by Sheila Dunning | Dec 4, 2019

“Here we go ‘round the mulberry bush” is still sung by small children today. There are lots of different versions of the lyrics. But each usually describes a daily or weekly task list. In fact, the rhyme began in 1840 as a cadence for female prisoners exercising at the Wakefield Prison in England. There happened to be a Black Mulberry (Morus nigra) growing in the yard. Black Mulberry is a slow-growing short tree, so as a young tree it appears bushy.

Red Mulberry (Morus rubra) is the native Florida species. It tends to grow more upright, but is still a small tree. Additionally, there are White (Morus alba) and Pakistan (Morus macroura) , as well as, many hybrid Mulberries that will grow in the Florida panhandle. White Mulberry is a fast growing tall tree that is so aggressive that it is classified as an invasive species. It can rapidly seed natural areas and become the dominant species. But, the Pakistan Mulberry is a small tree that develops a characteristic crooked, gnarled trunk and a large fruit. It can be pruned as a bush easily.

Red Mulberry (Morus rubra) is the native Florida species. It tends to grow more upright, but is still a small tree. Additionally, there are White (Morus alba) and Pakistan (Morus macroura) , as well as, many hybrid Mulberries that will grow in the Florida panhandle. White Mulberry is a fast growing tall tree that is so aggressive that it is classified as an invasive species. It can rapidly seed natural areas and become the dominant species. But, the Pakistan Mulberry is a small tree that develops a characteristic crooked, gnarled trunk and a large fruit. It can be pruned as a bush easily.

Growing the mulberry bush can add a unique winter feature to the landscape while producing food for the birds. Yet, the plant is short enough that the fruit can be harvested without having to shake the tree and gather up the fruit from the ground before the birds get all the berries.

Mulberries are self-pollinating and only require about 400 chill hours. A chill hour is each hour that the temperature remain between 32 and 45 degrees Fahrenheit. After 400 cumulative hours the plant is able to flower. The fruit matures in the late spring to early summer. The birds will be sure to notify everyone when it’s time. Pakistan Mulberry can produce 4 inch long berries.

Mulberries will perform well if planted this winter. Plan on pruning them back each year if the bush effect is desired. It can take a year or two to get fully rooted. Don’t be surprised to see some fruit drop off prematurely as the tree/bush gets established. Also, pay attention to where the mulberry is installed. Windy spots will knock off fruit. What birds eat, they deposit. Mulberries will stain the surfaces they land on. If the fruit is walked through, the staining can be moved to indoor surfaces.

When picking fruit don’t forget the gloves unless dark stained fingers is the new look you’re trying to create.

For more information on mulberries: http://gardeningsolutions.ifas.ufl.edu/plants/trees-and-shrubs/trees/mulberry.html

by Carrie Stevenson | Nov 7, 2019

A female striped lynx spider protects her egg sac. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

With Halloween just behind us, some of us may still have fake spiders in our yards and cotton webbing all over the shrubbery. Spiders (along with bats) are among those creatures feared and demonized in folklore this time of year. It is important to remember, however, that both organisms are important predators and managers of our insect population.

Last week during a walk on the Extension property, I came across a large brown spider hovering protectively near her egg sac. Perched in a newly planted pine tree, I saw no obvious web. Instead, the spider loosely wrapped the pine’s needles with silk, forming a support structure for the relatively large egg sac.

Newly hatched striped lynx spiderlings on silk scaffolding covering a plant. Photograph by Laurel Lietzenmayer, University of Florida.

On further research, I learned that this female striped lynx spider (Oxyopes salticus) would have mated just once, after responding to a male’s courtship display (involving drumming and elaborate leg touches). She would have produced the egg sac 1-4 weeks after mating, attaching it to the pine needles, and will tend to it until her young emerge 20 days later. Up to five days after hatching, lynx spiderlings disperse by “ballooning” from the plant—they release a silk thread into the air, allowing the wind to carry them off like a tiny skydiver. Those spiderlings will mature into adults by 9 months, living their entire lifespan in just one year.

During that year, though, lynx spiders are important predators of pest insects. Instead of catching bugs in a web, they stalk their prey like a big cat—hence the name, “lynx.” They prey on many fly species, but also on bollworms and green stinkbugs that are major pests of cotton and soybean crops. These spiders are beneficial and highly vulnerable to insecticides.

by Les Harrison | Oct 8, 2019

Mushrooms growing on the roots of trees is a bad sign. This indicates the roots are decaying and the tree will soon become (or already is) unsafe.

On the doorstep of autumn, the weather is making its seasonal change in north Florida. It has been a bit cooler in the mornings, but the afternoons still qualify as hot.

What the winds of October will blow in is still anyone’s guess, but last year it was Hurricane Michael. Unfortunately, the storm’s brunt came in causing severe damage to homes, businesses and marine enterprises in several counties.

October is typically the month when tropical cyclone activity lessens in the Atlantic, but accelerates in the Gulf of Mexico. While beastly events like Hurricane Michael are relatively rare, it only takes one such incident to necessitate recovery efforts and expenses for years, if not decades.

The prudent course of action is to prepare for the worst while hoping for the best. One area of preparation where residents can have a distinctly positive effect is readying their trees for the potential assault.

Damage from falling trees and limbs is a major cause of destruction during tropical storms and hurricanes. Removing potential problems before the storm can minimize harm to structures and injury to residents.

Trees in decline are especially hazardous. Their compromised health makes them subject to uprooting and breakage with far less force than would effect a healthy tree.

There are several key indicators for tree health. Any single factor or a combination can mark a tree as unsafe.

Mushrooms growing on or very close to trees is a sign the tree is dying. The fungus is not the cause of decline, but only an indicator of the eventual fate.

Spores of the mushrooms are scattered by wind and water. Landing randomly, most arrive on a site devoid of necessary resources and never sprout.

Those lucky spores which land on decaying wood will likely sprout and take nourishment from the rotting plant material. Their roots accelerate the decomposition of the wood by consuming the available material and exposing more of the tree to colonization by mushrooms.

Sites on trees and plants infected with mushrooms typically are break points when pressure or stress is applied. If the mushrooms are located at the base of the tree, it is likely to be detached from its roots and topple over in heavy winds.

Another indicator of tree health is its crown, or the uppermost branches and leaves. Healthy trees and plants have full, green, and growing crowns.

When the crown turns brown and the leaves drop off, it is a good indicator the tree’s days are numbered. The causes may be disease, lightning, or mechanical interruption of the root system.

Lastly, bifurcation or trunk forking is a sign of a structurally weak tree. This condition may display itself when the tree emerges from the ground or at an elevated place on the mature tree trunk.

When the wind direction stresses the tree with enough force at its angle of vulnerability, a collapse results. Unfortunately, there is no simple way to tell how much wind is required to produce the failure.

Any tree with these problems should be evaluated by a certified arborist and removed when necessary. It may result in an expense now, but can save on expenses, inconvenience and aggravation if a storm randomly removes the tree in the future.

The question must be asked: Is it worth the gamble to wait on the winds of October?

To learn more about the tree health in north Florida, read the UF/IFAS publication HOW TREES GROW IN AN URBAN ENVIRONMENT.

by Julie McConnell | Jun 21, 2019

My obsession with plants started with the purchase of my first house in Waverly, Alabama in the late 90s. I bought a house with seven acres and of that about 1.5 acres was a fenced yard. The landscape was not very appealing, so I was on a mission to make it beautiful yet functional for my dogs. The only problem was, as a new homeowner, I had very little expendable income for my burgeoning plant habit. This dilemma forced me to be a resourceful gardener.

Shop the discount rack at garden centers

- Many retail garden centers (especially mixed use stores with limited plant space) will discount plants simply because they are no longer flowering. Plants look perfectly healthy but are just not considered “retail ready” anymore, so rather than hold them over until they bloom again and appeal to most shoppers the stores tend to mark them down.

- Plants are either growing or they are dead, so it is common to find some outgrowing their container and are getting “potbound” which means the root system is outgrowing the pot. Potbound plants are hard to keep watered without wilting and the solutions are to transition to a larger pot or plant in the ground. Most garden centers are not equipped to pot up overgrown plants to larger containers, so the easier solution is to sell them quickly. If you purchase a plant with circling roots be sure to trim the bottom and score (slice) the root ball to encourage roots to spread laterally.

- Avoid plants that appear diseased (leaf spots, brown stems, mushy parts, rotting odor) or have active feeding insect activity.

Compliment other gardeners’ plants

- When you get gardeners together, they inevitably start swapping plants. I really don’t have an explanation for this other that good old southern hospitality, but I’ve noticed over the years that when you express appreciation of plants to other people they tend to end up in your own yard. Ask if you can take a pinch (for cuttings) or offer to divide a clump of crowded perennials and you are on your way to a trunk full of plant babies.

- I can’t recommend this for multiple safety reasons, but I have been known to photographs plants in my travels then strike up a conversation with a homeowner who insisted I take one home.

Experiment with basic propagation techniques

- Grow flowers from seed. Either purchase seeds (usually under $2/pack) or collect seed heads from spent flowers in your own garden. After flowers fade, allow them to set seed then either crush and distribute in other parts of your garden or store in a cool, dry place until you can swap with friends.

- Division – clumping perennials such as daylilies, cast iron plant, iris or liriope can be dug up and cut into smaller pieces with a shovel or machete. You only need to be sure to have buds on top and roots on the bottom to make a new plant. Other plants create offshoots that can be removed from the parent plant. Examples of these are agave, cycads, and yucca.

- Cuttings – the list of plants that can be propagated from stem cuttings is endless but a few that are very easy are crape myrtle, hydrangea, and coleus.

- Patented plants can not be propagated.

For more information read Plant Propagation Techniques for the Florida Gardener or contact your local UF/IFAS Extension Office.

by Logan Boatwright | May 27, 2019

Everyone likes their privacy. Usually, a large eight-foot privacy fence is built for that reason. That option tends to be expensive. What is a different approach for a similar result? A natural wall!

One advantage of having a natural wall is that a homeowner has options when choosing plants. When it comes to choosing plants for a natural wall, the first thing to decide is if a wall needs to be year round or seasonal. Size would be the next factor to determine.

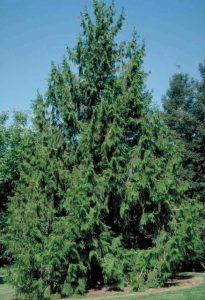

Japanese Cedar (Cryptomeria japonica) has the capability of growing 40 to 60 feet in height and 15 to 20 feet in width. There are some smaller varieties to pick from, but where is the fun in having a small wall?

Another plant option that would require pruning, but make an excellent natural wall is Japanese Yew (Podocarpus macrophyllus). This specimen will grow 30 to 40 feet tall and 20 to 25 feet in width if left unpruned, however, it is a slow grower. Yaupon Holly (Ilex vomitoria) comes in several selections of various sizes so the height range is 3 to 20 feet. The width range is 5 to 15 feet.

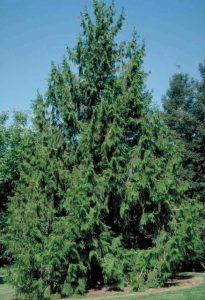

The Emerald Green Arborvitae is a fast grower that would be ideal for the homeowner who does not want a tall wall. It keeps a tight pyramid shape that will reach heights up 12 to 14 feet and needs 4 to 6 feet of space. Green Giant Arborvitae or Thuja Giant (Thuja standishii x plicata ‘Gre) is an excellent tree to pick for a natural wall. It has the capability to reach 50 to 60 feet in height and spreads out 12 to 20 feet at maturity. This arborvitae is considered to be a fast grower since it can increase more than 24” per year.

The larger selections of Loropetalum are other shrubs that homeowners have used to establish their privacy wall. One can expect a height up to 15 feet if left unpruned and pinkish to purple strap-like flowers, which makes for a great wall height.

‘Yoshino’ Japanese cryptomeria

Photo by Karen Russ, ©HGIC, Clemson Extension

A yaupon holly cultivar (Ilex vomitoria ‘Roundleaf’). John Ruter, University of Georgia, Bugwood.org Creative commons license.

Thuja plicata: Giant Arborvitae. Credit: Ed Gilman, UF/IFAS

Podocarpus macrophyllus or Japanese Yew. Credit: UF/IFAS

These plants are some of the selections homeowners may choose to start their natural walls. Given time, these shrubs will develop into a dense screen for the interruption of unwanted light or noise. To learn more about the aforementioned plant material, contact your local UF / IFAS extension agent.

by Carrie Stevenson | Apr 16, 2019

Historic live oaks provide shade and wildlife habitat at the Escambia Extension walking trail. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF / IFAS Extension

A recent study of 3-5 year olds found that the average pre-reading American child could identify hundreds of marketing brand logos (McDonald’s, Disney, even Toyota). Most researchers would be mightily challenged to find even a middle school student who can identify more than a couple of trees growing in their own backyard. The fields and forests many of us grew up in are steadily converting to look-alike suburban areas, so this lack of local natural knowledge is commonplace. As the quote by Senegalese forester Baba Dioum goes, “In the end, we will conserve only what we love; we will love only what we understand and we will understand only what we are taught.” If kids and adults do not appreciate and understand the natural world around them, we are unlikely to preserve these priceless wonders.

To do our part towards this aim of educating others, we at Escambia Extension received a grant from International Paper to plant 30 trees around our office’s walking track. Every tree has a clearly marked identification tag listing its common and botanical name.

A newly planted sassafras tree on the Extension walking trail. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF / IFAS Extension

Initially we just planned to add more shade trees to the sunny side of the track, but after a discussion with local foresters, we realized this effort could be an ideal teaching tool. The local middle and high school Future Farmers of America (FFA) chapters participate in a tree identification contest, and are tasked with knowing 50 native tree species. While 10 of them were tropical species that do not perform well in north Florida, we have the other 40 planted here on the property. Students and any interested citizen interested in learning these native species can walk along our track, getting exercise and taking in the natural world around them.

A spring walking event will kick off the official opening of the tree identification trail, so join us April 26 to learn more about healthy living and the value of trees. Or, join us for an Extension Open House on April 27 to explore the demonstration gardens, purchase vegetable plants, or learn more about Extension’s wide array of community services.

Red Mulberry (Morus rubra) is the native Florida species. It tends to grow more upright, but is still a small tree. Additionally, there are White (Morus alba) and Pakistan (Morus macroura) , as well as, many hybrid Mulberries that will grow in the Florida panhandle. White Mulberry is a fast growing tall tree that is so aggressive that it is classified as an invasive species. It can rapidly seed natural areas and become the dominant species. But, the Pakistan Mulberry is a small tree that develops a characteristic crooked, gnarled trunk and a large fruit. It can be pruned as a bush easily.

Red Mulberry (Morus rubra) is the native Florida species. It tends to grow more upright, but is still a small tree. Additionally, there are White (Morus alba) and Pakistan (Morus macroura) , as well as, many hybrid Mulberries that will grow in the Florida panhandle. White Mulberry is a fast growing tall tree that is so aggressive that it is classified as an invasive species. It can rapidly seed natural areas and become the dominant species. But, the Pakistan Mulberry is a small tree that develops a characteristic crooked, gnarled trunk and a large fruit. It can be pruned as a bush easily.