by Ray Bodrey | Mar 20, 2025

Florida is synonymous with sand dunes and sea oats and evidence can be seen across the state’s vast shoreline landscape. Sand dunes are an important part of both the ecosystem and as a storm protection measure for coastal communities. Sea oats play an integral role in maintaining this healthy coastal ecosystem.

Sand dune in St. Joe Beach. Credit: Ray Bodrey UF/IFAS Extension

The raw power of ocean waves and seemingly constant weather conditions keep sand in motion on Florida’s beaches. Fortunately, there is a natural mechanism that holds sand in place to stabilize the shoreline. Sand dunes are simply formed though three basic principles: sand, wind and space. The process of dune formation occurs when the ocean pushes sand on shore, wind blows sand further onto the beach and sand gets trapped and accumulates. This creates a frontal and back dune area. Dunes are categorized by many factors, such as size, shape, biodiversity and vegetation. Back dune areas are home to a diverse host of plants and animals. Wildflowers, shrubs, grasses and even trees can be found in the network of hills in the back dune area. Shore birds such as the snowy plover and ruddy turnstone find solace in these areas. The endangered dune mice also live in the back dune areas, as a place of refuge and protection.

With vegetation as a cover, frontal dunes are anchored and tend to stay in place. Storm surges can easily erode dunes without vegetation. This can affect coastal communities in combatting storm surge and flooding. One of the most viable plants that secure dunes is sea oats (Uniola paniculata). This clumping grass is found on both beaches and dunes. The plant gets its common name from the seed head, which looks similar to field oats. Sea oats are extremely drought and salt tolerant. These plants need limited soil fertility to grow, making them the perfect plants for sand dunes. Sea oats also reproduce vegetatively through complex root system call rhizomes. The vast root system caused by rhizomes is a big reason why these plants are excellent at securing sand on dunes. The plant structure is very flexible, so the plant can endure strong coastal winds. Sea oats are native species that help provide habitat for coastal animals, as well.

Recently restored sand dune in St. Joe Beach. Credit: Ray Bodrey, UF/IFAS Extension

Sea oats are protected by law. It is illegal to collect sea oats for any reason in the wild without proper permitting. There are native plant nurseries that propagate sea oat seedlings for dune restoration. For more information on volunteer opportunities to assist in dune restoration, please contact your local county extension office.

Supporting information for this article can be found at the UF/IFAS EDIS Publication, “Sea Oats, Uniola paniculata”: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/SG186

by Beth Bolles | Mar 6, 2025

One plant that signals our change in season is beginning to bloom in natural areas and woodland gardens. The Red buckeye, Aesculus pavia, is forming large spikes of red flowers and the attractive palmate leaves are unfurling.

Red buckeye in the late winter sunshine. Photo by Beth Bolles UF IFAS Extension Escambia County.

If you enjoy a more natural landscape, Red buckeye is a perfect fit. It often has open growth with multiple branching stems which give it more of a shrub look in many landscapes. Plant size can vary from 8-15 feet. The blooms are beautiful and the tubular flowers can be visited by overwintering or returning hummingbirds.

Single bloom with palmate leaves. Photo by Beth Bolles UF IFAS Extension Escambia County

Although plants can tolerate full sun, plants look their best with some afternoon shade as the summer progresses. A high canopy that allows filtered sun would be excellent throughout our summer weather. Choose a location with moist, well drained soils. In general, plants will drop leaves earlier than other deciduous plants in your landscape so make sure your location is a spot to show off the late winter/early spring blooms.

A precaution with the Red buckeye is that the fruit is toxic for people and pets. The large capsules will contain several seeds which can drop and grow new plants. Squirrels will also enjoy the seeds.

by Carrie Stevenson | Dec 18, 2024

A large Carolina wolfberry shrub thrives near St. Marks’ lighthouse at the wildlife refuge. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

I was lucky enough to spend a weekend in November exploring a lovely, low-key stretch of northwest Florida. We hiked trails and took the boat tour at Wakulla Springs State Park, marveling at the numerous alligators and admiring birds and a slow-moving manatee. We also hiked through St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge, which is home to a nearly 200-year-old lighthouse and keeper’s house, which have a fascinating history of their own.

The brilliant red, and edible, berry of the Carolina wolfberry is ripe in late fall/early December. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Exploring the shoreline of Apalachee Bay behind the lighthouse, we watched fiddler crabs run the salt flats and herons quietly stalk their prey. Always on the lookout for something new, I noticed a large shrub growing several yards back from the beach. It looked like a cross between a rosemary and a holly, with delicate lavender/purple flowers and brilliant red teardrop-shaped fruit. I’d never seen it before.

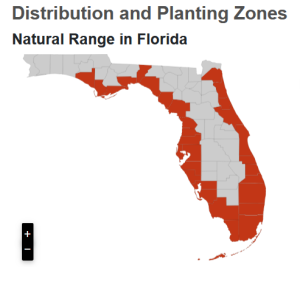

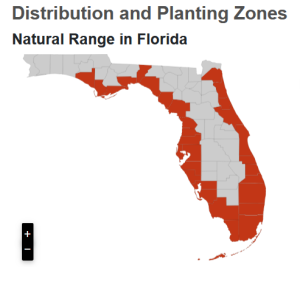

Map of the natural range of Carolina wolfberry in Florida. Figure courtesy of the Florida Native Plant Society.

After a quick investigation, I learned it was a Carolina wolfberry, aka Carolina deserthorn, aka Christmas berry (Lycium carolinianum). The invasive species coral ardisia (Ardisia crenata) is also known in some areas as Christmas berry—this is why scientific names are so useful—but that is not the plant we saw at St. Marks. The native Carolina wolfberry was located right where you might expect it, on dry coastal scrub, in view of the saltwater it easily tolerates. Its native range in Florida starts along the coastline east of here, particularly Bay and Wakulla counties and all the way down around the state.

The delicate lavender flower of the Carolina wolfberry is a popular nectar source for native butterflies. Photo credit: Peggy Romfh

The tall shrub is evergreen, with leaves adapted into a long, thin, slightly succulent near-needle shape. This leaf form helps hold water in a dry, salty environment and prevents evaporation. The tips of the shrub’s branches have thorns, hence the common name “desert-thorn.” Carolina wolfberry produces those attractive little purple blooms in the fall, providing nectar for several species of native butterflies. In late fall/early winter, the brilliant red fruits show up. They are less than an inch long and reminiscent of peppers. When ripe, the fruit are edible and are described as sweet and tomato-like. The fruit are not only popular for human consumption, but also for birds, deer, and raccoons. Just before we walked down the beach, another visitor saw a bobcat disappear into the shrub, which provides cover for many additional species besides those who eat it directly.

Illustration from a 15th century plant medicine book showing the mandrake, a member of the Solanaceae family.

Carolina wolfberry is a member of the Solanaceae family, aka nightshade (sometimes referred to as “deadly nightshade”). Other relatives include edible tomatoes, peppers, potatoes, eggplant, and groundcherry. The “deadly” part refers to related species like belladonna and mandrake, from which toxic poisons can be extracted. If you’re looking for a fascinating historical deep dive into these plants’ connection to witches, Shakespeare, and the death of multiple Roman emperors, look no further than the US Forest Service’s web page on the “Powerful Solanaceae” family!

by Danielle S. Williams | Dec 5, 2024

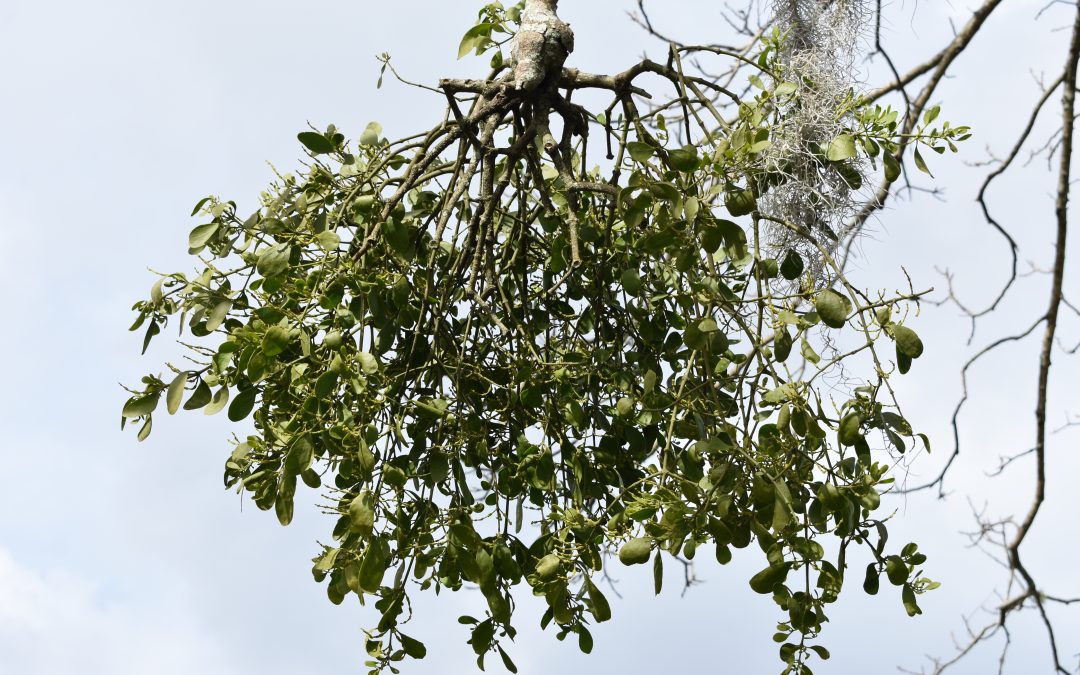

A kiss under the mistletoe…a timeless holiday tradition that we’ve all heard of. If you look around, you’ll be sure to find some growing on the branches of several different species of hardwood trees throughout the Panhandle. This same mistletoe is often harvested and brought inside to add a festive touch to holiday decorations.

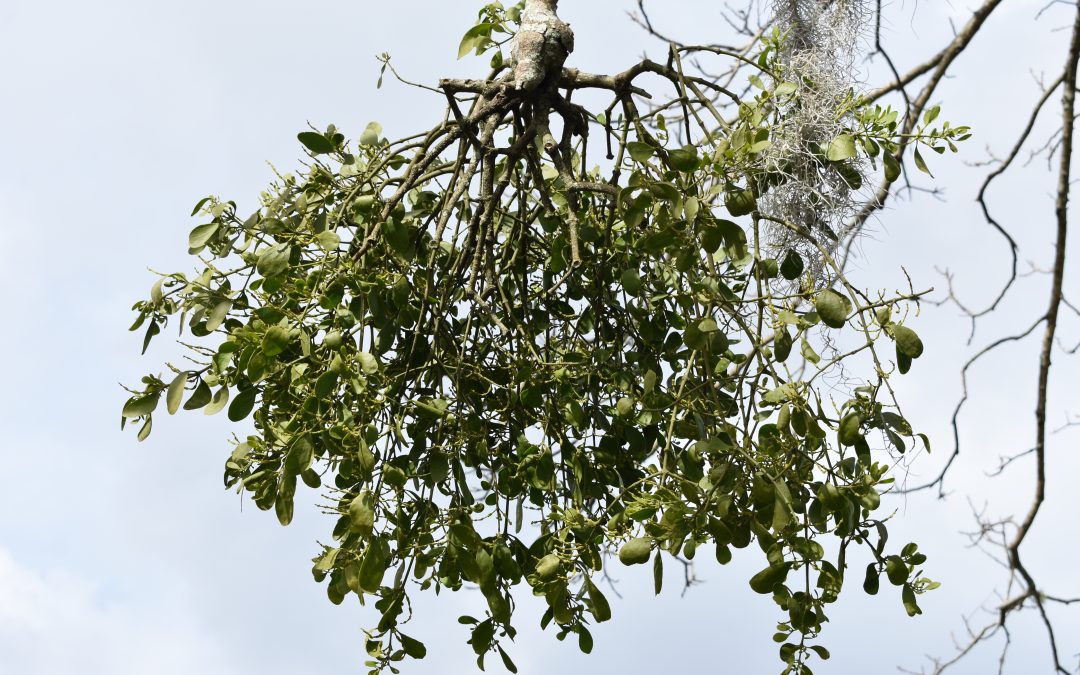

Mistletoe hanging in pecan tree. Photo credit: Danielle Williams.

The species we have here is known as American or oak mistletoe. It only grows in deciduous trees that shed their leaves annually. While mistletoe has over 200 host plants, you’ll find it most commonly in oaks, maples, and pecans. Look for a green, ball shaped mass about 3’ wide in the tops of trees. Each mass is an individual mistletoe plant, and some trees may have a few or many.

Mistletoe. UF/IFAS Photo by Tyler Jones.

Mistletoe is a small, evergreen shrub with white berries. It is considered a hemi-parasitic plant because it can produce some of its own food through photosynthesis, but it also relies on its host tree for water and nutrients. Most healthy trees can tolerate mistletoe without suffering any significant harm. However, trees that become severely infested with mistletoe can become weakened and decline in health, especially if the tree is already stressed by pests, drought or disease.

Pecan Tree Infested with Mistletoe. Photo credit: Danielle Williams.

If you have mistletoe growing on trees in your yard, the best way to support the trees is to maintain their overall health through proper watering, fertilization and pest management. If you suspect trees on your property are suffering from mistletoe, you can prune the infected branches. Since mistletoe roots from its host tree, simply cutting it flush with the branch will not kill it. You can remove the roots by pruning at least six inches below the point of attachment.

While some may consider mistletoe to be a nuisance, it does provide ecological benefits. Mistletoe serves as a valuable resource to our wildlife, primarily birds and insects. Oak mistletoe is the only food source for the larvae of the great purple hairstreak butterfly.

If you are considering harvesting mistletoe this winter to use for decoration, be sure to place it carefully. Mistletoe berries and all parts of the plant are poisonous to humans so keep plants and decorations out of the reach of children and pets. For more information on mistletoe, contact your local UF/IFAS Extension Office.

by Beth Bolles | Oct 17, 2024

UF IFAS Extension Escambia County was recently able to offer a native tree and shrub giveaway to our community. A county partner had some grant funding remaining and chose a nice selection of plants grown by a local native nursery. After seeing the plant selection, I was really excited that a few participating homeowners had the opportunity to take home one of my favorite native plants, the Sparkleberry, Vaccinium arboretum.

The Sparkleberry in the corner of my back yard. Photo by Beth Bolles, UF IFAS Extension Escambia County

Twenty-three years ago, I saved a sparkleberry on my new home lot because I loved this native tree. It has interest in all seasons in my opinion, including flowers, small fruit for wildlife, attractive bark, and an interesting shape as it matures. It has been a slower growing tree than others in my yard but I have enjoyed watching the tree develop its form and the bark develop the beautiful flaky cinnamon-brown look.

Sparkleberry bark and structure are attractive features in the landscape. Photo by Beth Bolles, UF IFAS Extension Escambia County.

The small tree is now about 12 feet tall and has never had any issues in the sandy, well drained soil. It can tolerate some moisture as long as the soil drains well. A grouping of trees from my neighbor’s lot keeps the plant in partial shade and we can often find sparkleberry specimens in the filtered light of woods. It can tolerate a sunnier location if that is the spot you have available for a small tree.

In addition to our enjoyment of this native tree, pollinators and other animals will appreciate the flower nectar, pollen, and berries. If you have a native nursery close to your home, be sure to ask for your own Sparkleberry if your site is suitable.

by Daniel J. Leonard | Sep 19, 2024

Problem areas in the landscape – everyone has them. Whether it’s the spot near a drain that stays wet or the back corner of a bed that sunshine never touches, these areas require specialized plants to avoid the constant frustration of installing unhealthy plants that slowly succumb and must be replaced. The problem area in my landscape was a long narrow bed, sited entirely under an eave with full sun exposure and framed by a concrete sidewalk and a south-facing wall. This bed stays hot, it stays dry, and is nigh as inhospitable to most plants as a desert. Enter a plant specialized to handle situations just like this – Yarrow ‘Moonshine’.

Yarrow (Achillea spp.) is a large genus of plants, occurring all over the globe. To illustrate, Common Yarrow (Achillea millefolium) is native to three different continents (North America, Europe, and Asia), making it one of the most widely distributed plants in the world. And though it was commonly grown and used in antiquity for medical purposes (the genus name Achillea is a reference to Achilles, who supposedly used the plant as a wound treatment for himself and his fellow Greek soldiers), I and most of you are probably more interested in how it looks and performs in the landscape.

‘Moonshine’ Yarrow foliage.

All species of Yarrow share several ornamental traits. The most obvious are their showy flowers, which occur as large, flattened “corymbs” and come in shades of white, pink, red, and yellow. I selected the cultivar ‘Moonshine’ for my landscape as it has brilliant yellow flowers that popped against the brown wall of the house. Equally as pretty and unique is the foliage of Yarrow. Yarrow leaves are finely dissected, appearing fernlike, are strongly scented, and range in color from deep green to silver. Again, I chose ‘Moonshine’ for its silvery foliage, a trait that makes it even more drought resistant than green leaved varieties.

‘Moonshine’ Yarrow inflorescence.

If sited in the right place, most Yarrow species are easy to grow; simply site them in full sun (6+ hours a day) and very well drained soil. While all plants, Yarrow included, need regular water during the establishment phase, supplemental irrigation is not necessary and often leads to the decline and rot of Yarrow clumps, particularly the silver foliaged varieties like ‘Moonrise’ (these should be treated more like succulents and watered only sparingly). Once established, Yarrow plants will eventually grow to 2-3’ in height but can spread underground via rhizomes to form clumps. This spreading trait enables Yarrow to perform admirably as a groundcover in confined spaces like my sidewalk-bound bed.

If you have a dry, sunny problem spot in your landscape and don’t know what to do, installing a cultivar of Yarrow, like ‘Moonshine’, might be just the solution to turn a problem into a garden solution. This drought tolerant, deer tolerant, pollinator friendly species couldn’t be easier to grow and will reward you with summer color for years to come. Plant one today. For more information on Yarrow or any other horticultural question, contact your local UF/IFAS County Extension Office.