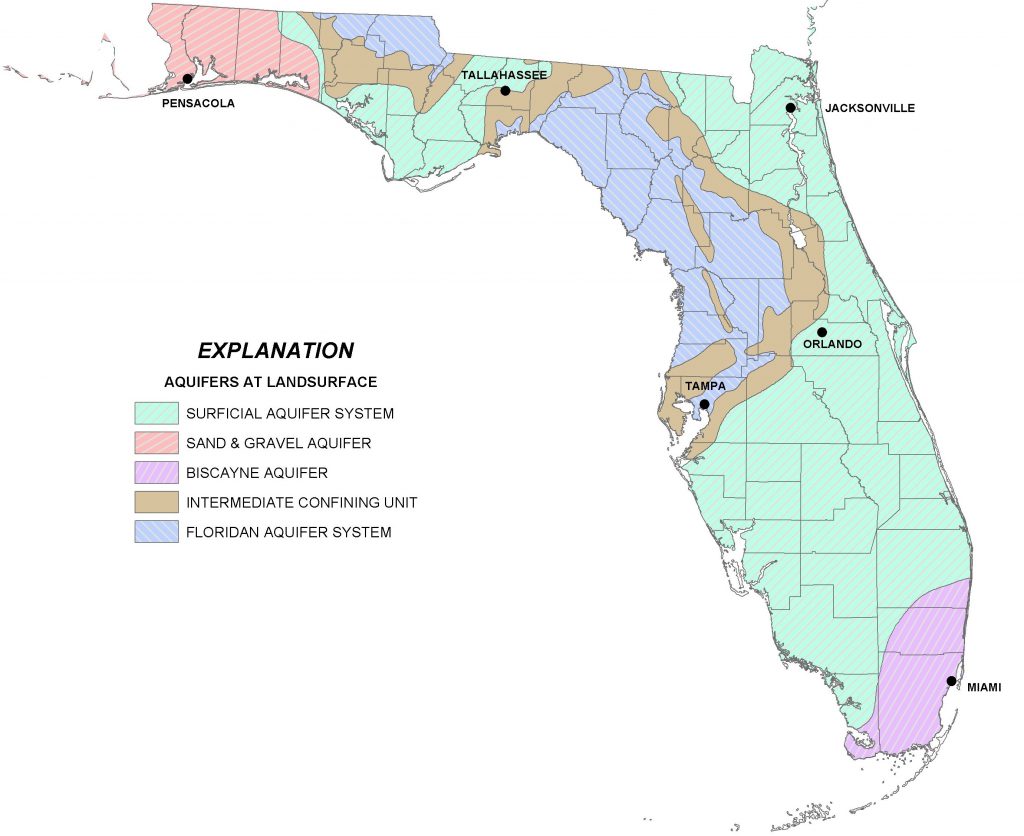

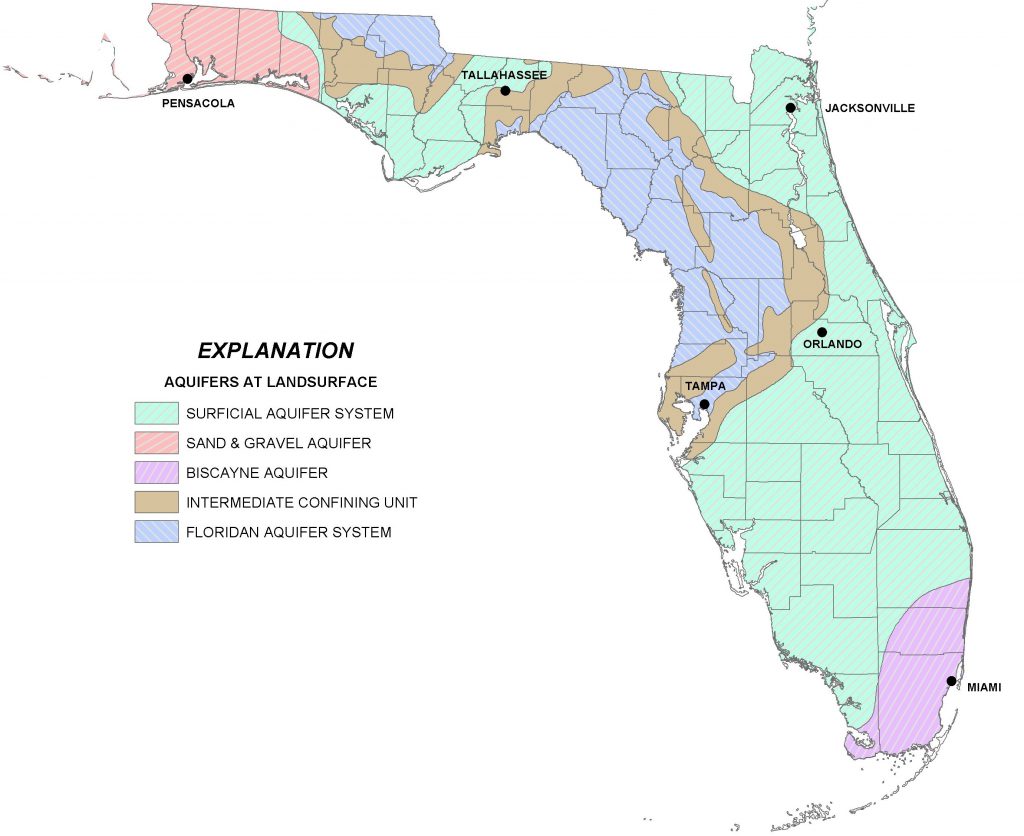

There are actually several major aquifer systems in Florida that lie on top of the Floridan Aquifer and are important sources of groundwater to local areas (Figure 2):

- The Sand and Gravel Aquifer in the far western panhandle is the main source of water for Santa Rosa and Escambia Counties. It is made up of of sand and gravel interbedded with layers of silt and clay.

- The Biscayne Aquifer supplies water to Dade and Broward Counties and southern Palm Beach County. A pipeline also transports water from this aquifer to the Florida Keys. The aquifer is made of permeable limestone and less permeable sand and sandstone.

- The Surficial Aquifer System (marked in green in the map in Figure 2) is the major source of drinking water in St. Johns, Flagler and Indian River counties, as well as Titusville and Palm Bay. It is typically shallow (less than 50 ft. thick) and is often referred to as a ‘water table’ aquifer, but in Indian River and St. Lucie Counties, it can be up to 400 ft. thick.

- Not included in Figure 2 is a fourth aquifer, the Intermediate Aquifer System in southwest Florida. It lies at a depth between the Surficial Aquifer System and the Floridan Aquifer. It is found south and east of Tampa, in Hillsborough and Polk counties and extends south through Collier County. It is the main source of water supply for Sarasota, Charlotte and Lee counties, where the underlying Floridan Aquifer is too salty to be potable.

Figure 2. A map of four major aquifer systems in the state of Florida at land surface. The Floridan Aquifer (in blue) underlies the entire state, but in areas north and east of Tampa it is found at the surface. The Surficial (green), Sand and Gravel (red), and Biscayne Aquifer (purple/pink) lie on top of the Floridan Aquifer. A confining unit (area in brown) consists of impermeable materials like thick layers of fine clay that prevent water from easily moving through it. Source: FDEP.

All of the aquifer systems in Florida are recharged by rainfall. In general, freshwater from deeper portions of the aquifer tends to have better water quality than surficial systems, since it is less susceptible to pollution from land surfaces. But, in areas where groundwater is excessively pumped or wells are drilled too deeply, saltwater intrusion occurs. This is where the underlying, denser saltwater replaces the pumped freshwater. Florida’s highly populated coastal areas are particularly susceptible to saltwater intrusion, and this is one of the main reasons that water conservation is a major priority in Florida.

More information about the Floridan Aquifer System and overlying aquifers can be found at the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (https://fldep.dep.state.fl.us/swapp/Aquifer.asp#P4) and in the UF EDIS Publication ‘Florida’s Water Reosurces’ by T. Borisova and T. Wade (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/fe757).

by Shep Eubanks | Nov 14, 2019

Eastern Wild Turkey Gobbler in Gadsden County – photo by Shep Eubanks UF/IFAS

The above picture of a strutting Eastern Wild Turkey is a sight that many hunters look forward to seeing every spring here in the panhandle of Florida. In order to manage wild turkeys and their habitat it is good to understand some basic facts about their biology.

Wild turkeys are considered a generalist species, meaning that they can eat a wide variety of foods, primarily seeds, insects, and vegetation. They prefer relatively open ground cover so that they can see well and easily move through their surroundings, but they aren’t picky about where they live as long as it provides them year-round groceries and safety. They are also a very adaptable species. Turkeys prefer low, moderately open herbaceous vegetation (less than three feet in height) that they can see through, or see over, and through which they can easily move in relatively close proximity to forested cover. Such open habitat conditions help them see and avoid predators and these areas will typically provide sufficient food in terms of edible plants, fruit, seeds, and insects.

Wild turkeys are considered, ecologically, to be a “prey species” and have evolved as a common food source for numerous animals—seems everything is trying to eat them. Turkey eggs, young (i.e.,poults), and adults are preyed on by such animals as bobcats, raccoons, skunks, opossum, fox , coyotes, armadillos, crows, owls, hawks, bald eagles, and a variety of snakes. Being prey to so many different animals has shaped the turkey’s biology and behavior. Turkeys experience high mortality rates and don’t live very long, on average, <2 years. They are particularly vulnerable during nesting and immediately after hatching. Because of this high mortality, reproduction is really important for turkey populations to replace the individuals that don’t survive from year to year. Wild turkeys have adapted to being a prey species in part, though, by having a high reproductive potential. Hens have the capacity to lay large clutches of eggs. If a nest is destroyed or disturbed, especially during the egg laying or early incubation period, the hen will often re-nest. Turkeys are also polygamous, with males capable of breeding multiple females, which further boosts their reproductive potential.

Turkey hen with poults foraging in a grassy field in Gadsden County – photo by Shep Eubanks UF/IFAS

Newly hatched turkeys, referred to as poults, need grassy, open areas so they can find an abundance of insects. Such areas are usually the most critical, and often the most lacking habitat in Florida. Under ideal conditions for turkeys, grassy openings would occupy approximately 25 percent of a turkey’s home range. Additionally, it is of equal importance to have such openings scattered throughout an area, varying in size from 1 to 20 acres such that they are small, or irregular in shape, to maximize the amount of adjacent escape cover (moderately dense vegetation or forested areas that can provide concealment from predators or other disturbances). Large, expansive openings (e.g., large pastures) without any escape cover are not as useful for turkeys since they generally will not venture more than 100 yards away from suitable cover.

Good habitat allows turkeys to SEE approaching danger and to MOVE unimpeded (either to move away from danger or simply to move freely while foraging without risk of ambush). In other words, good habitat provides the right vegetative structure. When thinking about habitat for turkeys, it’s good to always think from a turkey’s point of view….about 3 feet off the ground! Turkeys like open areas where they can see well and easily move.

Burning pine land in Gadsden County to improve wild turkey habitat – photo by Shep Eubanks UF/IFAS

One of the best management techniques to manage vegetation structure and composition is prescribed fire. Fire can be very destructive, but if properly applied, fire can be quite beneficial to wildlife and is one of the best things you can do for wild turkeys. When applied correctly, fire has many benefits. Some of the benefits of fire to turkeys and other wildlife include: control of hardwood by setting back woody shrubs and trees in the under story; improving vegetation height and structure; stimulating new herbaceous growth at ground level; stimulating flowering and increased fruit production in some plants; it improves nutritional value and increases palatability of vegetation. All of this leads to increased insect abundance and fewer parasites in the environment. Prescribed fire also has benefits for the landowner. Applied properly and regularly, prescribed fire will reduce risk of catastrophic wildfire which can destroy a timber stand. It reduces hardwood competition so favored pines grow faster and healthier; and reduces the risk of disease, particularly after a thinning or timber cut, by removing logging debris that would otherwise attract insects and disease-causing agents. It can also help control invasive species, and best of all it’s the least expensive option on a cost per acre basis.

Gobblers in pine stand after burn – Game Camera photo by Shep Eubanks

Another good practice is simply mowing or bush-hogging. Even in areas that aren’t super thick (such as around forest and field edges, or seasonal wetlands), mowing and bush-hogging alone, even without fire, are beneficial as they have much the same effect on the habitat as fire. Basically, you’re removing grown up vegetation and allowing light to reach the ground again. Within pine plantations, roads often provide some of the best, or only, turkey habitat simply because the surrounding vegetation becomes too dense so roads are used for feeding and moving throughout the area. In this regard, wide roads increase the amount of open habitat which provides lots of insects, seeds, and edible vegetation. They also reduce the opportunity for predators to ambush turkeys which can readily occur on narrow roads. Having wide roads is a good land management practice that lets roads dry-out quicker so that they can hold up to traffic better.

If you have pine dominated timber stands on your property, proper thinning is not only good for turkeys, but it’s good for your stand. Young pine stands, particularly those in sapling or early pole stages, are often too thick for wild turkeys, except as escape cover. They get so dense that they shade out everything underneath. They may produce some pine seeds when they get older, but for most of the year, there’s nothing to eat and nothing to attract turkeys to the area. For turkeys, thinning opens up the canopy and allows sunlight to reach the forest floor, which in turn stimulates plant growth of grasses, forbs and soft-mast producing shrubs.

If you have an interest in turkeys, do most management activities outside of the nesting season, which generally runs from the middle of March through June. From a practical standpoint that is not always possible, so on the positive side, if a nest is destroyed (whether by predators or management efforts), a hen will quite often re-nest. Also, the overall importance of management will often outweigh the loss of 1 or 2 nests. The time that turkey nests are at a premium is when a turkey population is low or just trying to get established into an area. In such cases every nest is valuable.

For more information consult with your local Extension Agent .

by Shep Eubanks | Sep 13, 2019

Common Salvinia Covering Farm pond in Gadsden County

Photo Credit – Shep Eubanks UF/IFAS Gadsden County Extension

Close up of common Salvinia

Photo Credit – Shep Eubanks UF/IFAS Gadsden County Extension

Aquatic weed problems are common in the panhandle of Florida. Common Salvinia (Salvinia minima) is a persistent invasive weed problem found in many ponds in Gadsden County. There are ten species of salvinia in the tropical Americas but none are native to Florida. They are actually floating ferns that measure about 3/4 inch in length. Typically it is found in still waters that contain high organic matter. It can be found free-floating or in the mud. The leaves are round to somewhat broadly elliptic, (0.4–1 in long), with the upper surface having 4-pronged hairs and the lower surface is hairy. It commonly occurs in freshwater ponds and swamps from the peninsula to the central panhandle of Florida.

Reproduction is by spores, or fragmentation of plants, and it can proliferate rapidly allowing it to be an aggressive invasive species. When these colonies cover the surface of a pond as pictured above they need to be controlled as the risk of oxygen depletion and fish kill is a possibility. If the pond is heavily infested with weeds, it may be possible (depending on the herbicide chosen) to treat the pond in sections and let each section decompose for about two weeks before treating another section. Aeration, particularly at night, for several days after treatment may help control the oxygen depletion.

Control measures include raking or seining, but remember that fragmentation propagates the plant. Grass carp will consume salvinia but are usually not effective for total control. Chemical control measures include :carfentrazone, diquat, fluridone, flumioxazin, glyphosate, imazamox, and penoxsulam.

For more information reference these IFAS publications:

Efficacy of Herbicide Active ingredients Against Aquatic Weeds

Common salvinia

For help with controlling Common salvinia consult with your local Extension Agent for weed control recommendations, as needed.

by Scott Jackson | Jun 21, 2019

Panama City Dive Center’s Island Diver pulls alongside of the El Dorado supporting the vessel deployment by Hondo Enterprises. Florida Fish and Wildlife crews also are pictured and assisted with the project from recovery through deployment. The 144 foot El Dorado reef is located 12 nautical miles south of St Andrew Pass at 29° 58.568 N, 85° 50.487 W. Photo by L. Scott Jackson.

In the past month, Bay County worked with fishing and diving groups as well as numerous volunteers to deploy two artificial reef projects; the El Dorado and the first of the Natural Resources Damage Assessment (NRDA) reefs.

These sites are in Florida waters but additional opportunities for red snapper fishing are available this year to anglers that book for hire charters with captains holding federal licenses. Federal licensed Gulf of Mexico charters started Red Snapper season June 1st and continue through August 1st. Recreational Red Snapper fishing for other vessels in State and Federal waters is June 11th – July 12th. So booking a federally licensed charter can add a few extra fish to your catch this year.

The conversion of the El Dorado from a storm impacted vessel to prized artificial reef is compelling. Hurricane Michael left the vessel aground in shallow waters. This was in a highly visible location close to Carl Grey Park and the Hathaway Bridge. The Bay County Board of County Commissioners (BOCC) acquired the El Dorado, January 14, 2019 through negotiations with vessel owner and agencies responsible for recovery of storm impacted vessels post Hurricane Michael.

The El Dorado was righted and stabilized, then transported to Panama City’s St Andrews Marina by Global Diving with support from the Coast Guard and Florida Fish and Wildlife. Hondo Enterprises, was awarded a contract to complete the preparation and deployment of the vessel for use as an artificial reef.

Reefing the El Dorado provides new recreational opportunities for our residents and tourists. The new reef delivers support for Bay County’s fishing and diving charters continuing to recover after Hurricane Michael. Several local dive charter captains assisted in the towing and sinking of the El Dorado.

The El Dorado was deployed approximately 12 nm south of St. Andrew Bay near the DuPont Bridge Spans May 2, 2019. Ocean depth in this area is 102 feet, meaning the deployed vessel is accessible to divers at 60 feet below the surface.

The Bay County Board of County Commissioners continues to invest in the county’s artificial reef program just as before Hurricane Michael. Additional reef projects are planned for 2019 – 2020 utilizing Natural Resources Damage Assessment (NRDA) and Resources and Ecosystems Sustainability, Tourist Opportunities, and Revived Economies of the Gulf Coast States Act (RESTORE Act) funds. These additional projects total over 1.3 million dollars utilizing fines as a result of the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill. Deployments will occur in state waters in sites located to both the east and west of St. Andrew Bay Pass.

Walter Marine deploys one of nine super reefs deployed in Bay County’s NRDA Phase I project located approximately 12 nautical miles southeast of the St. Andrew Pass. Each massive super reef weighs over 36,000 lbs and is 15 ft tall. Multiple modules deployed in tandem provides equivalent tonnage and structure similar to a medium to large sized scuttled vessel. Photo by Bob Cox, Mexico Beach Artificial Reef Association.

The first of these NRDA deployments for Bay County BOCC was completed May 21, 2019 in partnership with Mexico Beach Artificial Reef Association, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, and Florida Department of Environmental Protection using a $120,000 portion of the total funding. The deployment site in the Sherman Artificial Reef Permit Area is approximately 12 nm south east of St Andrew Bay Pass at a depth of 78 – 80ft.

| Patch Reef # |

Latitude |

Longitude |

| BC2018 Set 1

(6 Super Reefs and 4 Florida Specials) |

29° 55.384 N |

85° 40.202 W |

| BC2018 Set 2

(1 Super Reef and 4 Florida Specials) |

29° 55.384 N |

85° 39.739 W |

| BC2018 Set 3

(1 Super Reef and 4 Florida Specials) |

29° 55.384 N |

85° 39.273 W |

| BC2018 Set 4

(1 Super Reef and 4 Florida Specials) |

29° 55.384 N |

85° 38,787 W |

In 2014, Dr. Bill Huth from the University of West Florida, estimated in Bay County the total artificial reef related fishing and diving economic impact was 1,936 jobs, $131.98 million in economic output and provided $49.02 million in income. Bay County ranked #8 statewide in artificial reef jobs from fishing and diving. Bay County ranked #3 in scuba diving economy and scuba diving was 48.4 % of the total jobs related to artificial reefs. Dr. Huth also determine that large vessels were the preferred type of artificial reef for fishing and diving, with bridge spans and material the next most popular. Scuba diving and fishing on artificial reefs contributes significantly to the county’s economic health.

For more information and assistance, contact UF/IFAS Extension Bay County at 850-784-6105 or Bay@ifas.ufl.edu. Follow us on Facebook at http://faceboook.com/bayifas .

An Equal Opportunity Institution. UF/IFAS Extension, University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, Nick T. Place, Dean for UF/IFAS Extension. Single copies of UF/IFAS Extension publications (excluding 4-H and youth publications) are available free to Florida residents from county UF/IFAS Extension offices.

This article is also available through the the Panama City New Herald