by Carrie Stevenson | Mar 17, 2015

A waterfront buffer zone may include a raised berm with native vegetation to slow runoff from a yard before entering the water. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson

A taste of spring weather has arrived, and people will soon be filling the home improvement stores and getting ready for outdoor projects. If you live on the water or near a storm drain, it’s worth considering buffer zones and best management practices for fertilizing and lawn maintenance.

A waterfront buffer zone is an area the length of one’s property line, typically running about 10 feet (although it can be wider) from the edge of a shoreline (or even a storm drain) into the yard. In this area, the homeowner allows native vegetation to grow along the water and uses low-maintenance plants within the buffer. In this zone, no fertilizers or pesticides are used. Some homeowners will build a small berm to divide the area of maintained lawn (uphill) from the downhill waterfront side. This berm may be composed of a mulched area with shrubbery to catch and filter runoff from the more highly maintained lawn. This combination of actions helps treat potentially polluted stormwater runoff before it reaches the water, and keeps homeowners from using chemicals close to the water. It is often quite difficult to grow turf next to the water, anyway, and this takes the pressure off of someone trying to grow the perfect lawn down to the water’s edge. The buffer zones are often quite attractive and can be an excellent transition between managed turf and the waterfront.

Unmaintained dirt roads along creeks are significant sources of sediment, which can harm the bottom-dwelling insects that form the base of the food web. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson

Erosion prevention is crucial along waterways, as well. An open, non-vegetated lot can contribute a significant amount of sediment to a storm drain, stormwater pond, or natural body of water. Whether grass, trees, or bushes, any kind of vegetation is preferable to soil washing out of a yard and into the water. Sediment is a problem because it causes water clarity to drop, which can prevent seagrasses from getting the sunlight they need. Once settled, underwater sediment can form a stifling layer that chokes out small insects and invertebrates, which live in the soil and form the basis of the aquatic food chain. With no fish food available, fish may die or move out of an area. The most dramatic examples of this can often be found at dirt roads that cross over creeks. If not managed properly, the clay on these roads can nearly bury a small stream.

Other lawn care techniques for protecting the waterfront and preventing stormwater pollution include not mowing along the water, using a deflector shield and staying 3’-10’ away from the water’s edge when fertilizing, and not allowing grass clippings to blow into storm drains. Large amounts of decaying grass in a waterway can use up available oxygen, endangering aquatic organisms. When applying granular fertilizer, be sure to sweep up any spills on concrete so it doesn’t run into a storm drain. When cutting grass, mow at the highest height recommended for your turf to encourage deep rooting and stress tolerance. Healthy turf is better able to withstand drought, pests, and choke out weeds, reducing the frequency of pesticide and water application.

by Les Harrison | Jan 22, 2015

Fallen leaves add much to the landscape. They feed the plants and many insect, retain water, and help stabilize the soil

For the homeowner who feels the need to rake leaves and pine needles, the task can be something of a minor nuisance. The showers of earth-toned leftovers appear suddenly and at inconvenient times, and their removal is never added to a chore list without dispute.

Disarray aside, these organic remnants provide far more benefits than problems. Their suburban untidiness becomes an insulating blanket which nurtures plants, animals, and insects with time released nutrients for use by the efficient and fortunate in the wild and those of us in civilization.

First and foremost, leaf litter is critical to the water holding capacity of the woodlands. The dried leaves, needles and twigs absorb and shade rainwater from the evaporative effects of the sun and wind.

When heavy rains inundate the soil causing flooding and runoff, it is the leaves that act as part of the natural delaying system to minimize the negative impact on streams, creeks and rivers. The delayed or halted runoff provides time for water to be absorbed by the soil and be filtered by the natural screening capacity of this organic material.

The moisture works in conjunction with native bacteria and fungus to convert the leaf litter into nutrients usable by plants and trees. While not as concentrated as commercial fertilizers, many of the same plant nutrients are present in the decaying leaf litter.

The decomposition is aided by a variety of insects and worms which nest in, eat and overwinter under the debris. The animal activity breaks up and stirs the elements along with inoculating microbes in the matter which speeds nutrient availability to plants and trees during ideal years.

Luckily, the region’s leaf drop is spread over months with the plants and trees responding to the solar cycle and weather. Autumn, winter and spring each bring defoliation of specific trees and plants.

During dry years the bug and bacteria activity slows in accumulated leaf litter, but the naturally occurring fire cycle continues the nutrient recycling under the tree canopies. The easy to burn material aides in controlling insects and plants that can aggressively overpopulate an area if unchecked.

Controlled burns also prevent destructive wildfires which are harmful to all north Florida residents. While these uncontrolled fires do deposit nutrients, they have many negative effects which far outweigh this single benefit.

January’s weather is part of a continuing natural succession which the native plants and trees incorporate to continue the wild beauty so common in the region. The current cold and rain will combine with the leaf drop to produce much growth in the next few months.

by Sheila Dunning | Aug 19, 2014

Pine bark beetles are frequent pests of stressed pines in the southern United States. The five most common southern pine bark beetle species include three in the genus Ips. Ips beetles usually colonize only those trees that are already stressed, declining, or fallen due to environmental factors. Infestations may occur in response to drought, root injury, disease, lightning strikes or other stresses including flooding.

Pine bark beetles are frequent pests of stressed pines in the southern United States. The five most common southern pine bark beetle species include three in the genus Ips. Ips beetles usually colonize only those trees that are already stressed, declining, or fallen due to environmental factors. Infestations may occur in response to drought, root injury, disease, lightning strikes or other stresses including flooding.

Ips calligraphus usually attacks the lower portions of stumps, trunks and large limbs greater than 4” in diameter. Early signs of attack include the accumulation of reddish-brown boring dust on the bark, nearby cobwebs or understory foliage. Ips calligraphus can complete their life cycles within 25 days during the summer and can produce eight generations per year in Florida. Newly-emerged adults can fly as far as four miles in their first dispersal to find a new host tree, whichever one is the most stressed.

Most trees are not well adapted to saturated soil conditions. With record rainfall this past April, the ground became inundated with water. When the root environment is dramatically changed by excess moisture, especially during the growing season, a tree’s entire physiology is altered, which may result in the death of the tree.

Water saturated soil reduces the supply of oxygen to tree roots, raises the pH of the soil, and changes the rate of decomposition of organic material; all of which weakens the tree, making it more susceptible to indirect damage from insects and diseases.When the ground becomes completely saturated, a tree’s metabolic processes begin to change very quickly. Photosynthesis is shut down within five hours; the tree is in starvation mode, living on stored starches and unable to make more food. Water moves into and occupies all available pore spaces that once held oxygen. Any remaining oxygen is utilized within three hours. The lack of oxygen prevents the normal decomposition of organic matter which leads to the production and accumulation of toxic gases such as carbon dioxide, methane, hydrogen sulfide and nitrogen oxide. Additionally, within seven days there is a noticeable root growth loss. Roots only develop when soil oxygen levels are at 5% -15%. Over time, the decaying roots are attacked by pathogens. The loss of root mass from decay and fungal attack leaves the tree prone to drought damage. After only two weeks of saturated soil conditions the root crown area can have so many problems that decline and even death are imminent.

When a tree experiences these anaerobic soil conditions it will exhibit symptoms of leaf loss with minimal to no new leaf formation. This usually appears two to eight weeks after the soil dries out again. Many trees will not survive, especially the more juvenile and mature trees. However, well established trees may still decline several years later, if they experience additional stresses such as drought or root disturbance from construction.

There is little that can be done to combat the damage caused by soil saturation. However, it is important to enable the tree to conserve its food supply by resisting pruning and to avoid fertilizing until the following growth season. Removal of mulch will aid in the availability of soil oxygen. Basically, it is a “wait and see” process. While water is essential to the survival of trees, it can also be a detriment when it is excessive, especially for drought tolerant pine species such as Sand Pine, which is prevalent throughout the coastal areas.

For urban and residential landscape trees, preventative strategies to avoid tree stress and therefore reduce the chances of infestation include the following:

1) avoiding compaction of, physical damage to, or pavement over the root zones of pines,

2) providing adequate spacing (15-20ft) between trees,

3) minimizing competing vegetation beneath pines,

4) maintaining proper soil nutrient and pH status and

5) limiting irrigation to established pine areas.

When infested trees are removed, care should be taken to avoid injury to surrounding pines, which could attract the more harmful pine bark beetle species Dendroctonus frontalis, the Southern Pine Bark beetle.

There is no effective way to save an individual tree once it has been successfully colonized by Ips beetles. In some cases, the application of an approved insecticide that coats the entire tree trunk may be warranted to protect high-value landscape trees prior to infestation. UF/IFAS Extension can assist with recommendations.

by Carrie Stevenson | Jun 23, 2014

Since the heavy flooding in late April of this year, many property owners have expressed concern to me and their local government officials about their neighborhood’s vulnerability to flooding. Homes and landscapes are most people’s largest investment, and the damage caused by a major storm can be financially and emotionally devastating.

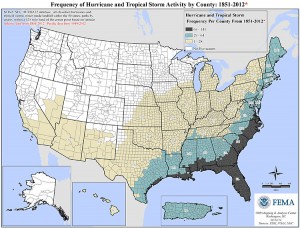

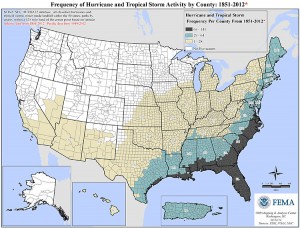

This map shows Florida’s extreme vulnerability to hurricanes and tropical storms, compared with the rest of the country. Graphics courtesy FEMA

To say that Florida is prone to flood is an understatement, at best. Between 1851 and 2012, every county in our state endured between 65 and 141 tropical storms and hurricanes. Many counties average one named storm every 1.1 years. While other states have coastal regions vulnerable to hurricanes, the entire state of Florida lies within FEMA’s highest designation of storm frequency. With hurricane season just beginning and record-breaking flood events in April, it is wise to consider flood insurance. Regular homeowners’ insurance policies do not cover damage related to flooding. Many homeowners go without flood insurance because their home is “high and dry” or “not in a flood zone.” It can be argued, however, that as a Floridian, particularly one in a region of the state with the highest annual average rainfall, you’re in a flood zone—it’s just a matter of whether you’re high or low risk. And, as we’ve seen recently, even those who thought they were low risk could be vulnerable.

Flood insurance is often very inexpensive for those outside of officially designated Special Flood Hazard Areas (think waterfront homes, low-lying property, creek floodplains, and barrier islands). Rates can be as low as $130/year for basic coverage in a low-risk area. It’s simple to get a ballpark figure for potential flood insurance costs by entering your address into a one-step “risk profile” online. According to the National Flood Insurance Program’s (NFIP) website, a quarter of NFIP flood insurance claims and third of Federal Disaster Assistance each year goes to residents outside a mapped high-risk flood zone . When the expenses related to flooding, including removal of flooring, walls, furniture, and damage to plumbing and wiring, are taken into consideration, flood insurance can be a smart investment.

Intense flooding can strike in unexpected locations during heavy rainstorms and tropical storms. This Pensacola street had never experienced serious flood damage prior to April 2014, so most residents did not have flood insurance. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson

Timing is important, too, because a 30-day waiting period is often required before flood insurance coverage kicks in. If you are also looking at additional windstorm insurance, be aware that policies will not be sold if a storm is in the Gulf. It is important to act sooner than later, but if you start now you can have flood and windstorm coverage in place before August and September. Our most severe storms historically occur during these months, after the Gulf has had all summer to warm up.

To purchase flood insurance, contact your local agent, find an agent online at www.floodsmart.gov, or call 1-888-379-9531. Be sure to ask exactly what is covered and under what circumstances, as there are many particularities to flood insurance. For up-to-date information on recent changes to the NFIP, please visit Coastal Planning Specialist Thomas Ruppert’s webpage.

Disclosure: The University of Florida/IFAS Extension program cannot make specific recommendations on insurance agents or providers. Please make the best decision for your home and family to prepare for storms and flooding.

by Sheila Dunning | Jun 17, 2014

The old cliché is “April showers bring May flowers”, but April deluges create weak plants and yellow grass. You were following the UF/IFAS recommendations and waited until April 15th to fertilize. You followed the Urban Turf Rule and applied a low-phosphate fertilizer with slow-release nitrogen. Yet, your grass is yellow and the shrubs haven’t put on any new growth. What happened? The 18” + of rainfall that we experienced at the end of April flushed nearly everything out of the soil, including any fertilizer you applied. Nitrogen and potassium are highly leachable. Phosphorus is also depleted under saturated soil conditions.

The old cliché is “April showers bring May flowers”, but April deluges create weak plants and yellow grass. You were following the UF/IFAS recommendations and waited until April 15th to fertilize. You followed the Urban Turf Rule and applied a low-phosphate fertilizer with slow-release nitrogen. Yet, your grass is yellow and the shrubs haven’t put on any new growth. What happened? The 18” + of rainfall that we experienced at the end of April flushed nearly everything out of the soil, including any fertilizer you applied. Nitrogen and potassium are highly leachable. Phosphorus is also depleted under saturated soil conditions.

If you haven’t submitted a soil test since the storm, now is the time to do so. It’s time to apply a summer fertilizer, but it needs to address all the nutrient deficiencies created from the excess rain. Soil test kits can be obtained from your County Extension office. When you get the results from the University of Florida Lab, it is important to remember the 4 Rs when applying fertilizer. It needs to be the Right Source, applied at the Right Rate, at the Right Time, and over the Right Place.

Best Management Practices (BMPs) have been developed to allow individuals to make conscientious decisions regarding fertilizer selection that will reduce the risk of water contamination. The Right Source for a BMP-compliant fertilizer is one that contains a portion of slow-release (water insoluble) nitrogen with little to no phosphorus, and a potassium level similar to the nitrogen percentage (e.g. 15-0-15, that contains 5% coated nitrogen). However, a soil test is the only way to accurately identify the specific nutrients your landscape is lacking. Many soil tests indicate a need for phosphate and currently it is illegal to apply more than 0.25 pounds per 1,000 sq. ft. without a soil test verifying the need.

Next, the fertilizer must be applied at the Right Rate. In order to do that, you must know the square footage of your property and how much you can spread using the settings on your equipment. Individuals walk at varied speeds and the product recommended rates are based on 1,000 sq.ft. areas. For information on calibrating application equipment refer to  the publication, “How to Calibrate Your Fertilizer Spreader”. Using the 15-0-15 fertilizer mentioned earlier, the Right Rate for one application would be 3 pounds per 1,000 sq.ft.. That 35 pound bag is all that is needed for a nearly 12,000 sq.ft. yard (a large corner lot).

the publication, “How to Calibrate Your Fertilizer Spreader”. Using the 15-0-15 fertilizer mentioned earlier, the Right Rate for one application would be 3 pounds per 1,000 sq.ft.. That 35 pound bag is all that is needed for a nearly 12,000 sq.ft. yard (a large corner lot).

The Right Time for applying fertilizer is when the plants are actively growing and beginning to show nutrient deficiencies. Summer, when rainfall and irrigation is frequent, is often a typical application time. The Right Place is only on living plant areas. Be cautious to avoid getting fertilizer on the sidewalk, driveway and street. A deflector on your spreader is very helpful. Otherwise, be sure to sweep or blow the fertilizer back onto the grass or into the landscape beds. Avoid having fertilizer end up in any water body.

by Carrie Stevenson | May 27, 2014

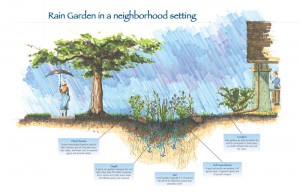

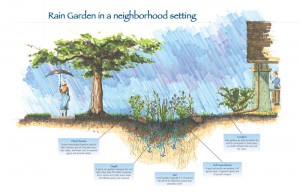

Rain gardens can make a beautiful addition to a home landscape. Photo courtesy UF IFAS

Northwest Florida experienced record-setting floods this spring, and many landscapes, roads, and buildings suffered serious damage due to the sheer force of water moving downhill. That being said, we are just entering our summer “rainy season,” so it may be wise to spend extra time thinking about how you want to landscape based on our typically heavy annual rainfall. For example, if you have an area in your yard where water always runs after a storm (even a mild one) and washes out your property, you may want to consider a rain garden for that spot.

Rain gardens work similarly to swales and stormwater retention ponds in that they are designed to temporarily hold rainwater and allow it to soak into the ground. However, they are quite different aesthetically, because they are planted with water-tolerant trees, shrubs, groundcovers and flowers to provide an attractive alternative to the eroding gully that once inhabited the area! Rain gardens are not “created wetlands,” but landscaped beds that can handle both wet and drier soil. Many of the plants best suited for rain gardens are also attractive to wildlife, adding another element of beauty to the landscape.

This diagram shows how a rain garden works in a home landscape. Photo courtesy NRCS

A perfect spot for a rain garden might be downhill from a rain gutter, areas notorious for excess water and erosion. To build a rain garden, the rainwater leaving a particular part of the property (or rooftop), is directed into a gently sloping, 4”-8” deep depression in the ground, the back and sides of which are supported by a berm of earth. The rain garden serves as a catch basin for the water and is usually shaped like a semi-circle. The width of the rain garden depends on the slope and particular site conditions in each yard. Within the area, native plants are placed into loose, sandy soil and mulched. Care should be taken to prevent the garden from having a very deep end where water pools, rather allowing water to spread evenly throughout the basin.

Besides reducing a problematic area of the lawn, a rain garden can play an important role in improving water quality. With increasing populations come more pavement, roads, and rooftops, which do almost nothing to absorb or treat stormwater, contributing to the problem. Vegetation and soil do a much better job at handling that water. Excess sediment, which can fill in streams and bays, and chemicals from fertilizers and pesticides are just some of the pollutants treated within a rain garden via the natural growth processes of the plants. Many commercial properties are considering rain gardens, also known as “bioretention” as more attractive alternatives to stormwater retention ponds.

The North Carolina Arboretum used a planted bioretention area to manage stormwater in their parking lot. Photo courtesy Carrie Stevenson

A handful of well-known perennial plants that work great in rain gardens include: Louisiana iris, cinnamon fern, buttonbush, Virginia willow, black-eyed Susan, swamp lily, tulip poplar, oakleaf hydrangea, wax myrtle, Florida azalea, river birch, holly, and Southern magnolia. For a complete list of rain garden plants appropriate for our area, visit the “Rain Garden” section of Tallahassee’s “Think about Personal Pollution” website, tappwater.org or contact your local Extension Office.