by Ray Bodrey | Apr 8, 2020

Spring has arrived and so have the insects. Caterpillars are crawling around and one possesses a unique appetite.

Neodiprion spp. is the most common defoliating insect group affecting pine trees. In all, there are 35 species that are native to the U.S. and Canada. The redheaded pine sawfly, Neodiprion lecontei, is the primary species found in the Florida Panhandle.

Adult sawflies can be as large as 1/3 of an inch in length. The female can be two-thirds larger than the male and are mostly black with a reddish-brown head, with occasional white coloration on the sides of the abdomen.

Mature larvae of the redheaded pine sawfly. Credit: Patty Dunlap, Gulf County Master Gardener.

The ovipositor, the tube-like organ used for laying eggs, is saw-like, hence the common name. During the fall, females make slits in pine needles and deposit individual eggs, up to 120 eggs at a time. The eggs are shiny, translucent and white-hued. Mature larvae (caterpillars), as seen in the accompanying photo, are yellow-green, emerge in the spring and feast on pine needles. After weeks of feeding on needles, the mature larvae drop to the ground. The cocoon, a reddish-brown, thin walled cylinder, is spun in the upper layer of the soil horizon or in the leaf litter; this is called the pupae stage. The pupae overwinter, and adults emerge from the cocoon in the spring of the following year.

Mature larvae are attracted to young, open growing pine stands. Pine is the preferred host, but cedar and fir, where native, are secondary food sources. Neodiprion lecontei is an important defoliator of commercially grown pine, as the preferred feeding conditions for sawfly larvae are enhanced in monocultures of shortleaf, loblolly, and slash pine, all of which are commonly cultivated in the southern United States. Defoliation can kill or slow the growth of pine trees as well as predispose trees to other insects or disease.

Are there control methods? Yes, biological control is a major factor, as natural enemies are numerous. Disease, viruses and predators help regulate population control. For small scale control, physically removing eggs or larvae is key. Again, most infestations occur on younger tree plantings, so they’ll be in reach. Be sure to scout young pines for signs of infestation. Horticultural soaps and oils are effective chemical controls, if needed.

For more information, contact your local county extension office.

Supporting information for this article can be found in the UF/IFAS Extension EDIS publication, “Redheaded Pine Sawfly Neodiprion lecontei” by Sara DeBerry: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/IN/IN88200.pdf

UF/IFAS Extension is an Equal Opportunity Institution.

by Matt Lollar | Oct 8, 2019

Last week at the Panhandle Fruit and Vegetable Conference, Dr. Ali Sarkhosh presented on growing pomegranate in Florida. The pomegranate (Punica granatum) is native to central Asia. The fruit made its way to North America in the 16th century. Given their origin, it makes sense that fruit quality is best in regions with cool winters and hot, dry summers (Mediterranean climate). In the United States, the majority of pomegranates are grown in California. However, the University of Florida, with the help of Dr. Sarkhosh, is conducting research trials to find out which varieties do best in our state.

In the wild, pomegranate plants are dense, bushy shrubs growing between 6-12 feet tall with thorny branches. In the garden, they can be trained as small single trunk trees from 12-20 feet tall or as slightly shorter multi-trunk (3 to 5 trunks) trees. Pomegranate plants have beautiful flowers and can be utilized as ornamentals that also bear fruit. In fact, there are a number of varieties on the market for their aesthetics alone. Pomegranate leaves are glossy, dark green, and small. Blooms range from orange to red (about 2 inches in diameter) with crinkled petals and lots of stamens. The fruit can be yellow, deep red, or any color in between depending on variety. The fruit are round with a diameter from 2 to 5 inches.

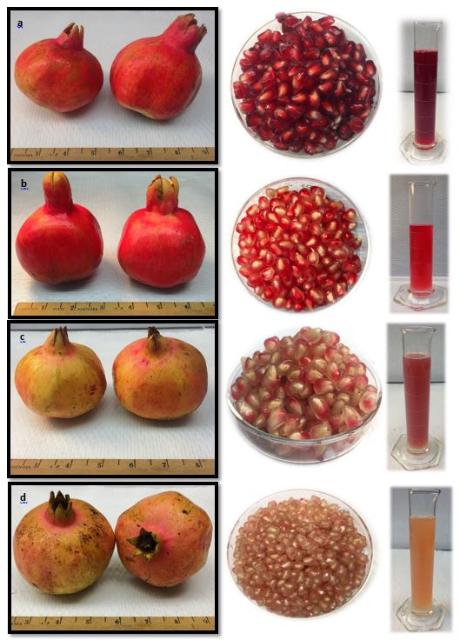

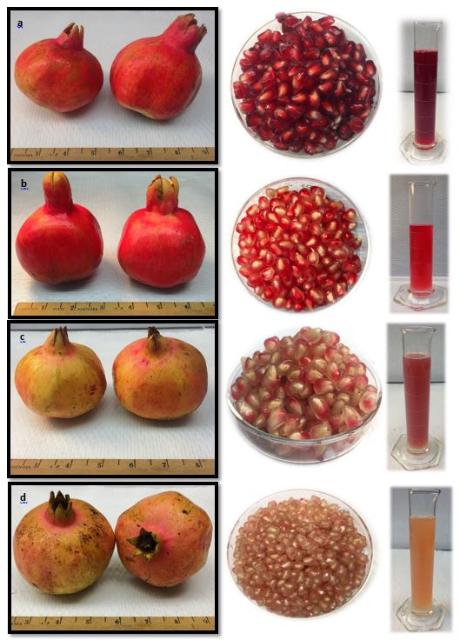

Fruit, aril, and juice characteristics of four pomegranate cultivars grown in Florida; fruit harvested in August 2018. a) ‘Vkusnyi’, b) ‘Crab’, c) ‘Mack Glass’, d) ‘Ever Sweet’. Photo Credit: Ali Sarkhosh, University of Florida/IFAS

A common commercial variety, ‘Wonderful’, is widely grown in California but does not perform well in Florida’s hot and humid climate. Cultivars that have performed well in Florida include: ‘Vkusnyi’; ‘Crab’; ‘Mack Glass’; and ‘Ever Sweet’. Pomegranates are adapted to many soil types from sands to clays, however yields are lower on sandy soils and fruit color is poor on clay soils. They produce best on well-drained soils with a pH range from 5.5 to 7.0. The plants should be irrigated every 7 to 10 days if a significant rain event doesn’t occur. Flavor and fruit quality are increased when irrigation is gradually reduced during fruit maturation. Pomegranates are tolerant of some flooding, but sudden changes to irrigation amounts or timing may cause fruit to split.

Two pomegranate training systems: single trunk on the left and multi-trunk on the right. Photo Credit: Ali Sarkhosh, University of Florida/IFAS

Pomegranates establish best when planted in late winter or early spring (February – March). If you plan to grow them as a hedge (shrub form), space plants 6 to 9 feet apart to allow for suckers to fill the void between plants. If you plan to plant a single tree or a few trees then space the plants at least 15 feet apart. If a tree form is desired, then suckers will need to be removed frequently. Some fruit will need to be thinned each year to reduce the chances of branches breaking from heavy fruit weight.

Anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum sp. to pomegranate fruit. Photo Credit: Gary Vallad, University of Florida/IFAS

Anthracnose is the most common disease of pomegranates. Symptoms include small, circular, reddish-brown spots (0.25 inch diameter) on leaves, stems, flowers, and fruit. Copper fungicide applications can greatly reduce disease damage. Common insects include scales and mites. Sulfur dust can be used for mite control and horticultural oil can be used to control scales.

by Matt Lollar | Sep 7, 2019

A couple weeks ago, I was on a site visit to check out some issues on Canary Island Date Palms. The account manager on the property requested a site visit because he thought the palms were infested with scale insects. He noticed the issue on a number of the properties he manages and he was concerned it was an epidemic. From a distance, lower fronds were yellowing from the outside in and the tips were necrotic. These are signs of potassium deficiency with possible magnesium deficiency mixed in.

Transitional leaf showing potassium deficiency (tip) and magnesium deficiency (base) symptoms. Photo Credit: T.K. Broschat, University of Florida/IFAS Extension

Nutrient deficiencies are slow to correct in palm trees. It’s much easier to prevent deficiencies from occurring by using a palm fertilizer that has the analysis 8N-2P2O5-12K2O+4Mg with micronutrients. Even if the palms are part of a landscape which includes turf and other plants that require additional nitrogen, it is best to use a palm fertilizer with the analysis previously listed over a radius at least 25 feet out from the palms. However, poor nutrition wasn’t the only problem with these palms.

Upon closer look, the leaflets were speckled with little bumps. Each bump had a little white tail. These are the fruiting structures of graphiola leaf spot also known as false smut.

Graphiola leaf spot (false smut) on a Canary Island Date Palm. Photo Credit: Matt Lollar, University of Florida/IFAS Extension – Santa Rosa County

Graphiola leaf spot is a fungal leaf disease caused by Graphiola phoenicis. Canary Island Date Palms are especially susceptible to this disease. Graphiola leaf spot is primarily an aesthetic issue and doesn’t cause much harm to the palms infected. In fact, the nutrient deficiencies observed in these palms are much more detrimental to their health.

Graphiola leaf spot affects the lower fronds first. If the diseased, lower fronds are not showing signs of nutrient deficiencies then they can be pruned off and removed from the site. All naturally fallen fronds should be removed from the site to reduce the likelihood of fungal spores being splashed onto the healthy, living fronds. A fungicide containing copper can be applied to help prevent the spread of the disease, but it will not cure the infected fronds. Palms can be a beautiful addition to the landscape and most diseases and abiotic disorders can be managed and prevented with proper pruning, correct fertilizer rates, and precise irrigation.

by Julie McConnell | Aug 22, 2019

Until plans were underway for our UF/IFAS Demonstration Butterfly Garden, I had never heard of Cutleaf Coneflower, Rudbeckia lacineata. Master Gardener Volunteer Jody Wood-Putnam included this gem in her garden design and introduced me and many of our visitors to a new garden favorite.

Although in the same genus as your common Black-eyed Susan’s (Rudbeckia fulgida or R. hirta) this perennial has very distinct differences. Rather than the low growing, hairy, oblong leaves of Black-eyed Susan, Cutleaf Coneflower has smooth pinnately lobed leaves with serrated edges. The leaves are still clump forming but form an almost bush-like shape. By mid to late summer, tall flower spikes emerge and are covered in bright yellow flowers bringing the overall height of the plant over 5 feet tall!

Cutleaf Coneflower is native to North America with several variations adapted to different regions including the Southeast and Florida. This perennial performs well in full sun to part shade and needs a lot of space. Mature plants can reach 3’ wide by 10’ tall and may require staking. The plant can spread through underground runners, so be sure to give it lots of space. In North Florida leaves may be evergreen if winter is mild. Cutleaf Coneflower is a good wildlife attractant providing nectar and pollen for many insects and if you leave the flowers on to mature the seed the is eaten by songbirds, including goldfinch.

To see this plant in person, stop by the UF/IFAS Demonstration Garden at 2728 E. 14th Street, Panama City, FL. If during normal business hours, check in for available seeds from our Pollinator Garden. 850-784-6105

by Beth Bolles | Aug 7, 2019

We are always on the lookout for an attractive plant for our landscape. At the nursery, some plants have a more difficult time gaining our attention. They may not be as showy, possessing neither colorful flowers nor bold foliage. In these cases, we could be missing out on low maintenance plant that offers its own form of beauty in the right landscape spot.

One plant that I love is the Japanese plum yew (Cephalotaxus harringtonia), especially the spreading form ‘Prostrata’. In the nursery container, this plant is nothing special but once established in the landscape it performs well. The conifer type leaves are an attractive dark green and the ‘Prostrata’ selection is low growing to about 2 to 3 feet. An advantage too is that growth is slow so it won’t take over or require routine pruning.

Japanese plum yews grow best in partial shade and once established will be fine with rainfall. For a shadier side of the home, the spreading plum yew has a place as an evergreen foundation plant too.

Japanese plum yew in a shaded garden. Photo by Beth Bolles, UF IFAS Extension Escambia County

If the ‘Prostrata’ selection is too low growing for you, consider the ‘Fastigiata’ cultivar that will grow upright to about 8 feet with a 5 foot spread.

A year old planting of upright Japanese plum yew in filtered light. Photo by Beth Bolles, UF IFAS Extension Escambia County

by Daniel J. Leonard | May 20, 2019

Spring is a wonderful time of year. After months of dreariness and bare branches, bright, succulent green leaves and flowers of every kind and color have emerged. So too, have emerged gardeners and outdoor enthusiasts ready to tackle all their home and landscape improvement projects planned over the winter. However, this is also the time, when folks first start paying attention to their plants again, that strange, seemingly inexpiable plant problems crop up!

All plant problems can be divided into two categories: biotic problems, or issues caused by a living organism (think insects, fungus, and bacteria), and abiotic problems, issues that arise from things other than biotic pests. It’s the first category that people generally turn to when something goes wrong in their landscape or garden. It’s convenient to blame problems on pests and it’s very satisfying to go to the local home improvement store, buy a bottle of something and spray the problem into submission. But, in many of my consultations with clientele each spring, I find myself having to step back, consider holistically the circumstances causing the issue to arise, scout for pests and diseases, and if I find no evidence of either, encouraging the person to consider the possibility the problem is abiotic and to adopt patience and allow the problem to correct itself. Of course, this is never what anyone wants to hear. We always want a solvable problem with a simple cause and solution. But life isn’t always that easy and sometimes we must accept that we (nor a pest/disease) did anything wrong to cause the issue and, in some cases, that we ourselves actually caused the problem to happen in the first place! To illustrate, let’s consider two case studies from site visits I’ve had this spring.

Cold damage on Boxwood hedge

Three weeks ago, I got a call from a very concerned client. She had gotten her March issue of a popular outdoor magazine in the mail, in which was a feature on an emerging pathogen, Boxwood Blight, a nasty fungus decimating Boxwood populations in states north of us. She had also noticed the Boxwoods in front of her house had recently developed browning of their new spring shoots across most the hedgerow. Having read the article and matching the symptoms she’d noticed to the ones described in the magazine article, she was convinced her shrub was infected with blight and wanted to know if there was a cure. Agreeing that the symptoms sounded similar and wanting to rule out an infection of an extremely serious pathogen, I decided to go take a look. Upon inspection, it was obvious that Boxwood Blight wasn’t to blame. Damage from disease generally isn’t quite as uniform as what I saw. The new growth on top of the hedge was indeed brown but only where the eaves of the house and a nearby tree didn’t provide overhead cover and, to boot, the sides of the hedge were a very normal bright green. Having gone through a recent cold snap that brought several mornings of heavy frost and knowing that the weeks before that the weather had been unseasonably warm, causing many plants to begin growing prematurely, all signs pointed toward an abiotic problem, cold/frost damage that would clear up as soon as the plant put on another flush of growth. The client was delighted to hear she didn’t have a hedge killing problem that would require either adopting a monthly fungicide regime or replacing the hedge with a different species.

Damage to ‘Sunshine’ Ligustrum from pressure washing siding with bleach.

The very next week, another client asked if I would come by her house and take a look at a hedge of ‘Sunshine’ Ligustrum that lines her driveway, whose leaves had “bleached” out, turning from their normal chartreuse to a bronzy white color. This time, having seen similar issues with this particular plant that almost always involved an infestation of Spider or Broad Mites, I figured this was a cut and dry case that would end with a call to her pest control company to come spray the offending bugs. However, though the leaf damage looked similar, I was not able to locate any existing pests or find evidence any had been around recently, rather it appeared the leaves had been exposed to something that “bleached” and burned them. Puzzled, I began asking questions. What kind of maintenance occurs on the plants? Have you fertilized or applied any chemicals recently? Nothing. Then, near the end of our conversation, the client mentioned that her neighbor had pressure washed their house on a windy day and that she was irritated because some of the soap solution had gotten on her car. Bingo. Leaf burn from pressure washing solution chemicals. This time I was guilty of assuming the worst from a pest when the problem quite literally blew in on the wind from next door. Again, the client was relieved to know the plant would recover as soon as a new flush of growth emerged and hid the burned older leaves!

This spring, I’d encourage you to learn from the above situations and the next time you notice an issue on plants in your yard, before you reach for the pesticides, take a step back and think about what the damage looks like, thoroughly inspect the plants for possible insects or disease, and if you don’t find any, consider the possibility that the problem was abiotic in nature! And remember, if you need any assistance with identification of a landscape problem and want research-based recommendations on how to manage the problem, contact your local UF/IFAS Extension office.