by Evan Anderson | May 27, 2020

Two-Lined Spittlebug. Photo courtesy of Evan Anderson.

Problems with turfgrass come in all shapes and sizes. One that may affect your lawn is an insect that has two very distinct life stages. Named for the two distinct stripes on its back, the two-lined spittlebug looks like a plant or leafhopper during its adult life. When it is young, however, it is often camouflaged and not readily visible. The small green nymph hides in a mass of white froth or spittle that it secretes for protection.

The two-lined spittlebug is not a picky eater, though it cannot harm people or pets. It feeds on a variety of plants, piercing the stem or leaves with its mouthparts and sucking out the juices within. While it may not be picky, it does have favorites. Holly bushes are one food of choice for this pest and centipedegrass is another, so those growing this grass should keep an eye open. The protective spittle masses are usually close to the ground, so they may not be readily visible from above.

Centipedegrass displays feeding injury from spittlebugs in the form of purple or white striping along its leaf blades. If infestations are particularly heavy, the grass may turn yellow, then brown, and eventually curl up as the leaves die. Populations of the adults that cause most of this damage are typically largest in June, with another spike around August or September as the year’s second generation matures. Years with excess rainfall in spring and summer will see increased numbers of spittlebugs.

Spittlebug damage on Centipedegrass. Photo courtesy of Larry Williams, Okaloosa County Horticulture Agent.

If you are having a problem with these pests, make sure you are keeping your lawn as healthy as possible with good cultural practices. Proper watering, fertilization, and mowing to the appropriate height can all help to keep grass strong enough to withstand pests. Remove excess thatch, as it holds moisture and can favor the growth of spittlebugs.

Insecticides may be used to help with control as well. Options for Florida include pyrethroids such as bifenthrin, permethrin, and cyfluthrin. Products with the active ingredients imidacloprid and carbaryl are other options. Read the label of any product you choose. If you have questions or need help in identifying a pest problem in your lawn, contact your local Extension office.

by Daniel J. Leonard | May 13, 2020

It’s been a challenging spring in this guy’s garden! Despite getting the normal early start required for successful gardening in Florida, I’ve been affected by Bacterial Leaf Spot stunting my tomatoes, cutworms that reduced my watermelon plantings by half, and an eternal test of my patience in the form of a dog that seems to think my raised beds are merely a shortcut to a destination further out in the yard. My latest adversary is the most potentially destructive yet, an outbreak of Southern Armyworm (Spodoptera eridania).

Early Southern Armyworm damage on Okra seedlings. Photo courtesy of the author.

Unlike some serious garden pests that wait until the heat of summer to emerge, Southern Armyworms begin appearing in spring gardens around the end of April. Adult moths can survive mildly cold weather and venture into the Panhandle as soon as warmer spring weather arrives. Once the adult moths arrive, egg masses are then laid on the undersides of leaves and hatch in a little under a week. Once loosed upon the world, Southern Armyworm larvae (caterpillars) become indiscriminate, voracious feeders and congregate in extremely large numbers, allowing them to destroy small, developing garden vegetable plants in a manner of days. Young larvae feed on the undersides of leaves and leave little but a skeleton. As larvae grow larger, they become solitary and begin to bore into fruit. Once they’ve eaten the good stuff (leaves and fruit), large larvae turn to branches and even plant stems!

Southern Armyworm larvae feeding on Okra leaves. Photo courtesy of the author.

The good news for gardeners is that Southern Armyworm, and most other caterpillar pests, are easily controlled if outbreaks are caught early. Scouting is critical for early detection and good control. Armyworm damage generally appears from above as brownish-gray sections of affected leaves with a yellowish ring surrounding these sections, this ring indicates the current feeding zone. Affected areas will appear transparent and “lacy” due to the skeletonizing effects of larval feeding. If you see leaves that look “off” in the manner just described, check underneath for the presence of a horde of tiny greenish worms.

If found in this early stage, an application of Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt), a biological pesticide utilizing a bacterium destructive to caterpillars, is extremely effective. Bt has to be ingested by caterpillars with leaf tissue to work; thorough coverage of leaf surfaces is critical for maximum control. I generally follow up with a sequential application of Bt a day later to ensure that I achieved good coverage of the plant surfaces and, therefore, good control. Unfortunately, Bt is much less effective on older larvae. Infestations not caught early require harsher chemistries like carbamates, pyrethroids and organophosphates for adequate control.

Don’t let armyworms or other caterpillar pests destroy your garden, get out there daily and scout! You have a short window for easy caterpillar control with a harmless to people, natural product, Bt. Don’t waste it!

For more information about Southern Armyworm, other caterpillar pests, Bt, or any other horticultural topic, please consult your local UF/IFAS Extension Agent. Happy Gardening!

by Sheila Dunning | Apr 23, 2020

Members of the Phyllophaga genus are found throughout Florida and most of North America. One of them is the May/June beetle. Adults are most active during the rainy season. So in parts of the country where the wetter months are May or June, the common name of this insect makes common sense. But, when an area experiences extra rain earlier in the spring, the May/June beetle may emerge from the ground in March or April. That is what has happened in the western Panhandle this spring. May/June beetles have been leaving the soil and flying to the lights of people’s homes.

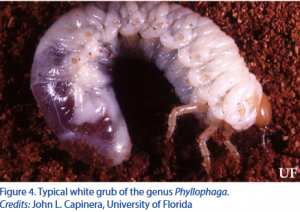

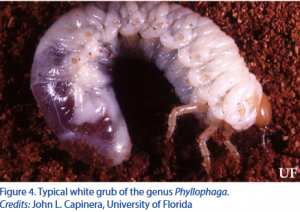

The life cycle of these beetles varies from one to four years. Eggs are laid in soil each spring by females. In 3 to 4 weeks, small grubs (larvae) hatch from eggs and develop through three stages (instars), with the first two stages lasting about 3 weeks. The larvae will move closer to the surface and back deeper in the soil as the soil temperature changes. While close to the surface, larvae feed on grass roots about one inch below the soil surface. Damaged grass turns brown and increases in size over time. Heavy infested turf feels spongy and moves when walked upon. The last larval stage remains in the soil from the fall through spring. The cool soil temperatures drive the larvae deeper in the soil where they remain relatively inactive. Typically, on the third year, white grubs pupate 3 to 6 inches deep in the soil and emerge as adults.

Larvae, called grubs, vary in length from ¾ to 1 ¾ inches depending on the stages. Grubs are white with a C-shaped body with a brown head and three pairs of legs near the head. Adults have ½ to 1 inch long, shiny bodies that are dark yellow to brownish-red in color. Adults do feed on the foliage of several species of ornamental plants, but the damage is typically only aesthetic; not causing long-term harm.

Larvae, called grubs, vary in length from ¾ to 1 ¾ inches depending on the stages. Grubs are white with a C-shaped body with a brown head and three pairs of legs near the head. Adults have ½ to 1 inch long, shiny bodies that are dark yellow to brownish-red in color. Adults do feed on the foliage of several species of ornamental plants, but the damage is typically only aesthetic; not causing long-term harm.

Monitoring of and managing emerging adults can help with deciding on the need for insecticide control for the grubs. To catch and remove adult beetles, place white buckets containing soapy water near plants that have chew marks or areas with lights at night. Leave it overnight. The beetles can easily be disposed of the next day. If there are more than 12 in the bucket be prepared to monitor the lawn for grubs. Extra rain or frequent irrigation during the adult flight time may attract more egg-laying females.

To inspect for grubs, turn over sod to a depth of at least two-inches. If there are an average of three or more per square foot, an insecticide treatment may be needed. To confirm that they are May/June beetles inspect the darkened rear of the grub. Locate the anal slit. It should be Y-shaped with two rows of parallel bristles that point toward each other. This is referred to as the raster pattern. All grub species can be identified using their unique “butt” features.

The most effective time to control this pest is summer or early fall when the larvae are small. Remove as much thatch as possible before applying an insecticide. Spot treat the off-colored area plus the surrounding 10 feet with products containing imidacloprid or halofenozide in early summer. Follow up in the fall with insecticides such as trichlorfon, bifenthrin or carbaryl if grubs persist.

by Gary Knox | Apr 23, 2020

Article by Dr. Gary Knox, Professor of Environmental Horticulture at the UF/IFAS NFREC Quincy

Introduction

Rhizomatous begonias are a large group of Begonia species, hybrids and selections characterized by large, sometimes-colorful leaves arising from thick rhizomes that grow along the soil surface. White or pink flower clusters that appear in late winter and spring are an extra bonus with these plants. Some types can be used in north Florida as herbaceous perennials that add bold leaf texture and color as well as flowers to shady gardens.

Begonia mass planting

Common rhizomatous begonias such as Begonia nelumbiifolia, ‘Erythrophylla’ (“Beefsteak”), and ‘Ricinifolia’ have long been grown outdoors in south and central Florida gardens as herbaceous perennials. North of these areas, rhizomatous begonias were considered cold sensitive and thus used strictly as pot-grown plants grown indoors or protected over winter. Nonetheless, north Florida trials testing the performance of outdoor, in-ground plantings started in Tallahassee and Gainesville as long ago as the late 1980s and early 1990s. With the proven success of some rhizomatous begonias in north Florida, interest in these plants increased rapidly in the early 2000s. Since then, savvy north Florida gardeners have been delighted by the possibility of using rhizomatous begonias as interesting herbaceous perennials for the shade garden. While temperatures below freezing can damage or kill leaves, these plants will usually produce new leaves from the rhizomes once warmer temperatures return in spring.

Plant Description Under North Florida Conditions

Leaves of rhizomatous begonias are this plant’s most distinctive feature and are why this group is so appealing to gardeners. Leaves often are large, from a few inches wide to almost 3 ft. in diameter (as reported for the cultivar ‘Freddie’ under the right conditions). Leaf shape may be rounded, star-shaped or irregularly edged, and leaf colors include burgundy, red, bronze, chartreuse, silver, and various shades of green including one so dark as to be almost black. Many types have leaves displaying patterns of one or more colors and some have silver or red markings. Undersides of leaves are often burgundy-colored, and leaf stems (petioles) also may exhibit colors other than or in addition to green. Leaves may be smooth, textured, or fuzzy-appearing due to large numbers of sometimes conspicuous hairs. Some types have leaves with an interesting three-dimensional spiral located on top of the leaf where the leaf blade attaches to the stem.

Begonia ‘Big Mac’ foliage

Rhizomatous begonia rhizomes are thickened, fleshy stems 1 to 2 in. or more in diameter that grow, branch and spread horizontally at or just below the soil surface, often in the mulch or leaf duff. Adventitious roots develop along the rhizome, and dormant buds embedded in the horizontal stem can be stimulated to grow new leaves after damage, stress or when divided. With age, as rhizomes grow outward, the oldest part of the rhizome will stop producing leaves and eventually die.

The rhizomes contain water and food reserves that allow this type of begonia to survive environmental stresses like drought as well as leaf loss or damage from cold temperatures. Shoots and roots can grow from the rhizome even if leaves and roots are killed or damaged.

Flowers occur in late winter to spring, depending on the species, cultivar and weather, and are quite showy on some selections. Flowers typically are white to various shades of pink and occur in a cluster (technically called a cyme) held above the foliage, in some cases dramatically high above the foliage. Individual flowers may range in size from 3/8-inch to over 2 inches at their widest point and a flower cluster may contain a few to over 120 individual flowers, depending on selection and growing conditions. A mature rhizomatous begonia may have an extended period of flowering, providing weeks of color. This long floral display results from large numbers of flowers developing sequentially on an individual flower cluster such that new flowers are still forming long after the first flowers have opened. Furthermore, multiple flower clusters appear over an extended time period. Flowers occasionally are pollinated and form winged seed capsules, though seed production and viability are variable. After flowering, the leaves remain a point of interest in the garden due to their size, lush appearance, interesting shapes and colorful patterns.

Cultural Requirements, Use and Maintenance

Rhizomatous begonias grow best in light shade or indirect light but can tolerate morning sun. Plants thrive in rich, organic, well-drained soil that is moist but not wet. A layer of organic mulch or leaf litter often is enough to provide basic conditions for growth in most soils if they are well-drained. Accordingly, organic mulches or leaf litter should be applied regularly around plants. Fertilizer stimulates growth but decomposing organic mulches can provide adequate nutrients, except perhaps with poor or sandy soils.

Newly planted begonias should be watered regularly. After establishment, most rhizomatous begonias benefit from regular watering but only require irrigation during periods of drought or extended dry weather.

An individual plant makes an attractive specimen plant in a container or in the garden. With time, a rhizomatous begonia can spread and, in the garden, develop into a patch. Alternatively, planting large numbers of the same rhizomatous begonia can create a very dramatic garden border, mass planting, or groundcover, especially in spring when all plants are flowering. To achieve this effect more rapidly and with smaller numbers of plants, tips of rhizomes can be pruned to stimulate rhizome branching and result in a denser plant or patch. Rhizome tip pruning should be done after plants finish flowering. Plants can be divided and moved easily since only the rhizome is needed to establish a new plant, but this should occur after flowering and early in the growing season so plants have long enough to establish before cold weather.

For aesthetic purposes, dead or damaged leaves may be removed as needed but especially after frosts and hard freezes. Similarly, leaves that overwinter often become “ratty” in appearance with time and may be removed without affecting plant growth.

Potential Problems

Rhizomatous begonias have few pests or other problems. Mealy bugs can occasionally infest plants. As with other large-leaved plants, wind or physical contact can tear and damage leaves. In north Florida, winter frosts and freezes can damage and disfigure leaves or kill leaves entirely, causing them to lose structural integrity and collapse, appearing mushy. Foliage may be protected during cold weather by frost cloth, sheets or other typical cold protection strategies, though heavy coverings could themselves damage leaves.

Rhizomes themselves usually survive cold weather because they are insulated from low temperatures by being half-buried in the ground and/or being covered by mulch. Adding mulch regularly to rhizomatous begonia plants will provide increased freeze-protection. Also, their typical planting location under tree canopies protects plants from a radiation freeze. Soil drainage is a more important factor for rhizomes since wet soil conditions could lead to rot, particularly in winter.

Common Types and their Descriptions Under North Florida Conditions

With hundreds of species and thousands of cultivars and hybrids, rhizomatous begonias can be overwhelming. Many rhizomatous begonias look alike and even experts have difficulty distinguishing species and cultivars. Many grown in north Florida have their origins in Mexico, Central and South America, though the Begonia Family is huge and species are found nearly world-wide.

Begonia heracleifolia

Technically rhizomatous begonias include Rex begonias, a group derived from Asian native, Begonia rex, and known for their especially colorful leaves. However, most Rex begonias do not grow well in Florida’s heat, high rainfall and high humidity, and so these begonias are excluded here.

Begonias listed below represent types that have proven resilient and usually cold hardy in north Florida USDA Cold Hardiness Zone 8b.

Species:

Begonia heracleifolia: The species boasts star-shaped leaves up to 6 in. across on stiff, hairy, thick leaf stems (petioles) up to 5 in. long. Each of the pointed leaf lobes is edged in dark green and has a chartreuse stripe along the central midrib, adding contrast. Spectacular sprays of pale pink flowers appear in late winter in clusters measuring 3 ½ in. by 4 ½ in. on 6-in. flower stalks (pedicels). Each cluster contains about 30 or more flowers, each about 1 in. across. As the season goes on, foliage gets showier and showier. It often dies down after winter freezes but re-emerges in late spring.

Begonia nelumbiifolia

- nelumbiifolia: This cold hardy begonia is known for its exceptionally large, water lotus-shaped leaves, creating a stunning specimen. Individual leaves can grow as large as 18 in. by 14 in. on leaf stems as long as 36 in. but 12 in. by 9 in. leaves are more typical. As temperatures warm, new developing foliage continues to get bigger, growing into very large leaves by fall. There also is a form in which the medium green leaves have red veining. White flowers are displayed above the foliage in mid to late spring in airy clusters measuring 7 ½ in. to more than 12 in. across on stems up to 48 in. tall. Clusters may contain as many as an astounding 120 flowers, each about ¾ in. across at its widest point.

2. popenoei: Huge rounded leaves with red veins and undersides make this a specimen plant which can grow to 3 ½ ft. tall and wide. Hardy with protection, it throws up tall stalks with clusters of white flowers in late winter.

Cultivars:

“Beefsteak”: This catch-all name refers to the original beefsteak begonia, ‘Erythrophylla’, as well as many derivatives that look similar. Beefsteak begonias characteristically have rounded leaves with a glossy green to bronze top surface and reddish undersides. Leaves range in size from 4 to 7 in. in diameter, and flower clusters are on stems up to 18 in. tall. ‘Erythrophylla’ was developed in 1847 and is considered a tough, vigorous plant, hence the common name, “beefsteak”. Given the long history and vigor, ‘Erythrophylla’ and derivative beefsteak begonias have long been shared as pass-along plants, world-wide as potted plants and later as an in-ground Florida garden plant. One type has ruddy, evergreen leaves and long-lasting, bold pink flower clusters. The scalloped 4-in leaves are on short 5 ½ in. reddish leaf stems but are most notable for remaining undamaged by temperatures down to the mid 20s °F, long after all other begonias’ leaves have turned to mush. Mid spring finds this plant topped by numerous clusters of dark pink flowers, with the display lasting 6 weeks or more. Individual clusters are about 8 in. by 5 in. on flower stems about 12 in. tall. Each cluster contains about 20 flowers each about ¾ in. wide at its widest point.

Begonia ‘Big Mac’ in flower

‘Big Mac’: This is a large, vigorous plant with enormous star-shaped leaves having reddish undertones and red leaf stems. The plant grows about 3 ft. tall and 2 ft. wide. Individual leaves may grow up to 18 in. wide on 16-in. leaf stems but typical leaves on younger plants are 10 in. to 12 in. wide. Individual white flowers are an amazing 2 in. wide at their widest point in clusters measuring 7 in. by 12 in. and containing about 75 flowers. Cold winters will knock it to the ground, but this begonia re-emerges again in late spring. This plant was hybridized in 1982 by Paul P. Lowe in Lake Park, Florida.

‘Joe Hayden’: This begonia features dramatic, dark, lobed leaves with burgundy undersides. Leaves are up to 8 in. long supported by leaf stems up to 9 in. long. In spring, the plant is topped by light pink flowers held high above the foliage. Each cluster measures about 5 in. by 7 in. on flower stems up to 26 in. tall. Each cluster contains more than 100 individual flowers, each about ¾ in. across at its widest point. This selection was hybridized in California in 1953 by Rudolf Ziesenhenne, but many similar selections have been made and are often confused with ‘Joe Hayden’.

Begonia ‘Joe Hayden’

Many other cultivars are common, but other cold hardy types suitable for north Florida include ‘Caribbean King’, ‘Caribbean Queen’, ‘Washington State’ and the catch-all ‘Ricinifolia’ types (with large, castor bean-shaped leaves). New breeding by scientists and enthusiasts promises to deliver many more types of rhizomatous begonias with increased foliage cold hardiness and an expanded range of foliage types and colors. A major Texas nursery introduced a series of rhizomatous begonia hybrids marketed as Crown Jewel Begonia™. The series currently features five patent-pending cultivars that are promoted as landscape plants for Zone 8. Additional breeding work is ongoing in north Florida.

Availability and Propagation

Rhizomatous begonias are available from Internet/mail order nurseries, some American Begonia Society members, other gardening groups, and plant societies. The introduction of trademarked rhizomatous begonias like Crown Jewel Begonia™ show promise for wider availability of rhizomatous begonias from nurseries.

Rhizomatous begonias are easily propagated by division, separation of rhizomes, or by rhizome pieces. When planting, place the rhizome or pieces (as small as 2 in. long) horizontally and half buried in a new in-ground location or in a container with potting soil. As with other begonia species, leaves may be used for propagation, though this method usually takes longer to achieve a size suitable for planting in the garden. Plants can be grown from seeds but production time is similarly long.

References:

American Begonia Society. (2020) https://www.begonias.org/index.htm. Accessed 15 April 2020.

Ginori, Julian, Heqiang Huo, and Caroline R. Warwick. (2020) A Beginner’s Guide to Begonias: Classification and Diversity, ENH1317. Environmental Horticulture Department, UF/IFAS Extension. January 2020. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/ep581.

Lowe, Paul. (1991) Growing Rhizomatous Begonias in the Ground in Southern Florida. Begonian 58:89. May/June 1991. https://www.begonias.org/Articles/Vol58/GrowingRhizomatousBegoniasFlorida.htm.

Schoellhorn, R. (2020) Personal communication, Alachua, FL.

Sharp, Peter G. (2011) Down to Earth – with begonias. 111 pp. http://ibegonias.filemakerstudio.com.au/PeterSharp/DownToEarthWithBegonias.pdf.

The International Database of the BEGONIACEAE. (2020) http://ibegonias.filemakerstudio.com.au/index.php?-link=Home. Accessed 16 April 2020.

UF/IFAS Gardening Solutions. (2019) Begonias. http://gardeningsolutions.ifas.ufl.edu/plants/ornamentals/begonias.html.

Watkins, Sue. (2020) Personal communication, Tallahassee, FL.

by Ray Bodrey | Apr 8, 2020

Spring has arrived and so have the insects. Caterpillars are crawling around and one possesses a unique appetite.

Neodiprion spp. is the most common defoliating insect group affecting pine trees. In all, there are 35 species that are native to the U.S. and Canada. The redheaded pine sawfly, Neodiprion lecontei, is the primary species found in the Florida Panhandle.

Adult sawflies can be as large as 1/3 of an inch in length. The female can be two-thirds larger than the male and are mostly black with a reddish-brown head, with occasional white coloration on the sides of the abdomen.

Mature larvae of the redheaded pine sawfly. Credit: Patty Dunlap, Gulf County Master Gardener.

The ovipositor, the tube-like organ used for laying eggs, is saw-like, hence the common name. During the fall, females make slits in pine needles and deposit individual eggs, up to 120 eggs at a time. The eggs are shiny, translucent and white-hued. Mature larvae (caterpillars), as seen in the accompanying photo, are yellow-green, emerge in the spring and feast on pine needles. After weeks of feeding on needles, the mature larvae drop to the ground. The cocoon, a reddish-brown, thin walled cylinder, is spun in the upper layer of the soil horizon or in the leaf litter; this is called the pupae stage. The pupae overwinter, and adults emerge from the cocoon in the spring of the following year.

Mature larvae are attracted to young, open growing pine stands. Pine is the preferred host, but cedar and fir, where native, are secondary food sources. Neodiprion lecontei is an important defoliator of commercially grown pine, as the preferred feeding conditions for sawfly larvae are enhanced in monocultures of shortleaf, loblolly, and slash pine, all of which are commonly cultivated in the southern United States. Defoliation can kill or slow the growth of pine trees as well as predispose trees to other insects or disease.

Are there control methods? Yes, biological control is a major factor, as natural enemies are numerous. Disease, viruses and predators help regulate population control. For small scale control, physically removing eggs or larvae is key. Again, most infestations occur on younger tree plantings, so they’ll be in reach. Be sure to scout young pines for signs of infestation. Horticultural soaps and oils are effective chemical controls, if needed.

For more information, contact your local county extension office.

Supporting information for this article can be found in the UF/IFAS Extension EDIS publication, “Redheaded Pine Sawfly Neodiprion lecontei” by Sara DeBerry: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/IN/IN88200.pdf

UF/IFAS Extension is an Equal Opportunity Institution.