by Carrie Stevenson | Jan 25, 2018

Ghost plant/Indian pipes emerging from the ground. Photo credit: Carol Lord, UF IFAS Extension

Imagine you are enjoying perfect fall weather on a hike with your family, when suddenly you come upon a ghost. Translucent white, small and creeping out of the ground behind a tree, you stop and look closer to figure out what it is you’ve just seen. In such an environment, the “ghost” you might come across is the perennial wildflower known as the ghost plant (Monotropa uniflora, also known as Indian pipe). Maybe it’s not the same spirit from the creepy story during last night’s campfire, but it’s quite unexpected, nonetheless. The plant is an unusual shade of white because it does not photosynthesize like most plants, and therefore does not create cholorophyll needed for green leaves.

In deeply shaded forests, a thick layer of fallen leaves, dead branches, and even decaying animals forms a thick mulch around tree bases. This humus layer is warm and holds moisture, creating the perfect environment for mushrooms and other fungi to grow. Because there is very little sunlight filtering down to the forest floor, the ghost flower plant adapted to this shady, wet environment by parasitizing the fungi growing in the woods. Ghost plants and their close relatives are known as mycotrophs (myco: fungus, troph: feeding).

Ghost plant in bloom at Naval Live Oaks reservation in Gulf Breeze, Florida. Photo credit: Shelley W. Johnson

These plants were once called saprophytes (sapro: rotten, phyte: plant), with the assumption that they fed directly on decaying matter in the same way as fungi. They even look like mushrooms when emerging from the soil. However, research has shown the relationship is much more complex. While many trees have symbiotic relationships with fungi living among their root systems, the mycotrophs actually capitalize on that relationship, tapping into in the flow of carbon between trees and fungi and taking their nutrients.

Mycotrophs grow throughout the United States except in the southwest and Rockies, although they are a somewhat rare find. The ghost plant is mostly a translucent shade of white, but has some pale pink and black spots. The flower points down when it emerges (looking like its “pipe” nickname) but opens up and releases seed as it matures. They are usually found in a cluster of several blooms.

The next time you explore the forests around you, look down—you just might see a ghost!

by Mary Salinas | Dec 14, 2017

Monarch butterflies. Photo credit: Pia-Riitta Klein.

We have grown to love monarch butterflies, with their striking orange and black markings and their fascinating annual migration from southern Canada 3,000 miles south to Mexico. To help them, we have increasingly planted milkweed, the only plant on which their caterpillars will feed. In northwest Florida, the milkweed species most planted has been tropical milkweed, Asclepias curassavica, as it is lush, showy and easy to grow.

Tropical milkweed, Asclepias curassavica, was visited by this monarch caterpillar who is now off to find a suitable place to make his transformation into a chrysalis. Photo by Mary Salinas, UF/IFAS Extension.

Tropical milkweed, unlike our native milkweeds that die back in late fall, will continue to grow through the winter unless killed by a hard freeze. Even if the cold kills the stems, it may regrow quickly from the roots. This seems like an advantage, but maybe not. The availability of a host plant for the caterpillars may be prompting adult females to stay and lay eggs rather than migrate south and be protected from deadly freezes.

Experts are also exploring links between the longer persistence of the tropical milkweed into winter and a build-up on those plants of a serious parasite Ophryocystis elektroscirrha, commonly referred to as OE.

So, what is the answer?

- Cut back any tropical milkweed to the ground at Thanksgiving. That may encourage female monarchs to migrate and prevent a deadly build-up of OE spores on the plants.

- Consider adding some native milkweed species to your butterfly garden. Here are some recommended species from Dr. Jaret Daniels:

- Aquatic Milkweed (Asclepias perennis)

- Swamp Milkweed (Asclepias incarnata)

- Pinewoods Milkweed (Asclepias humistrata)

- Redring Milkweed (Asclepias variegata)

Swamp Milkweed, Asclepias incarnata. Photo credit: Chris Evans, University of Illinois.

For more information:

Are non-native milkweeds killing monarch butterflies?

Monarch Joint Venture: Potential risks of growing exotic (non-native) milkweeds for monarchs

Monarch Butterfly, Danaus plexippus Linnaeus (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae: Danainae)

MonarchWatch.org

Gardening Solutions: Milkweed

by Mark Tancig | Oct 9, 2017

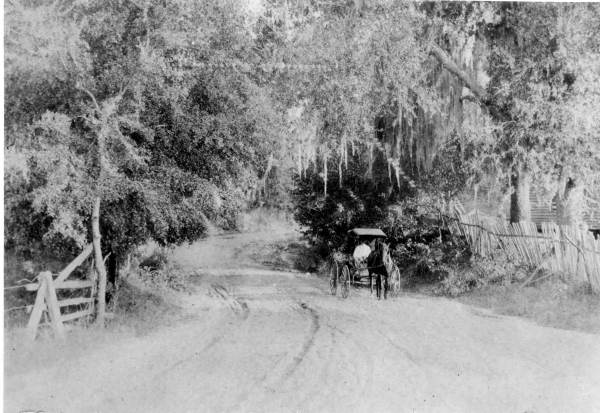

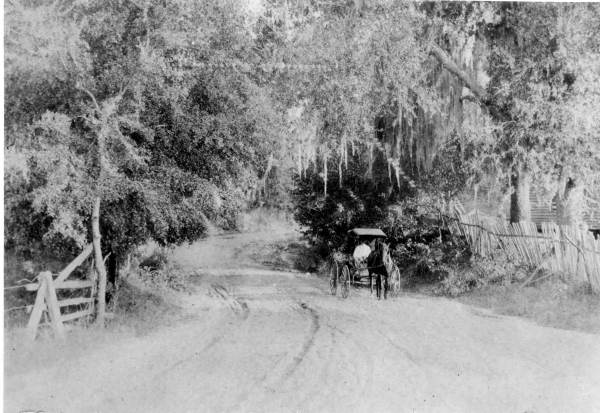

The network of backcountry roads winding through north Florida offer pleasant views of rolling pastures, fields of cotton, old tobacco barns, and, occasionally, a scenic overlook of our local “hills”. Many of these roads follow the original trails blazed by early settlers, or even Native Americans. Traveling along these small roads during the late summer and fall, drivers are also presented with an abundance of wildflowers along the road. It’s fun to imagine travelers of past generations being awarded the same colorful displays in days of yore.

Traveling a country road in 1905 when they were all country roads! Likely enjoying same roadside wildflowers. Credit: State Archives of Florida – Hays.

Some of the most common roadside wildflowers of late summer include Spanish needles (Bidens alba), goldenrod (Solidago spp.), silkgrass (Pityopsis spp.), slender scratchdaisy (Croptilon divaricatum), goldenaster (Chrysopsis spp.), and, one that the early settlers wouldn’t have seen, showy rattlebox (Crotalaria spectabilis), an invasive, exotic species that was introduced in the 1920’s.

Spanish needles. Credit: Brent Sellers – UF/IFAS.

Goldenrod. Credit: Larry Williams – UF/IFAS.

Silkgrass. Credit: JC Raulston Arboretum – NC State University.

Scratch daisy. Credit: Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants – UF/IFAS.

Showy rattlebox. Credit: Doug Mayo – UF/IFAS.

Many of these roadside wildflowers can also be found in home lawns and landscapes, usually in areas infrequently mowed, such as fence lines and field edges. Except for showy rattlebox, these roadside wildflowers are native species adapted to dry, disturbed sites, like roadsides. These native species provide ecosystem services to many native insects and other pollinators, including honey bees. Depending upon site particularities, allowing these plants to thrive in the residential landscape can provide similar ecosystem services and similar reward of color as is found along country back-roads.

While most folks would probably just consider these plants weeds, that determination depends upon an individual’s situation and each gardener’s opinion. In one yard, maybe it’s a weed, but along the roadside, it’s called a wildflower! Certainly, if left to set seed, these plants will spread. Mowing prior to seed maturity can help keep them in check while still getting a temporary show of color. Again, any showy rattlebox should be controlled since it is an invasive, exotic species that can invade natural Florida ecosystems and smother native plants. It’s also toxic to many animals if ingested.

North Florida’s roadside wildflowers are a pleasure see while cruising the back roads. If recognized and allowed to grow in residential landscapes, these plants can provide the same aesthetic and environmental benefits.

If you are interested in what’s growing in your yard, or local roadside, contact your county’s UF/IFAS Extension office.

by Sheila Dunning | Oct 2, 2017

Silkgrass Pityopsis spp. Picture by: Sheila Dunning

Each fall, nature puts on a brilliant show of color throughout the United States. As the temperatures drop, autumn encourages the “leaf peepers” to hit the road in search of the red-, yellow- and orange-colored leaves of the northern deciduous trees.

Here in the Florida Panhandle, fall color means wildflowers. As one drives the roads it’s nearly impossible to not see the bright yellows in the ditches and along the wood’s edge. Golden Asters (Chrysopsis spp.), Tickseeds (Coreopsis spp.), Silkgrasses (Pityopsis spp.), Sunflowers (Helianthus spp.) and Goldenrods (Solidago spp.) are displaying their petals of gold at every turn. These wildflowers are all members of the Aster family, one of the largest plant families in the world. For most, envisioning an Aster means a flower that looks like a daisy. While many are daisy-like in structure, others lack the petals and appear more like cascading sprays.

So if you are one of the many “hitting the road in search of fall color”, head to open areas. For wildflowers, that means rural locations with limited homes and businesses. Forested areas and non-grazed pastures typically have showy displays, especially when a spring burn was performed earlier in the year.

With the drought we experienced, moist, low-lying areas will naturally be the best areas to view the many golden wildflowers. Visit the Florida Wildflower Foundation website, www.flawildflowers.org/bloom.php, to see both what’s in bloom and the locations of the state’s prime viewing areas.

And if you are want to add native wildflowers and other Florida-friendly plants to your landscape join the Master Gardeners for their Fall Plant Sale to be held Saturday, October 14 from 8 am to noon at the Okaloosa County Extension Annex located at 127 SW Hollywood Blvd, Ft. Walton Beach.

by Sheila Dunning | Jun 22, 2017

Wildflowers near Live Oak, Florida. Image Credit, UF / IFAS

Unfortunately, reports from the National Research Council say that the long-term population trends for some North American pollinators are “demonstrably downward”.

Ten years ago the U.S. Senate unanimously approved and designated “National Pollinator Week” to help raise awareness. National Pollinator Week (June 19-25, 2017) is a time to celebrate pollinators and spread the word about what you can do to protect them. Habitat loss for pollinators due to human activity poses an immediate and frequently irreversible threat. Other factors responsible for population decreases include: invasive plant species, broad-spectrum pesticide use, disease, and weather.

So what can you do?

- Install “houses” for birds, bats, and bees.

- Avoid toxic, synthetic pesticides and only apply bio-rational products when pollinators aren’t active.

- Provide and maintain small shallow containers of water for wildlife.

- Create a pollinator-friendly garden.

- Plant native plants that provide nectar for pollinating insects.

There’s a new app for the last two.

The Bee Smart® Pollinator Gardener is your comprehensive guide to selecting plants for pollinators based on the geographical and ecological attributes of your location (your eco-region) just by entering your zip code. Filter your plants by what pollinators you want to attract, light and soil requirements, bloom color, and plant type. This is an excellent plant reference to attract bees, butterflies, hummingbirds, beetles, bats, and other pollinators to the garden, farm, school and every landscape.

The University of Florida also provides a low-cost app for Florida-Friendly Plant Selection at: https://fyn.ifas.ufl.edu/plants or go on-line to create a list of these same plants at: http://www.deactivated_site/

Not only can you find out which plants attract pollinators, you will be given the correct growing conditions so you can choose ‘the right plant for the right place’.

Remember, one out of every three mouthfuls of food we eat is made possible by pollinators.

by Mary Salinas | Jun 22, 2017

‘Mel’s Blue’ Stokes’ Aster. Photo credit: Mary Derrick, UF/IFAS Extension.

Florida is home to some of the most beautiful flowering perennials. An exceptional one for the panhandle landscape is Stokes’ aster (Stokesia laevis) as it is showy, deer resistant and easy to care for. Unlike other perennials, it generally is evergreen in our region so it provides interest all year.

Upright habit and profuse blooming of ‘Mel’s Blue’ Stokes’ Aster. Photo credit: Mary Derrick, UF/IFAS Extension.

The original species of Stokes’ aster has purplish-blue flowers but cultivars have been developed with flowers in shades of white, yellow, rosy-pink and a deep blue. The flowers are large, eye-catching beauties that bloom in spring and summer. They also last well as a cut flower. You will find that bees and butterflies will appreciate their nectar! Remove spent flowers after blooms have faded in order to encourage repeat flowering.

A location in your landscape that provides part sun with well-drained rich soil is best for this perennial. Stokes’ aster is native to moist sites so it does best with regular moisture.

Stokes’ aster attracts butterflies like this black swallowtail. Photo credit: Mary Derrick, UF/IFAS Extension.

As with many perennials, the plant will form a large clump after a few years; this gives you the opportunity to divide the clump in the fall and spread it out in your landscape or share the joy with your gardening buddies.

For more information:

Gardening with Perennials in Florida