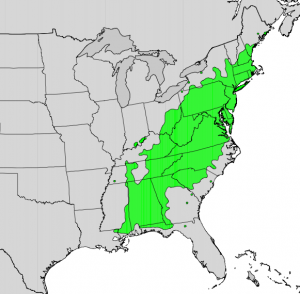

If you are lucky enough to live on the southern Alabama edge of northwest Florida, you may want to see if you can find mountain laurel blooming now near the wooded creeks. Its native range stretches from southern Maine south to northern Florida, just dipping into our area. The plant is naturally found on rocky slopes and mountainous forest areas. Both are nearly impossible to find in Florida. However, it thrives in acidic soil, preferring a soil pH of 4.5 to 5.5 and oak-healthy forests. That is something we do have. The challenge is to find a cool slope near spring-fed water.

Mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia) was first recorded in America in 1624, but it was named after Pehr Kalm, who had collected and submitted samples to Linnaeus in the 18th century. The wood of mountain laurel was popular for small household items. It is heavy and strong with a close, straight grain. However, as it grow larger it becomes brittle. Native Americans used the leaves as an analgesic. But, all parts of the plant are toxic to horses, goats, cattle, deer, monkeys and humans. In fact, food products made from it, including honey, can produce neurotoxic and gastrointestinal symptoms in people consuming more than a modest amount. Luckily, the honey is usually so bitter that most will avoid eating it.

One of the most unusual characteristics of mountain laurel is its unique method of dispersing pollen. As the flower grows, the filaments of its stamens are bent, creating tension. When an insect lands on the flower, the tension is released, catapulting the pollen forcefully onto the insect. Scientific experiments on the flower have demonstrated it ability to fling the pollen over 1/2 inch. I guess if you don’t taste that good, you have to find a way to force the bees to take pollen with them.

The mountain laurel in these pictures is from Poverty Creek, a small creek near our office in Crestview. This is their best bloom in 10 years. Maybe you can find some too.

- Watch for “Melting Grass” - February 19, 2025

- Palms Can Suffer in the Cold - January 30, 2025

- Camellia Care - January 9, 2025