by Andrea Albertin | Aug 27, 2021

Prepare an emergency drinking water supply for your household before a storm hits. Image: Tyler Jones, UF/IFAS.

Storm season is upon us. During a natural disaster, normal drinking water supplies can quickly become contaminated. To be prepared, collect and store a safe drinking water supply for your household before a storm arrives.

How much water should be stored?

- Store enough clean water for everyone in the household to use 1 to 1.5 gallons per day for drinking and personal hygiene (small amounts for things like brushing teeth). Increase this amount if there are children, sick people, and/or nursing mothers in the home. If you have pets, store a quart to a gallon per pet per day, depending on its size.

- Store a minimum 3-day supply of drinking water. If you have the space for it, consider storing up to a two-week supply.

- For example, a four-person household requiring 1.5 gallons per person per day for 3 days would need to store 18 gallons: 4 people × 1.5 gallons per person × 3 days = 18 gallons. Don’t forget to include additional water for pets!

What containers can be used to store drinking water?

Store drinking water in thoroughly washed food-grade safe containers, which include food-grade plastic, glass containers, and enamel-lined metal containers, all with tight-fitting lids. These materials will not transfer harmful chemicals into the water or food they contain.

More specific examples include containers previously used to store beverages, like 2-liter soft drink bottles, juice bottles or containers made specifically to hold drinking water. Avoid plastic milk jugs if possible because they are difficult to clean. If you are going to purchase a container to store water, make sure it is labeled food-grade or food-safe.

As an extra safety measure, sanitize containers with a solution of 1 teaspoon of non-scented household bleach per quart of water (4 teaspoons per gallon of water). Use bleach that contains 5%–9% sodium hypochlorite. Add the solution to the container, close tightly and shake well, making sure that the bleach solution touches all the internal surfaces. Let the container sit for 30 seconds and pour the solution out. You can let the container air dry before use or rinse it thoroughly with clean water.

Best practices when storing drinking water

- Store water away from direct sunlight, in a cool dark place if possible. Heat and light can slowly damage plastic containers and can eventually lead to leaks.

- Make sure caps or lids are tightly secured.

- Store smaller containers in a freezer. You can use them to help keep food cool in the refrigerator if the power goes out during a storm.

- Keep water containers away from toxic substances (such as gasoline, kerosene, or pesticides). Vapors from these substances can penetrate plastic.

- When possible, use water from opened containers in one or two days if they can’t be refrigerated.

- Although properly stored public-supply water should have an indefinite shelf life, replace every 6-12 months for best taste.

More information on preparing an emergency drinking water supply can be found on the CDC website and in the EDIS Publication ‘Preparing and Storing an Emergency Safe Drinking Water Supply‘

by Andrea Albertin | Apr 9, 2021

Many of Florida’s historic first magnitude springs are classified as nitrogen impaired. Image credit: UF/IFAS Communications

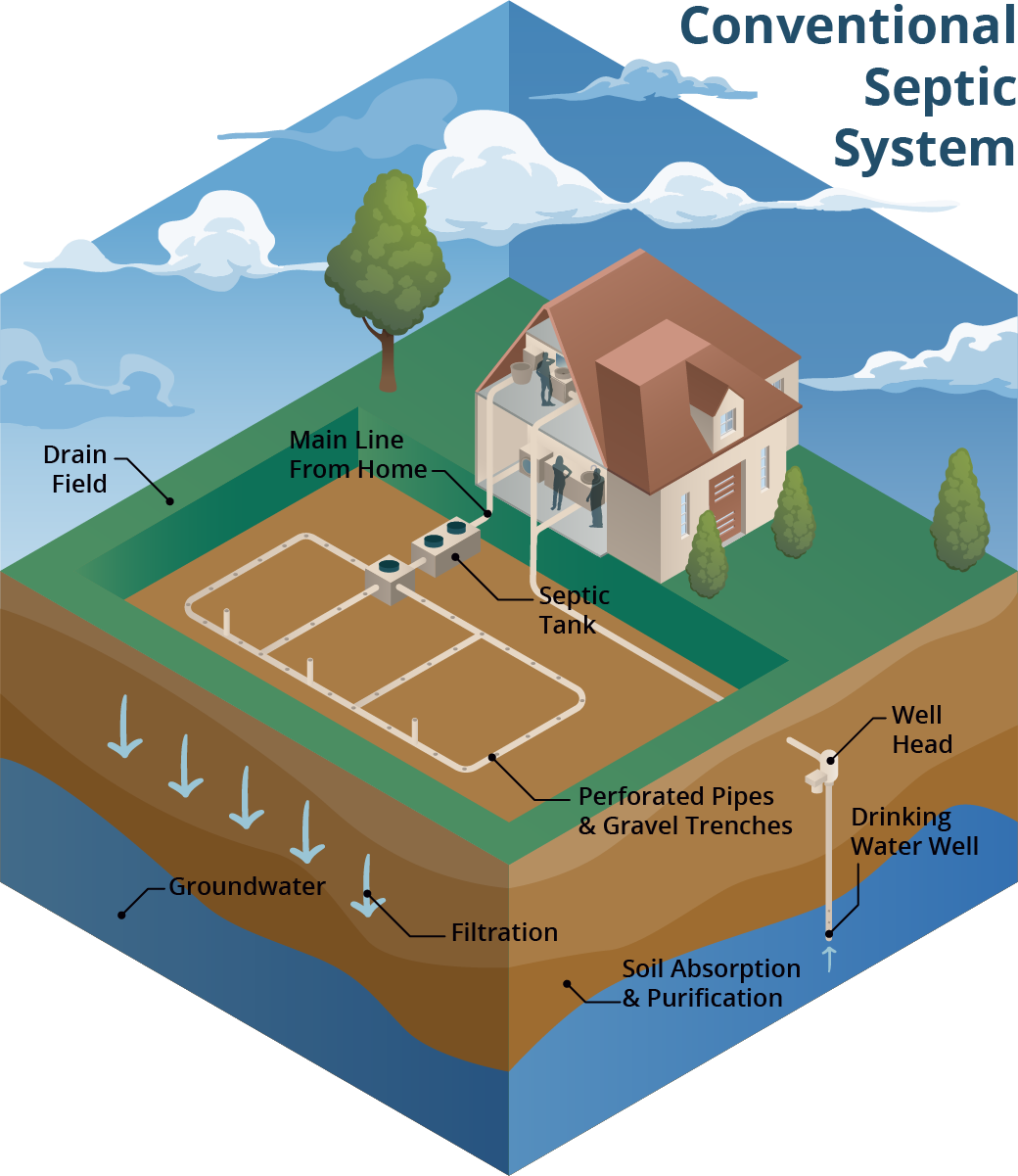

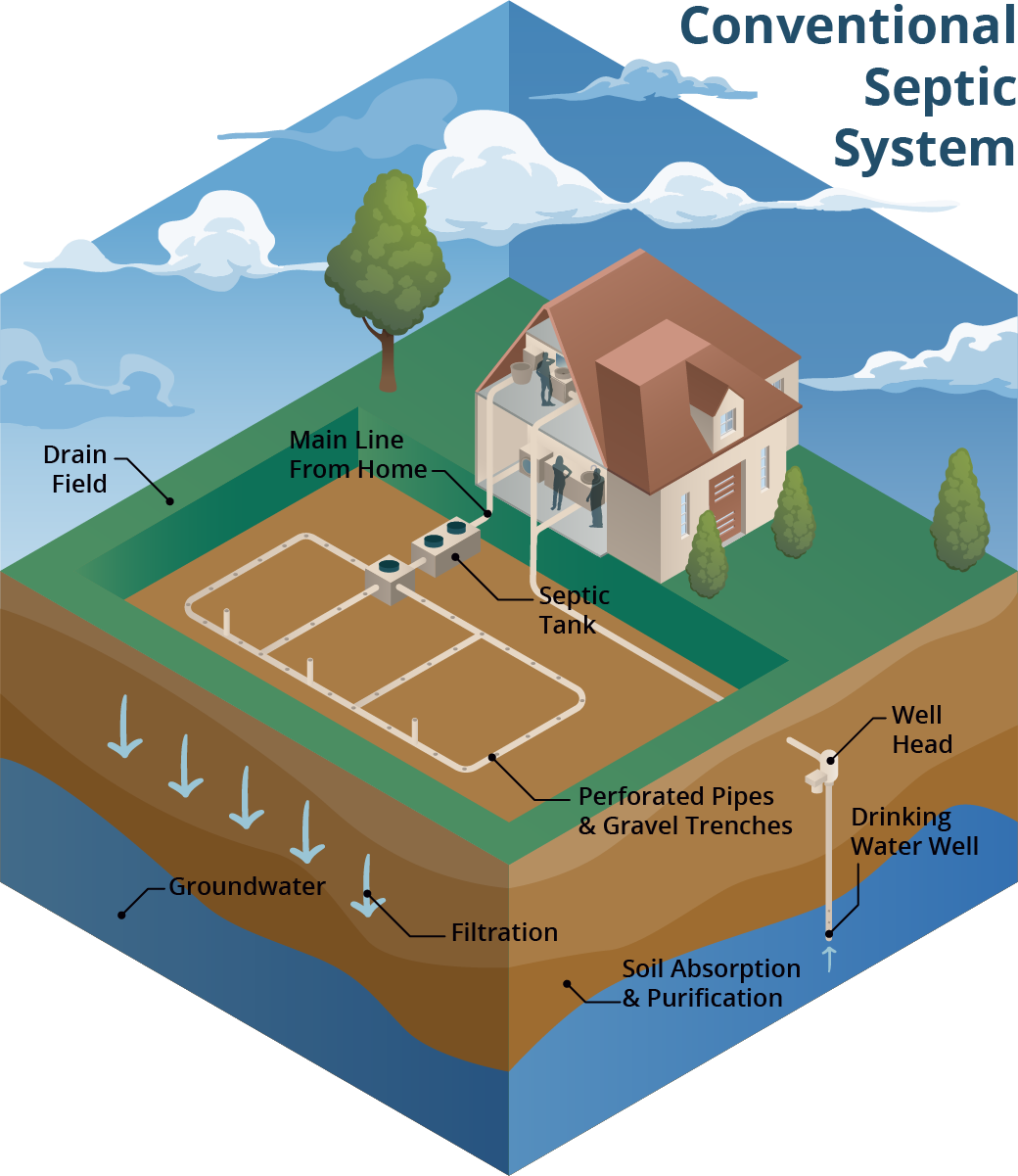

Septic systems are an effective means of treating wastewater when they are properly designed, constructed and maintained. Conventional systems are designed from a public health perspective and have been widely used since the 1940s to remove pathogens and protect human health. About 30% of Florida’s population relies on septic systems, which treat and dispose household wastewater drained from bathrooms, kitchens and laundry machines.

However, septic systems were not designed to remove nutrients. A conventional system removes only about 30 percent of the nitrogen that flows into it. Even a well-maintained system will become a source of nitrogen (particularly nitrate-nitrogen) to the surrounding soil in the drainfield, and may leach to groundwater. Excess nitrogen in Florida’s waterbodies can be a contributing factor to ecological community degradation and increases in algae.

What alternatives are there to conventional septic systems?

Many enhanced nitrogen removal technologies exist, but only those approved by the Florida Department of Health (FDOH) can be installed. Conventional septic systems are made up of a septic tank and a drainfield (or leachfield). Advanced treatment systems add steps to conventional system processes to improve contaminant removal. Types of advanced nitrogen removal technologies available include:

- Aerobic Treatment Units ATUs are made of fiberglass, polyurethane or concrete. Unlike conventional systems, ATUs introduce air into the sewage in the tank using a pump. By aerating waste, the organic matter in the tank is broken down faster than in a conventional system. Effluent from an ATU is discharged into a drainfield for further treatment in the soil, just as with a conventional septic system. ATUs require higher energy input than conventional septic systems to power the aerator, and regular operation and maintenance to sustain performance ATU example from the US EPA

- Performance Based Treatment Systems PBTS are specialized systems designed by professional engineers to meet specific levels of contaminant removal based on site and/or situation requirements. There are many proprietary commercial options available. Designs often include an ATU. Like ATUs, PBTS require higher energy input than conventional septic systems to power pumps, and regular maintenance is needed to sustain performance.

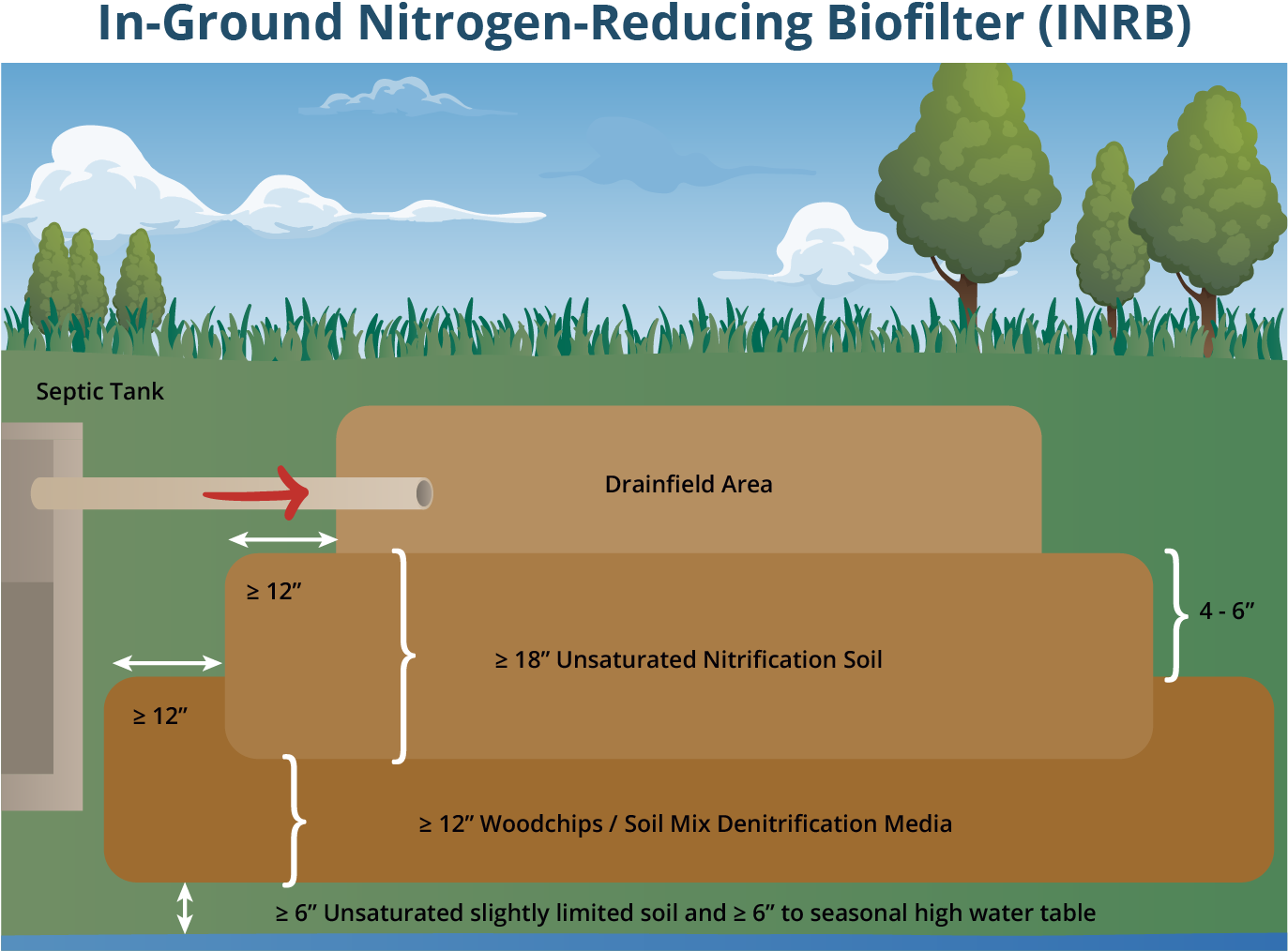

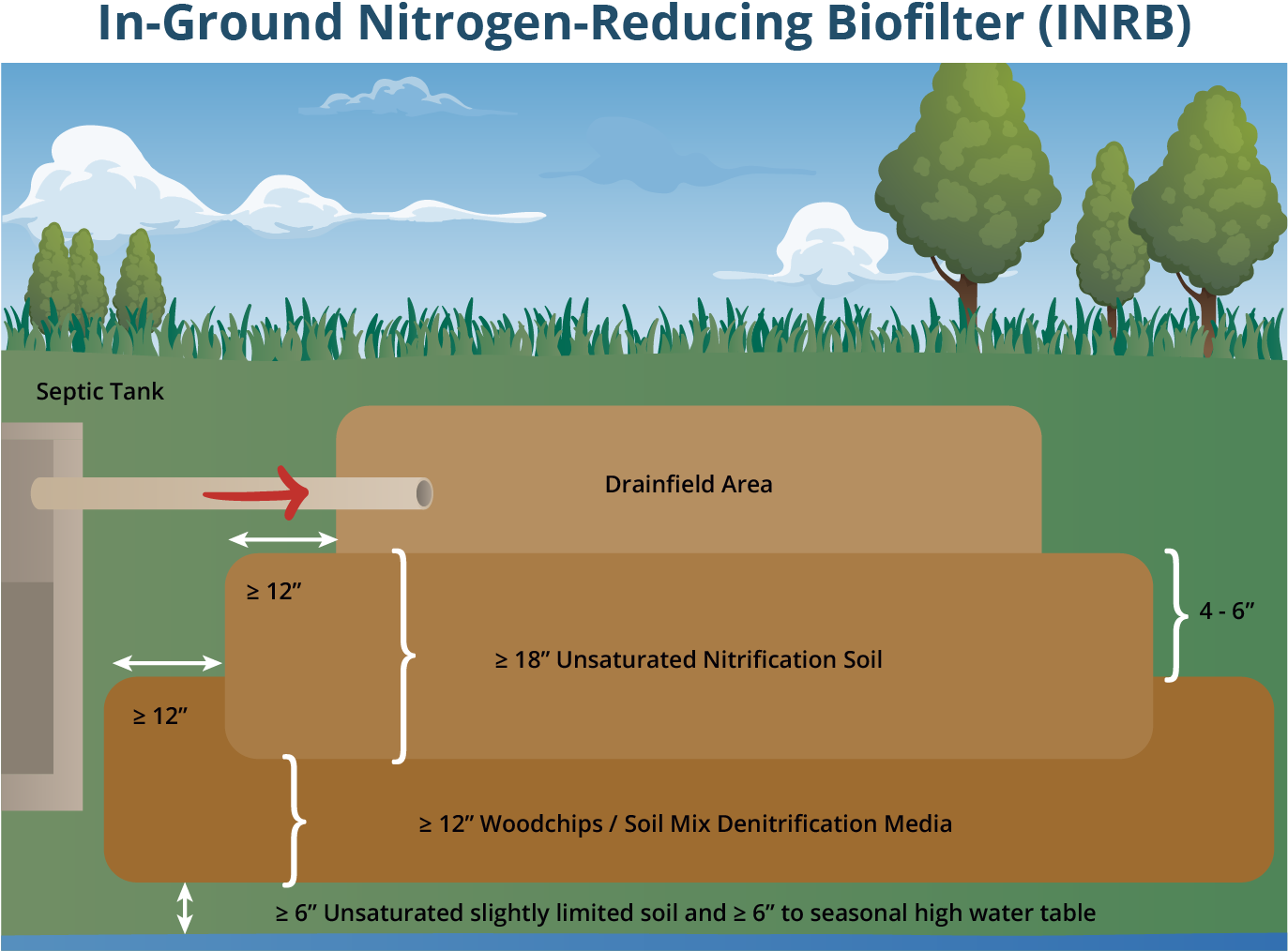

- In-Ground Nitrogen Removing Biofilters INRB are also referred to as modified drainfields. These systems are passive, which means they require no electric aerators or pumps to treat wastewater, and maintenance requirements are lower than those for ATUs and PBTS. INRBs are nitrogen-reducing media layers placed underneath a conventional drainfield.

Ammonium-nitrogen in wastewater leaving the septic tank moves down through the Drainfield Area soil and an additional oxygen-rich zone (Unsaturated Nitrification Soil) to promote conversion into nitrate-nitrogen. Wastewater then passes through a low-oxygen, carbon-rich zone to promote denitrification (Woodchips/Soil Mix Denitrification Media). Denitrification is a process by which specialized bacteria convert nitrate into nitrogen gas that escapes into the atmosphere. This reduces the amount of nitrogen that can leach into groundwater.

FDOH provides comprehensive information about advanced treatment systems and requirements on their product listing and approval requirement web page.

Where are advanced treatment systems required?

The short answer is wherever a septic system remediation plan to protect Florida Springs has been put into place. The 2016 Florida Springs and Aquifer Protection Act was passed to protect 30 ‘Outstanding Florida Springs.’ The majority are historic first magnitude springs, springs with flows of more than 100 cubic ft/second. Twenty-four of these springs are identified as nitrogen impaired by the Florida Department of Environmental Protection.

If septic systems contribute more than 20% of the nitrogen load to the impaired spring, a remediation plan takes effect in specific areas (Priority Focus Areas) that are particularly susceptible to nitrogen pollution. Septic system remediation plans require new development to connect to central sewer where available. If this isn’t an option, new construction on lots of less than 1 acre must include advanced nitrogen-removal technology. In the Panhandle, areas around Wakulla Springs and Jackson Blue Springs have remediation plans.

The best source of information about specific remediation plans and whether or not you live in a Priority Focus Area is FDOH. Contact your local County Department of Health Office to find out if you live in a PFA or if you have questions about septic tank requirements, permitting and approved advanced nitrogen-treatment features for septic systems.

For more information and resources about conventional septic systems and advanced treatment system visit our UF/IFAS Septic Systems website.

by Andrea Albertin | Jan 28, 2021

Senate Bill 712 ‘The Clean Waterways Act’ was signed into Florida law on June 30, 2020. The purpose of the bill is to better protect Florida’s water resources and focuses on minimizing the impact of known sources of nutrient pollution. These sources include septic systems, wastewater treatment plants, stormwater runoff as well as fertilizer used in agricultural production.

Senate Bill 712 focuses on protecting Florida’s water resources such as Jackson Blue Springs/Merritt’s Mill Pond, pictured here. Credit: Doug Mayo, UF/IFAS.

What major provisions are included in SB 712?

Primary actions required by SB712 were listed in a news release by Governor Desantis’ staff in June 2020 as:

- Regulation of septic systems as a source of nutrients and transfer of oversight from the Florida Department of Health (DOH) to the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (DEP).

- Contingency plans for power outages to minimize discharges of untreated wastewater for all sewage disposal facilities.

- Provision of financial records from all sanitary sewage disposal facilities so that DEP can ensure funds are being allocated to infrastructure upgrades, repairs, and maintenance that prevent systems from falling into states of disrepair.

- Detailed documentation of fertilizer use by agricultural operations to ensure compliance with Best Management Practices (BMPs) and aid in evaluation of their effectiveness.

- Updated stormwater rules and design criteria to improve the performance of stormwater systems statewide to specifically address nutrients.

How does the bill impact septic system regulation?

The transfer of the Onsite Sewage Program (OSP) (commonly known as the septic system program) from DOH to DEP becomes effective on July 1, 2021. So far, DOH and DEP submitted a report to the Governor and Legislature at the end of 2020 with recommendations on how this transfer should take place. They recommend that county DOH employees working in the OSP continue implementing the program as DOH-employees, but that the onsite sewage program office in the State Health Office transfer to DEP and continue working from there. DOH created an OSP Transfer web page where updates and documents related to the transfer are posted.

How does the bill impact agricultural operations?

SB 712 affects all landowners and producers enrolled in the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (FDACS) BMP Program. Under this bill:

- Every two years FDACS will make an onsite implementation verification (IV) visit to land enrolled in the BMP program to ensure that BMPs are properly implemented. These visits will be coordinated between the producer and field staff from FDACS Office of Agriculture and Water Policy (OAWP).

- During these visits (and as they have done in the past), field staff will review records that producers are required to keep under the BMP program.

- Field staff will also collect information on nitrogen and phosphorus application. FDACS has created a specific form, the Nutrient Application Record Keeping Form or NARF where producers will record quantities of N and P applied. FDACS field staff will retain a copy of the NARF during the IV visit.

FDACS-OAWP prepared a thorough document with responses to SB 712 Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ’s). It includes responses to questions about site visits, the NARF and record keeping, why FDACS is collecting nutrient records and what will be done with this information. The fertilizer records collected are not public information, and are protected under the public records exemption (Section 403.067 Florida Statutes). For areas that fall under a Basin Management Action Plan (like the Jackson Blue and Wakulla Springs Basins in the Florida Panhandle), FDACS will combine the nitrogen and phosphorus application data from all enrolled properties (total pounds of N and P applied within the BMAP). It will then send the aggregated nutrient application information to FDEP.

Details of how all aspects of SB 712 will be implemented are still being worked out and we should continue to hear more in the coming months.

by Carrie Stevenson | Jan 8, 2021

Well-maintained stormwater ponds can become attractive amenities that also improve water quality. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Prior to joining UF IFAS Extension, I spent three years as a compliance and enforcement field inspector with the local Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) office. It was a crash course in drinking water regulation, wetlands ecology, stormwater engineering, and human psychology. For about half of that time, I worked in the stormwater section with an engineer, certifying the proper construction and specifications of stormwater treatment ponds built for residential and commercial developments. During a construction boom in 2000-2003, my coworkers and I traversed back roads from Perdido Key to Freeport, trying to catch every new project and make sure it was done right. If they weren’t, it also fell to the 3 of us to make sure mistakes were corrected.

Since 1982, Florida Statutes have required that rainfall landing on newly constructed impervious surfaces (rooftops, streets, parking lots, etc.) must be treated before turning into runoff that leaves the property and ends up in local water bodies. The pollutants in stormwater runoff—heavy metals, fertilizer, pesticides, trash, bacteria, and sediment—are the biggest sources of water quality problems for the state, more so even than industrial and agricultural sources.

The most common stormwater ponds have sandy bottoms, grassed berms, and piped inlets with riprap to slow the influx of water. Photo credit, Michelle Diller

Therefore, new developments are required to treat that runoff. This may be accomplished by several means, including regional stormwater ponds. However, the most common are still curbs and gutters, which drain to an often-rectangular hole in the ground with a chain-link fence around it. Ideally, water pools into these dry ponds while raining, reducing flood risk and holding water long enough to allow it to soak into the soil. Most of the ponds in northwest Florida have sandy bottoms that percolate easily. Maintenance is required, however, and when heavier soils, trash, or muck accumulate they must be cleaned out to function properly. Depending on the geology of any given location, the ponds may need sand filters or “chimneys” added to allow water to soak into the native soil.

Admiral Mason Park, adjacent to the Veterans’ Memorial Park along Pensacola Bay, is an example of a regional City stormwater treatment facility that also serves as a park. Photo credit: Visit Pensacola

If an area is naturally low-lying, close to the water table, or has highly organic, water-holding soils, it may be necessary to construct a “wet” stormwater pond. In these, water stands to a level below an overflow device, and can become a water feature for the development. Many residential developers will sell lots around a stormwater pond as “waterfront property” and a well-maintained one really can be a nice amenity. However, at their core, these are stormwater treatment mechanisms. A wet pond functions differently than a dry one and is dependent on healthy stands of shoreline vegetation to take up extra nutrients, metabolize them, and render them into harmless compounds. Many of these ponds have fountains to aerate the water and keep them from becoming stagnant. The City of Pensacola and Escambia County have several great examples of these types of ponds that serve as regional stormwater detention and community amenities. These were constructed in lower-lying areas to handle chronic problems with stormwater in areas that were built up and paved many decades before stormwater rules came into effect. Many other innovative and newer stormwater treatments exist as well, including bioretention, rainwater harvesting, green roofs, and pervious pavement.

by Andrea Albertin | Oct 9, 2020

Special care needs to be taken with your septic system after flooding. Image: B. White NASA. Public Domain

During and after floods or heavy rains, the soil in your septic system drainfield can become waterlogged. For your septic system to treat wastewater, water needs to drain freely in the drainfield. Special care needs to be taken with your septic system under flood conditions.

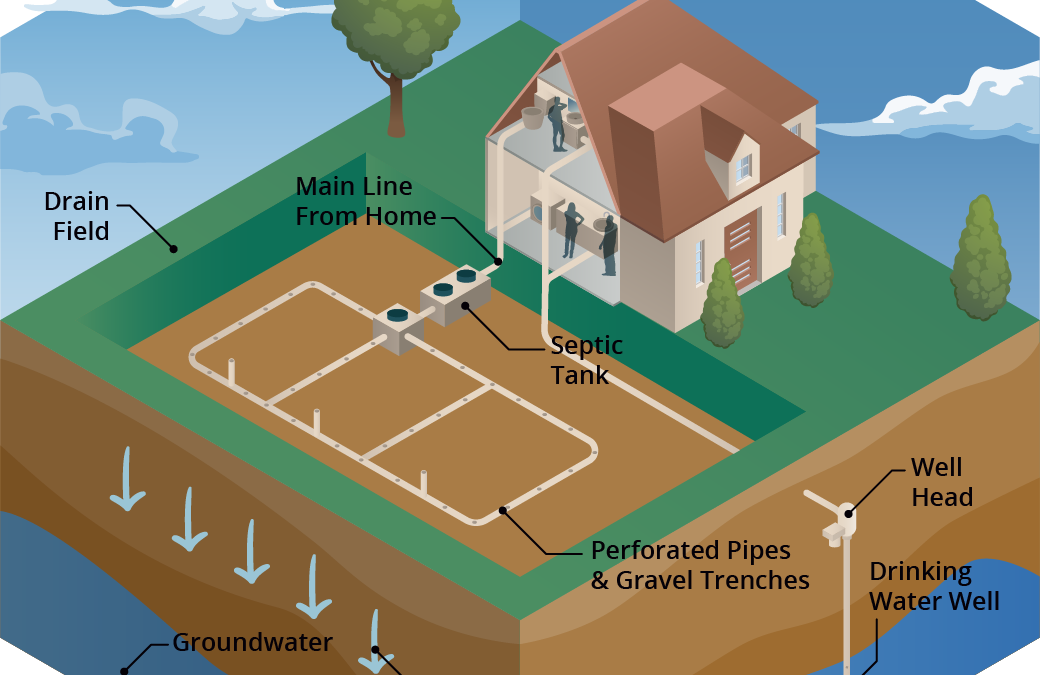

A conventional septic system is made up of a septic tank (a watertight container buried in the gound) and a drainfield. Image: Soil and Water Science Lab UF/IFAS GREC.

A conventional septic system is made up of a septic tank and a drainfield or leach field. Wastewater flows from the septic tank into the drainfield, which is typically made up of a distribution box (to ensure the wastewater is distributed evenly) and a series of trenches or a single bed with perforated PVC pipes. Wastewater seeps from these pipes into the surrounding soil. Most wastewater treatment occurs in the drainfield soil. When working properly, many contaminants, like harmful bacteria, are removed through die-off, filtering and interaction with soil surfaces.

What should you do if flooding occurs?

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) offers these guidelines:

- Relieve pressure on the septic system by using it less or not at all until floodwaters recede and the soil has drained. Under flooded conditions, wastewater can’t drain in the drainfield and can back up in your septic system and household drains. Clean up floodwater in the house without dumping it into the sinks or toilet. This adds additional water that an already saturated drainfield won’t be able to process. Remember that in most homes all water sent down the pipes goes into the septic system.

- Avoid digging around the septic tank and drainfield while the soil is waterlogged. Don’t drive vehicles or equipment over the drainfield. Saturated soil is very susceptible to compaction. By working on your septic system while the soil is still wet, you can compact the soil in your drainfield, and water won’t be able to drain properly. This reduces the drainfield’s ability to treat wastewater and leads to system failure.

- Don’t open or pump the septic tank if the soil is waterlogged. Silt and mud can get into the tank if it is opened and can end up in the drainfield, reducing its drainage capability. Pumping under these conditions can cause a tank to float or ‘pop out’ of the ground, and can damage inlet and outlet pipes.

- If you suspect your system has been damaged, have the tank inspected and serviced by a professional. How can you tell if your system is damaged? Signs include: settling, wastewater backs up into household drains, the soil in the drainfield remains soggy and never fully drains, a foul odor persists around the tank and drainfield.

- Keep rainwater drainage systems away from the septic drainfield. As a preventive measure, make sure that water from roof gutters doesn’t drain towards or into your septic drainfield. This adds an additional source of water that the drainfield has to process.

- Have your private well water tested if your septic system or well were flooded or damaged in any way. Your well water may not be safe to drink or use for household purposes (making ice, cooking, brushing teeth or bathing). You need to have it tested by the Health Department or other certified laboratory for total coliform bacteria and coli to ensure it is safe to use.

For more information on septic system maintenance after flooding, go to:

More information on having your well water tested can be found at:

More Information on conventional and advanced treatment septic systems can be found on the UF/IFAS Septic System website

by Andrea Albertin | Oct 2, 2020

If your private well was damaged or flooded due to hurricane or other heavy storm activity, your well water may not be safe to drink. Well water should not be used for drinking, cooking purposes, making ice, brushing teeth or bathing until it is tested by a certified laboratory for total coliform bacteria and E. coli.

Residents should use bottled, boiled or treated water until their well water has been tested and deemed safe.

- Boiling: To make water safe for drinking, cooking or washing, bring it to a rolling boil for at least one minute to kill organisms and then allow it to cool.

- Disinfecting with bleach: If boiling isn’t possible, add 1/8 of a teaspoon or about 8 drops of fresh unscented household bleach (4 to 6% active ingredient) per gallon of water. Stir well and let stand for 30 minutes. If the water is cloudy after 30 minutes, repeat the procedure once.

- Keep treated or boiled water in a closed container to prevent contamination

Use bottled water for mixing infant formula.

Where can you have your well water tested?

Contact your county health department for information on how to have your well water tested. Image: F. Alvarado Arce

Most county health departments accept water samples for testing. Contact your local department for information about what to have your water tested for (they may recommend more than just bacteria), and how to collect and submit the sample.

Contact information for Florida Health Departments can be found here: County Health Departments – Location Finder

You can also submit samples to a certified commercial lab near you. Contact information for commercial laboratories that are certified by the Florida Department of Health are found here: Laboratories certified by FDOH

This site includes county health department labs, commercial labs as well as university labs. You can search by county.

What should you do if your well water sample tests positive for bacteria?

The Florida Department of Health recommends well disinfection if water samples test positive for total coliform bacteria or for both total coliform and E. coli, a type of fecal coliform bacteria.

You can hire a local licensed well operator to disinfect your well, or if you feel comfortable, you can shock chlorinate the well yourself.

You can find information on how to shock chlorinate your well at:

After well disinfection, you need to have your well water re-tested to make sure it is safe to use. If it tests positive again for total coliform bacteria or both total coliform and E. coli call a licensed well operator to have the well inspected to get to the root of the problem.

Well pump and electrical system care

If the pump and/or electrical system have been underwater and are not designed to be used underwater, do not turn on the pump. There is a potential for electrical shock or damage to the well or pump. Stay away from the well pump while flooded to avoid electric shock.

Once the floodwaters have receded and the pump and electrical system have dried, a qualified electrician, well operator/driller or pump installer should check the wiring system and other well components.

Remember: You should have your well water tested at any time when:

- A flood occurred and your well was affected

- The color, taste or odor of your well water changes or if you suspect that someone became sick after drinking your well water.

- A new well is drilled or if you have had maintenance done on your existing well

- There has been any type of chemical spill (pesticides, fuel, etc.) into or near your well

The Florida Department of Health maintains an excellent website with many resources for private well users: FDOH Private Well Testing and other Reosurces which includes information on potential contaminants and how to maintain your well to ensure the quality of your well water.