by Sheila Dunning | Apr 9, 2019

Call 811 before you dig. No one wants a weekend project to be the cause of Internet, phone and cable outages. Worse yet, what if someone gets hurt from contact with natural gas or electrical lines? That’s why it is so important to have buried utilities in the yard located and marked before digging. Sunshine 811 coordinates each individual company to clearly mark where the service lines are located. Homeowners are required by law to contact 811 three days before any soil removal is done. The service is free.

Call 811 before you dig. No one wants a weekend project to be the cause of Internet, phone and cable outages. Worse yet, what if someone gets hurt from contact with natural gas or electrical lines? That’s why it is so important to have buried utilities in the yard located and marked before digging. Sunshine 811 coordinates each individual company to clearly mark where the service lines are located. Homeowners are required by law to contact 811 three days before any soil removal is done. The service is free.

Have information prepared before making the request. Describe the work to be performed (e.g. fence install, landscaping, irrigation install), including the type of equipment that will be used. Specify the exact location on the property and how long the work will continue. Finally, provide all the contact information (e.g. name, phone number, e-mail), should there be any additional questions.

Call 811 or request a single address ticket online. Receive a ticket number and wait two full business days, not counting weekends or holidays. Then contact 811 again. Make sure that all the utilities have responded in the Positive Response System (PRS). Sometimes that may mean that the company doesn’t have anything to make in the area.

If there are utility lines running through the yard, they will be marked with specifically colored paints or flags. Red is used for electrical lines, orange indicates communication lines, yellow means gas, blue is used for potable water, purple is reclaimed water, and green indicates sewer lines. White lines may be used to outline digging areas and pink are temporary survey marks. This is the APWA Uniform Color Code.

Every effort is made to locate the lines as accurately as possible. But, the safest thing to do is hand dig to expose the utility line before using any mechanized equipment. Lines can vary up to 24” from the marked line and depths can be less than 5”. Remember there may be access lines running through the property even if that service isn’t utilized at that address.

Keep safe this spring. Call 811 before digging.

by Logan Boatwright | Mar 26, 2019

Hurricane Michael Damage – Photo Credit Larry Williams

The aftermath of Hurricane Michael has many homeowners preparing their landscapes for the upcoming season. Several have called the office in need of a home visit because they want ideas of what to replant with and how to kill the weeds that have popped up. One common question is, “What trees can I plant that are fast growing and has plenty of shade?” Before I answer their question, I ask them, “Are you planning for future storms or not?”

Trees that are considered ‘fast’ growing are not necessarily the best choice for future storms. Many of the fast growing trees can be easily uprooted, break easily in strong winds, are more prone to decay, and/or are rather short-lived (<50 years old). Additionally, a missing structural pruning plan for young and mature trees will increase the chances of fallen trees. Homeowners can expect to replant trees once again if these characteristics are likely. Keep in mind that no tree is absolutely wind-proof since other factors need to be ideal for wind-resistance. Trees like laurel oak (Quercus laurifolia), water oak (Quercus nigra), cherry laurel (Prunus caroliniana), bradford pear (Pyrus calleryana), and pecan (Carya illinoensis) are some to be cautious of when replanting for wind resistance.

A few tips for homeowners re-planting hurricane damaged trees:

- Plant trees with higher wind resistance in groups with adequate soil space and soil properties.

- Prevent damage to the roots.

- Have a variety of native species, ages, and layers of high-quality trees and shrubs.

- Some of the best trees a homeowner should consider replanting with could be live oak (Quercus virginiana), southern magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora), baldcypress (Taxodium distichum), river birch (Betula nigra), and Japanese maple (Acer palmatum). A more in-depth look at wind resistant trees can be found by reading Wind and Trees: Lessons Learned from Hurricanes.FOR 118

.

by Mary Salinas | Feb 26, 2019

You never know what you’ll find when you start looking closely in your garden. I was puzzled as to why there were three dead leaves hanging together on my sweetbay tree when all the other leaves looked so nice and healthy. On further investigation, I found a cocoon was made by binding the leaves together and it was firmly attached to the branch with silk.

The hanging dead leaves are a perfect hiding place for the cocoon of the sweetbay silkmoth. Photo credit: Mary Salinas.

This is the cocoon of the Sweetbay silkmoth, Callosamia securifera. Adult females lay their eggs on the native sweetbay tree, Magnolia virginiana, as the caterpillars only feed on sweetbay leaves. The trees tolerate having a few leaves eaten so there is no need to pick off the caterpillars if you find them. Local birds may do that for you as they rely on an abundance of caterpillars to feed their baby birds.

See photos of this beautiful moth with more details on its life cycle.

And then explore Gardening with Wildlife on UF/IFAS Gardening Solutions.

by Carrie Stevenson | Jan 7, 2019

The Chickasaw plum is covered in beautiful small white flowers in the spring. Photo credit: UF IFAS

The native Chickasaw plum is a beautiful smaller tree (12-20 ft mature height) that is perfect for front yards, small areas, and streetscapes. True to its name, the Chickasaw plum was historically an important food source to Native American tribes in the southeast, who cultivated the trees in settlements well before the arrival of Europeans. They typically harvested and then dried the fruit to preserve it. Botanist-explorer William Bartram noted the species during his travels through the southeast in the 1700’s. He rarely saw it in the forests, and hypothesized that it was brought over from west of the Mississippi River.

One of the first trees to bloom each spring, the Chickasaw plum’s white, fragrant flowers and delicious red fruit make it charmingly aesthetic and appealing to humans and wildlife alike. The plums taste great eaten fresh from the tree but can be processed into jelly or wine. Chickasaw plums serve as host plants for the red-spotted purple butterfly, and their fruit make them popular with other wildlife. These trees are fast growers and typically multi-trunked.

Almost any landscape works for the Chickasaw plum, as it can grow in full sun, partial sun, or partial shade, and tolerates a wide variety of soil types. The species is very drought tolerant and performs well in sandy soils.

The plum is in the rose family and has thorns, so it is wise to be aware of these if young children might play near the tree.

Winter is ideal tree-planting time in Florida. While national Arbor Day is in spring, Florida’s Arbor Day is the 3rd Friday of January due to our milder winters. This year, Escambia County’s tree giveaway will include Chickasaw plums, so if this tree sounds like a great addition to your landscape, come visit us on January 19 and pick one up.

For more information about tree selection in northwest Florida, contact your local county Extension office.

by Daniel J. Leonard | Nov 21, 2018

After a devastating windstorm, as we just experienced in the Panhandle with Hurricane Michael, people have a tendency to become unenamored with landscape trees. It is easy to see why when homes are halved by massive, broken pine trees; pecan trunks have split and splayed, covering entire lawns; wide-spreading elms were entirely uprooted, leaving a crater in the yard. However, in these times, I would caution you not to rush to judgement, cut and remove all trees from your landscape. On the contrary, I’d encourage you, once the cleanup is over and damaged trees rehabilitated or disposed of, to get out and replant your landscape with quality, wind-resistant trees.

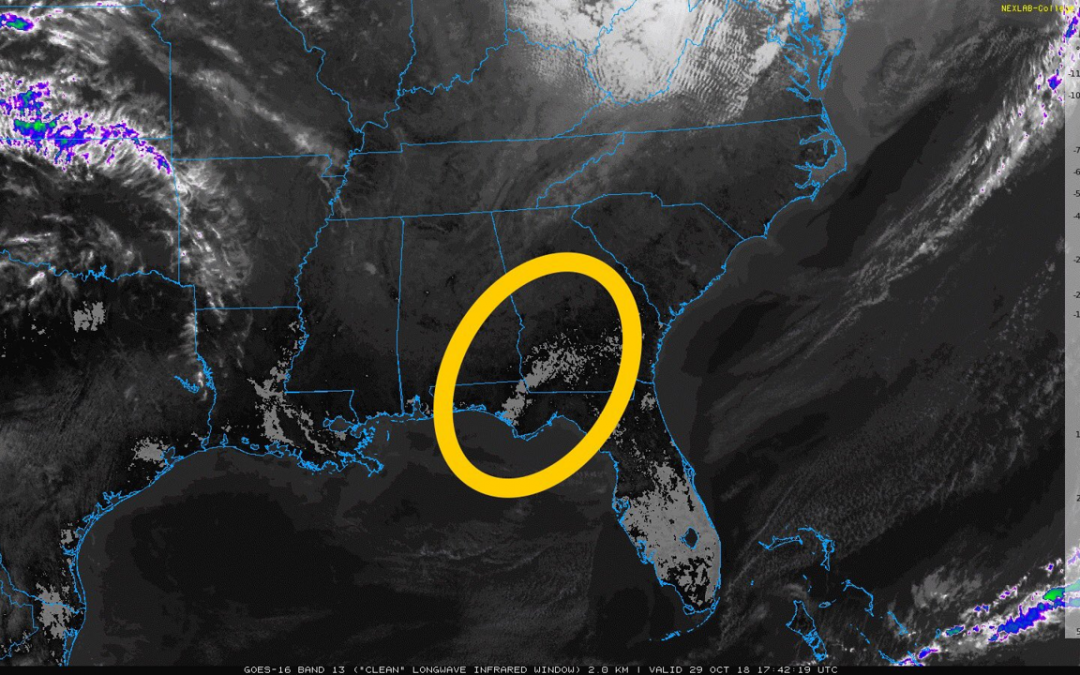

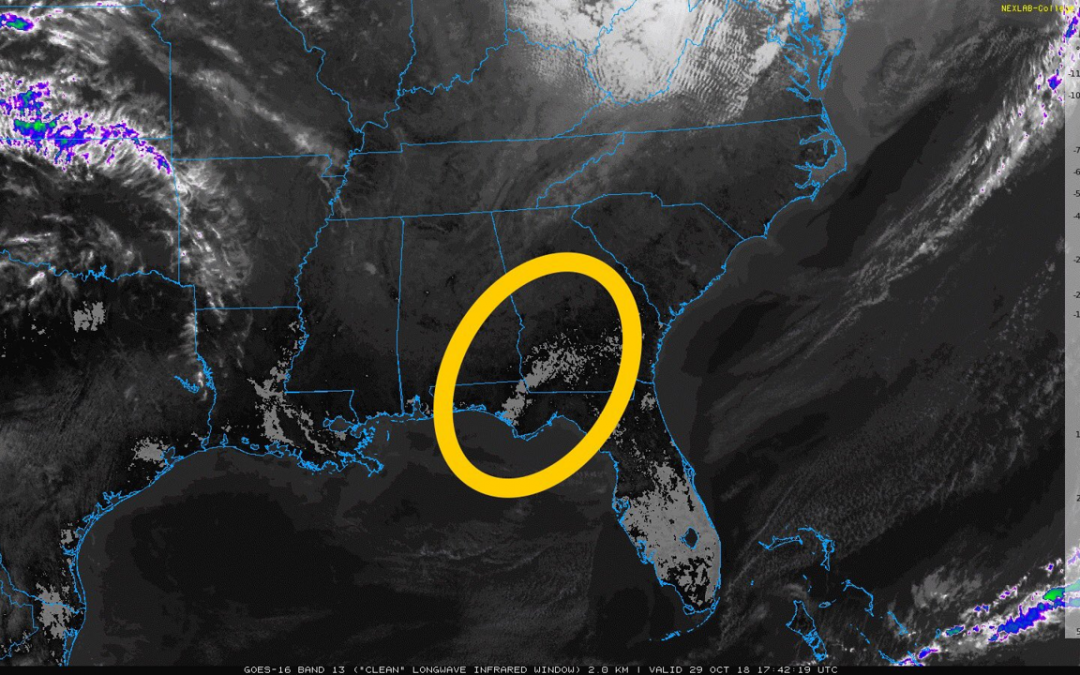

First, it’s helpful to take a step back and remember why we plant and enjoy trees and the important role they play in our lives. Beyond the commercial aspect of farmed timber, there are many reasons to be judicious with the chainsaw in the landscape and to plant anew where seemingly sturdy trees once stood. For example, trees provide enormous service to homes and landscapes, from massive cooling effects to aesthetic appeal. Take this thermal satellite image of Hurricane Michael’s path that simultaneously shows the devastation of a major hurricane and the role trees play in the environment.

Lightly shaded area showing higher ground temperatures from loss of vegetation.

In the lighter colored areas where the wind was strongest and catastrophic tree damage occurred, the ground temperatures are much higher than the unaffected areas. Lack of plant life is entirely to blame. Plants, especially trees, provide enormous shading effects on the ground that moderate ground temperatures and the process of transpiration releases water vapor, cooling the ambient air. Trees also lend natural beauty to neighborhood settings. There is a reason people termed the hardest hit areas by Michael “hellscapes”, “warzones”, etc. Those descriptions imply a lack of vegetation due to harsh conditions. In this respect, trees soften the landscape with their foliage colors and textures, create architecture with their height and shape, and screen people from noise, unpleasant sights and harsh heat.

Though all trees give us the benefits outlined above, research conducted by the University of Florida over a span of ten major hurricanes, from Andrew to Katrina, shows that some trees are far more resistant to wind than others and fare much better in hurricanes. In North Florida, the trees that most consistently survived hurricanes with the least amount of structural damage were Live Oaks, Cypresses, Crape Myrtle, American Holly, Southern Magnolia, Red Maple, Black Gum, Sycamore, Cabbage Palm and a smattering of small landscape trees like Dogwood, Fringe Tree, Persimmons, and Vitex. If one thinks about these trees’ growth habits, broad resistance to disease/decay, and native range, that they are storm survivors comes as no surprise. Consider Live Oak. This species originated along the coastal plain of the Southeastern United States and have endured hurricanes here for several millennia. Possessing unusually strong wood, they have also developed the ability to shed the majority of their leaves at the onset of storms. This defense mechanism leaves a bare appearance in the aftermath but allows the tree to mostly avoid the “umbrella” effect other wide crowned trees experience during storms and retain the ability to bounce back quickly. Consider another resistant species, Bald Cypress. In addition to having a strong, straight trunk and dense root system, the leaves of Bald Cypress are fine and featherlike. This leaf structure prevents wind from catching in the crown. Each of the other listed species possess similar unique features that allow them to survive hurricanes and recover much more quickly than other, less adapted species.

Laurel Oak split from weak branching structure.

However, many widely grown native trees and exotic species simply do not hold up well in tropical cyclones and other wind events. Pine species, despite being native to the Coastal South, are very susceptible to storm damage. The combination of high winds and beating rains loosens the soil around roots, adds tremendous water weight to the crown high off the ground, and puts the long, slender trunks under immense pressure. That combination proves deadly during a major hurricane as trees either uproot or break at weak points along the trunk. In addition to pines, other widely grown native species (such as Pecan, Laurel Oak and Water Oak) and exotic species (such as Chinese Elm) perform poorly in storms. Just as the trees that survive storms well possess similar features, so do these poor performers. We’ve already mentioned why pines and hurricanes don’t mix well. Pecan, Laurel Oak, and Water Oak tend to have weak branch angles and break up structurally in wind events. The broad spreading, heavy canopy of trees like Chinese Elm cause them to uproot and topple over. It would be advisable when replanting the landscape, to steer clear of these species or at least site them a good distance from important structures.

This piece is not a warning to condemn planting trees in the landscape; rather it is a template to guide you when selecting trees to replant. Many of our deepest memories involve trees, whether you first climbed one in your grandparent’s yard, fished under one around a farm pond, or carved your initials into one in the forest. Don’t become frustrated after a once in a lifetime storm and refuse to replant your landscape or your forest and deprive your children of those experiences. As sage investor Warren Buffett once wisely said, “Someone is sitting in the shade today because someone planted a tree a long time ago.”

For these and other recommendations about how to “hurricane-proof” your landscape, contact your local UF/IFAS Extension Office. Plant a tree today.

by Mark Tancig | Nov 8, 2018

Trees have a pretty bad reputation in north Florida these days. They’re on our homes, cars, streets, power lines, and all over the yard causing a lot of grief. While my heart goes out to all of those dealing with trees in places they shouldn’t be, now’s a good time to remember all the reasons we should want trees around. It’s also a good time to review how to minimize tree impacts from future storms.

An older, poorly branched loblolly pine in Tallahassee. Credit: Mark Tancig

Benefits of Trees

Beyond being a huge source of oxygen, necessary for many organisms to live, trees provide other benefits such as well. According to a recent analysis of Tallahassee’s urban trees, approximately three million pounds of pollutants, such as carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide, ozone, sulfur dioxide, and particulate matter, are reportedly removed each year. The same report calculated that half a billion gallons of precipitation was intercepted by these trees rather than becoming stormwater runoff, reducing impacts of erosion and non-point source pollution. These trees also saved citizens an estimated one million dollars. Total annual benefits to the citizens was over $15 million per year! Researchers have found that trees increase residential or commercial property values an average of 7%!

Ways to Minimize Tree Failure

Select Replacement Trees Wisely

While very few trees could make it through sustained winds of 155 mph, replanting trees sooner will help communities see the benefits mentioned above and help them return to their former beauty. Even the most wind-resistant trees are likely to fail in a storm like Hurricane Michael. UF/IFAS researchers have studied wind-thrown trees following hurricanes and have found these trees to be some of the most wind-resistant – hollies (Ilex spp.), southern magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora), live oak (Quercus virginiana), cypress (Taxodium spp.), cabbage palm (Sabal palmetto), and, interestingly, sparkleberry (Vaccinium arboreum).

The least wind-resistant trees include pecan (Carya illinoiensis), tulip poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera), laurelcherry (Prunus caroliniana), laurel oak (Quercus laurifolia), water oak (Quercus nigra), southern red oak (Quercus falcata), red cedar (Juniperus virginiana), pines (Pinus spp.), and Chinese elm (Ulmus parvifolia).

When replanting, consider planting at least three trees in a group rather than an individual tree, as researchers found that trees in groups fared better.

An older water or laurel oak. Credit: UF/IFAS.

Tree Care

With existing trees and newly planted trees, taking good care of the tree can help it withstand high winds. In addition to proper pruning techniques and providing adequate root zone space, paying close attention to minimize soil compaction and root zone disturbances will help create a stronger root system. Older trees should be regularly monitored for potential signs of decay.

An older oak with decay in trunk. Credit: UF/IFAS.

UF/IFAS has many great resources related to tree health and recovery after hurricanes. A search for Urban Forest Hurricane Recovery Program at our EDIS website (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu) has several publications to help decide how to move forward and create a healthy urban forest. Let’s not allow our frustration with the tree on the roof to prevent us from recognizing that trees are good.

Call 811 before you dig. No one wants a weekend project to be the cause of Internet, phone and cable outages. Worse yet, what if someone gets hurt from contact with natural gas or electrical lines? That’s why it is so important to have buried utilities in the yard located and marked before digging. Sunshine 811 coordinates each individual company to clearly mark where the service lines are located. Homeowners are required by law to contact 811 three days before any soil removal is done. The service is free.

Call 811 before you dig. No one wants a weekend project to be the cause of Internet, phone and cable outages. Worse yet, what if someone gets hurt from contact with natural gas or electrical lines? That’s why it is so important to have buried utilities in the yard located and marked before digging. Sunshine 811 coordinates each individual company to clearly mark where the service lines are located. Homeowners are required by law to contact 811 three days before any soil removal is done. The service is free.