by Matt Lollar | Apr 1, 2021

If you’ve been raking leaves recently, you’ve probably noticed little green worms hanging from the trees. They seem to be in abundance this year and can be found crawling on driveways, just hanging around, and maybe even feeding on oak tree leaves.

These green worms that are all over the yard are oak leafrollers (Archips semiferanus) or oak leaftiers (Croesia semipurpurana). Some people may refer to them as inchworms, however a number of different caterpillars can go by that name. Leafrollers and leaftiers range in length from 1/4″ to 1″. The adult form of these insects is a 1/2″ long moth. The oak leafroller moth is mottled tan and brown and the oak leaftier moth is yellow with brown markings.

An oak leafroller caterpillar crawling on a leaf. Photo Credit: Blair Fannin, Texas A&M University

In May, the adults of both species lay their eggs in the twigs and leaf buds of a number of tree species. The eggs don’t hatch until March of the following year. When the caterpillars emerge, they feed on the newly forming leaves and flowers of oak, hackberry, pecan and walnut trees. If they are disturbed, they will stop feeding and hang from a strand of silk. Oak leafroller caterpillars pupate in tree branches, while oak leaftier caterpillars drop to the ground and pupate in leaf litter. Adult moths emerge in one to two weeks.

A leafroller moth with wings spread. Photo Credit: U.S. National Museum

The oak leafrollers and oak leaftiers don’t really do enough damage to be considered pests, but they are a bit of a nuisance. Thankfully, birds and parasitic wasps will eat and kill the majority of the population. For in-depth information on most of the interesting insects in your yard, please visit the UF/IFAS Featured Creatures Website.

by Larry Williams | Mar 25, 2021

As a boy in a small town in Georgia we had a St. Augustinegrass lawn. My dad started the lawn before I was born. That lawn was still doing fine when I left for college at age seventeen. I don’t remember weeds in the lawn during summer months. I do fondly remember winter “weeds” in that lawn.

To see clumps of winter annuals in our yard and in neighbors’ yards was a natural part of the transition from winter to spring. They added interest to what

Blue Easter egg hidden in chickweed. Photo credit: Larry Williams

would have been a plain palette of green. It was expected to see henbit with its square stiff stems holding up a display of small pinkish purple flowers in late winter and early spring. A clump of henbit was a great place to hide an Easter egg, especially a pink or purple one.

Wild geranium, another common winter annual, offered another good hiding place for Easter eggs with its pink to purple flowers. Large clumps of annual chickweed would nicely hide whole eggs. Green colored eggs would blend with chickweed’s green leaves.

Pink Easter egg hidden in crimson clover & hop clover mix. Photo credit: Larry Williams

Crimson clover with its reddish flowers, hop clover and black medic with their bright yellow flowers were good hiding places for Easter eggs. Plus clovers add nitrogen back to our soils.

I never remember my dad using any weed killer, he rarely watered. The lawn was healthy and thick enough to be a deterrent to summer weeds. But during fall and winter as the lawn would naturally thin and go dormant, winter annual weeds would run their course.

I’ve heard that the sense of smell provides our strongest memories. I remember the first mowing of the season with the clean smell of chlorophyll in the spring air. It was refreshing. Once mowed and as the heat took its toll, by late April or mid-May, these winter annual weeds were gone. What was left was a green lawn to help cool the landscape as the weather warmed. The lawn was mowed high as St. Augustine should be, played on and typically not worried with.

Most people have winter weeds in their lawns that let us know spring is near. Perhaps we worry too much with these seasonal, temporary plants that may have wrongly been labeled as weeds. Besides, how long have we been doing battle with these weeds and they are still here. Most lawns have countless numbers of winter annual seeds awaiting the cooler temperatures and shorter days of early winter to begin yet another generation. By May they are gone.

by Matthew Orwat | Mar 25, 2021

Stinkbugs and their relatives are not always problematic in the flower or vegetable garden, but when they become so, they can suck the life out of our fruits and vegetables, create ugly abrasions, and destroy flowers such as roses.

Over-wintering adult leaffooted bug emerging from hibernation . Image Credit Matthew Orwat, UF / IFAS Extension

The green stink bug Acrosternum hilare (Say). Image and caption credit EDIS, Dr. Russ Mizell

What is a Stink Bug?

The stink bug (Pentatomidae family) is a major garden pest of a variety of fruits and vegetables including squash, peppers, tomatoes, peaches, plums, pecans and a variety of other edibles. They are known as a “piercing and sucking” insect because that’s the way they feed, by using their mouth, or proboscis, just like a needle to pierce the fruit and suck out the juices. This feeding leaves a damaged area of the fruit which may develop discoloration, rot or fungal disease and render the fruit unsaleable or inedible.

Who are “their relatives”

The leaf footed bug, Leptoglossus phyllopus (L), is a relative of the stinkbug and feeds in the same way, has a similar lifecycle and causes similar damage. They are usually slightly larger and have “leaf like” appendages on their legs which are their namesake.

What is their lifecycle?

In Florida, overwintering adult stink bugs will place a clutch, or tight group of eggs, on a host plant early in the growing season. If their preferred plant is not available, they use a variety of weeds and grasses to lay eggs upon and provide food for their young. After eggs hatch, they go through several nymph stages before they finally reach the adult stage. Stink bugs have multiple generations in a year, often four to five. They readily move to find preferable food sources and might appear in a garden without warning to feed and cause destruction.

Nymph of the leaffooted bug, Leptoglossus phyllopus (L.). Photograph by Lyle J. Buss, University of Florida.

How are they best controlled?

First of all, many stink bugs use weeds as host plants to gather and feed upon, so controlling weedy plants around vegetable and fruit gardens might limit their numbers. If stink bugs are a major problem, planting trap crops, such as sunflowers, is beneficial. Stink bugs prefer to feed on sunflowers more than some other vegetables. This situation can be used to the gardener’s advantage by mechanically killing or spraying stink bugs on trap crops while avoiding treating food crops with pesticides. More information on trap cropping can be found here.

Additionally, stink bug traps are available. These mechanically trap stink bugs, thus reducing their numbers in the garden, but need to be monitored and serviced regularly. Several species of parasitic Tachinid flies are also predators of stink bugs. These flies lay their eggs on adult stink bugs. The fly larva use the bug as a buffet, slowly killing the bug.

Stink bugs are difficult to control with insecticides, but some measure of control can be achieved at their nymph stage with various approved fruit and vegetable insecticides containing pyrethrins. These products are readily available at local garden centers and feed & seed stores.

For more information, please check out the following resources:

by Larry Williams | Feb 11, 2021

Be careful when bringing firewood indoors. Photo credit: Larry Williams

Your firewood pile could be “bugged.” Many insects like to overwinter in wood. A wood pile is an ideal place for some insects to survive the winter. They don’t know that you intend to bring their winter home indoors during cold weather.

During colder weather, you can unknowingly bring in pests such as spiders, beetles and roaches when you bring in firewood. It’s best to bring in firewood only when you are ready to use it. Otherwise, those pests could become active and start crawling around inside your house. Many insects are potential problems indoors and there are usually control options once insects move into your home. However, preventing the insects from getting inside is the best approach.

If you store wood indoors for short periods of time, it is a good idea to clean the storage area after you have used the wood. Using a first-in, first-out guideline as much as possible will reduce chances of insect problems.

It’s best to keep your wood pile off the ground and away from the house. This will make it less inviting to insects and help the wood dry. It’s not difficult to keep the wood off the ground. The wood can be stacked on a base of wooden pallets, bricks or blocks, which will allow air movement under the wood. The wood can also be covered with a waterproof tarp or stored in a shed. Regardless of how it is stored, avoid spraying firewood with insecticides. When burned, insecticide treated wood may give off harmful fumes.

Some critters that live in firewood can be harmful to humans. To avoid a painful sting or bite from insects, spiders or scorpions (no Florida scorpion is considered poisonous, but they can inflict a painful sting), it is a good practice to wear gloves when picking up logs from a wood pile.

Firewood can be a good source of heat during our cold weather. If you’re careful with how you handle your firewood, hopefully it will warm you, not “bug” you.

by Pat Williams | Oct 21, 2020

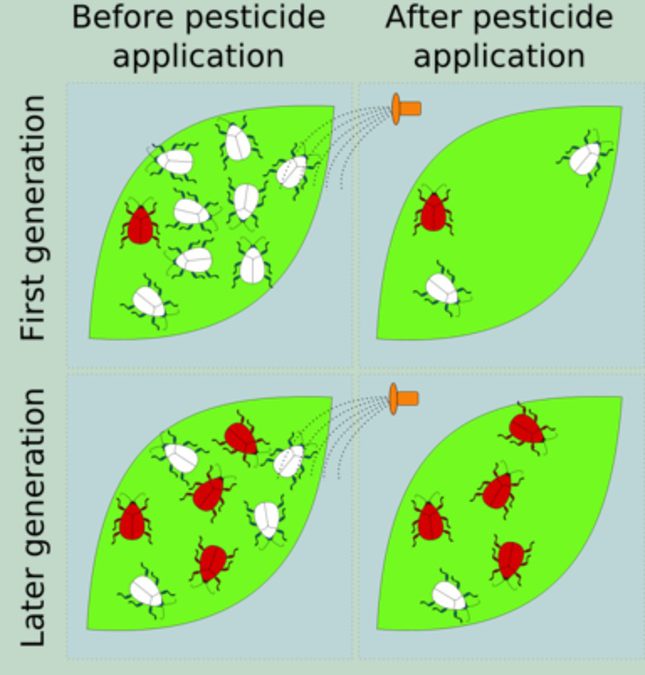

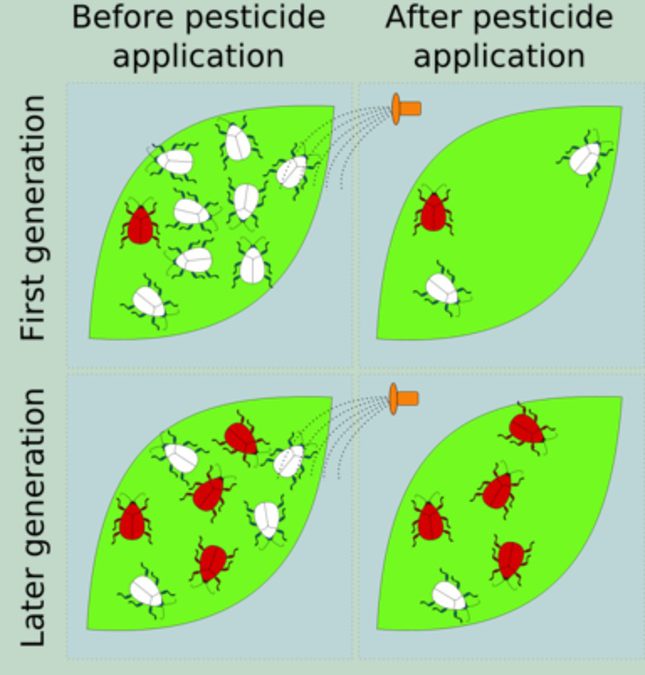

Normally, you will have one of four answers: “yes”, “no”, “I don’t know” or “what are super bugs?” The answer to the last one is an insect or other pest that has become resistant to chemical treatments through either natural selection (genetics) or an adaptive behavioral trait.

The next question is do you treat insect or pest problems at home with a purchased EPA registered chemical (one purchased from the nursery or other retailer)? If you answered yes, then the next question is how many times in a row do you apply the same chemical? If you only use one chemical until the product is used up, then you might be creating super bugs. Do you ever alternate chemicals and if you answer yes, do you understand chemical Modes of Action (how the pesticide kills the pest)? If you do not, then chances are the rotating chemicals might act in the same way. Thus, you are creating super bugs because in essence you are applying the same chemical with different labels.

Click on image for a larger view. Taken from https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/in714.

One of the first ways to reduce creating super bugs is to practice Integrated Pest Management (IPM). The very last step of an IPM philosophy is chemical control. You should choose the least toxic (chemical strength is categorized by signal words on the label: caution, warning, and danger) and most selective product. A chemical label advertising it kills many pests is an example of a non-selective chemical. You want to choose a chemical that kills your pest or only a few others. In Extension education, you will always hear the phrase “The label is the law.” To correctly purchase a chemical, you must first correctly identify the pest and secondly the plant you want to treat. If you need help from Extension for either of these, please contact us. Before purchasing the chemical, always read the whole label. You can find the label information online in larger print versus reading the small print on the container.

IRAC phone app.

You now have the correct chemical to treat your pest. Wear the recommended personal protective equipment (PPE) and apply according to directions. If your situation is normal, the problem is not completely solved after one treatment. You might apply a second or third time and yet you still have a pest problem. The diagram explains why you still have pests or more accurately super bugs.

Now the last question is how do we really solve the problem given that chemicals are still the only treatment option? A bit more work will greatly help the situation. You need to download the Insecticide Resistance Action Committee (IRAC) guide and find the active ingredient on your chemical label (http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pi121 or https://irac-online.org/modes-of-action/ and select the pdf). If you are like me, you can just download the IRAC MoA smartphone app and type in the active ingredient; otherwise, Appendix 5 in the pdf has a quick reference guide. Either way, you will know the Group and/or Subgroup. A lot of commonly purchased residential chemicals fall within 1A, 1B or 3. The successful treatment option is to select chemicals from different group numbers and use them in rotation. If you start practicing this simple strategy, your treatment should be more successful. Then when someone asks if you are creating super bugs, your answer will be no.

If you have any questions about rotating your chemical Modes of Action, please contact me or your local county Extension agent. For more resources on this topic, please read Managing Insecticide and Miticide Resistance in Florida Landscapes by Dr. Nicole Benda and Dr. Adam Dale (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/in714).

by Daniel J. Leonard | Oct 14, 2020

Article by Jessica Griesheimer & Dr. Xavier Martini, UF/IFAS North Florida Research and Education Center, Quincy

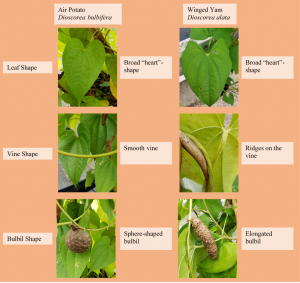

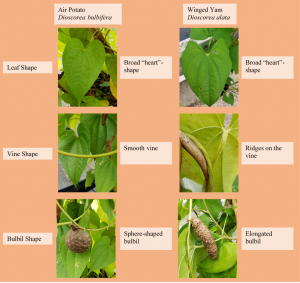

Dioscorea bulbifera, commonly known as the air potato is an invasive species plaguing the southeastern United States. The air potato is a vine plant that grows upward by clinging to other native plants and trees. It propagates with underground tubers and aerial bulbils which fall to the ground and grow a new plant. The aerial bulbils can be spread by moving the plant, causing the bulbils to drop to the ground and tubers can be spread by moving soil where an air potato plant grew prior. The air potato is commonly confused with and mistaken as being Dioscorea alata, the winged yam which is also highly invasive. The plants look very similar at first glance but have subtle differences. Both plants exhibit a “heart”-shaped leaf connected to vines. The vines of the winged yam have easily felt ridges, while the air potato vines are smooth. They also differ in their aerial bulbil shapes, the winged yam has a long, cylinder-shaped bulbil while the air potato aerial bulbil has a rounded, “potato” shape (Fig. 1).

In its native range of Asia and Africa, the air potato has a local biocontrol agent, Lilioceris cheni commonly known as the Chinese air potato beetle (Fig. 2). As an adult, this beetle feeds on older leaves and deposits eggs on younger leaves for the larvae to later feed on. Once the larvae have grown and fed, they drop the ground where they pupate to later emerge as adults, continuing the cycle. The Chinese air potato beetle will not feed on the winged yam, as it is not its host plant.Current methods of air potato plant, bulbil, and tuber removal can be expensive and hard to maintain. The plant is typically sprayed with herbicide or is pulled from the ground, the aerial bulbils are picked from the plant before they drop, and the underground tubers are dug up. The herbicides can disrupt native vegetation, allowing for the air potato to spread further should it survive. If the underground tuber or aerial bulbils are not completely removed, the plant will grow back.

The Chinese air potato beetle is currently being evaluated as a potential integrated pest management (IPM) organism to help mitigate the invasive air potato. The beetle feeds and reproduces solely on the air potato plant, making it a great IPM organism choice. During 2019, we studied the Chinese air potato beetle and its ability to find the air potato plant. It was found the beetles may be using olfactory cues to find the host plant. Further research is conducted at the NFREC to increase natural aggregation of the beetles on air potato to improve biological control of the weed.

Chinese Air Potato Leaf Beetle.

If you have the air potato plant, or suspect you have the air potato plant, contact your local UF/IFAS Extension Agents for help!