by Evan Anderson | Sep 16, 2021

Here in Florida, we have snakes. Some may say we have lots of snakes. While their presence may be something to be expected out in wild areas, homeowners often find it alarming when these creatures show up near places where we live. The reaction is often a simple one: if it is a snake, kill it.

Dealing with snakes should not be like this, however. Although some are venomous, many others are harmless to humans and make valuable contributions to the local ecology. As more natural areas become developed, wildlife such as snakes are increasingly pushed into close contact with people, so learning to live with them is important.

Of the 46 species of snakes found in Florida, only 6 are venomous. The chances of being bitten by one of these venomous snakes is very low; there are only 7,000-8,000 bites in the entire U.S. each year. Fatalities are even more rare, with less than ten people typically dying across the country annually from venomous snakebites. In a country with a population of around 330 million, that’s not a lot.

A venomous Eastern diamond-backed rattlesnake.

Snakes, especially venomous ones, should be treated with respect, however. Knowing how to identify a snake can be an important step in knowing how to react to them, and understanding their behavior can help avoid unfortunate encounters. The venomous snakes we have in Florida are the copperhead, the coral snake, the cottonmouth or water moccasin, the Eastern diamond-backed rattlesnake, the pygmy rattlesnake, and the timber rattlesnake. For help in identifying these species, see our guide on EDIS at https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/UW229.

A harmless hognose rattlesnake.

Understanding snake behavior, including their feeding habits and preferred habitats, is also important. If you can make the areas you live in less hospitable to snakes, especially venomous ones, they’ll be less likely to move in. This doesn’t mean getting rid of every snake out there – some snakes that are harmless to humans may be predators that consume other snakes (including venomous ones) or rodents. Because venomous snakes often consume rodents and other small animals, allowing the nonvenomous ones to control populations of prey can help keep dangerous snakes out!

Watch out for areas where snakes may shelter, including tall grass, overgrown shrubs, piles of brush and wood, or debris. There is no need to remove all such things from a property, as other wildlife use them as well, but keep them away from houses and areas where people frequent. Also be sure to keep rodents under control in and around buildings to avoid attracting snakes that feed on them. You can find more information on managing habitat to deal with snakes at https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/UW260.

by Beth Bolles | Aug 18, 2021

In a garden with a variety of flowers, pollinators will be abundant. Sometimes we don’t always recognize the specific pollinator when we see it, but there are some native pollinators that leave other signs of their activity. One of our medium-sized native bees will leave a distinctive calling card of recent activity in our landscape.

Leafcutter bees have collected circular notches from the edges of a redbud tree. Photo by Beth Bolles, UF IFAS Extension Escambia County.

If you see some of the leaves of trees and shrubs with distinct circular notches on the edges of the leaves, you can be sure the Leafcutter bee is present. The females collect the leaf pieces to make a small, cigar-shaped nest that may be found in natural cavities, such as rooting wood, soil, or in plant stems. Each nest will have several sections in which the female places a ball of pollen and an egg. The emerging larvae then have a plentiful food source in order to develop into an adult bee.

When identifying a leafcutter bee in your landscape, look for a more robust bee with dark and light stripes on the abdomen. These bees also have a hairy underside to their abdomen where they carry the pollen. When loaded with pollen their underside will look yellow.

Leafcutter bees are solitary bees that are not considered aggressive. A sting would only be likely if the bee is handled. Your landscape will have many plants that a leafcutter may use for nesting material. The pollinating benefits of these bees far outweigh any cosmetic injury to the plant leaf margins.

Leafcutter bees are solitary bees that are not considered aggressive. A sting would only be likely if the bee is handled. Your landscape will have many plants that a leafcutter may use for nesting material. The pollinating benefits of these bees far outweigh any cosmetic injury to the plant leaf margins.

Visit Featured Creatures to see a photo of the leaf pieces made into a nest.

by Sheila Dunning | Jul 15, 2021

Photo by Dr. Steve Johnson

Treefrog calls are often heard with each rain event. But, how about a “snoring raspy” call that begins after a day time light rain? That may be a male Cuban treefrog trying to attract the girls. Cuban treefrogs breed predominately in the spring and summer. Reproduction is largely stimulated by rainfall, especially warm summer rains such as those associated with tropical weather systems and intense thunderstorms.

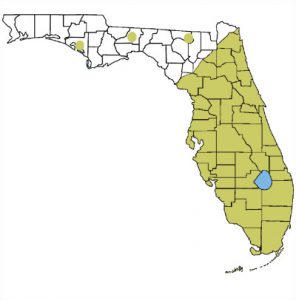

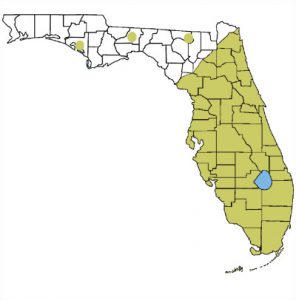

Range of Cuban treefrogs

The Cuban treefrog, Osteopilus septentrionalis, was accidently introduced to Florida in the 1920’s as a stowaway in shipping crates from the Caribbean. Over the last hundred years, the invasive frog has managed to spread throughout Florida and the Southeastern U.S. by hitchhiking on ornamental plants, motorized vehicles, and boats. Though occasional cold winters have created temporary population setbacks, new generations of Cuban treefrogs continue to be reported in north Florida, including the Panhandle.

An invasive species is generally defined as a plant, animal or microbe that is found outside of its native range, where it negatively impacts the ecology, economy or quality of human life. Cuban treefrogs come out at night to feed on snails, millipedes, spiders and a vast array of insects. But, they are also predators of several Florida native frogs, lizards and snakes. Tadpoles of the invasive Cuban treefrog have been shown to inhibit the growth and development of native Southern toad and green treefrog tadpoles when all of the species are in the same water body. Additionally, a large female Cuban treefrog can lay over 10,000 eggs per season in very small amounts of water.

Panhandle citizens can help manage the invasive Cuban treefrog by learning to identify them and reduce their numbers. All treefrogs have expanded pads on the ends of their toes. Cuban treefrogs have exceptionally large toepads. They also have a “big eyed” appearance due to their oversized bulging eyes. Cuban treefrogs may exceed 6 inches in length, have warty-looking skin with possible blotches, bands or stripes, and vary greatly in color. However, they can be distinguished from other treefrogs. Cuban treefrogs have a yellowish wash where their front and rear legs are attached to their body. Juvenile Cuban treefrogs have red eyes and blue bones visible through the skin of their hind legs. The skin of the Cuban treefrog produces a sticky secretion that can cause a burning or itching sensation if it contacts the eyes or nose of certain individuals. It is recommended to wear gloves and wash your hands after handling Cuban treefrogs.

Panhandle citizens can help manage the invasive Cuban treefrog by learning to identify them and reduce their numbers. All treefrogs have expanded pads on the ends of their toes. Cuban treefrogs have exceptionally large toepads. They also have a “big eyed” appearance due to their oversized bulging eyes. Cuban treefrogs may exceed 6 inches in length, have warty-looking skin with possible blotches, bands or stripes, and vary greatly in color. However, they can be distinguished from other treefrogs. Cuban treefrogs have a yellowish wash where their front and rear legs are attached to their body. Juvenile Cuban treefrogs have red eyes and blue bones visible through the skin of their hind legs. The skin of the Cuban treefrog produces a sticky secretion that can cause a burning or itching sensation if it contacts the eyes or nose of certain individuals. It is recommended to wear gloves and wash your hands after handling Cuban treefrogs.

It is important to document the locations of Cuban treefrogs in the Panhandle. By placing short sections of PVC pipe in the ground around your home and garden will provide hiding places for treefrogs that enables you to monitor for Cuban treefrogs. Cut 10 foot sections of 1.5-inch-diameter PVC pipe into approximately three-foot-long sections and push them into the ground about 3-4 inches. To remove a frog from a pipe, place a clear sandwich bag over the top end, pull the pipe from the ground, and insert a dowel rod in the other end to scare the frog into the baggie. If you suspect you have seen one, take a picture and send it to Dr. Steve Johnson at tadpole@ufl.edu. Include your name, date, and location. Dr. Johnson can verify the identity. If it is a Cuban treefrog, upload the information by going to http://www.eddmaps.org/ and click the “Report Sightings” tab.

Once identified as a Cuban treefrog, it should be euthanized humanly. To do that, the Cuban treefrog in a plastic sandwich bag can be placed into the refrigerator for 3-4 hours then transferred to the freezer for an additional 24 hours. Alternatively, a 1-inch stripe benzocaine-containing ointment (like Orajel) to the frog’s back to chemically anesthetize it before placing it into a freezer. After freezing, remove the bagged frog from the freezer and dispose of in the trash. Ornamental ponds should also be monitored for Cuban treefrog egg masses especially after a heavy rain. The morning after a rain, use a small-mesh aquarium net to scoop out masses of eggs floating on the surface of the pond and simply discard them on the ground to dry out. Various objects that can collect water found throughout your yard need to be dumped out regularly to reduce breeding spots for both Cuban treefrogs and mosquitoes.

by Evan Anderson | May 20, 2021

Lawns and landscapes are greening up this time of year, and it’s not just plants showing signs of activity. All sorts of creatures are out there living their lives, and some of them are doing some digging.

From little piles of dirt to big mounds and long tunnels, it can be frustrating to figure out what is disrupting your carefully tended lawn or ornamental bed. Luckily, there are differences between the possible culprits. Here are some of the possibilities (see the associated links for more information and control methods):

-

A miner bee hole. Photo: Evan Anderson

Miner Bees (and other ground nesting bees and insects) – Miner bees are harmless, solitary bees that tunnel into the soil. Not to be mistaken for yellowjackets, each bee digs her own small nest to lay her eggs in. Multiple such bees may be attracted to the same location, but they do not form hives and aren’t aggressive. Small mounds of soil may form around the entrances to their nests, but these will vanish after a rain.

- Moles – Small mammals (not rodents) that produce raised tunnels along the surface of the ground. They forage for insects among the roots of plants, and while their presence does have some benefits, many homeowners dislike their aesthetic contributions to the landscape. If you can overlook their tunnels, they do help aerate soil and eat pests like mole crickets, grubs, ant larvae, caterpillars, and slugs.

- Pocket Gophers – Sometimes called “sandymounders” or “salamanders” by old-timers, these are small rodents that dig tunnels beneath the ground. Active especially in cooler months, they make a series of mounds of soil in a line along their tunnel as they excavate. They feed on roots, bulbs, and tubers, though their sand-mounding is often more a problem than their feeding.

-

A fire ant mound in the landscape. Photo: B. Drees

Fire Ants – A single ant isn’t particularly threatening, but fire ants have found that thousands of rage-filled friends make a good deterrent. They build large mounds of soil to help regulate temperature and moisture in their nests, which can be quite unsightly in the landscape. Disturbing these mounds will unleash hordes of stinging ants, so beware; while they don’t necessarily do any harm to plants, they aren’t terribly friendly neighbors.

- Squirrels -These tree-dwelling rodents may nest up in the boughs, but often come down to the ground to look for food. In doing so, they may dig small holes as they forage for nuts, seeds, and fungi. The holes they dig are typically shallow and usually not too much of a problem.

- Armadillos – Nocturnal and heavily armored, the armadillo forages for insects in the ground. While it may sound beneficial to have an animal removing all the pest insects around, they aren’t careful about the damage they do while they feed. A hungry armadillo can dig numerous 3-5 inch wide, 1-3 inch deep holes in a lawn overnight, and may also burrow under structures, driveways, and patios.

- Yellowjackets – Yellowjackets are a bit of an honorable mention for this list, due to the fact that their digging often goes unseen. These ground-dwelling hornets leave no mounds or raised tunnels to identify their nests by. Instead, a small hole is often the only indication they are present, until a person or pet disturbs them. Then…surprise! It’s time for stinging, screaming, and crying.

For animal pests, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission maintains a list of nuisance wildlife trappers at https://public.myfwc.com/HGM/NWT/NWTSearch.aspx. For insects, you may need to contact a local pest control specialist or company. For help in identifying a problem, contact your local Extension office.

by Molly Jameson | Oct 28, 2020

The Carolina wolf spider (Hogna Corolinensis) is the largest wolf spider, measuring up to 22-35 mm. It is the state spider of South Carolina, the only state that recognizes a spider as a state symbol. Photo by Eugene E. Nelson, Bugwood.org.

Halloween coincides with a full moon this year, so you may want to be on the lookout for hungry werewolves. In your garden, you may also be on the lookout for a much smaller, yet just as frightful, type of wolf. Well – wolf spider, that is!

But have no fear, just as the little werewolves of the neighborhood will be sated by a handful of sweets, a wolf spider will be satisfied once it finds its meal of choice. Wolf spiders are predators, feeding primarily on insects and other spiders. Much like a werewolf, wolf spiders prefer to stalk their prey at night. This is good news for gardeners – as it means you’ll have an insect hunter working for you while you sleep.

Wolf spiders are in the family Lycosidae, and there are over 2,000 species within this family. Lycos means “wolf” in Greek, inspired by the way wolves stalk their prey. Although, unlike wolves who hunt in packs, wolf spiders are very much solitary. These spiders do not spin webs; instead, they keep to the ground, where they can blend in with leaf litter on the soil floor. Some wolf spiders even dig tunnels, or use tunnels dug by other animals, to hide and hunt.

Although most spiders have poor eyesight, wolf spiders have excellent vision, which they use to spot prey. Photo by James O. Howell, University of Georgia, Bugwood.org.

Wolf spiders have eight eyes that are arranged in three rows. This includes four small eyes in the lowest row, two very large eyes in the middle, and two medium-sized eyes off to either side on top. Some of their eyes even have reflective lenses that seem to sparkle in the moonlight. Using their excellent eyesight and sensitivity to vibrations, they stealthily stalk prey such as ants, grasshoppers, crickets, and other spider species. Female wolf spiders, which are bigger than males, may even take down the occasional lizard or frog.

No matter the meal, many wolf spiders pounce on their prey, hold it between their eight legs, and roll with it onto their backs, creating a trap. They then sink their powerful fangs, which are normally retracted inside the jaw, into the victim. The fangs have a small hole and hollow duct, which allows venom from a specialized gland to pass through during the bite. This venom quickly kills the prey, allowing the wolf spider to eat in peace.

Although wolf spiders could bite a person if threatened, they prefer to run away, and their venom is not very toxic to humans. If you do get bitten, you may have some swelling and redness, but no life-threatening symptoms have been reported. Werewolves on the other hand? For these, you’re on your own!

by Larry Williams | Oct 1, 2020

Adult cicada on tree branch, Photo credit: Lyle Buss, UF Entomologist

“What is that noise,” asked the visitors to Middle Georgia when I was a teenager. They were visiting during the summer from El Paso, Texas. I asked, “What noise?” The reply, “That loud noise in the trees.” I responded, “Oh, those are cicadas.’ There are sounds that are so common that sometimes you quit hearing them.

Before the visitors left for El Paso, I made sure to show them the brown, dry shells (exoskeletons) of cicadas that are not difficult to find attached to the trunk of a Georgia pine tree during summer. Cicadas leave their nymph exoskeletons on the trunks of trees and sometimes shrubs when they shed them to become mature flying adults.

You may not have ever seen a cicada but you’ve undoubtedly heard one if you live in Florida. These insects make a loud buzzing noise during the day in the spring and summer. Male cicadas produce their distinctive calls with drum-like structures called timbals, located on the sides of their abdomens. The sound is mainly a calling song to attract females for mating.

Cicadas spend most of their life underground as nymphs (immature insects) feeding on the sap of roots, including trees, grasses as well as other woody plants. They can live 10 or more years underground as nymphs. In some parts of the United States, there will be news reports of when periodical cicadas are expected to emerge from the ground. Periodical cicada species mature into adults in the same year, usually on 13- or 17-year life cycles. Their numbers can be enormous as they emerge, gaining much local attention. However, cicada species in Florida emerge every year from late spring through fall and in much smaller numbers as compared to the periodical cicadas.

Cicada emerging from exoskeleton, Photo credit: Lyle Buss, UF Entomologist

There are at least nineteen species of cicadas in Florida, ranging from less than a ¼ inch to over 2 inches in length. Some people might be frightened by their size and sounds but thankfully cicadas don’t sting or bite. They are a food source for wildlife, including some bird species and mammals.

Very rarely, I’ll have someone ask about small twigs from trees found on the ground as a result of the female cicada’s egg-laying process. But because this is usually such a minor issue with practically no permanent damage to any tree, cicadas really aren’t considered to be a pest of any significance in Florida.

For more information on cicadas, contact the University of Florida Extension Office in your County. Or visit the following UF/IFAS web page. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/in602