by Rick O'Connor | Mar 2, 2022

Early Detection Rapid Response (EDRR)

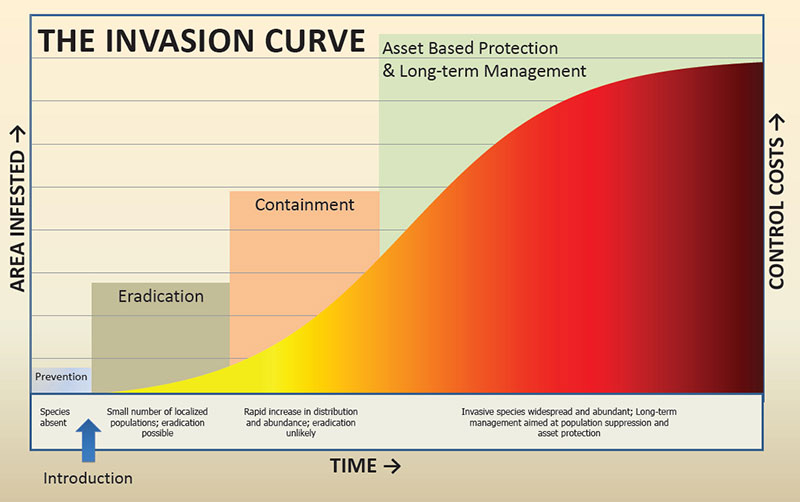

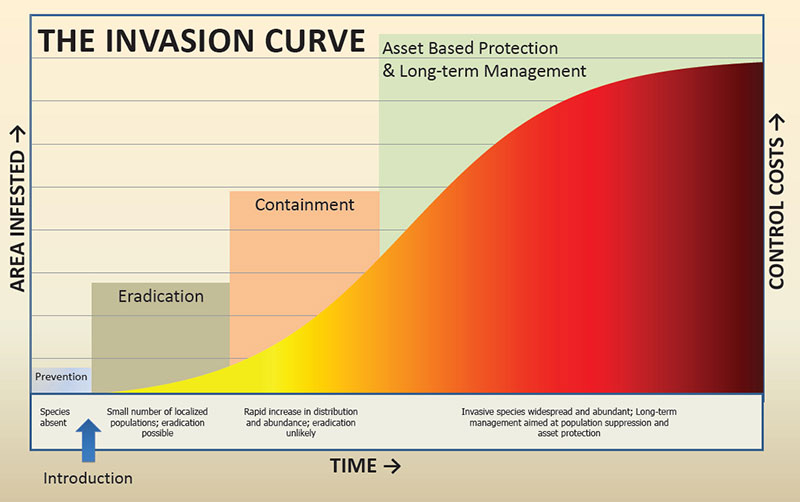

To understand better what this is you can look at the graphic below of the “invasive species curve”.

You will notice that across the x-axis is time, increasing from left to right. On the y-axis you have area covered on the left and control costs on the right. You will notice the longer you allow an invasive species to go unchecked in your community, the more it will spread, the more it will cost to manage, and you will reach a point where eradication is no longer an option. As a matter of fact, if you are serious about eradication, you will need to manage this species in the early stages of the invasion.

We have mentioned in previous articles the cost of managing invasive species. Annually, the U.S. spends about $120 billion doing this. If you want to reduce these costs, and avoid the problems these species bring with them, you need to identify and remove them from the landscape early in the invasion.

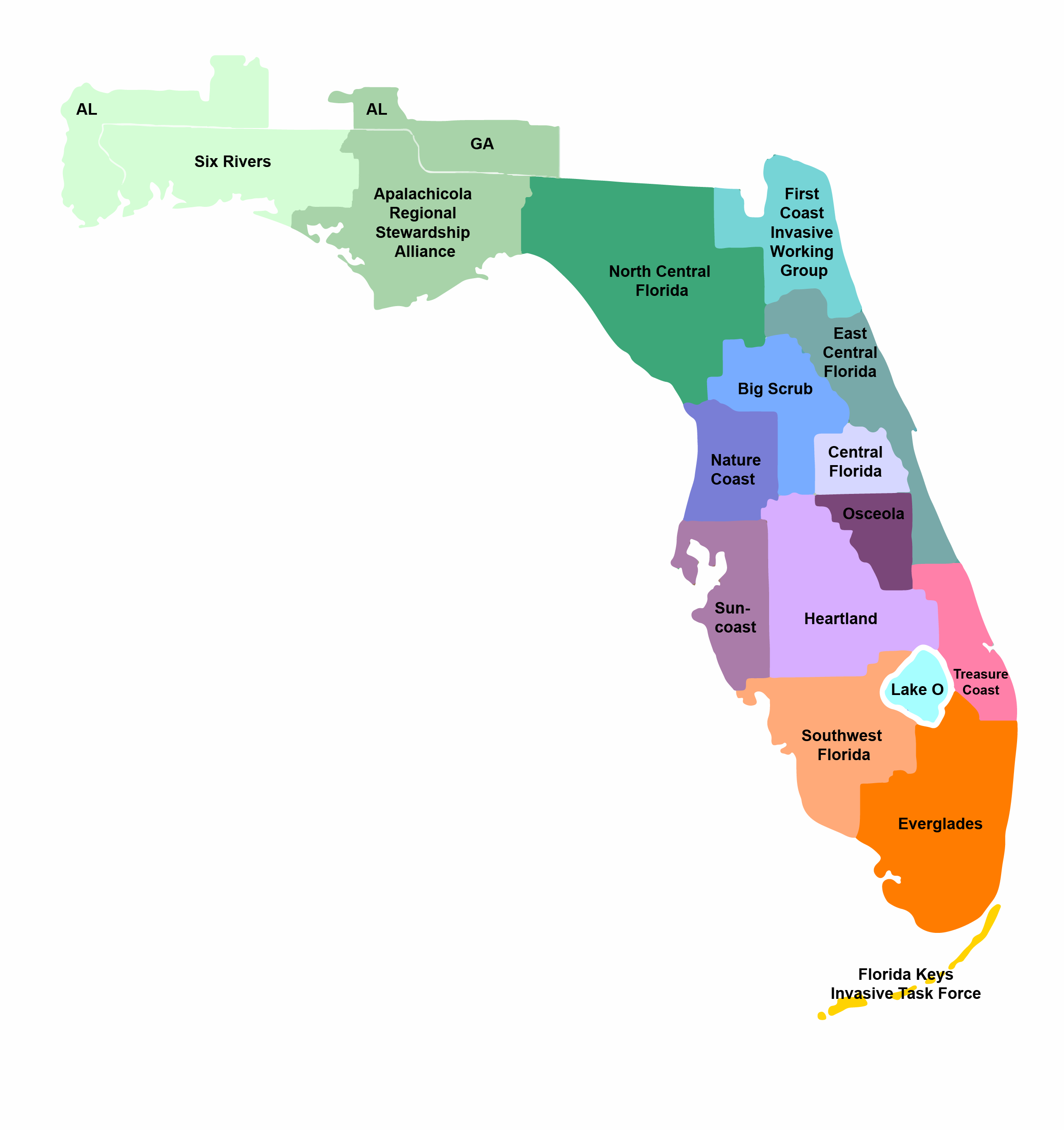

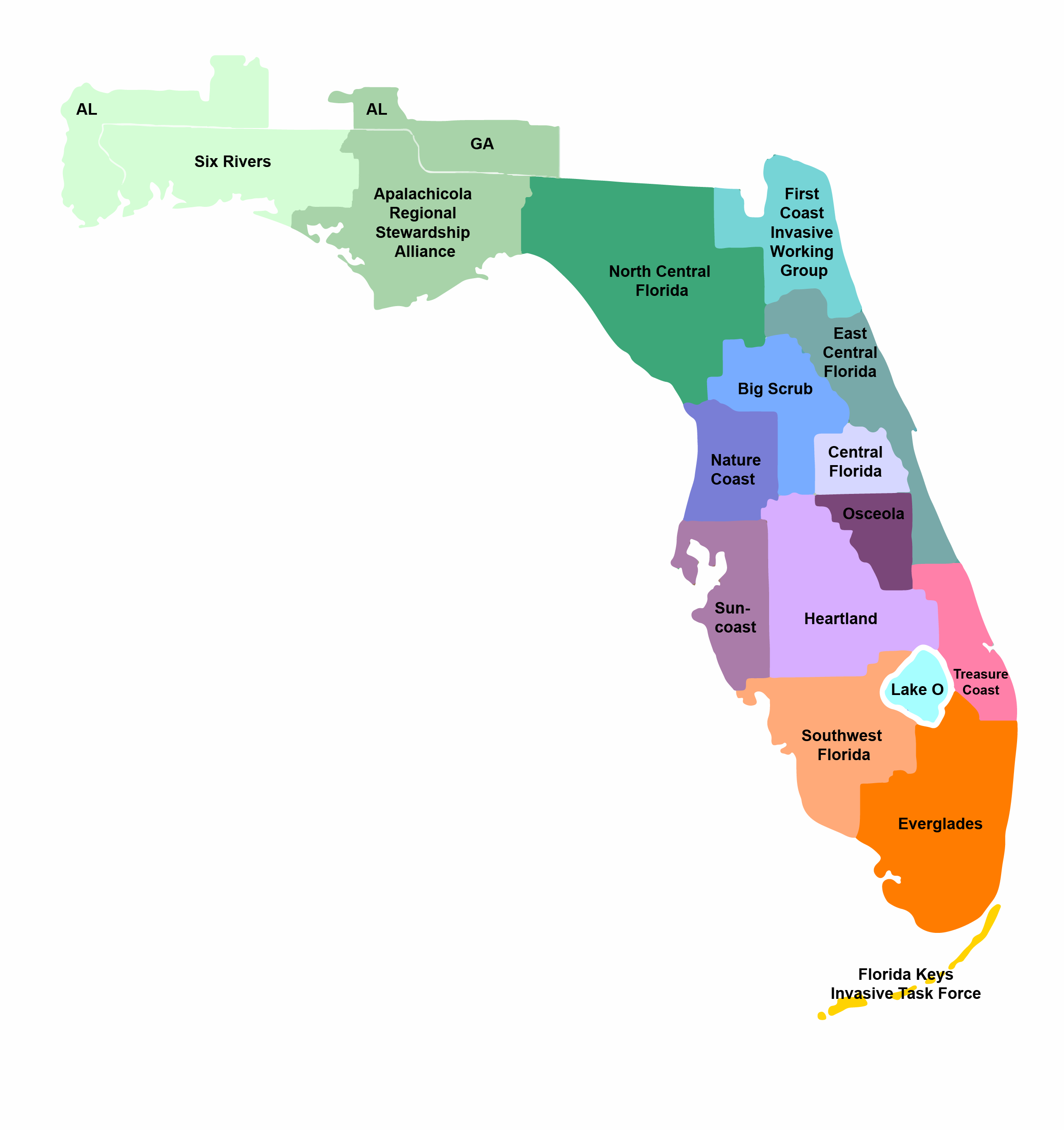

Florida CISMAs

Early Detection Rapid Response (EDRR) species are those that are not present in your community but are in nearby ones or are in your community but in very low numbers. You will see step 1 in the curve is to prevent the species from reaching you. The state of Florida is divided into 15 Cooperative Invasive Species Management Areas (CISMAs) where professionals within manage and educate the public about invasive species. One method of detecting a potential EDRR species is to see what nearby CISMAs are dealing with. You can find records of these species by searching EDDMapS, a national invasive species database (www.EDDMapS.org). Often the records are under reported and the actual number within/near your CISMA is higher. At that point you can educate your community about them and possibly prevent them from entering your CISMA. Likewise, if they are already within your CISMA in low numbers, it would be considered an EDRR species and action should be taken now.

Here in the western panhandle, we belong to the Six Rivers CISMA, which includes three counties in Alabama. During the shutdown of the pandemic, we were able to update our EDRR list and are currently developing fact sheets for each. Here is our EDRR list – it is in no particular order.

- Eurasian milfoil. This is an aquatic weed that was introduced via the aquarium trade. There are currently 12 records within Six Rivers and 12 in the eastern panhandle for a total of 24 records. There is quite a lot of this plant in the Mobile Delta area.

- Beach vitex. This is a beach/dune vine that eventually becomes a shrub. There are currently 83 records within the CISMA and five in the eastern panhandle for a total of 88 records. Almost all of the records are from the Pensacola Beach area.

- Argentine Black and White Tegu. This is a 3–4-foot lizard from South America that has caused a lot of problems in central and south Florida. There are seven records within Six Rivers and seven more from the eastern panhandle for a total of 14 records. There is no evidence of breeding populations here. It is believed these are escaped pets. One escape was from a breeder in the western panhandle, but all animals were captured but we keep an eye out.

- Callery (Braford) Pear. This is an ornamental tree that many have purchased and planted. There are 169 records within Six Rivers and another five in the eastern panhandle for a total of 174 records. This is most likely from better reporting in the Six Rivers, much of it coming from the Blackwater Forest area, where it is under management.

- Cane Toad. This is a large toad that produces a strong toxin that has killed dogs. It is a much larger problem in central and south Florida but there is one record within Six Rivers and another in the eastern panhandle for a total of two. Though there was a question on identification of the one within Six Rivers, it was eventually verified. Like the tegu, there is no evidence of breeding populations here, but we keep watch and remove if found.

- Channeled Apple Snail. This species is famous for the problems it has caused with the snail kites in central and south Florida. There are no records of it in Six Rivers and only two in the eastern panhandle, but it is feared that this species may be more common than the records suggest.

- Coral ardisia. This is a beautiful plant that produces beautiful red berries but is a problem. It takes over patches in hardwood habitats and has invaded natural areas. There are 14 records within Six Rivers and 407 in the eastern panhandle for a total of 421 records. This plant may have originally escaped cultivation in the eastern panhandle hence the high numbers there.

- Cuban Treefrog. This is a large treefrog that consumes all others, as well as other forms of wildlife. There are 13 records within Six Rivers and 19 in the eastern panhandle for a total of 32 records. There has been increasing number of reports from the Six Rivers CISMA suggesting that this is a species that needs immediate attention.

- Giant Salvinia. This is floating plant that resembles duckweed, but the leaves are larger. There are 10 records within Six Rivers and two more in the eastern panhandle. These are the only known records of this plant in the entire state. Those within Six Rivers are in Bayou Chico. There is an effort by FWC to eradicate this plant, but public help is needed.

- Green Mussel. This is a beautiful emerald, green mussel that grows in clumps on pilings and rocks in marine waters. There is only one record within Six Rivers and no records from the eastern panhandle. The lone specimen was found in Pensacola but was not verified. It is a problem in peninsula Florida so keeping an eye out for it is smart.

- Greenhouse Treefrog. This is a very small treefrog that has been found in local gardens. There are five records from Six Rivers and two others from the eastern panhandle for a total of seven records, but it is believed to be more common than this.

- Guinea Grass. There are 18 records of this plant within Six Rivers and five additional from the eastern panhandle for a total of 23 records.

- Hydrilla. This is another aquatic grass brought in for the aquarium trade. There are eight records within Six Rivers and 28 from the eastern panhandle for a total of 36 records. This is a big problem in the peninsula part of the state, and we spend a lot of money controlling it.

- Natal Grass. This is a wiry grass that grows in more open fields and has a pretty tuft of small red flowers at the top giving the landscape an interesting reddish look – but it is invasive and needs to be controlled. There are 31 records from Six Rivers and 21 more from the eastern panhandle for a total of 52 records.

- Skunk Vine. There is only one record within Six Rivers, but this is probably under reported. There are an additional 16 records from the eastern panhandle for a total of 17 records.

- The Snail. It is called “the snail” because no common name has been given. The scientific name is Bulimulus sporadicus and it appears to have been introduced in the Jacksonville area. From there the snail seems to have followed the railroad lines, possibly from cargo, and has begun to spread. There are no official records from EDDMapS from the Florida panhandle, but it has been found by many gardeners. More needs to be learned about this potential threat and more records are needed.

- Swamp Morning Glory. This is an aggressive growing vine that has been problematic for property owners who have it. Currently, there are only two records from Six Rivers and no records from the eastern panhandle, but this is probably another under reported species.

- Water Hyacinth. This is a well-known floating plant with beautiful purple flowers. But it will overtake waterways quickly changing the entire ecosystem and potential hampering economic opportunities within those waterways. There are 21 records within Six Rivers and 256 in the eastern panhandle for a total of 277 records.

These are the EDRR species for our area. As mentioned, they are under reported and help is needed to improve this. Help is also needed in preventing the spread of them. Cleaning equipment, like tractors, ATVS, and boats before moving is a good start. Being mindful of what you purchase at the store, and what may be “hitchhiking” on it is another good practice to help. And, if you do find on your property, reporting and removing it will also help.

If you have questions about identification and safe methods of removal, contact your county extension office. Tomorrow we will look at the “Dirty Dozen” invasive species for the Florida panhandle.

by Rick O'Connor | Mar 1, 2022

Based on the definition we use for an invasive species, they got here because of us. It may have been unintentional, but it was still humans who assisted their arrival.

Each species has a biogeographic range.

All species have a biogeographic range. There is some point of origin, where they first appeared, and then a dispersal process as their populations moves across the landscape. Dispersal is driven by competition, usually with your own species, but can be with others as well. If there is no longer food or space for the number in the population, they move to new territory – dispersal. This dispersal continues until they encounter some sort of barrier, something that stops dispersal. Barriers can be physical, like a river or mountain range. They can be biological, like the lack of their needed food or the presence of a new predator that you have no defense against. They can be climatic; it is now too cold or too hot. Whatever it is, it stops dispersal, and the species now has its geographic range.

Mountains and rivers can be barriers to species dispersal.

Kangaroos and wallabies are isolated on an island we call Australia. Australia is very large, and the physical features and climate vary so, kangaroos are not found over the entire continent. Many of the plant and animal species that originated in Asia would have a difficult time reaching North America. Many birds have few physical barriers because they can fly over most of them. But their dispersal can still be impeded by biological or climatic barriers. Species that have very large ranges are called cosmopolitan, like seagulls. Species with small ranges are referred to as endemic species, like the marine iguana of the Galapagos.

Islands can be difficult for many species to reach.

For invasive species then, we are talking about those that would have a very difficult, if not impossible time, reaching Florida – but did so because we brought them here, we got them past their natural barriers.

In many cases this is intentional. In the early history of Key West, it was the home of many sea captains who often brought exotic plants from around the world to plant in their yards. Banyan trees for example, are not native to Florida, but are found in Key West. Orange trees were introduced by us, as were thousands of ornamental plants for landscaping, and sugar cane for agriculture. Most of these would not have found their way to our shores without us.

Nurseries provide native and nonnative plants.

And there were many animals that reach Florida because we intentionally brought them. Horses, pigs, cattle to name a few. There are of course exotic pets like boas, monitor lizards, and tropical fish. There are reports of some coyotes being introduced for the purpose of hunting, though we know that coyotes dispersed into Florida naturally as well.

And then there are those that reached us due to hitchhiking. We load cargo on ships, trucks, and planes from all over the world and deliver them to new destinations like Florida. As a matter of fact, Florida and Hawaii are two states with large invasive problems because of the amount of international traffic (planes and ships) and a subtropical climate that is suitable to many of them.

Nonnative species can be transported on ships and in their ballast.

Most of the Polynesian islands are very isolated and difficult for species to reach. During World War II the brown tree snake was accidentally dispersed by the U.S. Navy as they battled their way across the islands trying to reach Japan. On the island of Guam there are reported 20,000 snakes for each human on the island and no predators to control them. Hawaii is so concerned about this issue that all aircraft coming from that part of the world are isolated on a runway at the airport until a thorough check can be conducted, often using dogs. When I traveled there years ago, we had to complete a form asking if we were bringing any plants? Was their soil with the plants? If you had dogs, they had to be quarantined because there were no ticks on the island. And, like Guam, there are no native snakes on the island as well. I heard one story where a local on the Oahu decided to raise piranha, I suppose as a deterrent. The fish were confiscated, and the project destroyed.

Firewood is now something biologist are concerned about. There has been an issue in many forest with insects that either eat the trees directly or make them weak and susceptible to diseases. Many campers like to gather firewood for camp and will take logs with them to their next camp in the next state, not knowing they are spreading the problem.

Campers can move species by carrying firewood with them to each new site.

Boating has been known to spread invasive plants. Launching and recovering your boat, the trailer may grab some plant, you move to the next lake an – wah-lah. This has become such a big issue out west that many lakes have check in stations where officers check your boat and trailer as you arrive AND when you leave – a point made in the last article, we are spending a lot of money on battling invasive species.

The Great Lakes area has a large problem with invasive species that are transported more by shipping. There are several major ports in this region. Ships carrying cargo have weight to make them stable when in rough seas. However, when they empty that cargo at port, they become light and the trip back could be a bit precarious. To offset the weight loss, they will add ballast. In the colonial period, this would have been stones from the surrounding area. The ships would unload the cargo, load the ballast, sail to their next destination, unload the blast (you have now moved this and whatever it was carrying), and get a new load of cargo – and so, it goes. Today ships use water as ballast. As a ship enters a port in the Great Lakes, they may discharge their ballast tanks of water they took on in another part of the world. Sometimes releasing things like zebra mussels.

Florida of course is no different than any of these other stories. International travel lands at our airports and cruise ship ports everyday bringing who knows what. Campers come from around the country harboring a variety of unknown hitchhikers. And then there are the intentional exotic plants and animals shipped in for the pet and landscaping industries.

Keep in mind that not all nonnative species are invasive. To labeled them so they would need to be causing a problem. Red fire ants entered the U.S. accidentally through the port of Mobile, Alabama. They have been a real problem wherever they have been found, they have been labeled invasive. But there are plenty of nonnative plants and animals that have not been problematic. Banyan trees may not be causing any real problem and thus would not be labeled invasive. You can say the same for many other nonnative plants.

The problem we have is that some have “escaped” – coral ardisia, Brazilian pepper, Burmese pythons, have been found to be a problem and knowing which will be problems and which will not is tough. You really won’t know until they have spread, and the issue arises.

The Burmese python.

Photo: University of Florida

For us Miami is “ground zero” for such problems. It is a tropical international hub. There are numerous invasive species that entered our state here and have spread across central and south Florida. North Florida has fewer due to our climate, but we are finding (a) many species can tolerate our climate and are doing well – cogongrass, Chinese tallow, Chinese privet – and (b) our climate is warming allowing species that were once not a threat, to become one.

I’ll finish on a story from college. I was attending the University of Southern Mississippi. My roommate was from Afton, Wyoming. Unknown to him, he carried cockroaches’ home in his luggage one semester. This is an animal not found in the Rockies, it now lived in his house. It is very easy for us to carry hitchhikers across wildlife barriers. We will discuss how to prevent this in a later article, but up next will be an article discussing some of the new species that may threaten the Florida panhandle.

by Rick O'Connor | Feb 28, 2022

In recent years this question has come up more often. With the thousands of different invasive species taking over the landscape and waterways why are we spending so much time, money, and resources battling them when you are not going to win? It’s a fair question honestly and one that is the theme of the 2016 book The New Wild by science writer Fred Pearce.

The argument that Pearce makes is that life on our planet has worked under the premise that the stronger survive and pass on their genes to the next generation since the beginning of time. They compete with other species for space and resources and those best adapted will win out. If these invasive species are winning out, that is how nature intended it to be and that we should get use to the “new wild”.

Under this thought the forest of the southeastern United States would hold more Chinese tallow and cogongrass than it once did, and the reefs of the Gulf of Mexico would be home to a new species called the lionfish. Again, the thought makes sense and indirectly may be growing.

I say that because there are many who cannot euthanize an animal, no matter who it is or where it came from. There is a growing call to not euthanize them because it is wrong, and even some cases with green iguanas where rescues, and releases, from the cold are now occurring. There are some who found economic ways to benefit from some invasive species, lionfish dinners and Chinese tallow honey, and do not necessarily want to remove them. So, maybe these nonnative species are not all that bad.

So, why should we be concerned about them?

Why should spend the time, money, and effort to manage them (euthanizing when needed)?

Well, by using the definition accepted by the University of Florida IFAS Extension, they are bad. This definition states (1) invasive species are non-native to the area, (2) they arrived via humans (whether intentional or accidental), and (3) they are causing an economic and/or environmental problem. Lowering your quality of life has also been connected to a “problem”. And if it is truly a problem, and it should be to have the name invasive attached, then it needs to be managed. If they are not really causing a problem, then maybe they are not really invasive.

With invasive species we typically see a nonnative who moves into a disturbed part of the environment. Being nonnative, they have few natural predators, and their reproductive dispersal of the landscape is quick and effective. They have mentioned that the dispersal rate of the lionfish was one of the greatest “invasions” ever seen. This increase in their population decreases the populations of native species and, in many cases, the overall biodiversity of the system. Biologists and naturalists understand the importance of biodiversity in maintaining a healthy ecosystem. Monocultures of any species, even in agriculture, and be dangerous when a pathogen comes along. This pathogen could wipe out the entire ecosystem. I have heard this argument before. Most of the Everglades is sawgrass, sawgrass is grass, which provides food and oxygen for the rest of the system. If herbivores only need plants to survive, and they provide food for the carnivores, does it really matter which grass it is? Grass is grass.

However, if this grass species does become threatened by a pathogen, or the herbivores do not eat such grass, then we DO have a problem. The invasion of cogongrass is a good example of this. With the serrated blades and layers of silica within, few herbivores seek this plant out. If cogongrass is allowed to take over forest and farmland, there is certainly a problem, and this plant would need management.

Deep water lionfish traps being tested by the University of Florida offshore Destin, FL. [ALEX FOGG/CONTRIBUTED PHOTO]

Lionfish is no different. There are some reefs in the northern Gulf of Mexico that have had densities of 200 lionfish/hectare or more. Some photos show only lionfish. Studies show they are like bullfrogs, consuming anything they can get into their mouths. There are at least 70 different species of small reef fishes that have been found in the stomachs of lionfish. The decrease of these small fish can impact the presence of larger, commercially sought-after species. They have also found that many of these small reef fish control algae growth on coral reefs and their decline can increase algae populations and the smothering of the coral themselves. They are indeed a problem.

We could go on and on with examples of how these species are problematic. Pythons, tegus, and Old-World Climbing Fern. There are those who cause problems in small quite ways such as the crazy ants, Cuban treefrogs, and the red fire ant.

And then there is the argument that WE, not nature, introduced this species. That is #2 of the definition. The argument that if nature introduced the species, then yes – we could except their presence as more natural and the process more natural. But nature did not introduce them – we did. This brings up the argument that the situation is more unnatural and since we “did it” we should “fix it”.

Even Pearce mentions in his book that some species need management. The argument that you are not going to win is true for some species. We are not going to eradicate Chinese tallow, cogongrass, and lionfish from Florida. However, we should be concerned about them. We should manage the locations where they currently exist and prevent the spread to new locations. In our next edition, we will discuss “how they get here” to help reduce the spread of current invasive species, and the introduction of new ones, from happening.

by Rick O'Connor | Feb 24, 2022

EDRR Invasive Species

Cane Toad (Rhinella marina)

a.k.a Bufo toad, Marine toad

The Cane Toad

Photo: University of Georgia

Define Invasive Species: must have ALL of the following –

- Is non-native to the area, in our case northwest Florida

- Introduced by humans, whether intentional or accidental

- Causing either an environmental or economic problem, possibly both

Define EDRR Species: Early Detection Rapid Response. These are species that are either –

- Not currently in the area, in our case the Six Rivers CISMA, but a potential threat

- In the area but in small numbers and could be eradicated

Native Range:

The cane toad is native to central and south America.

Introduction:

Cane toads were intentionally released into Florida in the 1930s as a biological control for a beetle that was consuming the economically important sugar cane crop. It is believed that the initial released population did not survive but additional released toads in the 1950s did.

EDDMapS currently list 1,102 records of this toad. All but five are reported from Orlando south. Three were reported in north Florida – one in the Gainesville area, one in the Villages, and one in Deltona area. Two have been reported in the Florida panhandle. A small population existed in Bay County for a period and one report came from Okaloosa County, which is the only report within the Six Rivers CISMA. This toad is still sold in pet stores, and it is most likely these were escaped pets.

Description:

This toad is much larger than our native toads. Florida’s native toads do not reach lengths greater than 4 inches, cane toads can reach 6 inches and possibly up to 9 inches. The are reddish-brown in color and have very large parotid glands (poison glands) on their shoulders. Native toad parotoid glands are typically oval in shape, the cane toads are triangular. The cane toad also possesses a ridged crest over the eye that our native toads lack.

Even in their native range, cane toads prefer human habitations and are often found around homes, gardens, schools, and in agriculture fields.

Issues and Impacts:

There are two primary concerns with this toad. (1) their voracious appetite, and (b) their toxicity to pets. Cane toads will feed on native frogs, lizards, snakes, small mammals, and anything else they can get into their mouths. In areas where cane toads are common, declines of the native southern toads have been reported. The poison secreted by this toad is highly toxic to pets. Though in most cases there is a lot of foaming and drool at the mouth, dogs have had seizures and have gone into cardiac arrest, even dying. The eggs and tadpoles of this toad are also toxic. Eggs laid in landscaped ponds typically kill the fish that inhabit them. The toxin is also highly irritable to humans. Wiping on the face or open cuts can lead to skin irritations and everyone should avoid wiping their eyes. It is recommended to handle these toads with gloves.

Management:

Hand capturing, using gloves, and humanely euthanizing cane toads found in your yard is the primary method of control. It is important to correctly identify the toad before euthanizing it. If you have questions, you can contact your county extension office.

To humanely euthanize wipe, or spray, benzocaine or lidocaine on the lower belly. This will act as an anesthesia to numb the nervous system and put the animal to sleep. The toad can now be placed in a zip lock bag and placed in the freezer. If you do not have products with benzocaine or lidocaine (often found in products to help with toothache or sunburns) you can place the toad in a zip lock bag for a few hours in the refrigerator, then move to the freezer. It is recommended if cane toads are present in your neighborhood to remove outdoor pet food and water bowls. If you do not wish to euthanize the toad you can contact a wildlife control business.

Please report any sighting to www.EDDMapS.org. There are biologists who verify the photograph you send. It is important that we keep track of this EDRR species.

For more information on this EDRR species, contact your local extension office.

References

Johnson, S. 2020. Florida’s Frogs and Toads. University of Florida Department of Wildlife Ecology. https://ufwildlife.ifas.ufl.edu/frogs/canetoad.shtml.

Wilson, A., Johnson, S. 2021. The Cane or “Bufo” Toad (Rhinella marina) in Florida. Electronic Data Information System publication #WEC387. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/UW432.

Early Detection and Distribution Mapping System (EDDMapS)

https://www.eddmaps.org/

Six Rivers CISMA

https://www.floridainvasives.org/sixrivers/

by Rick O'Connor | Feb 18, 2022

Six Rivers “Dirty Dozen” Invasive Species

Japanese Honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica)

Japanese Honeysuckle

Photo: University of Florida

Define Invasive Species: must have all of the following –

- Is non-native to the area, in our case northwest Florida

- Introduced by humans, whether intentional or accidental

- Causing either an environmental or economic problem, possibly both

Define “Dirty Dozen” Species:

These are species that are well established within the CISMA and are considered, by members of the CISMA, to be one of the top 12 worst problems in our area.

Native Range:

Japanese honeysuckle is native to China, Japan, and Korea.

Introduction:

Japanese honeysuckle was first introduced to Florida in 1875 for agricultural and gardening purposes. It was introduced as a forage plant in the agriculture industry and was very popular as a landscape plant due to its beautiful showy flowers. Its invasive nature was quickly discovered and is now listed as a Category I invasive plant and a Florida noxious weed.

EDDMapS currently has 115,101 records of this plant across the country. Most are east of the Mississippi River but cover the entire east coast, including New England. There are records in the southwestern part of the U.S. In Florida, most of the records are in the northern part of the state, particularly in the panhandle. There are few records south of Orlando. Within the Florida panhandle there are 1,558 records and 1,209 within the Six Rivers CISMA. As with most species, this is probably underreported.

Description:

Japanese honeysuckle is a woody vine that produces beautiful white flowers. These flowers have multiple sepals, and the stamens which extend outward resembling “whiskers”. The leaves are about 1-3 inches, ovate is shape, and opposite on the stem. The small fruits are green and hard when immature, black and soft when older.

Issues and Impacts:

This is an aggressive growing vine that can quickly take over the landscape. It can cover small shrubs and trees killing them, block sunlight so germination of other plants is impossible, and outcompete native plants for needed sunlight decreasing the biodiversity within the area.

Management:

Removing by hand or shovel is effective on small patches. Mowing small patches has found to reduce seed spread but the parent plant may return with additional stems. Mechanical tillage can be effective but can enhance seed dispersal from the seed bank and is not always an option in some locations.

Chemical treatment with either glyphosate or triclopyr has been effective however, cut stump application is recommended. Foliar sprays that do not reach ALL leaves can induce resprouting.

There are no known biological controls at this time.

For more information on this Dirty Dozen species, contact your local extension office.

References

Japanese Honeysuckle. University of Florida IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants

https://plants.ifas.ufl.edu/plant-directory/lonicera-japonica/.

Lonicera japonica. University of Florida IFAS Assessment. https://assessment.ifas.ufl.edu/assessments/lonicera-japonica/.

Early Detection and Distribution Mapping System (EDDMapS)

https://www.eddmaps.org/

Six Rivers CISMA

https://www.floridainvasives.org/sixrivers/

by Rick O'Connor | Feb 11, 2022

EDRR Invasive Species

Natal grass (Melinis repens)

Natalgrass

Photo: University of Florida IFAS

Define Invasive Species: must have ALL of the following –

- Is non-native to the area, in our case northwest Florida

- Introduced by humans, whether intentional or accidental

- Causing either an environmental or economic problem, possibly both

Define EDRR Species: Early Detection Rapid Response. These are species that are either –

- Not currently in the area, in our case the Six Rivers CISMA, but a potential threat

- In the area but in small numbers and could be eradicated

Native Range:

South Africa

Introduction:

Intentionally introduced as a forage plant but lacks the nutritional value of other introduced forage plants.

EDDMapS currently list 3,923 records of this plant, all are across the southern United States from California to Florida. 3,591 reports are from Florida itself, with 53 of these in the Florida panhandle, and 31 of those within Six Rivers CISMA.

Description:

This reddish colored grass can cover large areas of open fields. The reddish color comes from the hair-like structures that are associated with the flowers and will become gray with age. The flowers themselves are a pink-purple in color and are produced from panicles (a cluster of small flowers) that are 4-8 inches long. The grass can reach a height of 40 inches and dispersal is by wind blown seeds.

Issues and Impacts:

It aggressively grows in open fields and displaces native grass species from these areas. Many of which are important to local ecology.

Management:

Hand removal of small patches can be effective, but the property owner should be aware of the ease of seed dispersal when doing this, it is recommended to remove prior to going to seed. It tends to quickly invade open areas of disturbance including the use of fire. Mowing does not provide control.

The herbicides glyphosate and imazapyr have shown to have good control but must be used prior to going to seed. Both herbicides are non-selective, and care must be taken not to treat native plants. Imazapyr has a longer soil life and replanting the area after treatment may not be effective for several months.

There are no known biological controls at this time.

If you are in the Florida panhandle area and believe you may have natal grass, please contact your county extension office to let them know as well as report the siting to www.EDDMapS.org. If you have questions on how to do this, your county extension office can help.

For more information on this EDRR species, contact your local extension office.

References

University of Florida IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Natal Grass. https://plants.ifas.ufl.edu/plant-directory/melinis-repens/.

Early Detection and Distribution Mapping System (EDDMapS)

https://www.eddmaps.org/

Six Rivers CISMA

https://www.floridainvasives.org/sixrivers/