by Sheila Dunning | Aug 31, 2020

Photo from USDA APHIS

Remember last year’s vacation trip? You picked the perfect location, checked into the hotel and made sure to check every mattress corner for bedbugs. Bugs can hide in the strangest places. Now with COVID-19 those people insisting on still taking a vacation are flocking to Northwest Florida. While some are still utilizing hotels, the majority are pulling into the RV park or campground. They are bringing anything and everything anyone could possibly need for the week, from firewood to camp chairs. That way no one will have to go to the store. Somewhere on the vehicle or within all the stuff there may be some hitchhikers, insect stowaways. The problem is that these bugs may be staying even after the human beings head back north. Florida is notorious for invasive species. With 22 international airports and 15 international ports in the state, hundreds of foreign insects are intercepted each month. But, not all the problem creepy crawlers are coming from the south. Many have been introduced to northern states and work their way here.

One to keep an eye open for is spotted lanternfly (Lycorma delicatula). The Asian native was first detected in Pennsylvania in 2014. Since then it has spread to the east and south. While the insect can walk, jump, or fly short distances, the quickest way for the spotted lanternfly to relocate is to lay eggs on natural and man-made surfaces. Some of those egg masses may fall off and get left at the park. Next spring after the eggs hatch the nymphs will begin feeding on the sap of numerous plants, often changing species as they mature. Host plants include grape, maple, poplar, willow and many fruit tree species.

Nymphs in the early stages of development appear black with white spots and turn to bright red before becoming adults. At maturity spotted lanternflies are about 1 ½ inches wide with large colorful, spotted wings.

Photo from USDA APHIS

At rest their forewings are folded up giving the lanternfly a dull light brown appearance. But when it takes flight its beauty is revealed. The bright red hind wings and the yellow abdomen are very eye-catching. Remember, in nature bright colors are often a warning. Though spotted lanternflies are attractive, they pose a valid threat to native and food-producing plants. The adults feed by sucking sap from branches and leaves. What goes in must come out. Sugar in, sugar out. Spotted lanternflies excrete a sticky, sugar-rich fluid referred to as honeydew. Black sooty mold often develops on honeydew covered surfaces.

Spotted lanternflies are most active at night, steadily migrating up and down the trunk of trees. During the day they tend to gather together at the base of the plants under a canopy of leaves. So, you may need your lantern (or head lamp) to locate them. If you find an insect that you suspect is a spotted lanternfly, please contact your local Extension office of the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services Division of Plant Industries.

Photo by USDA APHIS

by Daniel J. Leonard | Jul 29, 2020

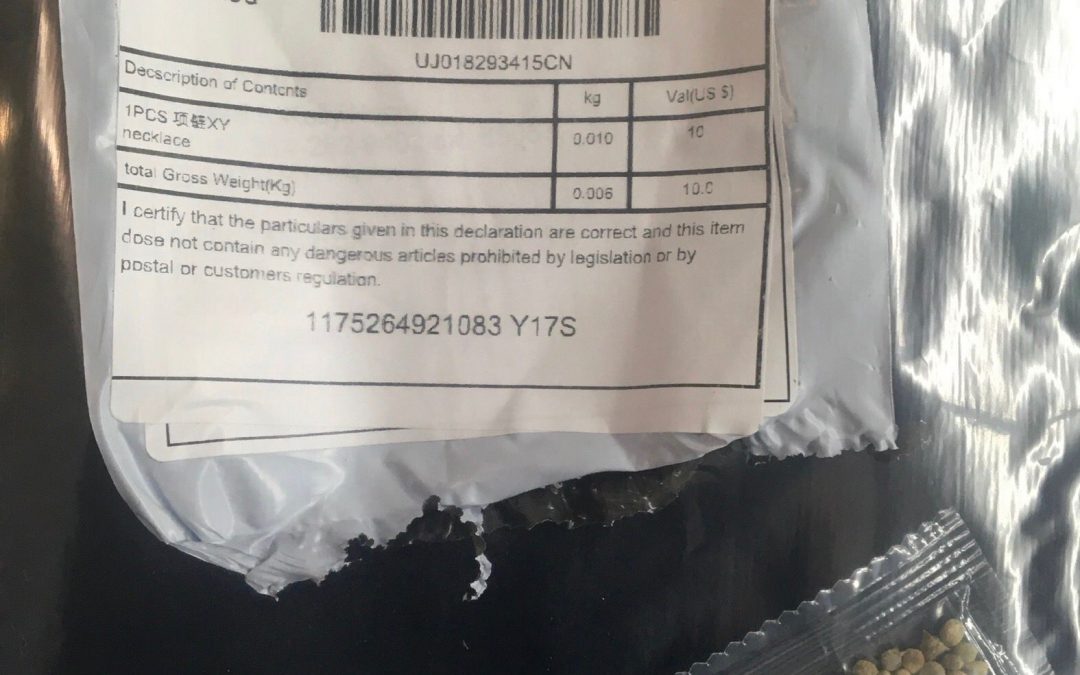

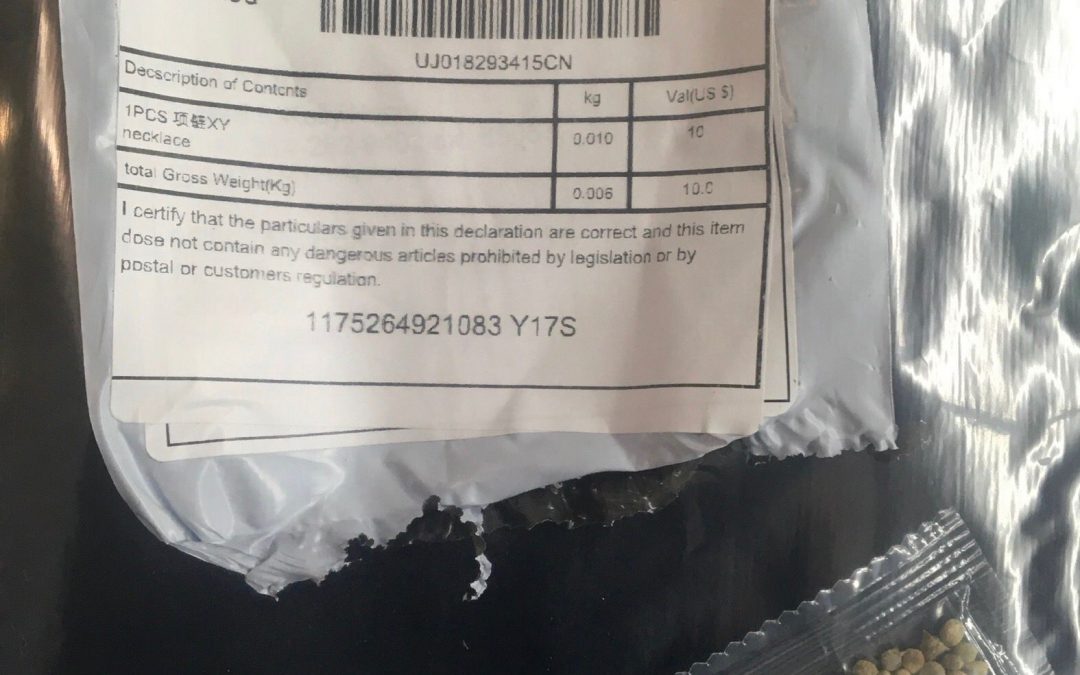

If you’ve paid attention at all to the news recently or been on social media, you’ve no doubt seen the flood of stories about mysterious seeds arriving in thousands of Americans’ mailboxes from various addresses in China. The packages may be labelled as jewelry or other common items, may have postage written in Chinese characters and have been documented in multiple states, including Florida. Little else is currently known about the seed packages and it has not yet been documented if the seeds are harmful invasive species or carry other pathogenic organisms that could wreak havoc on local ecosystems. The illicit introduction of seeds from abroad is a serious concern and is being closely monitored and investigated nationally by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) and locally by the Florida Department of Agriculture (FDACS) Division of Plant Industry.

Photo courtesy of the Kentucky Department of Agriculture.

How or why these seeds have made it to Floridian’s doorsteps and P.O. boxes is still anyone’s guess, but the bottom line is that the shipping of undocumented plant material into and out of the U.S. is illegal and potentially hazardous to people, the economy, and the environment. Here’s what to do if one of these packages of seeds shows up in your mailbox:

- Do not open the seed packets and avoid opening outer packaging or mailing materials.

- Do not plant any of the seeds.

- Do not dispose of the seeds; releasing them into our local ecosystems could prove harmful.

- Limit contact with the seed package until further guidance on handling, disposal, or collection is available from USDA.

- Report the seeds to your local UF/IFAS Extension office. Your local Extension Agent will be able to help you document and ensure that the seeds are reported to the correct authorities.

- Make sure the seeds get also get reported to the FDACS Division of Plant Industry at 1-888-397-1517 or online at DPIhelpline@FDACS.gov

by Mark Tancig | Jul 9, 2020

North Florida vegetable gardeners have made it to summer and now the plants and gardeners are starting to give in to the heat and humidity. The squash has likely succumbed to squash vine borers, many of the tomato varieties are having trouble setting fruit, stink bugs are all over, and gardeners easily wilt by noon. This is a good time to use our oppressive heat to your advantage in the vegetable garden by solarizing the soil.

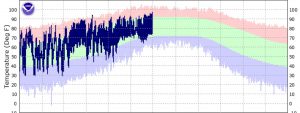

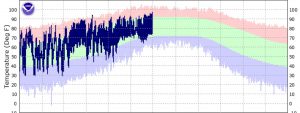

We have reached the peak of heat. Use it to your advantage in the garden. Source: National Weather Service.

Soil solarization is a method of pest control that creates a greenhouse to heat up the soil in an effort to drive away pests. Pests that can be reduced with soil solarization include weeds, various soil-borne fungal pathogens, and nematodes. Weed seeds can actually be killed by the increased temperatures, sometimes as high as 140 degrees Fahrenheit, while fungi and nematodes are merely driven deeper into the soil layer as they try to escape the heat. Although they are not killed, this can help vegetable gardeners as it may take these organisms 3-4 months to repopulate in high enough numbers to cause damage. Soil solarization can be considered another tool in your integrated pest management (IPM) toolbox, along with other cultural, physical, and chemical means of pest control.

A raised bed being solarized over the summer. Source: Evelyn Gonzalez, UF/IFAS Master Gardener Volunteer.

To properly execute soil solarization, the site should be in full sun and the existing vegetation removed, either by hand or with a tiller or other implement. Tilling can help loosen the soil surface and allow heat to penetrate deeper in the soil horizon. Before being covered with plastic, the area should receive rainfall or be irrigated, as the water will help conduct heat to greater depths. The next step is to cover the area with plastic. Note that this can also be done over raised beds! Clear plastic is best for maximum solar radiation penetration. Black plastic will heat up mostly on the surface and opaque plastic sheeting may not let enough light in to get temperatures high enough. The plastic should be slightly larger than the area covered, as the edges will need to be buried to create an air-tight seal. It’s recommended to leave the plastic in place for at least six to eight weeks, just in time to begin fall gardening preparations.

It’s important to monitor the site while it’s “cooking” to look for any holes that might appear. Small holes can be repaired with duct tape, while large holes or rips in the plastic may require starting over. Overlapping strips of plastic is not recommended since too much heat will be lost.

You may be wondering what happens to all of the good soil microbes. Well, unfortunately, they are also either killed or suppressed. Fortunately, researchers have found that they are able to repopulate quicker than the pest organisms, especially in soils with a good amount of organic matter.

Much more information on soil solarization can be found in these two documents:

Introduction to Soil Solarization – https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/IN/IN85600.pdf

Solarization for Pest Management in Florida – http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/IN/IN82400.pdf

Also, please contact your local county extension office for more gardening tips.

by Carrie Stevenson | Jun 4, 2020

Fig. 1 An adult redbay ambrosia beetle compared to the size of a single penny. Credit: UF/IFAS File Photo.

While most bark beetles are important in forest ecology by recycling fallen dead trees and eliminating sick and damaged trees, some of them may impact healthy trees. A group of bark beetles that has become a major concern to forest managers, nurseries, and homeowners is the ambrosia beetle. Ambrosia beetles are extremely small, 1-2 mm in length, and live and reproduce inside the wood of various species of trees (Fig. 1). Ambrosia beetles differ from other bark beetles in that they do not feed directly on wood, but on a symbiotic fungus that digests wood tissue for them. Every year, non-native species of ambrosia beetles enter the United States through international cargo and we have now nearly forty non-native species of ambrosia beetles confirmed in the United States. Among them, the redbay ambrosia beetle (Xyleborus glabratus), originally from Southeast Asia, is the vector of the fungal pathogen causing laurel wilt, a disease that devastated the Lauracaea population in the southeastern USA, killing millions of redbay, swamp bay, sassafaras and silk bay.

Fig. 2: A mature dooryard avocado tree with large sections of dead and missing leaves, caused by laurel wilt disease. Summer 2009 Impact Magazine image. Credit: UF/IFAS File Photo.

When these beetles attack a laurel tree, the symbiotic fungus is vectored to the tree’s sapwood after the beetle has tunneled deep into the tree’s xylem, actively colonizing the tree’s vascular system. This colonization leads to an occlusion of the xylem, causing wilting of individual branches and in a matter of weeks progresses throughout the entire canopy, eventually leading to tree death (Fig. 2). The laurel wilt disease has spread rapidly after the vector was first detected in Georgia in 2002. The redbay ambrosia beetle was first detected in Florida in 2004, in Duval County, attacking redbay and swamp bay trees. At this point, it is estimated that more than one-third of redbay in the U.S.A., 300 million trees, have succumbed to the disease.

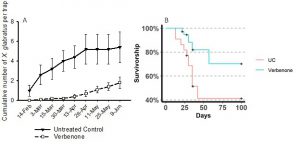

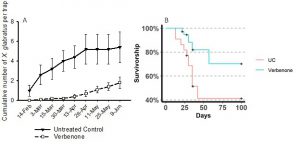

Starting in 2017, we examined the efficacy of verbenone against redbay ambrosia beetle in live laurel trees in a natural forest setting. Verbenone is an anti-aggregation pheromone that has been used since the 1980’s to protect lodgepole pine. Verbenone also has the potential to be used over large areas and is currently being used to protect ponderosa pine plantations from the Mountain Pine Beetle in the western US.

We have found verbenone to be an environmentally friendly and safe tool to prophylactically protect laurel trees against redbay ambrosia beetle. Our protocol consists of the application of four 17 g dollops of a slow-release wax based repellent (SPLAT Verb®, ISCA technology of Riverside, CA) to the trunk of redbay trees at 1 – 1.5 m above ground level (Fig. 3). The wax needs to be reapplied every 4 months during fall and winter and every 3 months during spring and fall when temperature is higher. When compared to the control trees without repellents, we found that trunk applications of verbenone reduced landing of the redbay ambrosia beetle on live redbay trees and increased survivorship of laurel trees compared to untreated trees (Fig. 4). Verbenone should be considered as part of a holistic management system against redbay ambrosia beetle that also includes removal and chipping of contaminated trees.

If you have Redbay or other bay species on your property and are concerned about Laurel Wilt Disease or Redbay Ambrosia Beetle damage, contact your local UF/IFAS Extension Agents for help!

This article is courtesy of Dr. Xavier Martini and Mr. Derek Conover of the UF/IFAS North Florida Research and Education Center (NFREC) in Quincy.

Fig. 3: Application of SPLAT Verb on a redbay tree during a field trial

Figure 4: (A): Cumulative capture of redbay ambrosia beetles Xyleborus glabratus following a single application of verbenone vs untreated control (UC). (B) Survivorship of redbay and swamp bay trees treated with verbenone on four different studies conducted in 2017 and 2018.

by Evan Anderson | May 20, 2020

Next week (May 18-22) is Florida Invasive Species Awareness Week! Join us online for an educational video each day at 9:00 am CST on invasive species that are important in our area and what to do about them. See the flyer below and join us on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/PanhandleOutdoorsNews/ for the event!

Invasive species are living things that are not from an area and have adverse affects on people, whether it is their health, the economy, or the environment we live in. The more people who can identify and control these species, the healthier we can keep ourselves, our businesses, and the world around us!

by Mary Salinas | Apr 29, 2020

Swarm of eastern subterranean termites. Photo by Susan Ellis, Bugwood.org.

Spring is in the air and that means termite swarming season is near!

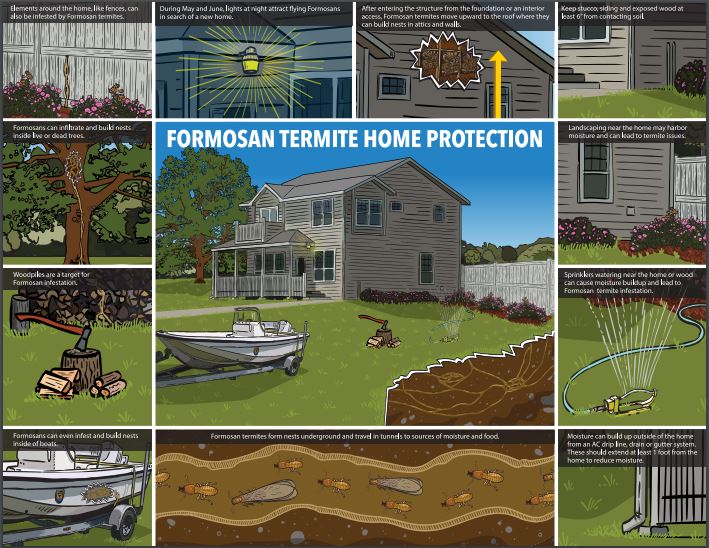

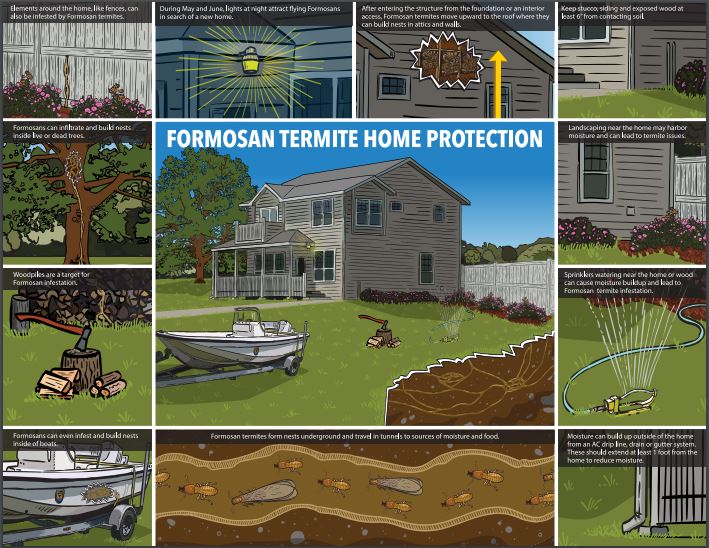

Northwest Florida is home to fifteen native species of termites and six species that have invaded from other parts of the world. One invasive species of termite, the Formosan termite, arrived in the southeastern United States in the 1950’s and has been expanding its range and numbers ever since. While our native termites have colonies in the thousands of individuals, Formosan termite colonies can contain millions of individuals and that makes them a greater threat if they invade your home.

Here are some steps you can take to protect your home:

- Turn off outside lights during termite swarming season – late April through June – the swarms are attracted to the light and may then find entry into your home.

- Reduce moisture around your home by keeping gutters clean and having them drain at least a foot away from the foundation.

- Avoid irrigation hitting the house.

- Plants and mulch should be a foot away from the foundation.

- Repair leaks and cracks – termites can get into the smallest of spaces.

- Avoid wood, stucco and siding in contact with the ground.

- Have an annual inspection by a licensed pest control company. Read the fine print of what is covered and what species/type of termites are included. Some policies exclude coverage for Formosan termites.

For more information:

Subterranean Termites

The Facts About Termites and Mulch

UF/IFAS Featured Creature: Formosan Termites

Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services Termite Control Information

Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services Formosan Termite Program