by Matt Lollar | Jun 21, 2018

Are you interested in growing squash in your garden? Do you know the difference between summer squash and winter squash? Check out this very informative instructional video on growing squash in your home garden by Walton County Agriculture Agent Evan Anderson.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hlbJfV-0FuU&w=560&h=315]

by Mark Tancig | Jun 4, 2018

In north Florida, the arrival of warm weather and plenty of rain means it’s time to battle the mosquitoes again. Those pesky little blood-suckers are out and about, often keeping us from enjoying our outdoor pursuits. With some preventative steps, you can reduce the potential for mosquitoes to occur in your yard.

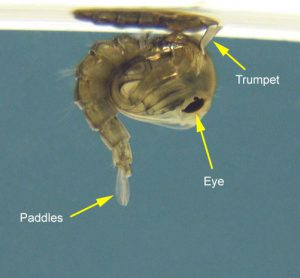

Mosquito larvae. Credit: Florida Medical Entomology Laboratory.

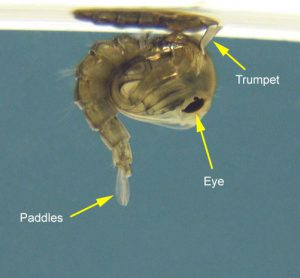

As we should all be aware of by now, mosquitoes require water to complete their lifecycle. Eggs are laid near the water and will dry out if they do not remain near a water source. The larvae, or “wrigglers”, that hatch from the eggs, are aquatic and will not survive out of water. The pupae, often called “tumblers”, are also aquatic and must be in water to survive. From the pupae hatch the adults, the growth stage we want to avoid.

Mosquito pupae. Credit: Florida Medical Entomology Laboratory.

The best method to reduce mosquitoes in your yard is to remove or empty water-holding containers. This prevents the conditions needed for the egg through pupae stages to survive. These water-holding containers can include birdbaths, old buckets, gutters, tarps, rain barrels, and a variety of other items. Even a small bottlecap is enough to breed mosquitoes. Regularly emptying these water-holding containers every 3 to 5 days will stop that most annoying final life stage – the biting adults.

Another way to prevent the aquatic stages of mosquitoes from thriving is to use a larvaecide, specifically Bti. Bti is a bacterium that is sold as either small dunks or doughnuts and can also be found as small granules. Placing a dunk or a few granules in a birdbath will prevent larvae from developing and won’t harm the birds or other organisms that may visit, including frogs, bees, butterflies, and mammals. Bti is a selective pesticide, only effective for control of mosquito, midge, and fungus gnat larvae.

Various mosquito breeding habitats. Credit: Mark Tancig, UF/IFAS

Even if you’ve cleaned up or drained all water-holding containers on your property, there will likely still be some adult mosquitoes looking for a bloodmeal. Wearing long pants and sleeves, using mosquito repellents, and keeping window screens in good order are effective methods to prevent being bitten.

Local mosquito control agencies will often provide services to fog for adults. However, this will want to be your last resort, as the pesticides used to control adults are not as selective as the Bti used for the larvae. This results in non-target damage, meaning that insects besides mosquitoes, including beneficial insects, may also be harmed. Therefore, controlling mosquitoes during their aquatic lifestages helps reduce the need for pesticides that can harm beneficial insect populations.

The UF/IFAS Florida Medical Entomology Laboratory Research and Education Center has a great website – https://fmel.ifas.ufl.edu/ – of mosquito-related information, including the various species of mosquitoes in Florida and which repellents work the best. For additional information on controlling mosquitoes and other pests, please contact your local Extension Office.

by Julie McConnell | May 23, 2018

Dr. Steve Johnson, UF/IFAS Associate Professor of Wildlife Ecology will be the featured speaker on June 6th

June 6th is a great day to learn about all types of invasive species that threaten natural areas in Northwest Florida!

The UF/IFAS Extension Bay County office will have multiple educational exhibits with living samples of species of concern from 9 a.m. – 5 p.m. on Wednesday, June 6th. This is a multi-agency effort to inform citizens about the impact of invasive plants and animals and how they can help reduce introduction and spread. For full details see the Bay_Invasive Workshop Flyer

We are pleased to announce our partners Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) and Science and Discovery Center of Northwest Florida will be on hand to share information about caring for exotic pets and current management plans for invasive species such as Lionfish, Aquatic Weeds, and how to surrender an animal on designated Pet Amnesty Days.

At noon there will be a special guest speaker for a bring your own lunch & learn “Exotic Invaders: Reptiles and Amphibians of Concern in NW FL.” Dr. Steven Johnson, UF/IFAS Associate Professor of Wildlife Ecology, will talk about exotic reptiles and amphibians we should be aware of that may occur in our area.

In the morning, we will be focusing on the invasive air potato vine with the distribution of air potato leaf beetles for biological control. Need air potato leaf beetles to manage the air potato vine on your property? Please register here http://bit.ly/bayairpotato to receive beetles – they will be distributed from 9 a.m. – noon on June 6th.

Learn more about the success of the Air Potato Biological Control program at http://bcrcl.ifas.ufl.edu/airpotatobiologicalcontrol.shtml

#invasivespecies

by Molly Jameson | May 23, 2018

Air potato leaf beetle attacking the invasive air potato plant.

Air potatoes got you down? Have no fear, for the Air Potato Challenge is coming to Leon County!

Register now to attend the Air Potato Challenge event on May 18, 9 a.m. to 12 p.m. at the FAMU Center for Viticulture and Small Fruit Research (6361 Mahan Drive, Tallahassee, FL) and receive a supply of air potato beetles to use on your property.

After years of testing, air potato beetles became available as a biological control in 2012 to help combat the invasive herbaceous perennial air potato vine (Dioscorea bulbifera). Air potatoes arrived in south Florida from China in the early 1900s and have steadily crept north until they are now invading the Panhandle Region. Fortunately, air potato beetles have dietary requirements that are very specific, relying strictly upon air potatoes to complete their life cycles.

This is why a team of researchers and Extension agents have come together to help spread air potato beetles as a biological control strategy. Many agencies and counties are involved in this effort, including UF/IFAS Extension St. Lucie County, UF/IFAS Indian River Research and Education Center, the Florida Department of Agriculture Division of Plant Industry, the USDA, Florida Fish and Wildlife, UF/IFAS Extension Leon County, and Florida A&M University.

From 9 a.m. to noon on May 18, Florida residents and public land managers are invited to come out to the FAMU Center for Viticulture and Small Fruit Research to get more information about the invasive air potato and its biological controller, the air potato beetle, and receive a supply of beetles to use on their properties. Please pre-register on the Eventbrite page (https://www.eventbrite.com/e/may-18-2018-air-potato-challenge-leaf-beetles-available-for-the-public-leon-county-fl-tickets-44793035174).

You can find more information about air potatoes and air potato beetles on the UF/IFAS Solutions for Your Life Air Potato Biological Control page (http://bcrcl.ifas.ufl.edu/airpotatobiologicalcontrol.shtml).

What: Air Potato Challenge

Where: FAMU Center for Viticulture and Small Fruit Research, 6361 Mahan Drive, Tallahassee, FL

When: May 18, 2018, 9 a.m. to 12:00 p.m.

Cost: Free of charge, but please pre-register

Registration: https://www.eventbrite.com/e/may-18-2018-air-potato-challenge-leaf-beetles-available-for-the-public-leon-county-fl-tickets-44793035174

by Sheila Dunning | Apr 23, 2018

With cool, foggy mornings you may have noticed the large number of spider webs hanging on low vegetation. Some of them have unusual shapes. One of the most notable is the bowl and doily spider. This spider (Frontinella pyramitela) is a species of sheet web weavers found throughout the United States, including Northwest Florida.

It is a small spider, about 3-4 mm (0.16 in) long, boldly marked with black and white stripes on the abdomen, a brown cephalothorax, and brownish legs. They weave a fairly complex shaped webs only a few inches across, usually well off the ground and stretched between twigs or other objects. Webs consist of an inverted dome-shaped web, or “bowl”, suspended above a horizontal sheet web, or “doily”, hence its common name. The webs are approximately circular when viewed from above, where there is a tangled scaffold “knock down” threads of silk invisible to flying insects. The webs are commonly seen in weedy fields and in shrubs.

It is a small spider, about 3-4 mm (0.16 in) long, boldly marked with black and white stripes on the abdomen, a brown cephalothorax, and brownish legs. They weave a fairly complex shaped webs only a few inches across, usually well off the ground and stretched between twigs or other objects. Webs consist of an inverted dome-shaped web, or “bowl”, suspended above a horizontal sheet web, or “doily”, hence its common name. The webs are approximately circular when viewed from above, where there is a tangled scaffold “knock down” threads of silk invisible to flying insects. The webs are commonly seen in weedy fields and in shrubs.

Small flies, gnats and other small insects crash into the strands of barrier silk and fall down into the non-sticky webbing. The spider hangs from the underside of the “bowl”, and bites through the web, pulling the prey through in order to consume them while resting comfortably on the “doily”. Bowl and doily spiders serve a very important ecological role by controlling human-biting and plant damaging insects.

Among web-building spiders, bowl and doily spiders (Frontinella pyramitela) are unusual because both males and females often cohabitate. The males rarely build webs, however, and so depend upon females ‘ snares for food. These cohabiting males capture about 32% of the prey that hit the web despite the female’s efforts to capture the same prey.

Among web-building spiders, bowl and doily spiders (Frontinella pyramitela) are unusual because both males and females often cohabitate. The males rarely build webs, however, and so depend upon females ‘ snares for food. These cohabiting males capture about 32% of the prey that hit the web despite the female’s efforts to capture the same prey.

Mating in this species occurs on the underside of the bowl of the female’s web and is preceded by a complex vibration- and chemical-mediated courtship during the late summer. Eggs are laid in silken sacs in the web or hiding in leaf litter on the ground. Both eggs and adults have been known to overwinter. Like all spiders, bowl and doily spiders develop through simple metamorphosis: spiderlings look like tiny adult spiders (but with lighter coloration), and shed their outer skin in order to grow. Most sheet web weavers live only one year.

by Beth Bolles | Apr 9, 2018

The change in North Florida temperatures from cooler to warmer is making many winter weeds more noticeable as they begin to flower and form seed. Not all of these plants should be considered for mowing or hand pulling. There are several wildflowers that grow in landscape beds and thinning areas of lawns and can be enjoyed before consistent heat returns.

Toadflax flowers are held above the foliage and are light purple. Photo by Beth Bolles, UF IFAS Extension Escambia County

One very delicate wildflower that is growing now is the Toadflax, Linaria canadensis. The leaves are very small and grow low on the ground. Thin flower stalks grow several inches and are topped with light purple flowers. Although toadflax pops up in beds and lawns don’t be so quick to pull it out. This wildflower is a host to the Buckeye butterfly, one of our earlier visitors to gardens. If you look closely you may even see the tiny black, spiny caterpillar eating toadflax leaves. Visit the UF publication on the Buckeye butterfly to learn more.

Adult buckeye butterflies are common in landscapes in early spring and late summer. Photo by Lo Sitton, UF IFAS Extension Escambia County