by Mark Tancig | Aug 1, 2017

Florida’s panhandle has received quite a bit of rain this summer. In the last three months, depending on the location, approximately 15 to 35 inches of rain have come down, with the western panhandle on the higher end of that range. In addition to the rain, we all know how hot it has been with heat index values in the triple digits. And who can forget the humidity?! Well, these weather conditions are just the right environmental factors for many types of fungi, some harmful to landscape plants, most not.

In the classification of living things, fungi are divided into their own Kingdom, separate from plants, animals, and bacteria. They are actually more closely related to animals than plants. They play an important role on the Earth by recycling nutrients through the breakdown of dead or dying organisms. Many are consumed as food by humans, others provide medicines, such as penicillin, while some (yeasts) provide what’s needed for bread and beer. However, there are fungi that also give gardeners and homeowners headaches. Plant diseases caused by various fungi go by the names rusts, smuts, or a variety of leaf, root, and stem rots. Fungal pathogens gardeners may be experiencing during this weather include:

- Gray leaf spot – This fungus can often show up in St. Augustine grass lawns. Signs of this fungus include gray spots on the leaf (very descriptive name!). This disease can cause thin areas of lawn and slow growth of the grass.

Gray leaf spot on St. Augustine grass. Credit: Phil Harmon/UF/IFAS.

- Take-all root rot – This fungus can attack all our warm-season turfgrasses, and may start as yellow leaf blades and develop into small to large areas of thin grass or bare patches. The roots and stolons of affected grasses will be short and black.

Signs of take all root rot. Credit: UF/IFAS.

Powdery mildew – This fungus can be found on many plants, from roses to cucumbers. It looks like white powder on the leaves and can lead to plant decline.

- Armillaria root rot – This fungus can infect a variety of landscape plants, including oaks, hickories, viburnums, and azaleas. Symptoms can include yellowing of leaves and branch dieback, usually in adjacent plants. Old hardwood stumps can harbor this fungus and lead to the infection of nearby ornamentals.

Because fungi are naturally abundant in the environment, the use of fungicides can temporarily suppress, but not eliminate, most fungal diseases. Therefore, fungicides are best used during favorable conditions for the particular pathogen, as a preventative tool.

Proper management practices – mowing height, fertilization, irrigation, etc. – that reduce plant stress go a long way in preventing fungal diseases. Remember that even the use of broadleaf specific herbicides can stress a lawn and exacerbate disease problems if done incorrectly. Since rain has been abundant, irrigation schedules should be adjusted to reduce leaf and soil moisture. Minimizing injury to the leaves, stems, and roots prevents stress and potential entry points for fungi on the move.

If you think your landscape plants are suffering from a fungal disease, contact your local Extension Office and/or visit the University of Florida’s EDIS website at http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu for more information.

by Matt Lollar | Jun 29, 2017

Algal leaf spot, also known as green scurf, is commonly found on thick-leaved, evergreen trees and shrubs such as magnolias and camellias. It is in the genus Cephaleuros and happens to be one of the only plant parasitic algae found in the United States. Although commonly found on magnolias and camellias, algal leaf spot has a host range of more than 200 species including Indian hawthorn, holly, and even guava in tropical climates. Algal leaf spot thrives in hot and humid conditions, so it can be found in the Florida Panhandle nearly year round and will be very prevalent after all the rain we’ve had lately.

Symptoms

Algal leaf spot is usually found on plant leaves, but it can also affect stems, branches, and fruit. The leaf spots are generally circular in shape with wavy or feathered edges and are raised from the leaf surface. The color of the spots ranges from light green to gray to brown. In the summer, the spots will become more pronounced and reddish, spore-producing structures will develop. In severe cases, leaves will yellow and drop from the plant.

Algal leaf spot on a camellia leaf. Photo Credit: University of Florida/IFAS Extension

The algae can move to the stems and branches in more extreme cases. The algae can infect the stems and branches by entering through a small crack or crevice in the bark. The bark in that area cracks as a canker forms that eventually can girdle the branch, killing it.

Algal leaf spot on a sycamore branch. (Platanus occidentalis). Photo Credit: Florida Division of Plant Industry Archive, Bugwood.org.

Management

In most cases, algal leaf spot is only an aesthetic issue. If only a few leaves are affected, then they can just be removed by hand. \It is important that symptomatic leaves are discarded or composted offsite instead of being left in the mulched area around the trees or shrubs. If symptomatic leaves are left in the same general area then irrigation or rain water can splash the algal spores on healthy leaves and branches. Infected branches can also be removed and pruned.

Preventative measures are recommended for long-term management of algal leaf spot. Growing conditions can be improved by making sure that plants receive the recommended amount of sunlight, water, and fertilizer. Additionally, air circulation around affected plants can be increased by selectively pruning some branches and removing or thinning out nearby shrubs and trees. It is also important to avoid overhead irrigation whenever possible.

Fungicide application may be necessary in severe cases. Copper fungicides such as Southern Ag Liquid Copper Fungicide, Monterey Liqui-Cop Fungicide Concentrate, and Bonide Liquid Copper Fungicide are recommended. Copper may need to be sprayed every 2 weeks if wet conditions persist.

Algal leaf spot isn’t a major pathogen of shrubs and trees, but it can cause significant damage if left untreated. The first step to management is accurate identification of the problem. If you have any uncertainty, feel free to contact your local Extension Office and ask for the Master Gardener Help Desk or your County Horticulture Agent.

by Gary Knox | Jun 22, 2017

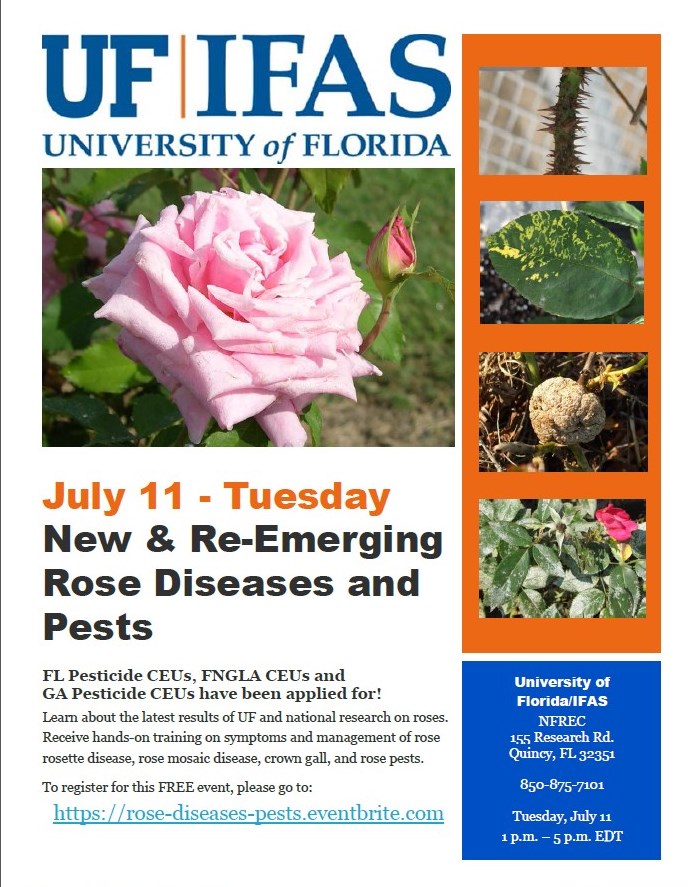

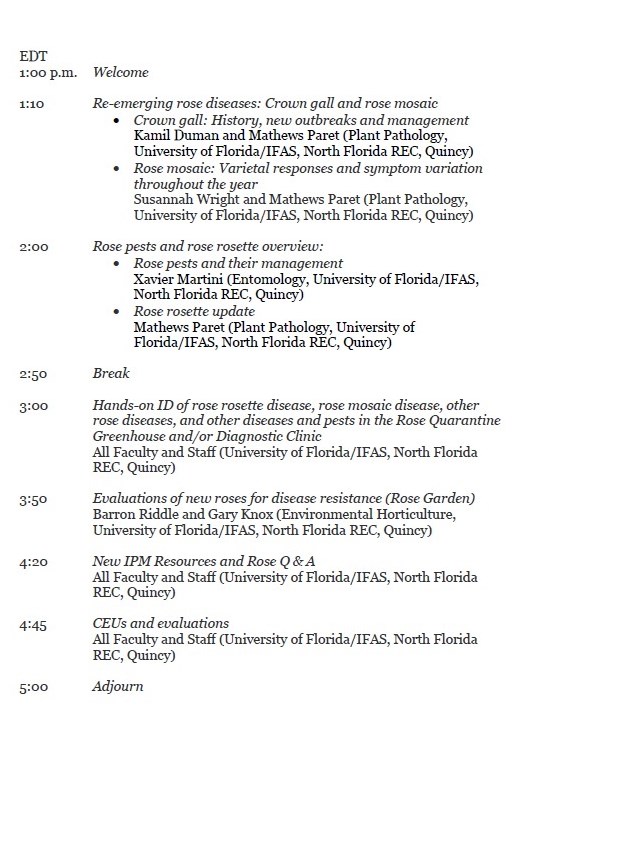

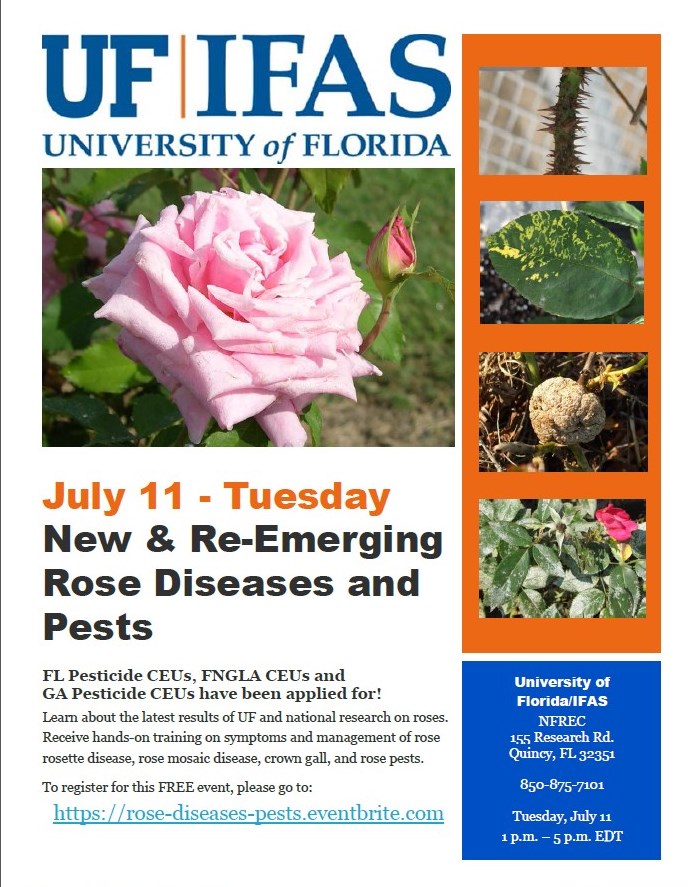

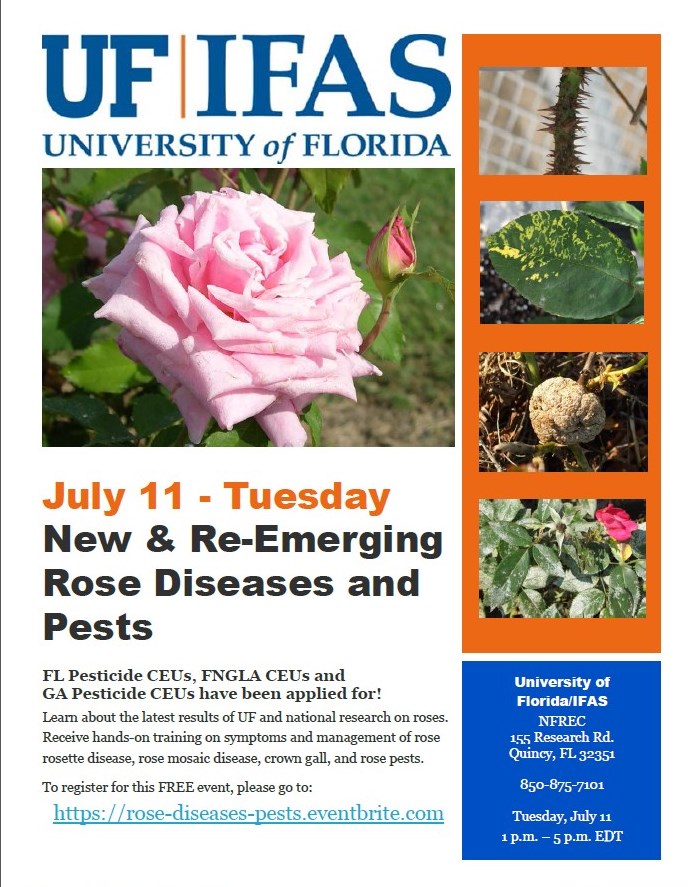

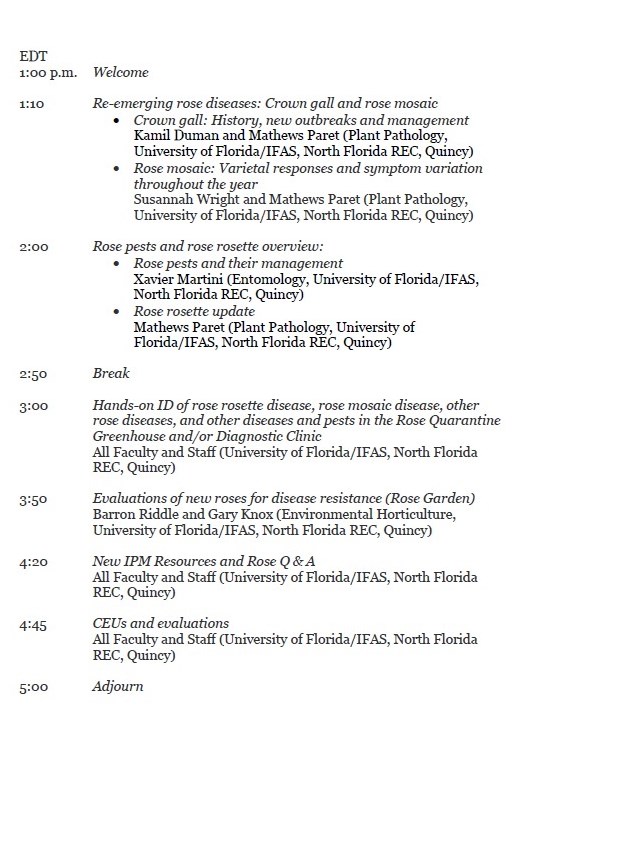

Come to this free workshop to learn about the latest results of University of Florida and national research on roses. Receive hands-on training on symptoms and management of rose rosette disease, rose mosaic disease, crown gall, and rose pests.

FL Pesticide CEUs, FNGLA CEUs and GA Pesticide CEUs have been applied for!

This program is geared for nursery and greenhouse growers, landscapers, municipal maintenance personnel, Extension personnel, Rosarians, rose enthusiasts and science teachers. Sponsored by Farm Credit of Northwest Florida and Harrell’s.

To register for this FREE event, please go to: https://rose-diseases-pests.eventbrite.com

by Carrie Stevenson | Mar 2, 2017

Small Fruit vs Normal

If we look at the big picture when it comes to invasive species, some of the smallest organisms on the planet should pop right into focus. A microscopic bacterium named Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus, the cause of Citrus Greening (HLB), has devastated the citrus industry worldwide. This tiny creature lives and multiplies within the phloem tissue of susceptible plants. From the leaves to the roots, damage is caused by an interruption in the flow of food produced through photosynthesis. Infected trees show a significant reduction in root mass even before the canopy thins dramatically. The leaves eventually exhibit a blotchy, yellow mottle that usually looks different from the more symmetrical chlorotic pattern caused by soil nutrient deficiencies.

One of the primary vectors for the spread of HLB is an insect called the Asian citrus psyllid. These insects feed by sucking juices from the plant tissues and can then transfer bacteria from one tree to another. HLB has been spread through the use of infected bud wood during grafting operations also. One of the challenges with battling this invasive bacterium is that plants don’t generally show noticeable symptoms for perhaps 3 years or even longer. As you would guess, if the psyllids are present they will be spreading the disease during this time. Strategies to combat the impacts of this industry-crippling disease have involved spraying to reduce the psyllid population, actual tree removal and replacement with healthy trees, and cooperative efforts between growers in citrus producing areas. You can imagine that if you were trying to manage this issue and your neighbor grower was not, long-term effectiveness of your efforts would be much diminished. Production costs to fight citrus greening in Florida have increased by 107% over the past 10 years and 20% of the citrus producing land in the state has been abandoned for citrus.

Classic blotchy mottle in Leaves

Many scientists and citrus lovers had hopes at one time that the Florida Panhandle would be protected by our cooler climate, but HLB has now been confirmed in more than one location in backyard trees in Franklin County. The presence of an established population of psyllids has yet to be determined, as there is a possibility infected trees were brought in.

A team of plant pathologists, entomologists, and horticulturists at the University of Florida’s centers in Quincy and Lake Alfred and extension agents in the panhandle are now considering this new finding of HLB to help devise the most effective management strategies to combat this tiny invader in North Florida. With no silver-bullet-cure in sight, cooperative efforts by those affected are the best management practice for all concerned. Vigilance is also important. If you want to learn more about HLB and other invasive species contact your local UF/IFAS Extension office.

Asymmetrical Fruit

Typical nutrient deficiencies observed in leaf, on trees with heavy fruit load. Not related to Citrus Greening (HLB)

Article by: Erik Lovestrand, UF/IFAS Franklin County Extension Director/Florida Sea Grant Agent

by Daniel J. Leonard | Jun 22, 2016

Gardeners in Northwest Florida were blessed this spring with conditions conducive to great gardening, mild weather and plenty of rain. However, with those pleasant conditions has come an unusually high occurrence of Fireblight. Cases of Fireblight have been brought into our office almost daily this spring/early summer!

Mature ‘Bradford’ Pear infected with Fireblight

Fireblight is a difficult to control, rapidly-spreading disease caused by a bacterium (Erwinia amylovora) that affects many fruit trees, especially apple and pear but is also seen on quince, crabapple, hawthorn, loquat and photinia. Fireblight is generally noticed in late winter and early spring during periods of frequent rainfall as the plant begins to bloom and leaf out. The bacterium enters the plant through the opening flowers causing them to blacken and die. The disease then makes its way down the infected stem, destroying newly developing twigs along the way. Most homeowners notice the problem at this point in the progression; the new shoots have died, turned black and hold on the plant, giving it the tell-tale “burned” look. Homeowners also generally notice sunken lesions, or cankers, that form on the infected stems.

So, with a problem as unpredictable and destructive as Fireblight, what can one do to prevent it or combat its spread? There is no one method that can prevent or cure a Fireblight infection but there are several precautions homeowners can make to mitigate its effects.

- Plant resistant species and/or resistant cultivars of susceptible species, such as pear and apple. Under conditions like we’ve had this year, no pear or apple is immune but these cultivars have some proven resistance:

- Edible Pear: ‘Keiffer’, ‘Moonglow’, ‘Orient’

- Apple: ‘Anna’, ‘Dorsett Golden’

- Ornamental Pear: ‘Bradford’, ‘Cleveland Select’

- Remove infected and dead wood when the tree is dormant. Make a clean cut at least 12” below the last sign of infected wood and dispose of it. It is always a good practice to sanitize your pruners between cuts on a diseased tree. Also, there is little evidence to suggest that pruning out diseased wood on actively growing plants has much effect on further disease spread as long as conditions are still suitable for Fireblight formation.

- If you have noticed Fireblight on your trees in the previous year, it is good practice to make a preventative spray of a copper fungicide prior to the plant breaking dormancy.

- During bloom, streptomycin may be applied every three or four days for the duration of the bloom cycle to prevent infection. Consult the label for required days between spraying and consumption.

Fireblight is bad news in a fruit orchard but homeowners can take heart in the fact that the condition is not always fatal, especially if the preventative measures outlined above (proper cultural practices, proper pesticide use, and planting of resistant cultivars) are taken!