by Daniel J. Leonard | Jun 2, 2020

Pineapple Guava (Acca sellowiana) hedge. Photo courtesy of the author.

One of the most common questions I’ve gotten across the Panhandle over the last several years is “What can I plant to screen my house and property?” I surmise this has a lot to do with Hurricane Michael wiping properties clean and an explosion of new construction, but whatever the reason, people want privacy, they want it quickly, and they often want something a little more natural looking and aesthetically pleasing than a fence. Like everything else, the answer to the question is nuanced depending on the site situation. However, if the situation is right, I almost always recommend that clientele at least consider a woefully underutilized plant in the Panhandle, Pineapple Guava (Acca sellowiana).

Named a Florida Garden Select Plant by the Florida Nursery Growers and Landscape Association (FNGLA) in 2009, Pineapple Guava is a standout screening and specimen plant, passing all the usual tests homeowners demand from shrubs. Growing 15’x15’ or so if never pruned or sheared, these quick-growing evergreen shrubs sport pretty, leathery green leaves with gray to white undersides. This leaf underside coloring causes the plants to emit a striking silvery blue hue from a distance, a very unusual feature in the screening shrub world.

Pineapple Guava (Acca sellowiana) silvery blue leaf undersides. Photo courtesy of the author.

Look past the leaves and you’ll notice that Pineapple Guava also possesses attractive brownish, orange bark when young that fades to a pretty, peely gray with age. To complete the aesthetic trifecta, in late spring/early summer (generally May in the Panhandle), the plants, if not heavily sheared, develop gorgeous edible, pollinator-friendly flowers. These flowers, comprised of white petals with bright red to burgundy stamens in the center, then develop over the summer into tasty fruit that may be harvested in the fall.

In addition to being a superbly attractive species, Pineapple Guava is extremely easy to grow. They like full, all-day, blazing sunshine but will tolerate some shading if they receive at least six hours of direct sun. Well-drained soil is also a must. Pineapple Guava, like many of us, is not a fan of wet feet! Site them where excessive water from rain will drain relatively quickly. Adding to its merits, the species is not plagued by any serious pests or diseases and is also drought-tolerant, needing no supplemental irrigation once plants are established. A once a year application of a general-purpose fertilizer, if indicated by a soil test, may be useful in getting plants going in their first couple of years following planting, but is rarely necessary in subsequent years. To maintain Pineapple Guava as a formal hedge or screen, a simple shear or two each growing season is normally enough. The species also makes an outstanding small specimen tree when allowed to grow to its mature height and “limbed-up” to expose the interesting bark and limb structure.

Edible, pollinator-friendly Pineapple Guava flowers in bloom. Photo credit: Larry Williams

If you’ve been looking for a quick-growing, low-maintenance screen or a specimen plant for a large landscape bed, you could do a lot worse than the Florida-Friendly Pineapple Guava! As always, if you have any questions about Pineapple Guava or any other horticulture, agriculture or natural resource related issue, contact your local UF/IFAS County Extension Office!

by Matt Lollar | May 20, 2020

The pawpaw (Asimina triloba) is a native edible that is often overlooked and misunderstood. Not only does it produce a delicious fruit that looks like a mango and tastes like a banana, but it is also an aesthetic landscape plant. This fruit is slowly gaining popularity with younger generations and a handful of universities (Kentucky State University and the University of Missouri) are working on cultivar improvements.

A pawpaw tree growing in the woods. Photo credit: Matt Lollar, University of Florida/IFAS Extension – Santa Rosa County

The pawpaw is native to the eastern United States (USDA Plant Hardiness Zones 5-8), however it’s closest relatives are all tropical such as the custard apple, cherimoya, and soursop. The pawpaw, along with these fruits, are known for their custard-like texture which may be a unpleasant for some consumers. Pawpaws are relatively hardy, have few insect pests, and can still produce fruit in partial shade (although they produce more fruit when grown in full sun).

Pawpaws perform best in moist, well-drained soils with a pH between 5.5 and 7.0. They are found growing wild in full to partial shade, but more fruit are produced when trees are grown in full sun. However, pawpaws need some protection from wind and adequate irrigation in orchard settings. Trees can grow to between 12 feet to 25 feet tall and should be planted at least 15 feet apart. In the Florida Panhandle, flowers bloom in early spring and fruit ripen from August to October depending on variety and weather.

Young pawpaw fruit growing on a small tree. Photo Credit: Matt Lollar, University of Florida/IFAS Extension at Santa Rosa County

A number of improved cultivars of pawpaws have been developed that produce more fruit with more flavor than native seedlings/saplings. The University of Missouri has conducted trials on the following pawpaw cultivars: ‘Sunflower’; ‘PA Golden’; ‘Wells’; ‘NC-1’; ‘Overleese’; ‘Shenandoah’; ‘Susquehanna’; and ’10-35′. Most of these cultivars performed well in southern Missouri, however yields may differ in the Florida Panhandle. The full results of the trial can be found in the “Pawpaw – Unique Native Fruit” publication.

Pawpaws can be propagated by seed or cuttings. Unlike most fruit trees, pawpaws are usually true to seed meaning that saved seed produces a tree with similar characteristics to the parent tree. To save seeds, place fresh seeds in a bag of moist peat moss and refrigerate for 3 to 4 months before planting. To vegetatively propagate, take cuttings (pencil thin in diameter) in the winter and store in a refrigerator until early spring. Cuttings should be chip budded onto seedling rootstock during the spring. Please visit this publication from the University of Nebraska for more information on chip budding.

Pawpaw fruit are ready to harvest when they are slightly soft when gently squeezed. Fruits picked prior to being fully ripe, but after they start to soften, will ripen indoors at room temperature or in a refrigerator. Already-ripe fruit will stay fresh for a few days at room temperature or for a few weeks in the refrigerator. To enjoy pawpaw fruit throughout the year, scoop out the flesh, remove the seeds, and place the flesh in freezer bags and freeze.

Whether you want to add more native plants to your landscape or you are a rare and unusual fruit enthusiast, pawpaw may be the tree for you. They can be utilized as a focal point in the garden and provide delicious fruit for your family. For more information on pawpaw or other fruit trees, please contact your local Extension Office.

by Larry Williams | Apr 23, 2020

One of the things to do while stuck at home due to COVID-19 restrictions, is to look for caterpillars and butterflies in your landscape. I’ve noticed giant swallowtail butterflies (Papilio cresphontes) a little early this year. The giant swallowtail is one of the largest and most beautiful butterflies in our area. Its larval stage is known as the orangedog caterpillar. This unusual name comes from the fact that it feeds on young foliage of citrus trees.

Orangedog caterpillar. Photo credit: Donald Hall, University of Florida

The orangedog caterpillar is mostly brown with some white blotches, resembling bird droppings more than a caterpillar. When disturbed, it may try to scare you off by extruding two orange horns that produce a pungent odor hard to wash off.

I’ve had some minor feeding on citrus trees in my landscape from orangedog caterpillars. But I tolerate them. I’m not growing the citrus to sell. Sure the caterpillars eat a few leaves but my citrus trees have thousands of leaves. New leaves eventually replace the eaten ones. I leave the caterpillars alone. They eat a few leaves, develop into chrysalises and then emerge as beautiful giant swallowtail butterflies. The whole experience is a great life lesson for my two teenagers. And, we get to enjoy beautiful giant swallowtail butterflies flying around in our landscape and still get plenty of fruit from the citrus trees. It is a win, win, win.

In some cases, the caterpillars can cause widespread defoliation of citrus. A few orangedog caterpillars can defoliate small, potted citrus trees. Where you cannot tolerate their feeding habits, remove them from the plant. But consider relocating the caterpillars to another area. In addition to citrus, the orangedog caterpillars will use the herb fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) and rue (Ruta graveolens) as a food source. Some butterfly gardens plant citrus trees to provide food for orangedog caterpillars so that they will have giant swallowtail butterflies. So you could plan ahead and grow some fennel, rue or find a butterfly garden in your area for the purpose of relocating the larvae.

Yellow giant swallowtail butterfly on pink garden phlox flowers. Photo credit: Larry Williams

The adult butterflies feed on nectar from many flowers, including azalea, bougainvillea, Japanese honeysuckle, goldenrod, dame’s rocket, bouncing Bet and swamp milkweed. Some plants in this list might be invasive.

Keep in mind that mature citrus trees can easily withstand the loss of a few leaves. If you find and allow a few orangedog caterpillars to feed on a few leaves of a mature citrus tree in your landscape, you and your neighbors might get to enjoy the spectacular giant swallowtail butterfly.

More information on the giant swallowtail butterfly is available online at http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/in134.

by Matt Lollar | Apr 23, 2020

I was recently sent some pictures of some unusual growths on pecan tree leaves. At first glance, the growths reminded me of the galls caused by small wasps that lay their eggs on oak leaves. However, after a little searching it became apparent this wasn’t the case. These galls were caused by the feeding of an aphid-like insect known as phylloxera.

Leaf galls caused by pecan phylloxera. Photo Credit: Matt Lollar, University of Florida/IFAS Extension – Santa Rosa County

The feeding from the phylloxera causes the young leaf tissue to become distorted and form a gall that encloses this female insect called a “stem mother”. These insects are rarely seen, but the hatch from over-wintering eggs in March/April just after budbreak. Once hatched, these “stem mothers” crawl to the new leaves and begin feeding. Once the gall forms, they start to lay eggs inside the gall. The eggs hatch inside the gall and the young phylloxera begin to feed inside the gall and the gall enlarges. The matured insects break out of the gall in May and some will crawl to new spots on the leaves to feed and produce more galls.

Pecan stem damage from phylloxera. Photo Credit: University of Georgia

There are two common species of phylloxera that infect the leaves. The Pecan Leaf Phylloxera seems to prefer young trees and the Southern Pecan Leaf Phylloxera prefers older trees. The damage from each of these insects is nearly indistinguishable. Damage from these insects is usually not severe and merely an aesthetic issue.

Once the damage is discovered on a tree, it is too late to control the current year’s infestation. There are currently no effective methods for control of phylloxera in home gardens. Soil drench applications witha product containing imidacloprid have been limited in their effectiveness.

by KR Woodburn | Jan 31, 2020

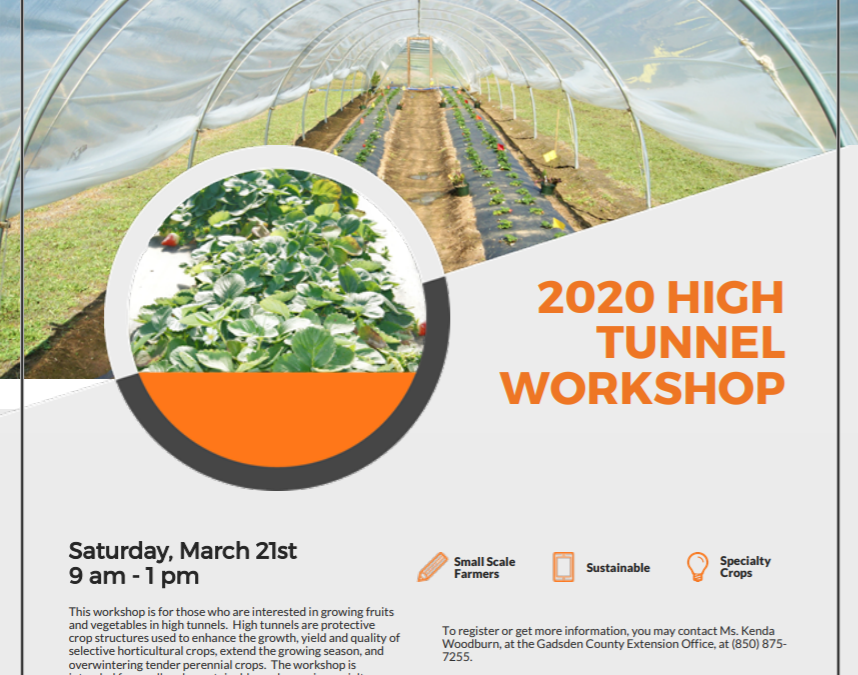

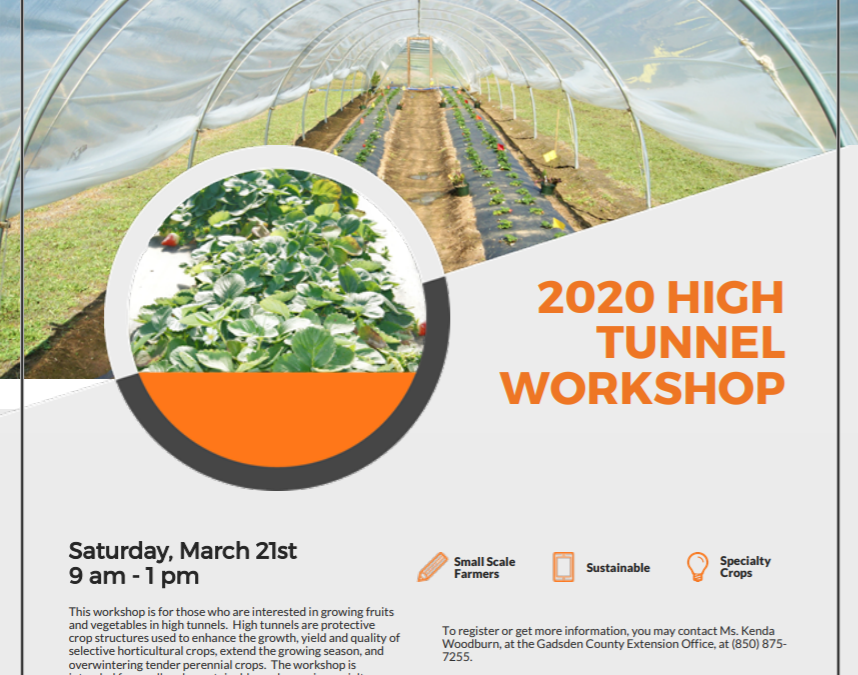

2020 High Tunnel Workshop

March 21, 2020

Agenda

- 9 A.M. Welcome

Mrs. Vonda Richardson, FAMU Extension, Director

- 9:10 High Tunnels: Site and Crop Selection Considerations for High Tunnels

Dr. Alex Bolques, FAMU Extension/REC – Utilizing Floating Row Covers to Exclude Insect Pests and Increase

Winter Protection in High Tunnels – Ms. Kenda Woodburn, FAMU Extension Agent, Gadsden County

- 9:30 Integrated Management Practices for High Tunnel Organic Vegetable

Production -Dr. Xin Zhao, UF Horticultural Sciences

Hot Pepper, Strawberry, and Leafy Green Production in Protective

Structures -Dr. Gilbert Queeley and Alex Bolques, FAMU Extension

- 10:20 Break

- 10:30 Monitoring and Management of Pest and Beneficial Insects in the High Tunnel Production Systems – Dr. Muhammad Haseeb, FAMU Center for Biological Control

- Cultural Management of Insect Pests: Plant-mediated Push-Pull Technology – Dr. Susie Legaspi, ARS Research Entomologist

- 11:20 Field Demonstration: Protected Ag

- Short walk to high tunnel areas

– Leafy greens production using organic methods

– Sustainable strawberry production using organic methods

– Low cost high tunnel structural improvements

– Strawberry season extension

– Selective vegetable hydroponic production systems

- 12:30 Lunch and Learn:

High Tunnel Cost Sharing Opportunities

Mrs. Karyn Ruiz-Toro, NRCS District Conservationist

Resources & Supplies for High Tunnel Growers

Ms. Kenda Woodburn, FAMU Extension

1 P.M. Adjourn

by Matt Lollar | Dec 10, 2019

Loquat trees provide nice fall color with creamy yellow buds and white flowers on their long terminal panicles. These small (20 to 35 ft. tall) evergreen trees are native to China and first appeared in Southern landscapes in the late 19th Century. They are grown commercially in subtropical and Mediterranean areas of the world and small production acreage can be found in California. They are cold tolerant down to temperatures of 8 degrees Fahrenheit, but they will drop their flowers or fruit if temperatures dip below 27 degrees Fahrenheit.

A beautiful loquat specimen at the UF/IFAS Extension at Santa Rosa County. Photo Credit: Matt Lollar, University of Florida/IFAS – Santa Rosa County

Leaves – The leaf configuration on loquat trees is classified as whorled. The leaf shape is lanceolate and the color is dark green with a nice soft brown surface underneath. These features help give the trees their tropical appearance.

Flowers – 30 to 100 flowers can be present on each terminal panicle. Individual flowers are roughly half an inch in diameter and have white petals.

Fruit – What surprises most people is that loquats are more closely related to apples and peaches than any tropical fruit. Fruit are classified as pomes and appear in clusters ranging from 4 to 30 depending on variety and fruit size. They are rounded to ovate in shape and are usually between 1.5 and 3 inches in length. Fruit are light yellow to orange in color and contain one to many seeds.

A cluster of loquat flowers/buds being pollinated by a honey bee. Photo Credit: Matt Lollar, University of Florida/IFAS – Santa Rosa County

Propagation – Loquat trees are easily propagated by seed, as you will notice as soon as your tree first bears fruit. Seedlings pop up throughout yards containing even just one loquat tree. It is important to note that the trees do not come true from seed and they go through a 6- to 8-year juvenile period before flowering and fruiting. Propagation by cuttings or air layering is more difficult but rewarding, because vegitatively-propagated trees bear fruit within two years of planting. Sometimes mature trees are top-worked (grafted at the terminal ends of branches) to produce a more desirable fruit cultivar.

Loquat trees are hardy, provide an aesthetic focal point to the landscape, and produce a tasty fruit. For more information on growing loquats and a comprehensive list of cultivars, please visit the UF EDIS Publication: Loquat Growing in the Florida Home Landscape.