by Rick O'Connor | Apr 29, 2022

I recently saw a news clip about a new Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation (FWC) ruling for shrimpers. I was interested in this new ruling but also asked the question – “Where did all of the shrimpers go?”

What I mean by this is that when I was young there were shrimp boats on Pensacola Bay every evening. They seemed to trawl one side of the Pensacola Bay Bridge or the other, but you could see the lights on the decks of each trawler and there were many, looking like front porch lights of a small community, all over the bay. In the morning they would head towards the seawall along both sides of Palafox Street near the old Pensacola Municipal Auditorium and sell from the boats. We made frequent trips there.

Then the boats stopped coming to the docks…

And the Municipal Auditorium is now gone also…

Shrimping in the Gulf of Mexico.

Photo: NOAA

The focus turned to the docks near Joe Patti’s. Joe Patti’s, American, and Allen Williams Seafood companies were places we would frequent to purchase shrimp when they came in. Then those slowly disappeared with only Joe Patti’s remaining open to the public. The shrimp boats still come to the docks of Allen Williams, but in fewer numbers and the shrimp began to go through Joe Patti’s, Maria’s, Perdido and other seafood markets. Now the lights on the bay at night are few. Actually, I rarely see them anymore. Where did they go?

As you look at the commercial landings of shrimp since 1980 you see some interesting trends.

First, understand that commercial landings mean this is where the shrimpers “land” their catch, not where they caught it.

Second, that brown shrimp (bay shrimp) are BY FAR the most landed species in Escambia County. Comparing brown shrimp to white (also called Gulf shrimp), rock shrimp, and royal reds, there was a total of 13,372,791 lbs. of brown shrimp landed between 1984 and 2019. For the others white shrimp was 255,587 lbs., royal reds 95,920 lbs., and rock shrimp 78,817 lbs. You could also say the same for effort. Between 1984-2019 there were 31,935 trips for brown shrimp, 904 for white shrimp, 143 for rock shrimp, and only 19 for royal reds. So, brown shrimp are king for commercial landings here.

Third, there were 1000 or more trips per year for brown shrimp until 2002. That year it dropped to 835. In 2003 that was cut in half to 453 and the trend continued to decline. Between 2017-2019 there were less than 100 trips each year. There is a similar pattern for white shrimp. Prior to 2002 the number of trips for white shrimp were in the double digits, occasionally in the triple, each year. In 2002 it dropped from 38 to 7 per year and never recovered. Though royal reds and rock shrimp were never big players in local landings, between 2010 and 2019 there was only one trip for rock shrimp and no trips were logged for royal reds. What happened?

The famous Gulf Coast shrimp.

Photo: Mississippi State University

To try and find answers I reached out to a couple of my seafood contacts. Teresa and Bob Pitts are from the Perdido Key area and have been involved with commercial fishing most of their lives. Teresa currently manages Perdido Seafood and Bob works with the National Park Service but they both have strong ties to this industry. Jimbo Meador is a lifelong resident of Mobile Bay and has been involved in several industries including seafood over there. Jimbo recently retired from being nature tour operator in the Mobile Delta but still has ties to the seafood business and a wealth of knowledge. Dr. Andrew Ropicki is an economist with Florida Sea Grant and the University of Florida who focuses on seafood and other marine related topics. I had a conversation with all, and comments were made that helped connect some the dots.

In 1995 the state imposed a net ban on all entanglement nets 500 ft2 or larger from state waters. This obviously would have included Pensacola Bay. I know the shrimpers were opposed to this amendment. They were very visible and vocal about it. Once passed it would make sense they would move their operations from Pensacola Bay to Alabama, or federal waters offshore, so they could continue to use their standard sized otter trawls. Honestly, I do not remember which year the deck lights of the shrimp boats began to disappear, but I would guess many did leave when this law was passed. However, this did not impact the number of landings, they continued to bring shrimp here.

Otter trawl is correct name for what folks call a shrimp net. In 1995 any entanglement net over 500 square feet were banned in Florida waters.

Prior to 1995 landings of brown shrimp ranged from 1114 to 2523 a year with an average of 1760. Between 1995 and 2000 the range was from 1134 to 1816 with an average of 1442. A slight drop, but nothing significant. If they were shrimping somewhere else, they were still landing in Escambia County. I recently had a conversation about this with Bob Jackson, one of my citizen science volunteers. He moved here around 2000 and remembered shrimp boats still being on the bay at that time. Some may have moved due to the net ban, but not all. The shrimping was still on.

In 2002 the landings did take a significant drop – 835 landings that year. The first time they were below 1000/year since the records were kept in 1984. In 2003 they dropped further to 453 and the decline has continued ever since. Where were they landing their shrimp? Were they still shrimping? I do not know.

Jimbo asked the question “when did the surge of foreign imports begin?” Good question. We know now that at least 80% of the seafood consumed in Florida is imported. When did this move from local to import make this big swing? Dr. Ropicki found a world shrimp production graph that showed 2003 as a year with a big increase in aquaculture shrimp. Aquaculture accounted for 28% of global shrimp production in 2000 and 55% in 2010, and that is with wild caught shrimp increasing slightly. The big swing towards aquaculture in 2003 closely mirrors the decline in local wild harvest landings in 2002. This certainly could be a piece of the puzzle.

Seafood markets offer local products as well as those from around the world.

Photo: Florida Sea Grant

Did this competition with imports create less effort on the part of local shrimpers?

It certainly had some impact. All of my contacts indicated that the price difference between imported and local seafood made it much more difficult to do business. Add to this the rise in cost of fuel, insurance, and regulations to the industry, some captains did sell their boats and found another line of work.

Looking at the fuel story, Dr. Ropicki found a chart published by the U.S. Energy Information Administration. The chart shows how Gulf coast #2 diesel prices have changed since 1995. Basically from 1995 to 2021 they tripled (200% increase) while general inflation was only about a 75% increase. As many know it is a very fuel intensive industry.

In 2004 Hurricane Ivan hit our area and that certainly would have caused a decline in landings due to damage to boats and docks. The number of landings that year was 388. Between 2004 and 2010 landings steadily declined from 388 to 155/year. The days of 1000+ landings seemed to be over. Many shrimpers lost their boats during the storm and just found another line of work.

Hurricanes are one reason some shrimpers have left the business.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

To add fuel to the fire, in 2010 the Deepwater Horizon oil spill occurred. That year there were only 85 landings in Escambia County, the first year we had less than 100. But we understand why – no shrimping occurred with oil in the water. Many shrimpers still in the business were hired to help clean up the spill, and did make money doing it, but they were not landing shrimp.

The BP Oil Spill was one of the worst natural disasters in our country’s history.

Photo: Gulf Sea Grant

In 2011 landings returned to 187 for the year and even up to 235 in 2012, but since there has been again a steady decline. In 2017 we went below 100 landings again. Between 2017 and 2019 the landings in Escambia County were 66, 53, and 70 respectively – the lowest ever. FAR below the 1000-2000 landings in the 1980s and 1990s.

Further discussion with my contacts yielded another trend. Commercial fishing historically was a family venture. Families worked the boats and sons took over the business from their fathers. That seems to have stopped. One shrimper who did talk to me said at one point we had between 40-50 boats in our fleet, now there are 11 and their kids want nothing to do with the business. As one of the contacts mentioned “they would rather work with their brains than their backs”.

Commercial seafood in Pensacola has a long history.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

In Alabama many families actually lived on their boats and the entire family would go out when the shrimping was on. I was told they do not see this anymore. There are still some bay shrimpers who sell their catch along the Hwy 90 causeway crossing Mobile Bay, and they seem to be doing well, but there are fewer of them. I was also told that many of the Gulf shrimp boats in Alabama have been sitting idle at dock for several years, many are up for sale, and it has been primarily foreign businesses buying them. There were once 120 Gulf shrimp boats in the fleet at Bon Secour Seafood, now there is one. I recently heard a Pensacola shrimper who made port in Bayou Chico – just sold his boat this year.

Dr. Ropicki also shared data on price for shrimp. Could this play a role in this story?

Most commercial seafood products have seen an increase in purchase price at the dock, but not shrimp. Checking the state records for price/pound for brown shrimp in Escambia County found some interesting trends. Between 1985 and 2020 the average price paid for their harvest was between $1.50 and $2.00 a pound. At least once each decade the price went to $2.00 or more per pound – but only ONCE each decade. In that time the number of years where the price dropped BELOW $1.50 per year steadily increased. Between 1985-89 the price dropped below $1.50 only once. Between 1990-1999 it never dropped below. Between 2000-2009 it dropped below $1.50/lb. six times. This happened again between 2010-2019 – six times. In 2006 local shrimpers only got $1.01/pound for the work – the lowest in this data set. If you look at the average price a shrimper received for their brown shrimp harvest by decade you see…

1985-89 – $1.82

1990-1999 – $1.78

2000-2009 – $1.58

2010-2019 – $1.54

A steady decline over time. Along with storms, regulations, fuel costs, lack of labor, and competition with imports, you can add price to the “soup of problems”.

I was curious if a similar scenario was playing out in Apalachicola. Apalach is known for their oysters, but there is a sizable shrimping industry there as well – it’s a seafood town. I asked our Sea Grant Agent over there, Erik Lovestrand, about similar trends. He did not have any data but was reasonably certain that the number of boats working out of their docks had significantly declined over the years.

Known for their oysters, Apalachicola is also a shrimping town.

I decided to take a look at the landing numbers for Apalachicola. I looked at brown shrimp.

Between 1985-1989 they averaged 909 landings – less effort for this species than in Escambia County.

Between 1990-1999 there averaged 1546 landings a year.

Between 2000-2009 the average was 382.

And between 2010-2020 it was 68.

The pattern looks similar albeit the number of landings was brown shrimp were less in Apalachicola. However, I did see another interesting difference – price paid per pound. In Escambia over this time the average price was $1.66/pound. It only went to $2.00/pound once decade and began to drop below $1.50 frequently over the last 20 years. However, in Apalachicola the average price was $2.00 rarely going below that and even reached $3.32/pound in 2014. They pay more for brown shrimp in Apalach. I am not sure if that impacted landings locally. The data suggests that it did not, but it is interesting.

And then, another thought came to mind. From the Big Bend of Florida south to Key West pink shrimp, not browns, are the target species. What did the pink shrimp landings look like? Did Escambia make a switch?

The results were interesting. Between 1985-2021 the landings of pink shrimp in Apalachicola occurred every year. The total number of landings was 6431 and averaged 174/year. The price was good, ranging from $1.80 to $3.23/pound, the average price was $2.39. The number of trips per year never broke 500 and the trend on landings shows a decline over this time period. But the price was decent for those who chose to target this shrimp.

In Escambia County the effort was low. They did not continuously land pink shrimp each year, but rather over short periods. Landings occurred between 1986-1991. Then nothing until 1997. Then another short period from 2000-2003. Then nothing again until 2014, which ran until 2020. Other than in 2000, the number of trips for pink shrimp were less than 10 a year (they were 10 in 2000). The average number of trips since 1986 was 4/year – less than Apalachicola and much less that the brown shrimp harvest here.

However, the price per pound was much higher for pink shrimp in Escambia. It ran from $1.59 to $5.00/pound! The average price was $2.77 (more than what they were paying in Apalachicola). Though Escambia landings were not big for pink shrimp, it was certainly more profitable than brown shrimp.

Pink shrimp are very popular.

All of the above played play a role in the decline of the local shrimping industry. However, if you visit a local seafood market you will find shrimp. Some is still local, local landings may be down, but they have not stopped. Some are local in the since they were harvested elsewhere in the Gulf of Mexico and trucked to us. But as we mentioned, cheaper imports are easier to get. So, it does not seem we are going to run out of shrimp, just out of shrimpers. For some it is unnerving that we will be dependent on other countries for our seafood, but we will have seafood.

Which brings up the topic of aquaculture. This is for another article. Until then, we do encourage you to enjoy seafood, it is a healthy source of protein. We will see where the local industry heads in the next decade, but you can still get shrimp, and I have seen nice looking ones in there. Enjoy them.

A rare site – a shrimping landing its catch in Pensacola Bay in 2022.

Note: After completing this article I had a meeting in Bayou LaBatre AL. I was told that shrimping industry there was hanging on… barely. Also, the high school teacher I met with said he was not aware of one kid in the school who planned to become a shrimper… this is in Bayou LaBatre Alabama.

Special thanks to

Bob and Teresa Pitts – Perdido Bay Seafood

Jimbo Meador

Dr. Andrew Ropicki – University of Florida / Florida Sea Grant

Erik Lovestrand – UF IFAS Extension / Florida Sea Grant / Franklin County

Bob Jackson

by Laura Tiu | Jan 27, 2022

February is American Heart Month and when I think of heart, my thoughts turn to seafood. Perhaps that is unusual, but I love seafood and the fact that the American Heart Association recommends 1 to 2 seafood meals a week fits right into my gastronomic plans. More seafood on your table can improve your overall health and help fight off infections.

During the recent pandemic, an increase in home cooking has resulted in a rise in seafood consumption. Consumers rediscovered frozen and canned fish, a trend that continues today. Canned tuna and fish stick consumption rose as home cooks perfected their tuna melts and fish sandwiches. Home chefs throwing fish steaks, aluminum wrapped fillets, shrimp, and even oysters on the grill have raised the bar on home-cooked meals.

Other new trends on the horizon are more innovative. How do Atlantic salmon hot dogs sound? High-end canned and jarred seafood, think canned smoked oysters, are gaining in popularity as well as being quick and easy to prepare. Nose to tail is another trend that promotes maximum utilization of the whole seafood product. Cooking fish whole or tanning fish skins for an upscale leather are new ways to enjoy seafood. Want to try something new? Sea vegetables, including kelp and other seaweed are taking the culinary world by storm because of their great taste and nutritional benefits.

Let us not forget about our furry friends. Sustainable seafood-based pet treats are gaining quite a bit of market share. Seafood has one of the lowest environmental footprints of any protein, and as such makes a great, healthy, sustainable snack for fido.

Sustainable seafood, both wild and farm-raised, is an option that is good for your heart and good for the planet. Buying sustainably harvested or raised seafood is one way you can do your part to protect the ocean and ensure plentiful seafood for the future. Make a resolution to try a new product, recipe, or cooking method during this month to celebrate a healthy heart.

Cooked red snapper (Photo credit: L. Tiu)

by Laura Tiu | Nov 19, 2021

There are a lot of good oyster quotes. One I remember from childhood is the saying to only eat oysters in months with the letter “r,” basically September to April. I believe this originated when all oysters came from the wild. This was a way to avoid the hot months that may have led to a watery oyster, or even food poisoning. Today, with the rise of oyster aquaculture and refrigeration, oysters can be enjoyed year-round.

The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission recently made the tough decision to shut down wild oyster harvesting in Apalachicola, FL for up to five years in response to a struggling bay oyster population threatened by water flow issues and overharvesting. This was devastating news to an area that historically produced 90% of the state’s oysters and 10% of the nation’s. On the bright side, oyster aquaculture has been steadily growing in the area and is working hard to fill some of the gap.

A team of Florida Sea Grant Agents recently made a visit to Apalachicola to learn more about this historic oyster town and how the industry is adapting. Our first stop was Water Street Seafood, the Florida Panhandle’s largest seafood distributer. Water Street provides a wide diversity of both fresh and frozen seafood, including oysters, delivering daily in northwest Florida and shipping worldwide. We visited their oyster processing facility where we saw mesh bags of oysters brought in from Louisiana and Texas. The oysters, both farmed and wild caught, are carefully cleaned and sorted, with some going to the live, halfshell, restaurant market and some shucked onsite for the shucked market.

Next, we visited one of the many new oyster aquaculture farms in the area. Oysters farms are permitted by the state and are located in waters that have been carefully evaluated for their suitability for oyster production. Small plots are leased to the farmer allowing off-bottom production in mesh bags teathered with anchors in the shallow, productive bay waters. Oyster farmers tend to their crop by turning the bags regularly to reduce fouling of the oyster shell, and sorting by size as the oyster grows. Oysters take between eight to eighteen months to reach a harvest size.

Given the increasing demand for oysters by tourists and locals, we can thank aquaculture for keeping these tasty gems on our plates. If you are lucky enough to find some locally raised oysters on the menu, take the opportunity to try something new and support a local farmer.

An oyster farmer visiting his lease to monitor his crop. (credit: L. Tiu)

T

Fresh live oysters from an Apalachicola Oyster Farm (credit: L. Tiu)

Oyster bag holding cooler at Water Street Seafood with green bags holding wild caught oysters and purple bags holding farm raised oysters. (credit: L. Tiu)

by Erik Lovestrand | Mar 11, 2021

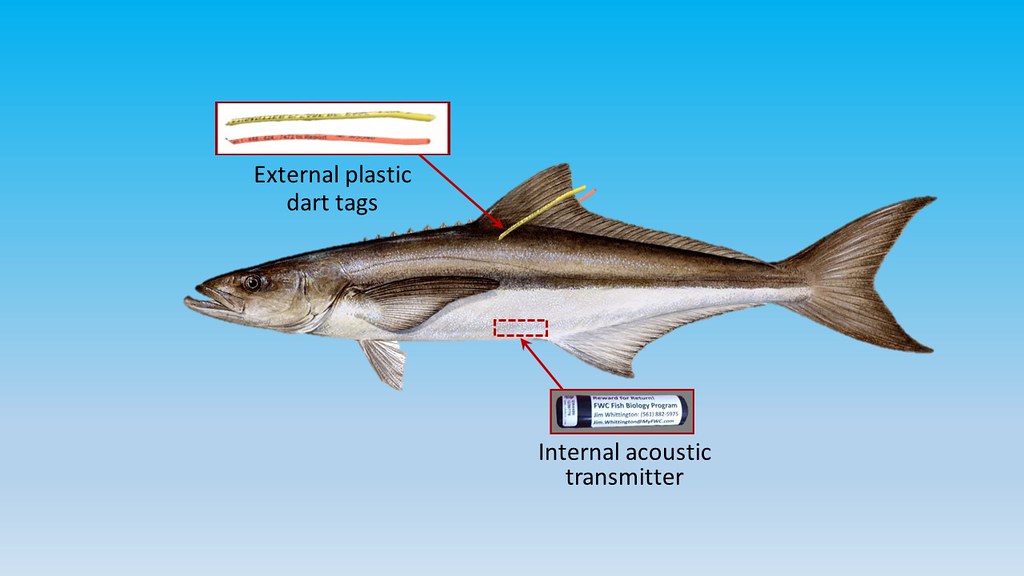

Cobia Researchers use Transmitters as well as Tags to Gather Data on Migratory Patterns

I must admit to having very limited personal experience with Cobia, having caught one sub-legal fish to-date. However, that does not diminish my fascination with the fish, particularly since I ran across a 2019 report from the Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission titled “Management Profile for Gulf of Mexico Cobia.” This 182-page report is definitely not a quick read and I have thus far only scratched the surface by digging into a few chapters that caught my interest. Nevertheless, it is so full of detailed life history, biology and everything else “Cobia” that it is definitely worth a look. This posting will highlight some of the fascinating aspects of Cobia and why the species is so highly prized by so many people.

Cobia (Rachycentron canadum) are the sole species in the fish family Rachycentridae. They occur worldwide in most tropical and subtropical oceans but in Florida waters, we actually have two different groups. The Atlantic stock ranges along the Eastern U.S. from Florida to New York and the Gulf stock ranges From Florida to Texas. The Florida Keys appear to be a mixing zone of sorts where Cobia from both stocks go in the winter. As waters warm in the spring, these fish head northward up the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of Florida. The Northern Gulf coast is especially important as a spawning ground for the Gulf stock. There may even be some sub-populations within the Gulf stock, as tagged fish from the Texas coast were rarely caught going eastward. There also appears to be a group that overwinters in the offshore waters of the Northern Gulf, not making the annual trip to the Keys. My brief summary here regarding seasonal movement is most assuredly an over-simplification and scientists agree more recapture data is needed to understand various Cobia stock movements and boundaries.

Worldwide, the practice of Cobia aquaculture has exploded since the early 2000’s, with China taking the lead on production. Most operations complete their grow-out to market size in ponds or pens in nearshore waters. Due to their incredible growth rate, Cobia are an exceptional candidate for aquaculture. In the wild, fish can reach weights of 17 pounds and lengths of 23 inches in their first year. Aquaculture-raised fish tend to be shorter but heavier, comparatively. The U.S. is currently exploring rules for offshore aquaculture practices and cobia is a prime candidate for establishing this industry domestically.

Spawning takes place in the Northern Gulf from April through September. Male Cobia will reach sexual maturity at an amazing 1-2 years and females within 2-3 years. At maturity, they are able to spawn every 4-6 days throughout the spawning season. This prolific nature supports an average annual commercial harvest in the Gulf and East Florida of around 160,000 pounds. This is dwarfed by the recreational fishery, with 500,000 to 1,000,000 pounds harvested annually from the same region.

One of the Cobia’s unique features is that they are strongly attracted to structure, even if it is mobile. They are known to shadow large rays, sharks, whales, tarpon, and even sea turtles. This habit also makes them vulnerable to being caught around human-made FADs (Fish Aggregating Devices). Most large Cobia tournaments have banned the use of FADs during their events to recapture a more sporting aspect of Cobia fishing.

To wrap this up I’ll briefly recount an exciting, non-fish-catching, Cobia experience. My son and I were in about 35 feet of water off the Wakulla County coastline fishing near an old wreck. Nothing much was happening when I noticed a short fin breaking the water briefly, about 20 yards behind a bobber we had cast out with a dead pinfish under it. I had not seen this before and was unaware of what was about to happen. When the fish ate that bait and came tight on the line the rod luckily hung up on something in the bottom of the boat. As the reel’s drag system screamed, a Cobia that I gauged to be 4-5 feet long jumped clear out of the water about 40 yards from us. Needless to say, by the time we gained control of the rod it was too late; a heartbreaking missed opportunity. Every time we have been fishing since then, I just can’t stop looking for that short, pointed fin slicing towards one of our baits.

by Laura Tiu | Feb 12, 2021

Cooked red snapper (Photo credit: L. Tiu)

It’s February and for many, our thoughts turn to romance and other things that make the heart happy, like seafood! There is a strong “love” connection between consuming seafood and heart health. Fish and shellfish are low in saturated fat, high in protein and fairly easy and quick to cook. But seafood has a secret weapon in the battle for our hearts as it is considered a good source of omega-3 fatty acids. The health effects of omega-3 fatty acids have been extensively investigated, and it appears that marine fish oil lowers triglycerides, boosts HDL cholesterol, provides other cardiovascular benefits, fights inflammation, and reduces blood clot formation.

The current recommendation from the American Heart Association is 1 to 2 seafood meals, 8 ounces or more, per week be consumed to reduce the risk of congestive heart failure, coronary heart disease, ischemic stroke, and sudden cardiac death, especially when seafood replaces the intake of less healthy foods. This translates into 250 to 500 mg of omega-3 per day or 1750 to 3500 mg per week. For the past 30 years, Americans’ weekly consumption of seafood has hovered around 5 oz per week, with only 10% to 20% of U.S. consumers meeting the 8 ounces minimal federal dietary guideline.

Historically, attention has focused on wild, cold-water, fatty fish like salmon, tuna, mackerel, and sardines as sources of the most omega-3 fatty acids. However, in this case variety is a key. With a growing number of aquaculture fish and shellfish on the market it is important to note that recent studies show for some species of salmon or trout, omega-3 levels are higher in farm-raised species, due to their overall higher fat content. In other good news, many of our local Gulf of Mexico species have been shown to contain good amounts as well. This information means that fishermen and women can eat home-caught fish to get the needed omega-3 fatty acids. Gulf fish are also an excellent source of protein and other nutrients. The following Table contains the omega-3 fatty acid content of some of the most frequently consumed fish and shellfish species in the U.S. So do your heart a favor and start feeding it right.

Omega-3 Content of Frequently Consumed Seafood Products

SEAFOOD PRODUCT

|

|

OMEGA-3s PER 3 OUNCE COOKED PORTION

|

| Herring, Wild (Atlantic & Pacific) |

♥♥♥♥♥ |

>1,500 milligrams |

| Salmon, Farmed (Atlantic) |

♥♥♥♥♥ |

| Salmon, Wild (King) |

♥♥♥♥♥ |

| Mackerel, Wild (Pacific & Jack) |

♥♥♥♥♥ |

SEAFOOD PRODUCT

|

|

OMEGA-3s PER 3 OUNCE COOKED PORTION

|

| Salmon, Wild (Sockeye, Coho, Chum & Pink) |

♥♥♥ |

500 to 1,000 milligrams |

| Sardines, Canned |

♥♥♥ |

| Tuna, Canned (White Albacore) |

♥♥♥ |

| Swordfish, Wild |

♥♥♥ |

| Trout, Farmed (Rainbow) |

♥♥♥ |

| Oysters, Wild & Farmed |

♥♥♥ |

| Mussels, Wild & Farmed |

♥♥♥ |

SEAFOOD PRODUCT

|

|

OMEGA-3s PER 3 OUNCE COOKED PORTION

|

| Tuna, Canned (Light) |

♥♥ |

200 to 500 milligrams |

| Tuna, Wild (Skipjack) |

♥♥ |

| Pollock, Wild (Alaskan) |

♥♥ |

| Rockfish, Wild (Pacific) |

♥♥ |

| Clams, Wild & Farmed |

♥♥ |

| Crab, Wild (King, Dungeness & Snow) |

♥♥ |

| Lobster, Wild (Spiny) |

♥♥ |

| Snapper, Wild |

♥♥ |

| Grouper, Wild |

♥♥ |

| Flounder/Sole, Wild |

♥♥ |

| Halibut, Wild (Pacific & Atlantic) |

♥♥ |

| Ocean Perch, Wild |

♥♥ |

| Squid, Wild (Fried) |

♥♥ |

| Fish Sticks (Breaded) |

♥♥ |

SEAFOOD PRODUCT

|

|

OMEGA-3s PER 3 OUNCE COOKED PORTION

|

| Scallops, Wild |

♥ |

< 200 milligrams |

| Shrimp, Wild & Farmed |

♥ |

| Lobster, Wild (Northern) |

♥ |

| Crab, Wild (Blue) |

♥ |

| Cod, Wild |

♥ |

| Haddock, Wild |

♥ |

| Tilapia, Farmed |

♥ |

| Catfish, Farmed |

♥ |

| Mahimahi, Wild |

♥ |

| Tuna, Wild (Yellowfin) |

♥ |

| Orange Roughy, Wild |

♥ |

| Surimi Product (Imitation Crab) |

♥ |

Source: USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference

by Erik Lovestrand | Sep 25, 2020

Hard work and perseverance are a must for oyster farmers.

On September 17, 2020, President Trump and US Secretary of Agriculture, Sonny Perdue, announced a second phase of an important program assisting America’s farmers. The Coronavirus Food Assistance Program (CFAP 1) was originally announced in April 2020 and now CFAP 2 will provide up to an additional $40 billion in support, along with adding more than 40 specialty crops not previously covered under CFAP 1.

This will be welcome news for many Panhandle farmers; particularly the ones that conduct their “chores” in our Panhandle bays and bayous by producing aquacultured oysters and clams. Losses in sales of molluscan shellfish were not covered under CFAP 1 because they were eligible for some assistance under the CARES Act (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security). However, many local growers were not able to qualify under the CARES Act for various reasons and are in serious need of assistance. When restaurants and bars were forced to close during the pandemic, sales of fresh oysters and clams basically came to a standstill overnight. Many creative efforts at direct marketing to customers and other avenues to move these time-sensitive products have been undertaken but sales are still far from what they were in 2019, leaving many growers with bills to pay and a significantly reduced bottom line.

Applications for CFAP 2 will be accepted by the USDA from September 21 through December 11, 2020. Payments will be based on 2019 sales, excepting new farmers who had no sales in 2019. Their calculations will be based on 2020 sales up to the point of application. The percent-payment-factor will be figured on a sliding scale, depending on amount of sales; ranging from 10.6% for sales below $50,000 to 8.8% for sales over $1 million.

The USDA has done a very good job of laying out information regarding the program on their website (here) and also provide assistance through their local Farm Service Agency offices around the state. Assistance with applications is available on line at this link. Two of the counties that have a significant and growing oyster aquaculture industry in the mid-Panhandle are Wakulla and Franklin. The FSA office for Wakulla County is in Monticello and can be called at (850) 997-2072 ext 2, or email Melissa Rodgers at melissa.rodgers@usda.gov. Growers in Franklin County can reach their FSA office in Blountstown at (850) 674-8388 ext 2, or email Brent Reitmeier at brent.reitmeier@usda.gov.

Growing oysters in floating bags requires getting wet, alot

With the plethora of confusing acronyms flying around in our present day, CFAP is one worth paying attention to. Why? Because it is providing targeted assistance to a segment of our US economy we should all stand behind. Agriculture is a critical component of all of our lives each and every day. If you have a chance to thank a farmer for what they do, or a legislator for moving this effort forward, or an industry support group that provided the data the legislator needed; don’t miss the opportunity. The hard-working men and woman who produce our food supply, including great, locally grown fresh seafood, deserve it.