by Gary Knox | Nov 25, 2014

View of the Discovery Garden in Gardens of the Big Bend.

Weeping false butterflybush, Rostrinucula dependens, is a new and unusual perennial being evaluated in Gardens of the Big Bend.

Gardens of the Big Bend is a new botanical and teaching garden located on the grounds of the University of Florida/IFAS North Florida Research and Education Center in Quincy. The goals of these gardens are to evaluate new plants, promote garden plants adapted to the region, demonstrate environmentally sound principles of landscaping and provide a beautiful and educational environment for students, visitors, gardeners and Green Industry professionals.Located just 10 miles south of the Georgia-Florida border in Florida’s “Big Bend,” the Gardens are in USDA Cold Hardiness Zone 8b and have sandy-clay soils more typical of continental conditions than those of peninsular Florida.

Gardens of the Big Bend is a series of gardens, each with a theme or plant focus:

- The Discovery Garden contains over 170 species or cultivars of new, improved or underutilized trees, shrubs and perennials. The garden’s purpose is to help gardeners, landscapers and nursery growers “discover” new plants.

- The Magnolia Garden is part of the National Collection of Magnolia in recognition of its’ more than 200 species and cultivars, including some of the rarest magnolias in the world.

- The Crapemyrtle Garden includes six species and over 100 cultivars.

- Conifers can be found throughout the Gardens but are featured in the new “Jurassic” garden. More than just pines and junipers, the Gardens contain over 50 conifer species and cultivars, many of which are rare. In recognition, the American Conifer Society has designated the Gardens as a “Conifer Reference Garden”, the only one in Florida, and the southernmost in the U.S.

- The Dry Garden is the newest addition and contains about 140 different types of agave, aloe, cactus, dyckia, sedum, yucca, bulbs and other dry-adapted plants. It consists of a south-facing berm of boulders, gravel and sand about 160 feet long, 35 feet wide and 6 feet tall.

- Other gardens feature native, shade, Southern heritage, and weeping plants as well as collections of Japanese hydrangea and shrub roses. Additional gardens will be installed as time and funding permit.

Parana pine, Araucaria angustifolia, is a rare type of conifer in the Gardens.

Gardens of the Big Bend formally began in 2008 thanks to the happy marriage of a new volunteer organization coupled with this University of Florida off-campus facility and plant collections I developed as part of research and extension projects. The volunteer organization, Gardening Friends of the Big Bend, Inc., formed in 2007 to support horticulture research and education. This group quickly seized on the idea of transplanting these existing plant collections into a series of gardens. Accordingly, its members hold fundraisers, provide volunteer labor and sponsor extension programs to raise awareness, provide funds and support garden development and maintenance.

Gardens of the Big Bend is located in Quincy at I-10 Exit 181, just 1/8 mile north on Pat Thomas Highway (SR 267). The gardens are free and open to the public during daylight hours year-round; professional staff are only available during normal business hours. To make a gift to the Gardens, please go to this website! Come visit us and watch the Gardens grow!

by Blake Thaxton | Nov 25, 2014

Photo Credit: Blake Thaxton

Often in Extension we are asked to look at unhealthy plants in the landscape. We see every problem under the sun. Whether it is diseases, insects, or cultural problems we run into them all. One problem that seems to be a trend, when clients show us a declining tree, is signs of improper tree installation. Though the tree may survive for 10 or 15 years after planting, it never thrives and it experiences a slow death. Here are 11 easy steps to follow for tree installation.

- Look Up

- Dig a shallow planting hole as wide as possible

- Find the point where the top-most root emerges from the trunk

- Slide the tree carefully into the planting hole

- Position the point where the top-most root emerges from the trunk slightly above the landscape soil surface

- Straighten the tree in the hole

- Remove synthetic materials from around trunk and root ball

- Slice a shovel down in to the backfill

- Cover the exposed sides of the root ball with mulch

- Stake the tree if necessary

- Come back to remove hardware

For more detailed information visit this UF/IFAS website.

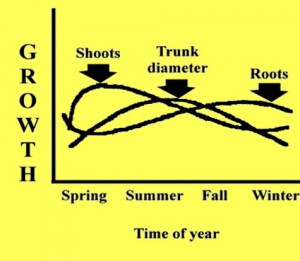

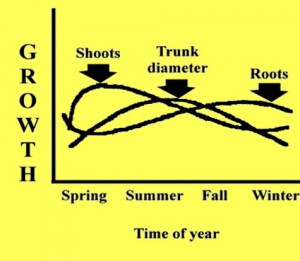

Also remember that fall is a great time to plant a tree because of the way trees grow. As you can see on the image above, roots tend to grow in the winter. This is a good thing so that the root system will be well established when spring comes and a new flush of growth will begin on the top of the tree.

by Taylor Vandiver | Nov 11, 2014

As winter approaches, short days and cool temperatures cause many plants to slow down and enter a suspended growth phase known as dormancy. Dormancy in plants is similar to the way bears hibernate during the winter. You may be asking yourself what is dormancy? And how can I get in on that? Well, to be honest, there isn’t an all-encompassing answer. It seems that plants (and bears) are keeping that secret all to themselves.

Fall foliage of Florida maple. Photo courtesy UF/IFAS.

Now that winter is indeed coming, deciduous plants start to breakdown proteins and other chemicals in their leaves and store them in the buds, bark and wood for growth next spring. Many deciduous plants lose their leaves as they become dormant, such as maples and dogwoods. Evergreen plants such as pine trees and camellias keep their leaves all winter.

There are actually two types of dormancy during the winter. One is called endo-dormancy. In endo-dormancy, the plant refuses to grow even under hospitable conditions. In endo-dormancy, something inside the plants is inhibiting growth. The other form is eco-dormancy and occurs when the plant is ready to grow, but the environmental conditions are not favorable (usually too cold). Short days and freezing temperatures in the fall induce endo-dormancy in the plant, which occurs first.

Shumard oak showing off its fall colors. Photo courtesy UF/IFAS.

As the plant enters endo-dormancy, it tracks chilling hours to chart the passage of the winter. Chilling hours are the time when temperatures drop below 45 degrees Fahrenheit. The number of hours required for chilling varies for different plants. Many people think the plant is tracking hours below freezing. However, hours below freezing have no effect on chilling, but will increase cold hardiness. If warm weather occurs before the plant completes its chilling requirement, no growth occurs. Chilling and endo-dormancy normally prevent plants from beginning growth during warm spells in the middle of the winter. Not all hours above freezing are equal. Temperatures between 35 and 45 degrees Fahrenheit seem to be most effective. Temperatures just above freezing and above 50 F are less effective and temperatures above 60 F often have a negative effect on chilling.

After a plant has checked off its chilling hours it is no longer in a state of endo-dormancy. It is now in eco-dormancy. The plants are dormant only because of cold temperatures. Warmer weather will cause plants to yawn, make that final stretch, and begin to grow. Growth first becomes apparent when buds swell and then green tissue emerges from the bud. However, plants actually begin growing before we notice their swelling buds. So this winter when your plants start to shed their leaves don’t be frightened, they may just be taking a much deserved rest in preparation for a brilliant show come spring.

Please contact your local extension office for more information.

by Carrie Stevenson | Nov 4, 2014

I recently met with a group of community volunteers who are interested in providing more butterfly habitat in our public areas. Monarchs migrating to Mexico this time of year use northwest Florida as a stopover and feeding site, but if host plants are unavailable they cannot sustain a healthy population. In addition, Gulf fritillaries, buckeyes, and swallowtails are spending time in local butterfly gardens, feeding on passion vine, butterfly bush, milkweed, and more.

The grassy area between this stormwater pond and woods is an ideal location for a butterfly garden. Willows growing along the edge attract butterflies already. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson

The volunteers and several county staff visited three publicly-managed stormwater ponds, which are an ideal setting for what some proponents term “Butterflyscaping.” The open space, water source, and diversity of plants along the edge of the ponds lend themselves well to wildlife habitat.

The permanently wet detention pond lined with cypress trees and sawgrass also provides habitat for fish, birds, and reptiles. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson

When considering adding vegetation to a neighborhood common area, there are several things to consider. First is maintenance. If there’s an annual contract with a landscaping company to mow or maintain an area, you’ll want to have a discussion about excluding the new planting area from mowing to establish new vegetation. You’ll also want to look at the soil and amount of sunlight to determine the best plant choices for the area.

A variety of groundcovers, flowering plants, shrubs and small trees will typically provide food for both caterpillars and adult butterflies. Once established, these new landscape additions will not only provide habitat and color, but may end up reducing maintenance costs as well.

For more information, the UF publication “Community Butterflyscaping” is an excellent resource for landscape design, plant choices, and practical steps toward getting started with a neighborhood or schoolyard project.

by Gary Knox | Oct 28, 2014

Figure 1. Paraná pine has a narrow, pyramidal form when young.

Paraná Pine, Araucaria angustifolia:

An ancient-looking conifer for modern landscapes

Paraná pine is a primitive-looking conifer valued for its unusual horizontal branching, sharply pointed triangular needles and neat, symmetrical form. The primitive appearance of this evergreen tree results from its resemblance to and relationship with an ancient group of conifers that dominated forests more than 65 million years ago.

Not a true pine, this dark green tree has a narrow, pyramidal shape when young. Paraná pine is considered fast-growing, and a tree planted at Gardens of the Big Bend in Quincy, Florida, reached a height of 30 feet and a width of 14 feet in eight years (Fig. 1).

Paraná pine reaches a mature size of 60 to 115 feet after 50 to 90 years or more in forests of southern Brazil. As it approaches maturity, the lower branches gradually die and the tree develops a dramatic dome shaped crown that somewhat resembles a candelabra due to upward pointing branch tips. Paraná pine is considered a large, long-lived tree. Fully mature trees may be 140 to 250 years of age, have heights up to 160 feet, and trunk diameters exceeding three feet (Fig. 2).

This evergreen conifer has distinctive sharp-pointed, tough, scale-like needles (Fig. 3). The dark green needles are triangular shaped and about 1 to 2.5 inches long. Needles tend to be tufted at outer ends of stiff, horizontally held branches. Needles persist for up to 15 years and cover all plant parts except the trunk and major branches. The stiff, sharp needles make the tree and branches difficult to handle, while also acting as a deterrent to deer feeding and other animal predation as well as foot traffic.

Figure 2. Closeup of the rough bark of Paraná pine.

Paraná pine is usually dioecious, meaning male and female flowers are borne on separate plants. Pollen cones are oblong, up to seven inches long and about one inch wide at the time of pollen release. Wind carries pollen to female plants bearing seed cones. Young female trees begin to set seed between 12 and 15 years of age. After pollination, seed cones mature about 18 to 36 months later, usually in fall. Seed cones are brown, globe shaped, 7 to 10 inches in diameter, and are usually found in the upper canopy of trees. Each cone holds about 100 to 150 two inch nut-like, narrowly winged seeds (Fig. 4). Cones fall when mature and break apart, dispersing seeds that germinate soon thereafter. Seeds are eaten by mammals and birds, thus also dispersing seeds.

This tree once covered vast areas of subtropical forests in southern Brazil and neighboring portions of Argentina and Paraguay. Native Americans gathered cones to harvest the seeds for food. European settlers recognized Paraná pine as an important timber tree and it was logged extensively through the 20th century. Paraná pine now is one of the rarest trees in Brazil and is considered critically endangered due to a declining population caused by habitat loss and exploitation. In recognition of the past importance of Paraná pine, this tree is the symbol for the Brazilian State of Paraná.

The seeds, locally called pinhões, are still a prized food in Brazil. The seeds are similar to large pine nuts and are eaten after roasting or cooking in salt water.

Figure 3. The triangular shaped needles of Paraná pine are stiff and extremely sharp.

Other common English names for Paraná pine are Brazilian pine and candelabra tree. Common Portuguese names for Araucaria angustifolia are pinheiro-do-Paraná, pinheiro, araucária, pinho, pinho Brasileiro, pinheiro Brasileiro, pinheiro são josé, pinheiro macaco, pinheiro caiová, pinheiro das missões, curi, and curiúva. Common Spanish names are pino blanco and pino de Missiones.

Despite the common names, Paraná pine is not a pine (Pinus spp.) and instead is related to the Monkey-puzzle tree (Araucaria araucana;), Bunya-bunya tree (Araucaria bidwillii;), and the Norfolk Island pine (Araucaria heterophylla;), commonly encountered in southern Florida.

Paraná pine is sometimes confused with China fir (Cunninghamia lanceolata;), another large conifer commonly encountered in old landscapes along the Gulf Coast and north Florida. China fir differs in having pointed needles, bright green coloring, and a broader, irregular pyramidal form.

Paraná pine prefers well drained, slightly acidic soil in sun or light shade. It grows best in a mild, warm temperate climate typical of USDA Cold Hardiness Zones 7-9, and can tolerate occasional severe freezes. Paraná pine transplants well: a tree at Gardens of the Big Bend (Quincy, FL) was moved by tree-spade after four years. Subsequent growth continued at the same rate as before moving. Pests and diseases have not been reported.

Seeds must be obtained fresh and are viable for only about six weeks. Typically, freshly harvested seeds are ordered from Brazil and planted soon after being received. Seeds germinate easily within three months of sowing (Fig. 5).

Figure 4. Seeds of Paraná pine are about two inches long.

As a “living fossil”, Paraná pine is prized for its unusual appearance, horizontal branching and dark green color. This evergreen conifer grows too large for most residential situations. Paraná pine is best used as an accent or conversation piece in arboreta, botanic gardens, parks, campuses, golf courses and other large-scale landscapes.

Figure 5. Although perishable, fresh seeds will germinate within three months of sowing.

by Eddie Powell | Oct 7, 2014

Fall color of Chinese tallow. Image credit UGA Extension

Chinese tallow tree (Sapium sebiferum (L.) a deciduous and very aggressive tree. Many people appreciate the fact that it grows fast, provides great shade, and has a beautiful reddish fall color.

Despite it’s attributes, it is highly invasive and considered a noxious weed. It has spread to every coastal state from North Carolina to Texas, and inland to Arkansas. In Florida it occurs as far south as Tampa. Chinese tallow was listed in Florida as a noxious weed in 1998 which means that possession with the intent to sell, transport, or plant is illegal in the State of Florida.

The Chinese tallow tree can reach heights of 30 feet and the seeds resemble popcorn, hence its other name, popcorn tree. These popcorn shaped seeds and the aggressive root system sprouts make it very hard to control the spread of this tree. Animals also spread the seeds freely!

Although the Chinese tallow has great fall color problems come with it.

Some questions to ask yourself:

- Do you want great fall color and a yard full of Chinese tallow?

- Hey what about the neighbor. Do they want Chinese tallow in their yard?

Think about more than fall when planting.

To read more on how to control Chinese tallow follow this link: edis.ifas.ufl.edu/FR251