by Mary Salinas | Aug 18, 2021

For those of you who tuned into the July 29 edition of Gardening in the Panhandle LIVE, beneficial insects was the topic of the day. Here are links to the publications our panelists talked about.

Mantid. Photo credit: David Cappaert, Bugwood.org.

How do I identify the kind of insect I have?

Recognizing beneficial bugs: Natural Enemies Gallery from UC Davis http://ipm.ucanr.edu/natural-enemies/

How to distinguish the predatory stink bug from the ones that harm our crops: https://entomology.ces.ncsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/FL-pred.jpg

How to tell difference in stink bugs and leaf footed insects. Are both harmful? UF/IFAS Featured Creatures: leaffooted bug – Leptoglossus phyllopus (Linnaeus) (ufl.edu)

How can I tell bad beetles from good ones? Helpful, Harmful, Harmless Identification Guide is one resource available: http://ifasbooks.ifas.ufl.edu/p-153-helpful-harmful-harmless.aspx

How can we encourage beneficial insects?

How can we encourage the beneficial insect species?

- Plant more flowers attract pollinators that also feed on insects.

- Diversity of plants in the landscape.

- Use softer or more selective pesticides to minimize damage to beneficials.

Is it helpful to order beneficial insects such as lady bugs? Encouraging Beneficial Insects in Your Garden OSU: https://catalog.extension.oregonstate.edu/sites/catalog/files/project/pdf/pnw550.pdf

How effective is buying predatory insects to release in your greenhouse? Natural Enemies and Biological Control: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/IN120

Can I buy beneficial insects to start breeding in my garden? Natural Enemy Releases for Biological Control of Crop Pests: https://www2.ipm.ucanr.edu/agriculture/natural-enemy-releases-for-biological-control-of-crop-pests/

What benefit would result by planting city right-of-ways with native wild flowers? https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/in1316; https://adamgdale.files.wordpress.com/2020/03/gcm_feb2020.pdf

Can an individual gardener sustain an ecosystem for beneficial insects? Penn State Article on beneficial insects that mentions some flowering plants that help support predators and parasitoids: https://extension.psu.edu/attracting-beneficial-insects

Specific Insects

How do I get rid of mole crickets? UF/IFAS Mole Crickets: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/entity/topic/mole_crickets

Are wasps really beneficial? Beneficial Insects: Predators!: https://sfyl.ifas.ufl.edu/sarasota/gardening-and-landscaping/horticulture-commercial/integrated-pest-management/beneficial-insects/

Is a dish soap solution effective against wasps? Soaps, Detergents, and Pest Management: https://gardeningsolutions.ifas.ufl.edu/care/pests-and-diseases/pests/management/soaps-detergents-and-pest-management.html

How to control leaf footed bugs? Handpick them, attract beneficials, create diverse plantings in landscape, accept some damage, and control them when in the juvenile stage.

Can you tell me about praying mantids? Praying Mantids: https://entomology.ca.uky.edu/files/efpdf2/ef418.pdf

Are there any beneficial insects that keep mosquito populations down? Dragonfly larvae in water, mosquitofish

What are the little insects that hop out of centipede grass? Are they beneficial?

Spittlebugs and your lawn: https://nwdistrict.ifas.ufl.edu/hort/2020/05/27/spittlebugs-and-your-lawn/

How to stop Eastern Black Swallowtail Butterflies laying eggs on parsley – the hatched caterpillars eat it all. Plant extra or put a screen over plant.

Extra fun video!

Take a look at this video of parasitic wasp attacking aphids: Parasitic Wasps | National Geographic – YouTube

by Sheila Dunning | Jun 10, 2021

Are you one of those that hear the word “pollen” and sneeze? For many, allergies are the only association with plant pollen. But pollination – the transfer of male pollen grains into the female flower organs to create fertile seeds – is an essential part of a healthy ecosystem. Pollinators play a significant role in the production of over 150 food crops. Corn and rice are wind pollinated. Just about everything else, including chocolate, depends on an insect, bird or mammal. Successful pollination of a single flower often requires visits from multiple pollinators. But, there are also plants that need a specific species in order to complete the task. They are so interdependent that if one disappears, so will the other.

Unfortunately, reports from the National Research Council say that the long-term population trends for some North American pollinators are “demonstrably downward”.

In 2007, the U.S. Senate unanimously approved and designated “National Pollinator Week” to help raise awareness. National Pollinator Week (June 21-27, 2021) is a time to celebrate pollinators and spread the word about what you can do to protect them. Habitat loss for pollinators due to human activity poses an immediate and frequently irreversible threat. Other factors responsible for population decreases include: invasive plant species, broad-spectrum pesticide use, disease, and weather.

In 2007, the U.S. Senate unanimously approved and designated “National Pollinator Week” to help raise awareness. National Pollinator Week (June 21-27, 2021) is a time to celebrate pollinators and spread the word about what you can do to protect them. Habitat loss for pollinators due to human activity poses an immediate and frequently irreversible threat. Other factors responsible for population decreases include: invasive plant species, broad-spectrum pesticide use, disease, and weather.

So what can you do?

- Install “houses” for birds, bats, and bees.

- Avoid toxic, synthetic pesticides and only apply bio-rational products when pollinators aren’t active.

- Provide and maintain small shallow containers of water for wildlife.

- Create a pollinator-friendly garden.

- Plant native plants that provide nectar for pollinating insects.

There’s a new app for the last two.

The Bee Smart® Pollinator Gardener is your comprehensive guide to selecting plants for pollinators based on the geographical and ecological attributes of your location (your ecoregion) just by entering your zip code. http://pollinator.beefriendlyfarmer.org/beesmartapp.htm

Filter your plants by what pollinators you want to attract, light and soil requirements, bloom color, and plant type. This is an excellent plant reference to attract bees, butterflies, hummingbirds, beetles, bats, and other pollinators to the garden, farm, school and every landscape.

The University of Florida also provides a website to learn the bee species and garden design. Go to: https://ffl.ifas.ufl.edu/bees/Bee

or go on-line to see a list of pollinator-attracting plants. https://gardeningsolutions.ifas.ufl.edu/design/gardening-with-wildlife/bee-plants.html

Not only can you find out which plants attract pollinators, you will be given the correct growing conditions so you can choose ‘the right plant for the right place’.

Remember, one out of every three mouthfuls of food we eat is made possible by pollinators.

by Molly Jameson | Oct 28, 2020

The Carolina wolf spider (Hogna Corolinensis) is the largest wolf spider, measuring up to 22-35 mm. It is the state spider of South Carolina, the only state that recognizes a spider as a state symbol. Photo by Eugene E. Nelson, Bugwood.org.

Halloween coincides with a full moon this year, so you may want to be on the lookout for hungry werewolves. In your garden, you may also be on the lookout for a much smaller, yet just as frightful, type of wolf. Well – wolf spider, that is!

But have no fear, just as the little werewolves of the neighborhood will be sated by a handful of sweets, a wolf spider will be satisfied once it finds its meal of choice. Wolf spiders are predators, feeding primarily on insects and other spiders. Much like a werewolf, wolf spiders prefer to stalk their prey at night. This is good news for gardeners – as it means you’ll have an insect hunter working for you while you sleep.

Wolf spiders are in the family Lycosidae, and there are over 2,000 species within this family. Lycos means “wolf” in Greek, inspired by the way wolves stalk their prey. Although, unlike wolves who hunt in packs, wolf spiders are very much solitary. These spiders do not spin webs; instead, they keep to the ground, where they can blend in with leaf litter on the soil floor. Some wolf spiders even dig tunnels, or use tunnels dug by other animals, to hide and hunt.

Although most spiders have poor eyesight, wolf spiders have excellent vision, which they use to spot prey. Photo by James O. Howell, University of Georgia, Bugwood.org.

Wolf spiders have eight eyes that are arranged in three rows. This includes four small eyes in the lowest row, two very large eyes in the middle, and two medium-sized eyes off to either side on top. Some of their eyes even have reflective lenses that seem to sparkle in the moonlight. Using their excellent eyesight and sensitivity to vibrations, they stealthily stalk prey such as ants, grasshoppers, crickets, and other spider species. Female wolf spiders, which are bigger than males, may even take down the occasional lizard or frog.

No matter the meal, many wolf spiders pounce on their prey, hold it between their eight legs, and roll with it onto their backs, creating a trap. They then sink their powerful fangs, which are normally retracted inside the jaw, into the victim. The fangs have a small hole and hollow duct, which allows venom from a specialized gland to pass through during the bite. This venom quickly kills the prey, allowing the wolf spider to eat in peace.

Although wolf spiders could bite a person if threatened, they prefer to run away, and their venom is not very toxic to humans. If you do get bitten, you may have some swelling and redness, but no life-threatening symptoms have been reported. Werewolves on the other hand? For these, you’re on your own!

by Daniel J. Leonard | Oct 14, 2020

Article by Jessica Griesheimer & Dr. Xavier Martini, UF/IFAS North Florida Research and Education Center, Quincy

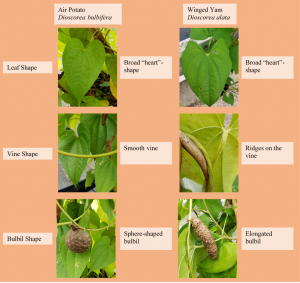

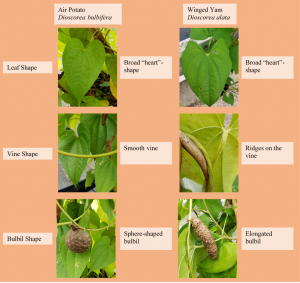

Dioscorea bulbifera, commonly known as the air potato is an invasive species plaguing the southeastern United States. The air potato is a vine plant that grows upward by clinging to other native plants and trees. It propagates with underground tubers and aerial bulbils which fall to the ground and grow a new plant. The aerial bulbils can be spread by moving the plant, causing the bulbils to drop to the ground and tubers can be spread by moving soil where an air potato plant grew prior. The air potato is commonly confused with and mistaken as being Dioscorea alata, the winged yam which is also highly invasive. The plants look very similar at first glance but have subtle differences. Both plants exhibit a “heart”-shaped leaf connected to vines. The vines of the winged yam have easily felt ridges, while the air potato vines are smooth. They also differ in their aerial bulbil shapes, the winged yam has a long, cylinder-shaped bulbil while the air potato aerial bulbil has a rounded, “potato” shape (Fig. 1).

In its native range of Asia and Africa, the air potato has a local biocontrol agent, Lilioceris cheni commonly known as the Chinese air potato beetle (Fig. 2). As an adult, this beetle feeds on older leaves and deposits eggs on younger leaves for the larvae to later feed on. Once the larvae have grown and fed, they drop the ground where they pupate to later emerge as adults, continuing the cycle. The Chinese air potato beetle will not feed on the winged yam, as it is not its host plant.Current methods of air potato plant, bulbil, and tuber removal can be expensive and hard to maintain. The plant is typically sprayed with herbicide or is pulled from the ground, the aerial bulbils are picked from the plant before they drop, and the underground tubers are dug up. The herbicides can disrupt native vegetation, allowing for the air potato to spread further should it survive. If the underground tuber or aerial bulbils are not completely removed, the plant will grow back.

The Chinese air potato beetle is currently being evaluated as a potential integrated pest management (IPM) organism to help mitigate the invasive air potato. The beetle feeds and reproduces solely on the air potato plant, making it a great IPM organism choice. During 2019, we studied the Chinese air potato beetle and its ability to find the air potato plant. It was found the beetles may be using olfactory cues to find the host plant. Further research is conducted at the NFREC to increase natural aggregation of the beetles on air potato to improve biological control of the weed.

Chinese Air Potato Leaf Beetle.

If you have the air potato plant, or suspect you have the air potato plant, contact your local UF/IFAS Extension Agents for help!

by Daniel J. Leonard | Sep 28, 2020

2020 has not been the most pleasant year in many ways. However, one positive experience I’ve had in my raised bed vegetable garden has been the use of a cover crop, Buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum)! Use of cover crops, a catch-all term for many species of plants used to “cover” field soil during fallow periods, became popular in agriculture over the last century as a method to protect and build soil in response to the massive wind erosion and cropland degradation event of the 1930s, the Dust Bowl. While wind erosion isn’t a big issue in raised bed gardens, cover crops, like Buckwheat, offer many other services to gardeners:

Buckwheat in flower behind summer squash. Photo courtesy of Daniel Leonard.

- Covers, like Buckwheat, provide valuable weed control by shading out the competition. Even after termination (the cutting down or otherwise killing of the cover crop plants and letting them decompose back into the soil as a mulch), Buckwheat continues to keep weeds away, like pinestraw in your landscape.

- Cover crops also build soil. This summer, I noticed that my raised beds didn’t “sink” as much as normal. In fact, I actually gained a little nutrient-rich organic matter! By having the Buckwheat shade the soil and then compost back into it, I mostly avoided the phenomena that causes soils high in organic matter, particularly ones exposed to the sun, to disappear over time due to breakdown by microorganisms.

- Many cover crops are awesome attractors of pollinators and beneficial insects. At any given time while my Buckwheat cover was flowering, I could spot several wasp species, various bees, flies, moths, true bugs, and even a butterfly or two hovering around the tiny white flowers sipping nectar.

- Covers are a lot prettier than bare soil and weeds! Where I would normally just have either exposed black compost or a healthy weed population to gaze upon, Buckwheat provided a quick bright green color blast that then became covered with non-stop white flowers. I’ll take that over bare soil any day.

Buckwheat cover before termination (left) and after (right) interplanted with Eggplant. Photo courtesy Daniel Leonard, UF/IFAS Calhoun County Extension.

Now that I’ve convinced you of Buckwheat’s raised bed cover crop merits, let’s talk technical and learn how and when to grow it. Buckwheat seed is easily found and can be bought in nearly any quantity. I bought a one-pound bag online from Johnny’s Selected Seeds for my raised beds, but you can also purchase larger sizes up to 50 lb bags if you have a large area to cover. Buckwheat seed germinates quickly as soon as nights are warmer than 50 degrees F and can be cropped continuously until frost strikes in the fall. A general seeding rate of 2 or 3 lbs/1000 square feet (enough to cover about thirty 4’x8’ raised beds, it goes a long way!) will generate a thick cover. Simply extrapolate this out to 50-80 lbs/acre for larger garden sites. I scattered seeds over the top of my beds at the above rate and covered lightly with garden soil and obtained good results. Unlike other cover crops (I’m looking at you Crimson Clover) Buckwheat is very tolerant of imperfect planting depths. If you plant a little deep, it will generally still come up. A bonus, no additional fertilizer is required to grow a Buckwheat cover in the garden, the leftover nutrients from the previous vegetable crop will normally be sufficient!

Buckwheat “mulch” after termination. Photo courtesy of Daniel Leonard, UF/IFAS Calhoun County Extension.

Past the usual cover crop benefits, the thing that makes Buckwheat stand out among its peers as a garden cover is its extremely rapid growth and short life span. From seed sowing to termination, a Buckwheat cover is only in the garden for 4-8 weeks, depending on what you want to use it for. After four weeks, you’ll have a quick, thick cover and subsequent mulch once terminated. After eight weeks or so, you’ll realize the plant’s full flowering and beneficial/pollinator insect attracting potential. This lends great flexibility as to when it can be planted. Have your winter greens quit on you but you’re not quite ready to set out tomatoes? Plant a quick Buckwheat cover! Yellow squash wilting in the heat of summer but it’s not quite time yet for the fall garden? Plant a Buckwheat cover and tend it the rest of the summer! Followed spacing guidelines and only planted three Eggplant transplants in a 4’x8’ raised bed and have lots of open space for weeds to grow until the Eggplant fills in? Plant a Buckwheat cover and terminate before it begins to compete with the Eggplant!

If a soil building, weed suppressing, beneficial insect attracting, gorgeous cover crop for those fallow garden spots sounds like something you might like, plant a little Buckwheat! For more information on Buckwheat, cover crops, or any other gardening topic, contact your local UF/IFAS County Extension Office. Happy Gardening!

by Mary Salinas | Sep 8, 2020

Perennial milkweed, Asclepias perennis, with oleander aphids; notice the brown aphid mummies that have been parasitized. Photo credit: Mary Salinas UF/IFAS Extension.

Milkweeds are appreciated for their beauty, but often we cultivate it for the benefit of the monarch butterflies who lay their eggs only on this plant genus. Avid butterfly gardeners want the monarch caterpillars to eat up the milkweed and become beautiful butterflies. Often instead, thousands of aphids show up and compete for space on the plants. These bright yellow aphids are known as oleander aphids.

Just how do aphids build up their populations so quickly? It seems that one day you have a small number on a few plants and then a few days later, thousands are all over your milkweed. Oleander aphids have a few advantages for quickly building their populations:

- All oleander aphids are female and do not need to mate to produce their young

- Aphids give birth to live young who immediately start feeding on the plant

- Aphids start reproducing when they are 4 to 10 days old and keep reproducing during their one-month life span

- When populations get heavy or the plant starts to decline, winged individuals are produced to migrate to new areas and plants.

Parasitic wasp and aphid mummies. Photo credit: University of California.

What can or should you do to control this pest?

One option is to do nothing and let the natural enemies come in and do their job. One of the best is a very tiny wasp that you will likely never see. This parasitoid lays its eggs only inside aphids. The wasp larva feeds on the inside of the aphid and turns it into a round brown ‘mummy’ and then emerges when mature by making a round hole in the top of the aphid. Look closely with a hand lens at some of those brown aphids on your milkweed and you can see this amazing process. Another common predator I see in my own garden is the larvae of the hover fly or syrphid fly. You will have to look hard to see it, but it is usually there. Assassin bugs and lady beetles also commonly feed on aphids. The larvae of lady beetles look nothing like the adults but also are voracious predators of aphids – check out what they look like.

Lady beetle larva feeding on aphid on tobacco. Photo credit:

Lenny Wells University of Georgia Bugwood.org.

If you think your situation requires some sort of intervention to control the aphids, first check carefully for monarch eggs and caterpillars, keeping in mind that some may be very small. Remove them, shoo away any beneficial insects, and spray the plant completely with an insecticidal soap product. Recipes that call for dish detergents may harm the waxy coating on the leaves and should be avoided. The solution must contact the insect to kill it. Always follow the label instructions. Soap will also kill the natural enemies if they are contacted. One exception is the developing wasp in the aphid mummies – fortunately, they are protected inside as the soap does not penetrate. Oils derived from plants or petroleum can serve the same purpose as the insecticidal soap.

Syrphid fly larva and oleander aphids. Photo credit: Lyle Buss, University of Florida.

You also can squish the aphids with your fingers and then rinse them off the plant. If you only rinse them off, the little pests can often just crawl back onto the plant.

There are systemic insecticides, like neonicotinoids, that are taken up by plant roots and kill aphids when they start feeding on the plants. However, those products also kill monarch caterpillars munching on the plant and harm adult butterflies, bees, and other pollinators feeding on the nectar. So those products are not an option. Always read the product label as many pesticides are prohibited by law from being applied to blooming plants as pollinators can be harmed.

In the end, consider tolerating some aphids and avoid insecticide use in landscape.

Happy butterfly gardening!