by Mark Mauldin | Apr 9, 2021

Spring can be a busy time of year for those of us who are interested in improving wildlife habitat on the property we own/manage. Spring is when we start many efforts that will pay-off in the fall. If you are a weekend warrior land manager like me there is always more to do than there are available Saturdays to get it done. The following comments are simple reminders about some habitat management activities that should be moving to the top of your to-do list this time of year.

Aquatic Weed Management – If you had problematic weeds in you pond last summer, chances are you will have them again this summer. NOW (spring) is the time to start controlling aquatic weeds. The later into the summer you wait the worse the weeds will get and the more difficult they will be to control. The risk of a fish-kill associated with aquatic weed control also increases as water temperatures and the total biomass of the weeds go up. Springtime is “Just Right” for Using Aquatic Herbicides

Cogongrass Control – Spring is actually the second-best time of year to treat cogongrass, fall (late September until first frost) is the BEST time. That said, ideally cogongrass will be treated with herbicide every six months, making spring and fall important. When treating spring regrowth make sure that there are green leaves at least one foot long before spraying. Spring is also an excellent time of year to identify cogongrass patches – the cottony, white blooms are easy to spot. Identify Cogongrass Now – Look for the Seedheads; Cogongrass – Now is the Best Time to Start Control

Cogongrass seedheads are easily spotted this time of year.

Photo credit: Mark Mauldin

Warm-Season Food Pots – There is a great deal of variation in when warm season food plots can be planted. Assuming warm-season plots will be panted in the same areas as cool-season plots, the simplest timing strategy is to simply wait for the cool-season plots to play out (a warm, dry May is normally the end of even the best cool-season plot) and then begin preparation for the warm-season plots. This transition period is the best time to deal with soil pH issues (get a soil test) and control weeds. Seed for many varieties of warm-season legumes (which should be the bulk of your plantings) can be somewhat hard to find, so start looking now. If you start early you can find what you want, and not just take whatever the feed store has. Warm Season Food Plots for White-tailed Deer

Deer Feeders – Per FWC regulations deer feeders need to be in continual operation for at least six months prior to hunting over them. Archery season in the Panhandle will start in mid-October, meaning deer feeders need to be up and running by mid-April to be legal to hunt opening morning. If you have plans to move or add feeders to your property, you’d better get to it pretty soon. FWC Feeding Game

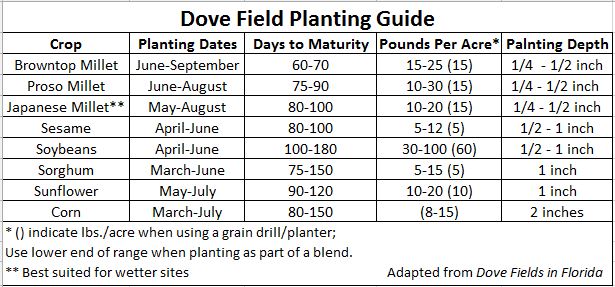

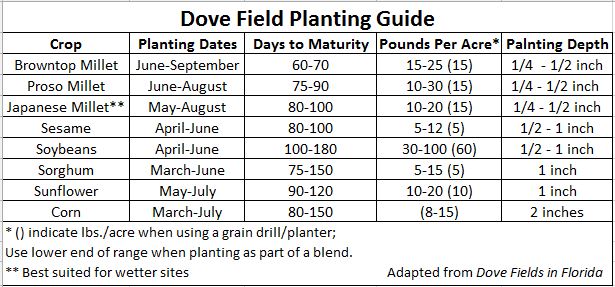

Dove Fields – The first phase of dove season will begin in late September. When you look at the “days to maturity” for the various crops in the chart below you might feel like you’ve got plenty of time. While that may be true, don’t forget that not only do you need time for the crop to mature, but also for seeds to begin to drop and birds to find them all before the first phase begins. Because doves are particularly fond of feeding on clean ground, controlling weeds is a worthwhile endeavor. If you are planting on “new ground”, applying a non-selective herbicide several weeks before you begin tillage is an important first step to a clean field, but it adds more time to the process. As mentioned above, it’s always pertinent to start sourcing seed well in advance of your desired planting date. Timing is Crucial for Successful Dove Fields

There are many other projects that may be more time sensitive than the ones listed above. These were just a few that have snuck up on me over the years. The links in each section will provide more detailed information on the topics. If you have questions about anything addressed in the article feel free to contact me or your county’s UF/IFAS Extension Natural Resource Agent.

by Sheila Dunning | Jan 28, 2021

Groundhog

Groundhog Day is celebrated every year on February 2, and in 2021, it falls on Tuesday. It’s a day when townsfolk in Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania, gather in Gobbler’s Knob to watch as an unsuspecting furry marmot is plucked from his burrow to predict the weather for the rest of the winter. If Phil does see his shadow (meaning the Sun is shining), winter will not end early, and we’ll have another 6 weeks left of it. If Phil doesn’t see his shadow (cloudy) we’ll have an early spring. Since Punxsutawney Phil first began prognosticating the weather back in 1887, he has predicted an early end to winter

only 18 times. However, his accuracy rate is only 39%. In the south, we call also defer to General Beauregard Lee in Atlanta, Georgia or Pardon Me Pete in Tampa, Florida.

But, what is a groundhog? Are gophers and groundhogs the same animal? Despite their similar appearances and burrowing habits, groundhogs and gophers don’t have a whole lot in common—they don’t even belong to the same family. For example, gophers belong to the family Geomyidae, a group that includes pocket gophers, kangaroo rats, and pocket mice. Groundhogs, meanwhile, are members of the Sciuridae (meaning shadow-tail) family and belong to the genus Marmota. Marmots are diurnal ground squirrels. There are 15 species of marmot, and groundhogs are one of them.

Science aside, there are plenty of other visible differences between the two animals. Gophers, for example, have hairless tails, protruding yellow or brownish teeth, and fur-lined cheek pockets for storing food—all traits that make them different from groundhogs. The feet of gophers are often pink, while groundhogs have brown or black feet. And while the tiny gopher tends to weigh around two or so pounds, groundhogs can grow to around 13 pounds.

While both types of rodent eat mostly vegetation, gophers prefer roots and tubers while groundhogs like vegetation and fruits. This means that the former animals rarely emerge from their burrows, while the latter are more commonly seen out and about. In the spring, gophers make what is called eskers, or winding mounds of soil. The southeastern pocket gopher, Geomys pinetis, is also known as the sandy-mounder in Florida.

Southeastern Pocket Gopher

The southeastern pocket gopher is tan to gray-brown in color. The feet and naked tail are light colored. The southeastern pocket gopher requires deep, well-drained sandy soils. It is most abundant in longleaf pine/turkey oak sandhill habitats, but it is also found in coastal strand, sand pine scrub, and upland hammock habitats.

Gophers dig extensive tunnel systems and are rarely seen on the surface. The average tunnel length is 145 feet (44 m) and at least one tunnel was followed for 525 feet (159 m). The soil gophers remove while digging their tunnels is pushed to the surface to form the characteristic rows of sand mounds. Mound building seems to be more intense during the cooler months, especially spring and fall, and slower in the summer. In the spring, pocket gophers push up 1-3 mounds per day. Based on mound construction, gophers seem to be more active at night and around dusk and dawn, but they may be active at any time of day.

Pocket Gopher Mounds

Many amphibians and reptiles use pocket gopher mounds as homes, including Florida’s unique mole skinks. The pocket gopher tunnels themselves serve as habitat for many unique invertebrates found nowhere else.

So, groundhogs for guesses on the arrival of spring. But, when the pocket gophers are making lots of mounds, spring is truly here. Happy Groundhog’s Day.

by Mark Mauldin | Oct 23, 2020

Archery season for white tailed deer opens this Saturday (10/24/20) in FWC Hunting Zone D (basically the Panhandle west of Tallahassee, see figure 1). Before you go hunting be sure that you have a plan in place for logging and reporting your harvest. Last year FWC implemented a mandatory harvest reporting system. That system is still in effect this year but with some modifications.

Figure 1. FWC Hunting Zone D

myfwc.com

The most notable change to the harvest reporting system this year is with the associated smart phone app. There is a new app this year – Fish|Hunt Florida. This new app will replace the Survey123 for ArcGIS app that was used last year.

In my opinion, the logging and reporting function on the Fish|Hunt Florida app is simpler to use than the previous app. Additionally the Fish|Hunt Florida app has many other useful features. A few highlights include; the ability to view and purchase hunting and fishing licenses/permits through the app, interactive versions of hunting and fishing regulations, and several other handy resources for sportsmen including, marine forecasts, tides, wildlife feeding times, sunrise & sunset times, boat ramp locator and a current location feature. Screenshots from the app are included below. The Fish|Hunt Florida app is available for free through the Apple App Store and the Google Play Store.

Remember, the current regulations state that your deer harvest must be logged before the animal is moved. Take a minute or two to install the app on your phone before you go hunting. Using the app allows logging and reporting to happen simultaneously. The app can be used for logging and reporting a harvest even in areas where cell service is poor. Harvest information will can be saved and the app will automatically complete the process as soon as adequate cell service is available. The alternative to using the app is a two-step process, the harvest can be logged (prior to being moved) on a paper form and then reported by calling 888-HUNT-FLORIDA (888-486-8356) or going to GoOutdoorsFlorida.com within 24 hours.

Follow the link for specific instructions for logging and reporting a harvested deer using the Fish|Hunt Florida app; don’t worry, it’s easy. Fish|Hunt Florida app instructions

For more information on the Fish|Hunt Florida app and the FWC Deer Harvest Reporting System visit myfwc.com.

Screenshot of the Boat Info tab from the Hunt|Fish Florida App. Click on the image to make it larger.

Screenshot of the Fishing Tab from the Hunt|Fish Florida App. Click on the image to make it larger.

Screenshot of the Home screen from the Hunt|Fish Florida App. Click on the image to make it larger.

Screenshot of the Hunting tab from the Hunt|Fish Florida App. Click on the image to make it larger.

by Rick O'Connor | Oct 21, 2020

It’s Halloween…

The time of year we think of werewolves, warlocks, witches, and full moon evenings. But there is another creature who likes to howl at the moon this time of year – the coyote.

A coyote moving on Pensacola Beach near dawn.

Photo provided by Shelley Johnson.

Actually, coyotes howl all throughout the year, and they are not specifically howling at the moon. The name “coyote” is a Native American term meaning “singing dog”, or “barking dog”. They are famous for their early evening and early morning calls. Howls, barks, yelps, and yaps are very familiar to those living out west – and now for those living in the eastern United States.

It is believed the animal originated in the grasslands and deserts of the American southwest feeding on a variety of rodents. They have successfully dispersed across the country and can now be found in almost any habitat in the continental United States – including barrier islands. Though they owe much of their success to their ability to adapt to different foods and habitats, they also owe some of their success to humans. We have reduced their primary predators – bears, wolves, and mountain lions – to a level where they could move around more safely. There have been efforts to restore these predator populations in some localized areas of the U.S., but those are localized, and the process has been slow. All the while the coyote has enjoyed a more predator free world.

They are also opportunistic feeders. Though the bulk of their diet are small rodents, they are known to eat small birds, reptiles, amphibians, rabbits, squirrels, and even fruit. Out west, working in teams, they can take down larger prey – such as deer, and can do so here in the east as well. But their large prey targets are usually smaller members of the herd, sick, or old ones. They have also learned to feed on road kills of these animals.

Then there are humans. We provide an abundance of garbage which they have learned to scavenge through. Pet food left outside, gardens with produce, small livestock, and even pet cats and small dogs have been added to their menu. We have made their world much better.

With their numbers increasing in human populated areas, like Santa Rosa Island, people are becoming a bit nervous around them. The image of the toothed predator howling at the harvest moon on Halloween night in a pack with others makes us a bit uneasy. So, how dangerous are they?

Not very.

Coyotes are intelligent animals, and though they have learned to live and hunt within our neighborhoods, they are still afraid of us – they consider us trouble. On a recent trip to Colorado I was hiking down a trail and saw what appeared to be two sets of pointed ears in the grass. My guess was coyote but was not sure – so I began to walk towards them. Three coyotes immediately got up and moved off across the next ridge. They wanted nothing to do with me. And that is how it should be.

Those on barrier islands, like Santa Rosa, are no different. They are more active at dawn and dusk (crepuscular) and spend their days and late nights in a den somewhere. Occasionally people will see them in the middle of the day, or hear a yelp or howl around 2:00 AM, but it is more of a sunrise and sunset deal for them. They can remain motionless and undetected when people are around and will often run if we get too close. Many are not sure whether they are seeing a coyote or a German shepherd when they see one, both being about the same size. Coyotes tend to run with their tails down, unlike dogs and wolves who prefer to run with their tails up.

All of this said, there have been attacks on people – mostly out west and in southern California in particular. In most cases, the animals have either intentionally or unintentionally been fed by people. When this happens, they lose their fear of us and return for another easy meal. They are wild animals and being cornered by people or dogs (intentionally or unintentionally) can lead to defensive behaviors that could include attacks. To avoid this, we should not approach any coyote. Keep your trash secured and in cans that would be difficult for coyotes to access. Bring your pet food in at night and do not let pet cats and small dogs out in the evenings without supervision.

Bad encounters with these howling animals are rare, and with a little education and behavior changes on our part, should remain so.

Happy Halloween.

by Daniel J. Leonard | Sep 3, 2020

Overcup on the edge of a wet weather pond in Calhoun County. Photo courtesy of Daniel Leonard.

Haunting alluvial river bottoms and creek beds across the Deep South, is a highly unusual oak species, Overcup Oak (Quercus lyrata). Unlike nearly any other oak, and most sane people, Overcups occur deep in alluvial swamps and spend most of their lives with their feet wet. Though the species hides out along water’s edge in secluded swamps, it has nevertheless been discovered by the horticultural industry and is becoming one of the favorite species of landscape designers and nurserymen around the South. The reasons for Overcup’s rise are numerous, let’s dive into them.

The same Overcup Oak thriving under inundation conditions 2 weeks after a heavy rain. Photo courtesy Daniel Leonard.

First, much of the deep South, especially in the Coastal Plain, is dominated by poorly drained flatwoods soils cut through by river systems and dotted with cypress and blackgum ponds. These conditions call for landscape plants that can handle hot, humid air, excess rainfall, and even periodic inundation (standing water). It stands to reason our best tree options for these areas, Sycamore, Bald Cypress, Red Maple, and others, occur naturally in swamps that mimic these conditions. Overcup Oak is one of these hardy species. It goes above and beyond being able to handle a squishy lawn, and is often found inundated for weeks at a time by more than 20’ of water during the spring floods our river systems experience. The species has even developed an interested adaptation to allow populations to thrive in flooded seasons. Their acorns, preferred food of many waterfowl, are almost totally covered by a buoyant acorn cap, allowing seeds to float downstream until they hit dry land, thus ensuring the species survives and spreads. While it will not survive perpetual inundation like Cypress and Blackgum, if you have a periodically damp area in your lawn where other species struggle, Overcup will shine.

Overcup Oak leaves in August. Note the characteristic “lyre” shape. Photo courtesy Daniel Leonard.

Overcup Oak is also an exceedingly attractive tree. In youth, the species is extremely uniform, with a straight, stout trunk and rounded “lollipop” canopy. This regular habit is maintained into adulthood, where it becomes a stately tree with a distinctly upturned branching habit, lending itself well to mowers and other traffic underneath without having to worry about hitting low-hanging branches. The large, lustrous green leaves are lyre-shaped if you use your imagination (hence the name, Quercus lyrata) and turn a not-unattractive yellowish brown in fall. Overcups especially shine in the winter when the whitish gray shaggy bark takes center stage. The bark is very reminiscent of White Oak or Shagbark Hickory and is exceedingly pretty relative to other landscape trees that can be successfully grown here.

Finally, Overcup Oak is among the easiest to grow landscape trees. We have already discussed its ability to tolerate wet soils and our blazing heat and humidity, but Overcups can also tolerate periodic drought, partial shade, and nearly any soil pH. They are long-lived trees and have no known serious pest or disease problems. They transplant easily from standard nursery containers or dug from a field (if it’s a larger specimen), making establishment in the landscape an easy task. In the establishment phase, defined as the first year or two after transplanting, young transplanted Overcups require only a weekly rain or irrigation event of around 1” (wetter areas may not require any supplemental irrigation) and bi-annual applications of a general purpose fertilizer, 10-10-10 or similar. After that, they are generally on their own without any help!

Typical shaggy bark on 7 year old Overcup Oak. Photo courtesy Daniel Leonard.

If you’ve been looking for an attractive, low-maintenance tree for a pond bank or just generally wet area in your lawn or property, Overcup Oak might be your answer. For more information on Overcup Oak, other landscape trees and native plants, give your local UF/IFAS County Extension office a call!

by Rick O'Connor | Aug 21, 2020

You are probably not going to see them… but they are there.

Mammals are fur covered warm blooded creatures. Beaches are hot, dry, sandy places. Just as in the deserts, it would make sense for island mammals to be nocturnal. We know of their existence by their tracks and their scat. Rabbit, raccoon, and armadillo tracks are quite common. Deer, coyote, and beach mice less so. All that said, some are seen at dawn and dusk and it is not unheard of to see them in the middle of the day – especially during the cooler months.

One question that may come up is – “how did they get to an isolated island?” Some scientists have a lot of fun trying to solve that mystery. Some island mammals, like otters, are very good swimmers and would have no problem. Many barrier islands begin as sand spits connected to the mainland – the mammals ventured out into new territory – set up camp – and either over time, or over night in a hurricane – the spit breaks off and the mammals are there. And let’s not forget we built bridges – they know how to use them. Coyotes have been seen walking across the Bob Sikes Bridge from Gulf Breeze.

Another question that comes up – “where are they in the middle of the day?” Most dig, or find, burrows and dens. Just a few inches below the surface it is very cool. Some will find thick hammocks in the maritime forest and “hunker down” for the day.

The sneaky raccoon is an intelligent creature and has learned to live with humans.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

Raccoons

The raccoon (Procyon lotor) is one of the more intelligent and fearless of the beach mammals. Their opportunistic behavior frequently brings them into contact with humans. They will scurry across your lawn at night looking for insects, cat food, garbage, whatever they can find to eat – and outdoor lights do not seem to bother them. There are even videos of them reaching into “dog doors” searching. On the island, their tracks are often found in the marsh areas – where they grab shellfish and are one of the few animals that wash their food before eating it. They usually like to settle into hollow trees during the day. But on the island, it is more likely burrows in the sand.

Their tracks might show the presence of a claw (always hard in soft sand – better chance in wet). The front foot is smaller than the back and they walk with an alternating pattern – usually the front and back foot are close to each other – unless they are running. The front foot is about 2.5”x2.5” – a little round, and the index from the pad to the tip is thinner. The hind foot is about 2.5” wide but closer to 4” long.

The scat is cigar shaped and about 3” long.

Read more:

https://myfwc.com/media/1666/livingwithraccoons.pdf.

The bizarre looking armadillo enjoys a walk on the beach.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Armadillo

Here is an interesting creature. It doesn’t even look like a mammal – not sure what it looks like. But mammals they are. If you find one that has been hit by a car you can see, amongst the armored plating, hairs spaced across the body – they are mammals. It is one that is sometimes seen roaming in the middle of the day. They plunge through the leaf litter and bushes of the maritime forest, making a lot of noise, while searching for insects and grubs and crushing them with their peg-like teeth. They are not from around here – rather from central America – and worked their way into the American southwest and southeast. They probably reached the island via the bridges. They are prolific produces – usually having quadruplets of the same sex. You once found them occasionally in the national seashore – but since Hurricane Ivan, you can find them almost anywhere. One bothersome fact of this animal – they are known to carry leprosy – which can be contacted by eating the animal, or handling it.

Their tracks are one of the most common on the beach. The front foot is about 1.8” long and 1.4” wide. You will see only four toes and claw marks may be seen. The two middle toes are longer. The hind foot has a similar pattern, but you will see five toes and they are about 2.2” long. Most tracks include the tail drag between the foot marks. These are quite common all over the island.

The scat is round-ish and not very long – about 2”.

Read more:

https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/UW/UW45600.pdf

https://myfwc.com/wildlifehabitats/profiles/mammals/land/armadillo/

https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/science/five-facts-nine-banded-armadillo/.

A coyote moving on Pensacola Beach near dawn.

Photo provided by Shelley Johnson.

Coyote

This is an animal that makes people nervous. They are one of the larger mammals on the beach, and they are carnivores. Attacks on pets and children are a concern for many. However, this is rarely the case. Studies show that they are actually very nervous around people and tend to stay at a distance. However, if fed cat food or available garbage, they will lose that fear and problems can occur. Like most island mammals, they are nocturnal, and diet studies have found the bulk of their meals are rodents – which is doing us a favor. But, like raccoons, they are intelligent and opportunistic. If they find an easy meal, like shorebird and turtle eggs – or the chicks and hatchlings – they will take them. It was once thought they were creatures of the American west and migrated into the eastern United States. Some scientists have found coyote remains in the eastern US that predate the ice age – so maybe they are just returning home. There are also reports of humans bringing them here for “fox hunts” – not realizing these were not fox. Either way, they are in all 67 counties of Florida, and on Pensacola Beach. They look similar to dogs – but will be thinner and their tails hang down between their legs when they run. One way to know if they are around is to listen when a siren is going – they tend to howl at these.

Their tracks are very similar to dogs and more people are bringing dogs onto the beach and into natural areas – hard to tell them apart. The pad at the rear of both the front and back paws of the coyote has three lobes, dogs have two on the front foot. In general, dog tracks are more round, coyotes typically are long and not as wide. Characteristic of dog family – the claw marks can be seen. Keep in mind that tracks are distorted in soft sand – best to look in wet sand.

The scat is also characteristic of wild canines – long and thin (like a hot dog) and tapered at each end (like a tamale). Coyote scat is usually 3-8” long and may have the characteristic claw scratching marks some dogs do.

Read more:

https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/UW/UW44300.pdf.

https://myfwc.com/conservation/you-conserve/wildlife/coyotes/.

https://myfwc.com/wildlifehabitats/profiles/mammals/land/coyote/

The Choctawhatchee Beach Mouse is one of four Florida Panhandle Species classified as endangered or threatened. Beach mice provide important ecological roles promoting the health of our coastal dunes and beaches. Photo provided by Jeff Tabbert

Beach Mouse

Beach mice are like the Loch Ness monster – everyone talks about them, but no one has seen one. Many locals have lived on this beach all of their lives and have never seen one – but they are there – and they are protected. The deal with protection is that these are isolated populations on each island. With no chance to mix genes, they have become “unique” and found no where else. There are four species in the state listed as endangered – including the nearby Perdido Key Beach Mouse and the Choctawhatchee Beach Mouse. It is believed the subspecies found on Pensacola Beach is the Santa Rosa Beach Mouse and is not listed as endangered – but is a species of concern (see list in link below). These little guys dig multiple burrows throughout the dune field but prefer those that are more open and have plenty of sea oats. They emerge at night feeding on a variety of seeds, fruits, and even insects – but sea oats are their favorite. It has been suggested they play an important role of dispersing these seeds. The introduction of new predators, and human development, have put these guys at high risk of extinction.

As you can imagine, the tracks are tiny. They are round in shape and show claw marks.

Read more:

https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/UW/UW17300.pdf.

https://myfwc.com/media/1945/threatend-endangered-species.pdf.