by Sheila Dunning | Apr 14, 2018

Having just completed the Okaloosa/Walton Uplands Master Naturalist course, I would like to share information from the project that was presented by Ann Foley.

The Florida Torreya. Photo provided by Shelia Dunning

The Florida Torreya is the most endangered tree in North America, and perhaps the world! Less than 1% of the historical population survives. Unless something is done soon, it may disappear entirely! You can see them on public lands in Florida at Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve and beautiful Torreya State Park.

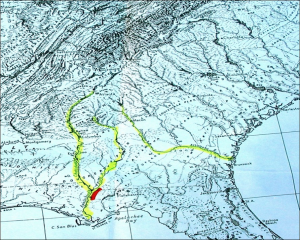

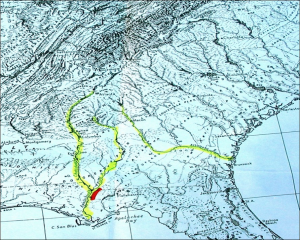

The Florida Torreya (Torreya taxifolia) is one of the oldest known tree species on earth; 160 million years old. It was originally an Appalachian Mountains ranged tree. As a result of our last “Ice Age” melt, retreating Icebergs pushed ground from the Northern Hemisphere, bringing the Florida Torreya and many other northern plant species with them.

The Florida Torreya was “left behind” in its current native pocket refuge, a short 40 mile stretch along the banks of the Apalachicola River. There were estimates of 600,000 to 1,000,000 of these trees in the 1800’s. Torreya State Park, named for this special tree, is currently home to about 600 of them. Barely thriving, this tree prefers a shady habitat with dark, moist, sandy loam of limestone origin which the park has to offer.

Hardy Bryan Croom, Botanist, discovered the tree in 1833, along the bluffs and ravines of Jackson, Liberty and Gadsen Counties, Florida and Decatur County in Georgia. He named it Florida Torreya (TOR-ee-uh), in honor of Dr. John Torrey, a renowned 18th century scientist.

Torreya trees are evergreen conifers, conically shaped, have whorled branches and stiff, sharp pointed, dark green needle-like leaves. Scientists noted the Torreya’s decline as far back as the 1950’s! Mature tree heights were once noted at 60 feet, but today’s trees are immature specimens of 3-6 feet, thought to be ‘root/stump sprouts.’

Known locally as “Stinking Cedar,” due to its strong smell when the leaves and cones are crushed, it was used for fence posts, cabinets, roof shingles, Christmas trees and riverboat fuel. Over-harvesting in the past and natural processes are taking a tremendous toll. Fungi are attacking weakened trees, causing the critically endangered species to die-off. Other declining factors include: drought, habitat loss, deer and loss of reproductive capability.

With federal and state protection, the Florida Torreya was listed as an endangered species in 1983. There is great concern for this ancient tree in scientific community and with citizen organizations. Efforts are underway to help bring this tree back from the edge of extinction!

Efforts include CRISPR gene editing technology research being done by the University of Florida Dept. of Forest Resources and Conservation- making the tree more resistant to disease. Torreya Guardians “rewilding and “assisted migration”. Reintroducing the tree to it’s former native range in the north near the Biltmore Estate in Asheville, NC, which has maintained a grove of Torreya trees and offspring since 1939 and supplying seeds for propagation from their healthy forest. Long before saving the earth became a global concern, Dr. Seuss (Theodor Seuss Geisel), spoke through his character the Lorax warning against urban progress and the danger it posed to the earth’s natural beauty. All of these groups, and many others, hope their efforts will collectively help bring this tree back from the brink!

by Sheila Dunning | Jan 19, 2018

The Florida Master Naturalist Program is an adult education University of Florida/IFAS Extension program. Training will benefit persons interested in learning more about Florida’s environment or wishing to increase their knowledge for use in education programs as volunteers, employees, ecotourism guides, and others.

The Florida Master Naturalist Program is an adult education University of Florida/IFAS Extension program. Training will benefit persons interested in learning more about Florida’s environment or wishing to increase their knowledge for use in education programs as volunteers, employees, ecotourism guides, and others.

Through classroom, field trip, and practical experience, each module provides instruction on the general ecology, habitats, vegetation types, wildlife, and conservation issues of Coastal, Freshwater and Upland systems. Additional special topics focus on Conservation Science, Environmental Interpretation, Habitat Evaluation, Wildlife Monitoring and Coastal Restoration. For more information go to: http://www.masternaturalist.ifas.ufl.edu/ Okaloosa and Walton Counties will be offering Upland Systems on Thursdays from February 15- March 22. Topics discussed include Hardwood Forests, Pinelands, Scrub, Dry Prairie, Rangelands and Urban Green Spaces. The program also addresses society’s role in uplands, develops naturalist interpretation skills, and discusses environmental ethics. Check the website for a Course Offering near you :http://conference.ifas.ufl.edu/fmnp/

by Les Harrison | Jan 5, 2018

St. Marks River Preserve State Park is still being developed, but open for native habitat enthusiast and those who enjoy this environment as nature established it.

Located along the banks of the St. Marks River’s headwaters, this park offers an extensive system of trails for hiking, horseback riding, and off-road bicycling. The existing road network in the park takes visitors through upland pine forests, hardwood thickets and natural plant communities along the northern banks of the river.

The St. Marks River is not navigable within the park boundaries. It is not conducive to canoeing or kayaking unless visitors are willing to accept long portages through thick undergrowth.

Most of the trails are dry and sandy, but plan for the low water crossings which some of the trails traverse. The rainy months of summer increase the prospects of water crossings.

This preserve is home to a wide variety of native fauna including black bear, deer, turkey and much more. Wildlife tracks frequently crisscross the park’s roads and trails.

At the northern end of the park two sections have had timber removed. One plot has been replanted with wiregrass seed which should germinate this year. Both areas have been planted with long-leafed pine seedlings.

This preserve offers avian aficionados the opportunity to witness nature at its finest as birds fill the air with their calls. A wide assortment of residential and migratory birds can be viewed in their natural habitat.

There are currently no amenities available at the park and it does not have restroom facilities. Additionally, visitors must bring in water for themselves or their horse.

There are no fees presently required to enjoy this gem of a park. Located east of Tallahassee, it is 3.5 miles east of W.W. Kelly Road on Tram Rd (Leon County Highway 259) almost to the Jefferson County line.

Adequate planning should be made to pack in and pack out all needed items for the day. The nearest convenience stores are located in Wacissa a few miles west of the park on Tram Road.

by Carrie Stevenson | Aug 25, 2017

Life on the Gulf Coast can be beautiful, but has its share of complications. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Life on the coast has tremendous benefits; steady sea breezes, gorgeous beaches, plentiful fishing and paddling opportunities. Nevertheless, there are definite downsides to living along it, too. Besides storms like Hurricane Harvey making semi-regular appearances, our proximity to the water can make us more vulnerable to flooding and waterborne hazards ranging from bacteria to jellyfish. One year-round problem for those living directly on a shoreline is erosion. Causes for shoreline erosion are wide-ranging; heavy boat traffic, foot traffic, storms, lack of vegetation with anchoring roots, and sea level rise.

Many homeowners experiencing loss of property due to erosion unwittingly contribute to it by installing seawalls. When incoming waves hit the hard surface of the wall, energy reflects back and moves down the coast. Often, an adjacent homeowner will experience increased erosion and bank scouring after a neighboring property installs a seawall. This will often lead that neighbor to install a seawall themselves, transferring the problem further.

Erosion can damage root systems of shoreline trees and grasses. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Currently, south Louisiana is experiencing significant coastal erosion and wetlands losses. The problem is compounded by several factors, including canals dredged by oil companies, which damage and break up large patches of the marsh. Subsidence, in which the land is literally sinking under the sea, is happening due to a reduced load of sediment coming down the Mississippi River. Sea level rise has contributed to erosion, and most recently, an invasive insect has caused large-scale death of over 100,000 acres of Roseau cane (Phragmites australis). Add the residual impacts from the oil spill, and you can understand the complexity of the situation.

Luckily, there are ways to address coastal erosion, on both the small and large scale. On Gulf and Atlantic beaches, numerous coastal communities have invested millions in beach renourishment, in which offshore sand is barged to the coast to lengthen and deepen beaches. This practice, while common, can be controversial because of the cost and risk of beaches washing out during storms and regular tides. However, as long as tourism is the #1 economic driver in the state, the return on investment seems to be worth it.

On quieter waters like bays and bayous, living shorelines have “taken root” as a popular method of restoring property and stabilizing shorelines. This involves planting marsh grasses along a sandy shore, often with oyster or rock breakwaters placed waterward to slow down wave energy, and allow newly planted grasses to take root.

Locally in Bayou Grande, a group of neighbors were experiencing shoreline erosion. Over a span of 50 years, the property owners used a patchwork of legally installed seawalls, bulkheads, rip rap piles, private boat ramps, piers, mooring poles and just about anything else one can imagine, to reduce the problem. Over time, the seawalls and bulkheads failed, lowering the property value of the very property they were meant to protect and increasing noticeable physical damage to the adjacent properties.”

Project Greenshores is a large-scale living shoreline project in Pensacola. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

In 2011, a group of neighboring property owners along the bayou decided to take action. After considering many repair options, the neighbors decided to pursue a living shoreline based on aesthetics, long-term viability, installation cost, maintenance cost, storm damage mitigation and feasibility of installation. By 2017, the living shoreline was constructed. Oyster shell piles were placed to slow down wave energy as it approached the transition zone from the long fetch across the bayou, while uplands damage was repaired and native marsh grasses and uplands plants were restored to slow down freshwater as it flowed towards the bayou. Sand is now accruing as opposed to eroding along the shoreline. Wading shorebirds are now a constant companion and live oysters are appearing along the entire 1,200-foot length. Additionally the living shoreline solution provided access to resources, volunteer help, and property owner sweat equity opportunities that otherwise would have been unavailable. An attribute that has surprisingly appeared – waterfront property owners are now able to keep their nicely manicured lawns down to within 30 feet of the water’s edge. At that point, the landscape immediately switches back to native marsh plants, which creates a quite robust and attractive intersection. (Text and information courtesy Charles Lurton).

Successes like these all over the state have led the Florida Master Naturalist Program to offer a new special topics course on “Coastal Shoreline Restoration” which provides training in the restoration of living shorelines, oyster reefs, mangroves, and salt marsh, with focus on ecology, benefits, methods, and monitoring techniques. Keep an eye out for this course being offered near you. If you are curious about living shorelines and want to know more, reach out to the Florida Department of Environmental Protection Ecosystem Restoration section for help and read through this online document.

by Rick O'Connor | Aug 11, 2017

Our first POL program will happen this week – August 17 – at the Navarre Beach snorkel reef, and is sold out! We are glad you all are interested in these programs.

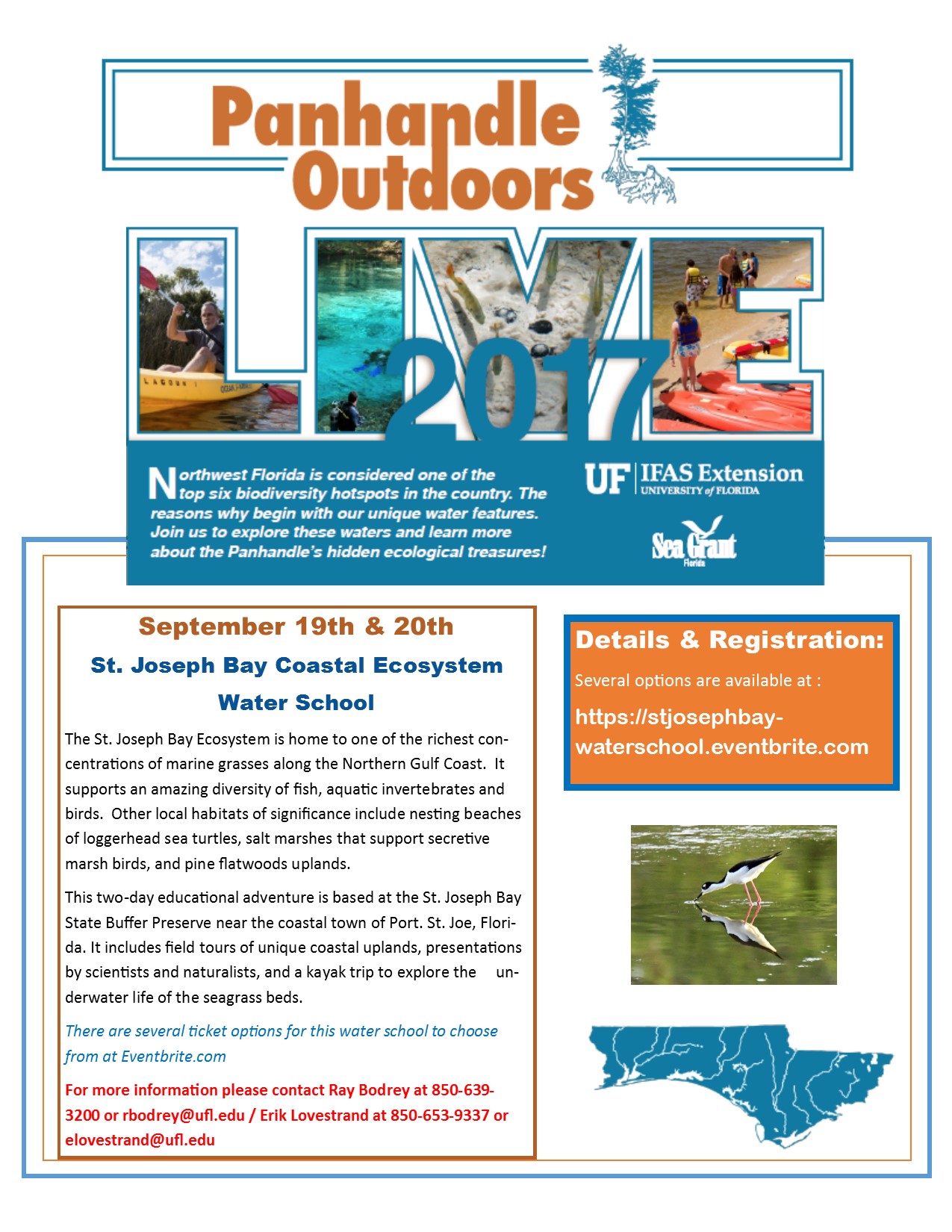

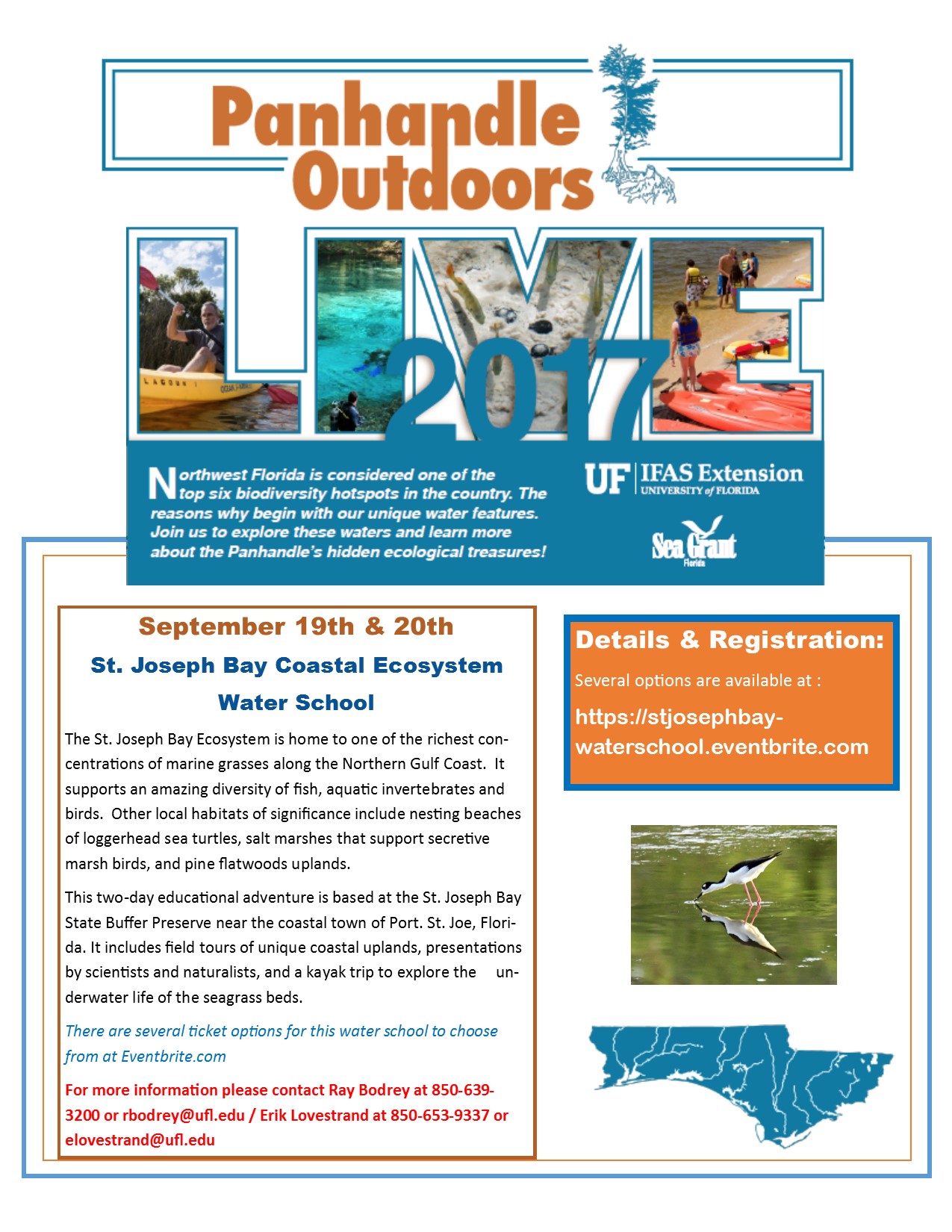

Well! We have another one for you. The Natural Resource Extension Agents from UF IFAS Extension will be holding a two-day water school at St. Joseph Bay. Participants will learn all about the coastal ecosystems surrounding St. Joe Bay in the classroom, snorkeling, and kayaking. Kayaks and overnight accommodations are available for those interested. This water school will be September 19-20. For more information contact Extension Agent Ray Bodrey in Gulf County or Erik Lovestrand in Franklin. Information and registration can be found at https://stjosephbay-waterschool.eventbrite.com.

by Scott Jackson | Jul 14, 2017

The St Andrew Bay pass jetty is more like a close family friend than a collection of granite boulders. The rocks protect the inlet ensuring the vital connections of commerce and recreation. One of the treasured spots along the jetty is known locally as the “kiddie pool”, which is accessible from St Andrew’s State Park. There are similar snorkeling opportunities throughout northwest Florida. Jetties provide an opportunity to explore hard substrate or rocky marine ecosystems. These rocks are home to a variety of colorful sub-tropical and migrating tropical fish.

Snorkelers and divers who visit are likely to see a variety fish like sergeant majors, blennies, surgeon and doctor fish, just to name a few. Photo by L Scott Jackson.

Exploring a jetty is more like a sea-safari adventure than an experience in a real swimming pool – it is a natural place full of potential challenges that first time visitors need to prepare to encounter.

Divers and snorkelers are required to carry dive flags when venturing beyond designated swimming areas. These flags notify boaters that people are in the water. Brightly colored snorkel vests are not only good safety gear but they help you rest in the water without standing on rocks which are covered in barnacles and sometimes spiny sea urchins.

According to the Florida Department of Health, most sea urchin species are not toxic but some Florida species like the Long Spined Sea Urchin have sharp spines can cause puncture injuries and have venom that can cause some stinging. Swim and step carefully when snorkeling as they usually are attached to rocks, both on the bottom and along jetty ledges. Photo by L Scott Jackson

Dive booties also help protect your feet. I found out the hard way! A couple of years ago my foot hit against a sea urchin puncturing my heel. The open back of my dive fin did not provide any protection resulting in a trip to the urgent care doctor. My daughter later teased it was an “urchin care” doctor! Sea urchin spines are brittle and difficult to remove, even for a doctor. Lesson Learned: “Prevention is the best medicine”.

After a couple of weeks of limping around and a course of antibiotics, I recovered ready to return one of my favorite watery places – a little wiser and more prepared. I now bring a small first aid kit, just in-case, to help take care of small scrapes, cuts, and other minor injuries.

Gloves are recommended to protect hands from barnacle cuts and scrapes. Shirts like a surfing rash guard or those made from soft material help keep your body temperature warm on long snorkel excursions. Along with sunscreen, shirts also protect against sunburn.

There’s opportunity to see marine life from the time you enter the water with depths for beginning snorkelers at just a few feet deep. Some SCUBA divers also use the jetty for their initial training. Most underwater explorers are instantly hooked, and return for many years to come. Photo by L Scott Jackson

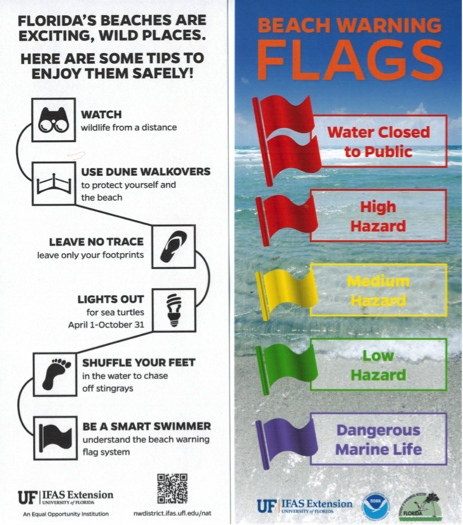

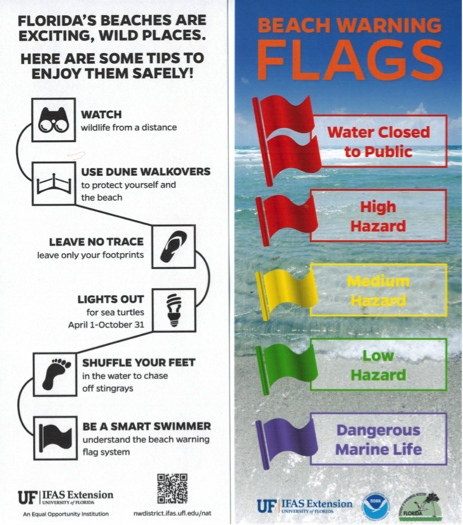

Finally, know the swimming abilities of yourself and your guests, especially when venturing to deeper areas. It’s good to have a dive buddy even when snorkeling. Pair up and watch out for each other. Be aware that currents and seas can change dramatically during the day. Know and obey the flag system. Double Red Flag means no entry into the water. Purple flags indicate presence of dangerous marine life like jellyfish, rays, and rarely even sharks. Local lifeguards and other beach authorities can provide specific details and up to date safety information.

Follow these beach safety tips for helping your family enjoy the beach while protecting coastal wildlife.

An Equal Opportunity Institution. UF/IFAS Extension, University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, Nick T. Place, dean for UF/IFAS Extension. Single copies of UF/IFAS Extension publications (excluding 4-H and youth publications) are available free to Florida residents from county UF/IFAS Extension offices.