by Stephen Greer | Aug 11, 2021

One big goal of establishing a home lawn and landscape is to enjoy an attractive setting for family and friends, while also helping manage healthy soils and plants. Soil compaction at these sites can cause multiple problems for quality plants establishment and growth. Soil is an incredibly important resource creating the foundation for plants and water absorption.

Photo courtesy: Stephen Greer, UF IFAS

Soils are composed of many different things, including minerals. In Florida, these minerals often include sand of differing sizes and clay in the northern area of the counties in the panhandle of Florida. Soil is also composed of organic matter, nutrients, microorganisms and others. When soil compacts, the air spaces between the sand or clay are compressed, reducing the space between the mineral particles. This can occur anytime during the landscape and lawn construction phase or during long term maintenance of the area with equipment that could include tractors, mowers, and trucks.

What can be done to reduce soil compaction? There are steps that can be taken to help reduce this serious situation. Make a plan on how to best approach a given land area with the equipment needed to accomplish the landscape of your dreams. Where should heavy equipment travel and how much impact they will have to the soils, trees, and other plants already existing and others to be planted? At times heavy plywood may be needed to distribute the tire weight load over a larger area, reducing soil compaction by a tire directly on the soil. Once the big equipment use is complete, look at ways to reduce the areas that were compacted. Incorporating organic matter such as compost, pine bark, mulch, and others by tilling the soil and mixing it with the existing soil can help. Anytime the soil provides improved air space, root will better grow and penetrate larger areas of the soil and plants will be healthier.

Even light foot traffic over the same area over and over will slowly compact soils. Take a look at golf course at the end of cart paths or during a tournament with people walking over the same areas. The grass is damaged from the leaves at the surface to the roots below. Plugging these areas or possibly tilling and reestablishing these sites to reduce the compacted soils may be necessary.

Photo courtesy: Stephen Greer, UF IFAS

Water absorption is another area to plan for, as heavy rains do occur in Florida. Having landscapes and lawns that are properly managed allow increased water infiltration into the soil is critically important. Water runoff from the site is reduced or at least slowed to allow the nutrient from fertilizers used for the plant to have more time to be absorbed into the soil and taken up by the plants. This reduces the opportunity for nitrogen, phosphorus, and other nutrients to enter water areas such as ponds, creeks, lagoons, rivers and bays. Even if you are miles from an open water source, movement of water runoff can enter ditches and work their way to these open water areas, ultimately impacting drinking water, wildlife, and unwanted aquatic plant growth.

Plan ahead and talk with experts that can help with developing a plan. Contact your local Extension office for assistance!

by Daniel J. Leonard | Aug 5, 2021

The number one request all would-be gardeners and budding landscape enthusiasts have is “I want something that I don’t have to take care of, tolerates the heat, blooms, and comes back every year”. That is a tall order in our climate but not an impossible one, especially if one is willing to take a step back in time and consider an old Southern passalong plant, Garden Phlox (Phlox paniculata)!

Garden Phlox (Phlox paniculata) in a Calhoun County landscape. Photo courtesy of Daniel Leonard.

This old heirloom perennial is an outstanding ornamental for Panhandle landscapes. Every spring, Garden Phlox emerges from a long winter sleep and shoots its attractive bright green foliage straight up, reaching 3-5’ in height. After hiding inconspicuously in the landscape all spring, Phlox then blasts into fiery magenta bloom during the heat of summer, beginning the show in late June. While individual Phlox flowers are only 1” wide or so, they are held prominently above the plant’s foliage in large clusters up to 8” in diameter and are about as eye-catching as flowers come. The flower show continues through July and August until finally fading out as fall rolls around. Plants then set seed and ready themselves for winter dormancy, repeating the cycle the following spring. A bonus, though individual Phlox plantings start off as small, solitary clumps, they slowly expand over the years, never over-aggressively or unwanted, into a mass of color that becomes the focal point of any landscape they occupy!

In addition to being gorgeous, Phlox is adaptable and demands very little from gardeners. The species prefers to be sited in full, blazing sun but can also handle partial shade. Just remember, the more shade Phlox is in, the fewer flowers it will produce. Site accordingly. Phlox is also extremely drought tolerant, thriving in most any semi-fertile well-drained soil. Though it can handle drought like a champ, Phlox will languish if planted in a frequently damp location. If water stands on the planting site for more than an hour or so after a big rain event, it is most likely too wet for Phlox to thrive. Once established, Phlox is not a heavy feeder either. A light application of a general-purpose fertilizer after spring emergence from winter dormancy will sustain the plants’ growth and flowering all summer long!

Clump of Garden Phlox in a Calhoun County landscape. Photo courtesy of Daniel Leonard.

Though the ornamental and low-maintenance attributes of plain Garden Phlox make it sound like a perfect landscape plant, it is uncommon in the modern nursery trade, having fallen out of favor as many old plants often do. The species is still a familiar site around old home places, cemeteries, abandoned buildings, and the like throughout the South, but is difficult to find in most commercial nurseries. The primary reason for this is that the commercially available modern Phlox hybrids sporting exotic flower colors and shapes are not tolerant of our growing conditions. These new Garden Phlox hybrids were bred to perform in the milder conditions of more norther climes and are extremely susceptible to the many fungal diseases brought on by Florida’s heat and humidity of summer, particularly Powdery Mildew. It’s best to avoid these newcomers and stick to the old variety with its pink flowers and ironclad constitution. Plain old Garden Phlox can be found in some independent and native plant nurseries, but the best and most rewarding method of acquisition is to make friends with someone that already has a clump and dig up a piece of theirs!

If you have been looking for a low-maintenance, high impact perennial to add to your landscape, old-fashioned Garden Phlox might be just the plant for you! For more information on Garden Phlox, other landscape perennials, passalong plants or any other horticultural topic, contact your local UF/IFAS County Extension Office. Happy Gardening!

by Ray Bodrey | Jul 29, 2021

Need tips on planting and caring for trees? The primary focus in care of your newly planted tree is root development. It takes several months for roots to establish and newly planted trees and shrubs do not have a very strong root system. Start by digging the hole in a popcorn bowl shape. Once planted, backfill around the root system, but be careful not to compact the soil as this will hinder root growth. Be sure to keep the topmost area of the root ball exposed, about one to two inches. A layer of mulch will be applied here.

Frequent watering is much needed, especially if you are planting in the summer. Water thoroughly, so that water percolates below the root system. Shallow watering promotes surface root growth, which will make the plant more susceptible to stress during a drought. Concentrate some of the water in a diameter pattern a few feet from the trunk. This will cause the root system to grow towards the water, and thus better establish the root system and anchor the tree.

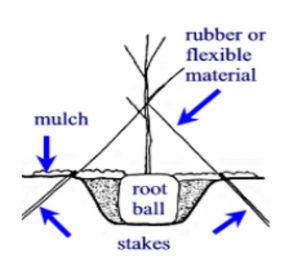

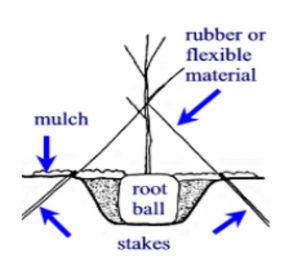

Figure: A Traditional Staking Option. Credit: Edward F. Gilman, UF/IFAS Extension.

Mulch is important in the conservation of soil moisture. Pine needles, bark, wood chips, and other organic materials make a great mulch. A three inch layer of mulch will usually suffice. It’s important to keep the mulch a few inches from the trunk as mulching too close to the tree trunk can cause rot.

You should always prune the bare roots of trees during planting. These exposed roots in containers can be damaged in shipping and removing some of the roots will help trigger growth. Pruning some of the top foliage can also reduce the amount of water needed for the plant to establish, as well. Trees and shrubs grown and shipped in burlap or containers usually need very little pruning.

Newly planted trees often have a difficult time establishing if the root system cannot be held in place. Strong winds and rain can cause the plant to tip over. Avoid this by staking the plant for temporary support. A good rule of thumb to determine staking need is if the trunk diameter measures three inches or less, it probably needs some support! Tie the stake to the plant every six inches from the top. However, only tie the trunk at one spot. Don’t tie too tightly so that the tree has no flexibility. This will stunt the growth of the tree.

Following these tips will help ensure your tree becomes well established in your landscape. For more information please contact your local county extension office.

Information for this article can be found in the UF/IFAS EDIS publication: “Planting and Establishing Trees” by Edward F. Gilman and Laura Sadowiski: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdf%5CEP%5CEP31400.pdf

Supporting information also provided by UF/IFAS Extension Forestry Specialist Dr. Patrick Minogue, of the North Florida Research Education Center in Quincy, Florida.

by Larry Williams | Jul 15, 2021

Q. One of my two fig trees has produced a few figs. The other one, which is the largest and healthiest tree, has never had a fig on it. Both where planted six years ago. Why is it not producing?

Mature fig tree with fruit. Photo credit: Larry Williams

A. It may be a matter of age and being overly vigorous. When a fruit tree is younger, it puts most of its energy into producing leaves and shoots. Until the plant becomes mature and slows down in the production of leaves and shoots, it will produce few to no fruit. It may take a year or two more for your tree to slowly and gradually switch from producing mostly leaves and shoots to producing and maturing some fruit. Patience is needed.

Be careful to not overdo it in fertilizing and/or pruning your fig tree. Too much fertilizer, especially nitrogen, or severely pruning the tree will result in the tree becoming overly vigorous at the expense of setting and maturing fruit. This includes fertilizer that the tree may pull up from a nearby lawn area. A tree’s roots will grow outward two to three times beyond its branch spread into adjacent lawn areas.

The end result of being heavy handed with fertilizing and/or overdoing it in pruning is the same – it forces the plant to become overly vigorous in producing leaves and shoots at the expense of producing and maturing fruit.

In addition, the following is taken from an Extension publication on figs and includes the most common reasons for lack of fruiting, in order of importance.

- Young, vigorous plants and over-fertilized plants will often produce fruit that drops off before maturing. If plants are excessively vigorous, stop fertilizing them. Quite often, three of four years may pass before the plant matures a crop because figs have a long juvenile period before producing edible quality fruit.

- Dry, hot periods that occur before ripening can cause poor fruit quality. If this is the case, mulching and supplemental watering during dry spells will reduce the problem.

- The variety Celeste will often drop fruit prematurely in hot weather regardless of the quality of plant care. However, it is still a good variety to grow.

- An infestation of root-knot nematodes can intensify the problem when conditions are as described in item 2.

- You could have a fig tree that requires cross-pollination by a special wasp. This is a rare problem. If this is the case, then it will never set a good crop. The best way to resolve this is to replace the plant with a rooted shoot of a neighbor’s plant you know produces a good crop each year.

by Mary Salinas | Jul 15, 2021

Brown-eyed Susan makes a nice addition to a pollinator garden. This one is visited by a scoliid wasp, a parasitoid of soil-inhabiting scarab beetle larvae. Photo credit: Mary Salinas, UF/IFAS Extension.

Black-eyed Susan, Rudbeckia hirta, has been a very popular garden perennial for generations. Fewer gardeners have experience with, or even heard of its’ close relative, brown-eyed Susan, Rudbeckia triloba. So, what is the difference between them?

- Brown-eyed Susan has more numerous flowers and generally flowers for a longer period in spring, summer, and fall.

- Black-eyed Susan has bigger flowers and bigger leaves.

- Both species are perennial, but the brown-eyed Susan tends to die out sooner after a few years. The good news is that both readily spread through seed to replace older plants.

Brown-eyed Susan. Photo credit: Mary Salinas, UF/IFAS Extension.

Brown-eyed Susan is native to the eastern and central United States and, although native to Florida, it has only been vouchered in the wild in 5 counties in Florida. Gardeners can find seed and plants readily online and at a few native plant nurseries. It is best to try to source wildflower seed from plants grown in the same region. Brown-eyed Susan seed from plants grown in Nebraska or Michigan may not be as well adapted to the Florida environment as locally grown seed.

If you want to add this pollinator attracting perennial to your garden, choose a spot that is sunny or partly sunny. Although it prefers moist soil, brown eyed Susan adapts to most soil types and is drought tolerant after establishment.

by Stephen Greer | Jul 1, 2021

Photo Courtesy: Stephen Greer

Lawn areas come in all sizes and shapes. Some are large open expanses providing long views and others are smaller versions surrounded by shrubs and trees creating a more private and secluded setting. There are a number of reasons for reducing the size of a lawn with some coming into play with your decisions. A home lawn is often an important part of the landscape that provides a place to play outdoors from picnicking, tossing the ball to taking a quite stroll.

Maintaining a healthy lawn is important to an overall performance of this part of the landscape. Several factors are involved in the success in keeping a strong and resilient lawn. Understanding the needs of a grass to remain healthy involve soil testing to address soil pH and nutrient needs plus water challenges. Misuse of fertilizer and over irrigation can be costly to you and to the overall health of the lawn. These decisions can lead to reducing lawn size to managing cost or removing underused areas.

There are big benefits to reducing your lawn from saving time in mowing, trimming and other manicuring needs to saving energy costs involving the lawn mower not to mention reducing pollution from the mower or weed eater. The reduced amounts of pesticides needed to manage weeds and disease to the lawn saves time and money.

Another way to look at the reducing the size of our lawn is there will be more space for expanding plant beds and potential tree placement. These settings increase the opportunities for a more biodiverse landscape providing shelter, protection and food options for birds and other wildlife.

Photo Courtesy: Stephen Greer

The lawn can serve as a transition space that leads from one garden room space to another, while still offering a location to bring the lawn chair out to enjoy all that is around your lawn. Lawns and the landscape are ever changing spaces, especially as your trees and shrubs grow and mature to sizes that can directly impact the lawn performance. Often levels of shade will diminish edges and other areas of the lawn. This often will define the reduction of the lawn size moving going forward. Just remember that lawns and landscapes occupy a three-dimensional space involving the horizontal, vertical and overhead spaces. Just look around and think about what is best for you, your family and the setting.Are you more interested in developing other parts of the landscape? With many of us spending more time at home over the last year plus it gave time to think about the outdoor areas. Growing our own vegetables may be a new or expanding part of the landscape with the use of raised beds or interplanting into the existing landscape. Gardening can assist in reducing stress while at the same time providing that fresh tomato, lettuce, herbs and other fun healthy produce.

What ever your decisions are enjoy the lawn and landscape. For additional information, contact your local University of Florida IFAS Extension office located in your county.