by Jennifer Bearden | Nov 8, 2019

Daikon Radish and Buck Forage Oats Plot

When people put in food plots and are not successful, I normally see the following three problems as possible cause. First, they didn’t consider soil pH or fertility. Second, they didn’t choose the right plant varieties for our area. Third, they didn’t manage weeds properly or at all. So following these three steps can help establish a successful food plot.

- Soil pH and fertility

Often wildlife enthusiasts ignore soil pH and fertility. If the soil pH isn’t right, fertilization is a waste of time and money. Different plants have different needs. Some plants need more phosphorus than others. Some need more iron or zinc or copper. The availability of these elements not only depends on whether they are present in the soil but also on the soil pH. Test, Don’t Guess! It takes a week or two to get the full soil sample results back and costs only $10 per sample. That’s a pretty cheap investment to insure a successful food plot.

- Variety selection

Cool season food plots are generally used as attractants for hunters. It does provide some nutrition for the wildlife as well. The goal is to select forages that are desirable to the animals as well as varieties that grow well in our area. Some great choices include: oats, triticale, clovers, daikon radish and Austrian winter peas. We recommend a blend because it extends the length of time that forages are available to the animals as well as decreased risk of food plot failure. For a more information on recommended cool season forages, go to https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/ag139.

Tetra Treat Clover Mixture Plot

- Weed management

Often tilling the food plot prior to planting is enough to manage most weeds. This is okay when you have native weeds on relatively flat land. If erosion is an issue, or if more problematic weeds such as cogongrass are present, a different weed management strategy is recommended. Glyphosate is a good choice as it is a broad spectrum herbicide that will not negatively affect the food plot. Spray the area with glyphosate 3-4 weeks prior to planting to give it time to kill the weeds. Also, remember that many herbicides are not effective during droughts, so you either need to wait until we have rainfall or work with your extension agent to find a solution that will work for your situation.

These three steps are crucial to successful food plots. First, get your soil pH right and then fertilize properly. Next, choose the right forages and varieties to plant. Then control the weeds so they don’t choke out your food plots. The next step is to enjoy this hunting season. For more information on wildlife food plots, you can contact your local county extension agent.

by Sheila Dunning | Oct 10, 2019

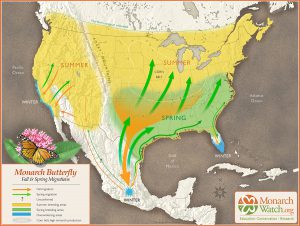

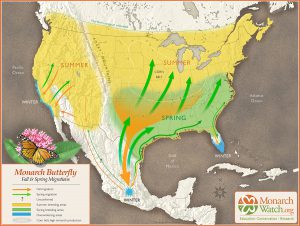

Over 1.8 million Monarch butterflies have been tagged and tracked over the past 27 years. This October these iconic beauties will flutter through the Florida Panhandle on their way to the Oyamel fir forests on 12 mountaintops in central Mexico. Monarch Watch volunteers and citizen scientists will be waiting to record, tag and release the butterflies in hopes of learning more about their migration and what the 2019 population count will be.

Over 1.8 million Monarch butterflies have been tagged and tracked over the past 27 years. This October these iconic beauties will flutter through the Florida Panhandle on their way to the Oyamel fir forests on 12 mountaintops in central Mexico. Monarch Watch volunteers and citizen scientists will be waiting to record, tag and release the butterflies in hopes of learning more about their migration and what the 2019 population count will be.

This spring, scientists from World Wildlife Fund Mexico estimated the population size of the overwintering Monarchs to be 6.05 hectacres of trees covered in orange. As the weather warmed, the butterflies headed north towards Canada (about three weeks early). It’s an impressive 2,000 mile adventure for an animal weighing less than 1 gram. Those butterflies west of the Rocky Mountains headed up California; while the eastern insects traveled over the “corn belt” and into New England. When August brought cooler days, all the Monarchs headed back south.

What the 2018 Monarch Watch data revealed was alarming. The returning eastern Monarch butterfly population had increased by 144 percent, the highest count since 2006. But, the count still represented a decline of  90% from historic levels of the 1990’s. Additionally, the western population plummeted to a record low of 30,000, down from 1.2 million two decades ago. With estimated populations around 42 million, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service began the process of deciding whether to list the Monarch butterfly as endangered or threatened in 2014. With the additional information, FWS set a deadline of June 2019 to decide whether to pursue the listing.

90% from historic levels of the 1990’s. Additionally, the western population plummeted to a record low of 30,000, down from 1.2 million two decades ago. With estimated populations around 42 million, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service began the process of deciding whether to list the Monarch butterfly as endangered or threatened in 2014. With the additional information, FWS set a deadline of June 2019 to decide whether to pursue the listing.

Scientists estimate that 6 hectacres is the threshold to be out of the immediate danger of migratory collapse. To put things in scale: A single winter storm in January 2002 killed an estimated 500 million Monarchs in their Mexico home. However, with recent changes on the status of the Endangered Species Act, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has delayed its decision until December 2020. One more year of data may be helpful to monarch conservation efforts.

Individuals can help with the monitoring and restoring the Monarch butterflies habitat. There are two scheduled tagging events in Panhandle, possibly more. St. Mark’s National Wildlife Refuge is holding their Butterfly Festival on Saturday, October 26 from 10a.m. to 4 p.m. Henderson Beach State Park in Destin will have 200 butterflies to tag and release on Saturday, November from 9 – 11 a.m. Ask around in the local area. There may be more opportunities.

Individuals can help with the monitoring and restoring the Monarch butterflies habitat. There are two scheduled tagging events in Panhandle, possibly more. St. Mark’s National Wildlife Refuge is holding their Butterfly Festival on Saturday, October 26 from 10a.m. to 4 p.m. Henderson Beach State Park in Destin will have 200 butterflies to tag and release on Saturday, November from 9 – 11 a.m. Ask around in the local area. There may be more opportunities.

There is something more you can do to increase the success of the butterflies along their migratory path – plant more Milkweed (Asclepias spp.). It’s the only plant the Monarch caterpillar will eat. When they leave their hibernation in Mexico around February or March, the adults must find Milkweed all along the path to Canada in order to lay their eggs. Butterflies only live two to six weeks. They must mate and lay eggs along the way in order for the population to continue its flight. Each generation must have Milkweed about every 700 miles. Check with the local nurseries for plants. Though orange is the most common native species, Milkweed comes in many colors and leaf shapes.

by hollyober | Oct 10, 2019

Insect pests can destroy substantial quantities of crops, prompting growers to invest heavily in pesticide use. Previ

These three common species of bats in FL, GA, and AL eat insect pests notorious for causing substantial damage to crops: the Seminole bat (Lasiurus seminolus), southeastern bat (Myotis austroriparius), and evening bat (Nycticeius humeralis) (photo credits @MerlinTuttle.org).

ous research in Texas suggested that bats could reduce pesticide costs by over a million dollars within their state, due to the bats’ fondness for pests that damage cotton. Scientists at UF/IFAS recently collected evidence locally that indicates bats are providing valuable assistance with pest reduction for many of the crops grown here too.

During spring and summer of 2018 scientists at UF clarified what the common species of bats were eating in north Florida, south Georgia, and south Alabama. We investigated 161 bats across 21 counties and found that 28% of these bats ate at least one Lepidopteran (moth) pest species, 21% ate a Coleopteran (beetle) pest, and 18% ate a Hemipteran (true bug) pest. In total, 12 different species of agricultural pest species were eaten by these bats.

The moth pests consumed by bats were:

- Green Cutworm Moth (Anicla infecta)

- Tobacco Budworm (Chloridea virescens)

- Soybean Looper (Chrysodeixis includens)

- Garden Tortrix (Clepsis peritana)

- Lesser Cornstalk Borer (Elasmopalpus lignosellus)

- Corn Earworm (Helicoverpa zea)

- Beet Armyworm (Spodoptera exigua)

- Fall Armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda)

- Red-Necked Peanutworm Moth (Stegasta bosqueella)

The beetle and true bug pests consumed by bats were:

- Hairy Fungus Beetle (Typhaea stercorea)

- Tarnished Plant Bug (Lygus lineolaris)

- Two-lined Spittlebug (Prosapia bicincta)

Three of these pests (Soybean Looper, Beet Armyworm, and Two-lined Spittlebug) were most often consumed by pregnant and juvenile bats. This is good news for growers of crops affected by these pests because you have a sound option for increasing the likelihood of bats helping control them. The trick is to provide the conditions that adult female bats like near the crops these pests feed on (e.g., soybeans, peanut, cotton, corn, sorghum, safflower). Most female bats pick a maternity roost in early spring. A maternity roost is a structure that provides warm, dry, dark conditions for female bats to sleep in during the day, and it is ultimately where they give birth to pups. When selecting a site to set up a maternity roost, female bats look for structures that are large enough to provide shelter for a large number of bats. A roomy structure can accommodate many bats, which allows the flightless pups to keep each other warm while the mothers fly in search of food at night. Installing a bat house like those shown here can provide conditions appropriate for a maternity colony, increasing your chances of having bats help control these insect pests.

Another useful strategy for enhancing pest control services by bats involves creating or maintaining structures that could serve as natural roost sites for bats. The natural structures bats prefer include large trees with cavities, dead and dying trees with peeling bark, oak trees with Spanish moss, and palm trees allowed to maintain their dead fronds. In agricultural areas and suburban areas these types of trees are often in short supply.

Maintaining large, old trees of a mix of species, and supplementing with bat houses, can help ensure there are plenty of roosting options for bats. This, in turn, will increase the likelihood that bats are available to assist with your pest management.

by Mark Mauldin | Oct 10, 2019

Protecting and promoting plants that produce soft mast, like this wild persimmon, can be a crucial step in improving wildlife habitat. Note: This time of year persimmons will be orange, the picture was taken earlier in the summer.

Photo Credit: Mark Mauldin

Landowners frequently prioritize wildlife abundance and diversity in their management goals. This is often related to a desired recreational activity (hunting, bird watching, etc.).

In order to successfully meet wildlife related management goals, landowners need to understand that animals frequent specific areas based largely on the quantity, quality and diversity of the food and cover resources available. Implementing management strategies that improve wildlife habitat will lead to greater wildlife abundance and diversity.

Herbivorous wildlife feed on plants, mostly in the form of forages and mast crops. All wildlife species have preferences in terms of habitat, especially food sources. Identifying these preferences and managing habitat to meet them will promote the abundance of the desired species.

Herbaceous plants, leaves, buds, etc. – serve as forages for many wildlife species. Promoting their growth and diversity is essential for improving wildlife habitat. Three common habitat management practices that promote forage growth include:

1) Create forest openings and edges; forested areas with multiple species and/or stand ages, areas left unforested allowing for increased herbaceous plant growth.

2) Thinning; open forest canopy allowing more light to hit the ground increasing herbaceous plant growth and diversity.

3) Prescribed fire; recycle nutrients, greatly improve the nutritional quality of herbage and browse, suppress woody understory growth.

Mast – the seeds and fruits of trees and shrubs – is often one of the most important wildlife food sources on a property.

Hard mast includes shelled seeds, like acorns and hickory nuts and is generally produced in the fall and serves as a wildlife food source during the winter.

Soft mast includes fruits, like blackberries and persimmons, and is generally produced in the warmer months, providing vital nutrition when wildlife species are reproducing and/or migrating.

Making management decisions that protect and promote mast producing trees will encourage wildlife populations.

Landowners can make supplemental plantings to increase the quantity and quality of the nutrition available to wildlife. These supplemental plantings (food plots/forage crops and mast producing trees) can be quite expensive and should be well planned to help maximize the return on investment.

Key points to remember to help ensure the success of supplemental wildlife plantings.

- Select species/varieties that are well adapted to the site.

- Take soil samples and make recommended soil amendments prior to planting.

- Make plantings in areas already frequented by wildlife (edges, openings, etc.).

- Food plots should be between 1 and 5 acres. Long, narrow designs that maximize proximity to cover are generally more effective.

Habitat management and other wildlife related topics are being featured this year in the UF/IFAS building at the Sunbelt Ag Expo. Make plans to attend “North America’s Premiere Farm Show” and stop by the UF/IFAS building, get some peanuts and orange juice and learn more about Florida’s Wildlife.

If you have any questions about the topics mentioned above, contact your county’s UF/IFAS Extension Office or check out the additional articles listed on the page linked below.

If you have any questions about the topics mentioned above, contact your county’s UF/IFAS Extension Office or check out the additional articles listed on the page linked below.

EDIS – Wildlife Forages

A significant portion of this article was summarized from Establishing and Maintaining Wildlife Food Sources by Chris Demers et al.

by Rick O'Connor | Mar 29, 2019

We have a lot of really cool and interesting creatures that live in our bay, but one many may not know about is a small turtle known as a diamondback terrapin. Terrapins are usually associated with the Chesapeake Bay area, but actually they are found along the entire eastern and Gulf coast of the United States. It is the only resident turtle of brackish-estuarine environments, and they are really cool looking.

The diamond in the marsh. The diamondback terrapin.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

Terrapins are usually between five and 10 inches in length (this is the shell measurement) and have a grayish-white colored skin, as opposed to the dark green-black found on most small riverine turtles in Florida. The scutes (scales) of the shell are slightly raised and ridged to look like diamonds (hence their name). They are not migratory like sea turtles, but rather spend their entire lives in the marshes near where they were born. They meander around the shorelines and creeks of these habitats, sometimes venturing out into the seagrass beds, searching for shellfish – their favorite prey. Females do come up on beaches to lay their eggs but unlike sea turtles, they prefer to do this during daylight hours and usually close to high tide.

Most folks living here along the Gulf coast have not heard of this turtle, let alone seen one. They are very cryptic and difficult to find. Unlike sea turtles, we usually do not give them a second thought. However, they are one of the top predators in the marsh ecosystem and control plant grazing snails and small crabs. During the 19th century they were prized for their meat in the Chesapeake area. As commonly happens, we over harvested the animal and their numbers declined. As numbers declined the price went up and the popularity of the dish went down. There was an attempt to raise the turtles on farms here in the south for markets up north. One such farm was found at the lower end of Mobile Bay.

Early 20th century still found terrapin on some menus, but the popularity began to wane, and the farms slowly closed. Afterwards, the population terrapins began to rebound – that was until the development of the wire meshed crab trap. Developed for the commercial and recreational blue crab fishery, terrapins made a habitat of swimming into these traps, where they would drown. In the Chesapeake Bay area, the problem was so bad that excluder devices were developed and required on all crab traps. They are not required here in Florida, where the issue is not as bad, but we do have these excluders at the extension office if any crabber has been plagued with capturing terrapins. Studies conducted in New Jersey and Florida found these excluder devices were effective at keeping terrapins out of crab traps but did not affect the crab catch itself. Crabs can turn sideways and still enter the traps.

This orange plastic rectangle is a Bycatch Reduction Device (BRD) used to keep terrapins out of crab traps – but not crabs.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Another 20th century issue has been nesting predation by raccoons. As we began to build roads and bridges to isolated marsh islands in our bays, we unknowingly provided a highway for these predators to reach the islands as well. On some islands, raccoons depredated 90% of the terrapin nests. Today, these turtles are protected in every state they inhabit except Florida. Though there is currently no protection for the terrapin itself in our state, they do fall under the general protection for all riverine turtles; you may only possess two at any time and may not possess their eggs.

Some scientists have discussed identifying terrapins as a sentinel species for the health of estuaries. Not having terrapin in the bay does not necessarily mean the bay is unhealthy, but the decline of this turtle (or the blue crab) could increase the population of smaller plant grazing invertebrates they eat throwing off the balance within the system.

Sea Grant trains local volunteers to survey for these creatures within our bay area. Trainings usually take place in April and surveys are conducted during May and June. This year we will be training volunteers in the Perdido area on April 10 at the Southwest Branch of the Pensacola Library on Gulf Beach Highway. That training will begin at 10:00 AM. For Pensacola Beach the training will be on April 15 at the Navarre Beach Sea Turtle Conservation Center on Navarre Beach. That training will begin at 9:00 AM. A third training will take place on April 22 at the Port St. Joe Sea Turtle Center in Port St. Joe. For more information on diamondback terrapins contact me at the Escambia County Extension Office – (850) 475-5230 ext. 111.

by hollyober | Mar 20, 2019

A prescribed fire burns safely in a natural area. Photo by Holly Ober.

Most plant and wildlife communities in Florida are adapted to periodic fires. For thousands of years, fires were ignited naturally, and frequently, by lightning. In fact, Florida has the greatest number of lightning strikes of any state in the country. About 1,000 lightning-set fires are documented in Florida each year.

Today, due to the many people living in Florida, the vast majority of fires naturally ignited by lightning are quickly suppressed by trained personnel. This is done to reduce the loss of human life and property. Although helpful to human safety in the short term, suppression of fire from natural areas for long periods of time can be problematic for all the native plant communities and wildlife that are adapted to periodic fire, and ultimately dangerous for humans as well. The longer our natural areas go unburned, the greater the accumulation of vegetative material that could serve as fuel for fire, and the greater the possibility of uncontrollable wildfires devastating natural areas, homes, and buildings when lightning strikes.

PRESCRIBED FIRES are an important tool: they are a safe alternative to wildfires. Prescribed fires are intentionally set under favorable weather conditions with the goal of stimulating the ecological benefits produced by natural wildfires. By selecting safe conditions for these burns and by preparing for them in advance by creating barriers to halt the spread of fire past desired borders, trained personnel have much more control over the results of these fires. The reason we often see and smell smoke in the spring is because this is the most popular time of year to use prescribed burning as a forest management tool.

Below are some of the benefits fire provides to the health of the many plants and wildlife that naturally occur in our state.

- Fire maintains required habitat conditions for many of Florida’s plant and wildlife species.

- Fire promotes fruit production of many woody plant species.

- Fire promotes flowering of herbaceous (non-woody) plant species.

- Fire promotes diverse herbaceous plants that serve as food for insects and wildlife.

- Fire scarifies seeds, breaking down their hard seed coats and promoting germination.

- Fire prepares sites for seeding or planting of species that require bare mineral soil.

- Fire creates growing conditions required by some cone-bearing trees. It reduces leaf litter on the soil surface, increases nutrient reserves, and canopy openings so that sunlight can reach the forest floor.

- Fire releases nutrients bound up in dead organic matter, ultimately increasing palatability, digestibility, and nutritional value of growing plants for wildlife.

- Fire can improve the quality of forage for grazing livestock.

- Fire changes the density of trees in the forest, creating space for some wildlife species.

- Fire removes hardwood thickets and vines in the understory of pine forests, making these areas more suitable for some wildlife species.

- Fire controls insect pests and diseases that afflict pine trees.

- Fire increases the rate of nutrient cycling of some elements and elevates soil pH.

- Fire creates a diverse habitat conditions when fires are patchy, leaving pockets of unburned areas.

- Fire reduces the risk of severe, high intensity wildfires that could cause harm to native plants and wildlife by preventing the accumulation of highly-flammable, dead vegetation.

The last week in January has been designated as Prescribed Fire Awareness Week in Florida. Early February has been designated as Prescribed Fire Awareness Week in Georgia. March is Prescribed Fire Awareness Month in South Carolina. Why are so many southern states making a big deal about prescribed fire? It is because we have recognized the importance of safe fires for both the health of our native plants and wildlife as well as the safety of our human residents and visitors. If you see or smell smoke in a nearby natural area, it might well be coming from a prescribed fire intended to benefit our natural plants and wildlife as well as our safety.

To learn more about prescribed burning in Florida, visit https://www.freshfromflorida.com/Divisions-Offices/Florida-Forest-Service/Wildland-Fire/Prescribed-Fire