by Rick O'Connor | Jan 20, 2022

EDRR Invasive Species

Coral Ardisia (Ardisia crenata)

photo courtesy of Les Harrison

Define Invasive Species: must have ALL of the following –

- Is non-native to the area, in our case northwest Florida

- Introduced by humans, whether intentional or accidental

- Causing either an environmental or economic problem, possibly both

Define EDRR Species: Early Detection Rapid Response. These are species that are either –

- Not currently in the area, in our case the Six Rivers CISMA, but a potential threat

- In the area but in small numbers and could be eradicated

Native Range:

Japan and northern India

Introduction:

Was introduced intentionally as an ornamental plant in the early 1900s. In 1982 it escaped cultivation and spread through wooded areas of Florida and parts of the Gulf coast.

EDDMapS currently list 2,064 records of coral ardisia. Most are in Florida but there are records in the Gulf states, Georgia, and South Carolina. Records within Florida cover the state, but has not been reported from all counties.

Within Six Rivers CISMA there are 11 records including Baldwin, Santa Rosa, Okaloosa, and Holmes Counties.

Description:

Coral ardisia grows in clumps, many times multi-stemmed in wooded areas. It has long (8”) glossy leaves that are dark green in color and has scalloped margins. The flowers are whiteish pink and droop below the leaf cover. The fruit are bright red berries that also droop from the plant and are present much of the year.

Issues and Impacts:

Like many invasive plants, coral ardisia spreads aggressively replacing native plants where they can. Though no published literature, it is believed to be toxic to livestock, pets, and humans.

It is a Category I invasive plant and a Florida Noxious Weed. It is listed as prohibited by the UF IFAS Assessment.

Management:

Step 1 is to avoid planting coral ardisia in your landscape. It is listed as a Florida noxious weed, and thus should not be sold, but transplanting is prohibited. If it can be easily removed by hand from your landscape, do so before it goes to seed. Be careful not to spread seeds.

Disking and/or burning can be effective however (a) most areas where coral ardisia grows prohibits disking and/or burning and (b) unless you removed all of the deep rhizomes it may return, so annual surveys are still needed.

Chemical treatments typically use the active ingredient triclopyr. This herbicide can be applied directly to the leaves or by applying to the bark when the plant is relatively dry. For large areas needing treatment the formulas may change. Different mixtures can be found in the references below. Annual retreatment may be required. Contact your local county extension office if you have questions.

References

Ardisia crenata. 2022. University of Florida Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. https://plants.ifas.ufl.edu/plant-directory/ardisia-crenata/.

Ardisia crenata. 2019. University of Florida IFAS Assessment of Non-Native Plants. https://assessment.ifas.ufl.edu/assessments/ardisia-crenata/.

Sellers, B.A., Enloe, S.F., Minogue, P., Walter, J. 2021. Identification and Control of Coral Ardisia (Ardisia crenata): Potentially Poisonous Plant. University of Florida IFAS Electronic Digital Information System (EDIS) publication #SS AGR-276. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/AG281.

Early Detection and Distribution Mapping System (EDDMapS)

https://www.eddmaps.org/

Six Rivers CISMA

https://www.floridainvasives.org/sixrivers/

by Rick O'Connor | Jan 13, 2022

Like many of you reading this article, I grew up here in the northern Gulf coast. I spent a lot of time at the beach and in the water enjoying this fantastic place people use to call the “miracle strip” and now call the “emerald coast”. I would spend hours swimming, fishing, crabbing, skiing (a sport that has all but disappeared around here), and just enjoying this place. With all the fishing and snorkeling we did we were familiar with many species in the area. Pinfish, flounder, mackerel, croaker to name a few. But one group of local fish I was not aware of were the killifish. I was not aware of them until I attended Dauphin Island Sea Lab to study marine biology. And then… I discovered them.

Like many who entered marine biology programs in the 1970s I was going to be an ocean going “Jacques Cousteau” studying sharks or something. But at Dauphin Island I was introduced to the amazing world of the estuary where we did a lot of work in Mobile Bay. Pulling seine nets through the numerous salt marshes over there I quickly found that one of the most abundant fish there were these fish known as killifish. They are small minnow type fish who typically run three inches or so in length. There are two who grow larger, the longnose killifish and the gulf killifish both can reach six inches and are known by local fishermen as “bull minnows”. Bull minnows are popular bait, but most fishermen do not know that the actual name of these fish are killifish. When I was in graduate school, I took a course in aquaculture, and we visited five states in five days stopping at federal, state, and private fish farms. One private farm was a “bull minnow” farm in Arkansas. This farmer was doing quite well. He had a collection of corvettes and was working on a collection of mustangs. Needless to say bull minnows are a popular bait.

But who are these abundant estuarine minnows that most are not aware of?

Well, as we said they are small. For most, their bodies are tube shaped (fusiform) and their fins are rounded, not forked. Rounded fins (truncate) are not designed for speed but for better maneuvering in and around grasses, rocks, and coral. Killifish live in the grasses of seagrass beds and shoreline marshes where these fins come in handy.

Most have an extreme tolerance for changes in salinity. The sheepshead minnow (Cyprinodon variegatus) can live in salinities as low as 0 ppt and as high as 100 ppt – mean seawater salinity is 35 ppt. Because of this high tolerance to salinity changes, many of these killifish can be found in a variety of habitats within the estuary and even in freshwater systems entering the bay. One species, the longnose killifish (Fundulus similis) seems to prefer more saline conditions. Because of this we are looking at a local project to determine which estuarine creeks this species is found. The absence of the longnose killifish could suggest freshwater discharge and, possibly, a run-off issue. But with the dramatic salinity shifts typically seen within estuaries due to tides and run-off, having a high tolerance for salinity shifts is a good adaptation to have.

According to Hoese and Moore1 there are seven species of killifish within the estuaries of the northern Gulf of Mexico.

This longnose killifish has the rounded fins of a bottom dwelling fish.

The longnose killifish (Funuduls similis) is elongated with vertical black stripes and a single dot at the base of the tail. It has an elongated snout that gives the name “longnose”. This is a very common killifish but, as mentioned above, disappears when salinities become too low. According to Hoese and Moore1 this fish is not that common along the Gulf coast of peninsula Florida. The biogeographical reason? Not sure. We know this fish does not like freshwater but the discharge in that part of the Gulf is not that different than the panhandle, in fact, it could more saline.

Saltmarsh topminnow

Photo: Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

The saltmarsh topminnow (Fundulus jenkinsi) is not as common. Its geographic range extends from Galveston Bay to the western Florida panhandle. Here in Florida, it is so rare it is a listed species. It resembles the longnose in shape and vertical stripes, which are actually rows of black dots, but the snout is short. I am not sure why this fish has not expanded its range east into the Big Bend or west towards Corpus Christi. Both of those areas seem to be higher in salinity and this may be the reason.

The gulf killifish (Fundulus grandis) is the “big boy” of the group. With a mean length of six inches this fish is often confused with “fingerling mullet” and is very popular as bait. This is the fish most often called “bull minnow”. Young will have dark stripes like the longnose but lack the “longnose” and does not have a black spot at the base of the tail. Most lose their stripes when they become older. It is found throughout the Gulf region.

The bayou killifish (Funudulus pulvereus) is another very common killifish in our area. Smaller than the gulf killifish and longnose, it can be identified by the yellowish colored anal fin. Males will have stripes while females will have spots. The coloration of these is amazing and the breeding colors of the males even more so. Hoese and Moore1 report this fish only from southern Texas to Alabama, but we have often found them here in Pensacola. I am not sure how far east they exist, but there must be some barrier in Florida waters to impede their dispersal there.

Sheepshead Minnow

Photo: University of Florida

The sheepshead minnow (Cyprinodon variegatus) is the champion of salinity tolerance. They are found in many estuarine habitats and even some extreme ones where no other fish are found. Hoese and Moore1 report that it has the highest tolerance of any fish in the world. There are records of this fish living in waters over 100 ppt (note: the average salinity for the ocean is 35 ppt). As you might expect, it has the largest range as well. This fish had been reported from Maine, down the entire east coast, the Gulf of Mexico, and as far south as Venezuela. It is not as elongated as most killifish, having a more short and stout appearance. They have dark vertical bars on their bodies and the males produce a beautiful iridescent blue color on their backs during breeding.

Diamond Killifish

Photo: University of Florida

The diamond killifish (Adinia xenica) is one that I have not collected very often. It resembles the sheepshead minnow is shape and color but has a more pointed snout and the teeth are compressed instead of conical, as they are in the sheepshead minnow. This fish is restricted to the western Gulf of Mexico but is found here in the Florida panhandle. It usually is in a group with other killifish, so, you would have to look hard in your sample to see if you have it.

Rainwater Killifish

Photo: Florida Museum of Natural History

Finally, there is the rainwater killifish (Lucania parva). This is a more elongated form with no markings on the body at all. At first glance, after seeing other types of killifish, it would not appear to be a killifish at all. It is one of the smaller killifish (2 inches) and is often found in freshwater creeks feeding into the bays. The males will have a reddish-orange anal fin during breeding season. It does have a large range extending from New England to Mexico.

These are truly amazing fish. They are extremely abundant and hardy. For those prone to use small nets collecting fish along the shorelines, grassbeds, and salt marshes, they will find this group very common, and most do well in aquariums.

Reference

1 Hoese, H.D., Moore, R.H. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M Press, College Station TX. Pp. 327.

by Rick O'Connor | Jan 13, 2022

Six Rivers “Dirty Dozen” Invasive Species

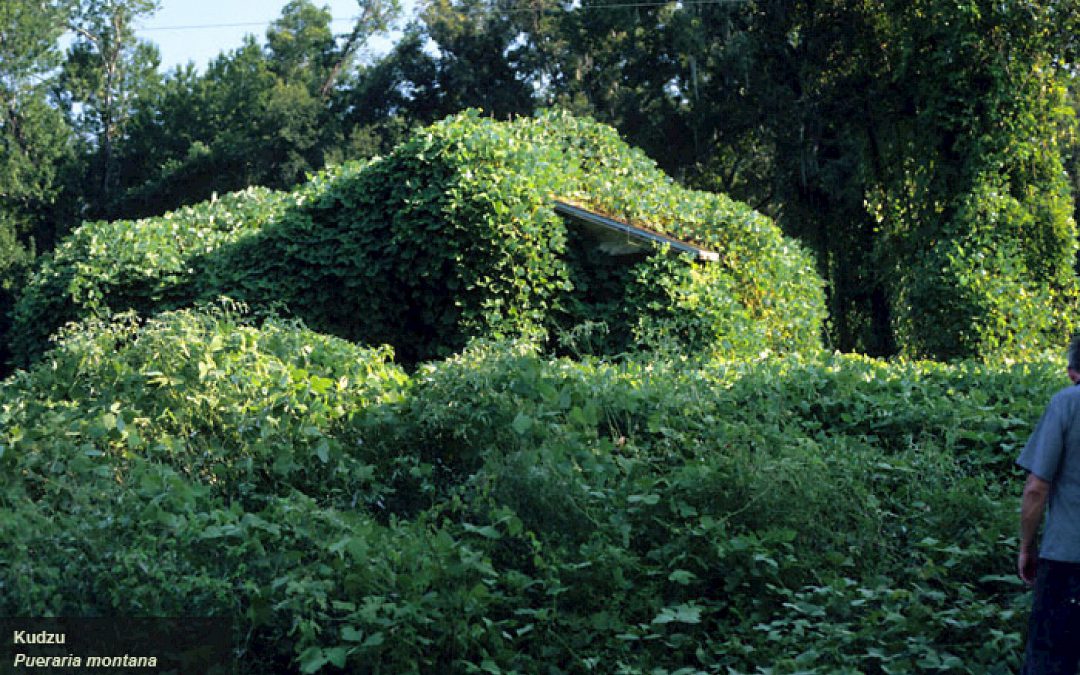

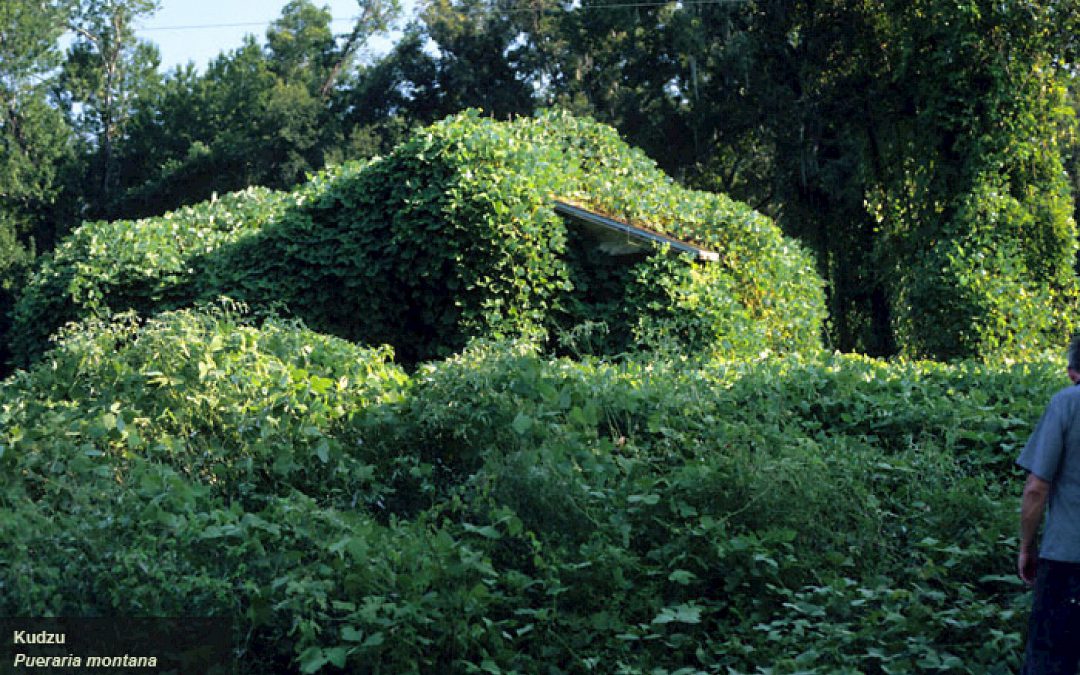

Kudzu (Pueraria montana)

Kudzu is an aggressive growing vine found throughout the southeast.

Photo: UF IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants.

Define Invasive Species: must have all of the following –

- Is non-native to the area, in our case northwest Florida

- Introduced by humans, whether intentional or accidental

- Causing either an environmental or economic problem, possibly both

Define “Dirty Dozen” Species:

These are species that are well established within the CISMA and are considered, by members of the CISMA, to be one of the top 12 worst problems in our area.

Native Range:

Eastern Asia.

Introduction:

Kudzu was first brought to the U.S. for the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition in 1876. Seven years later it was presented at the New Orleans Exhibition. Seed was sold to grow ornamental vines to shade porches and was also tried as livestock feed. It now covers about 2 million acres of forest land in the southern U.S.

EDDMapS currently list 11,288 records of the plant in the U.S. As with many “dirty dozen” species, this is certainly under reported. Most are in the southeastern U.S. but there are records in Kansas, Illinois, and Oregon. It has been reported throughout the state of Florida including the Florida panhandle, and all of the Six Rivers CISMA.

Description:

This is a semi-woody vine that can grow up to 100 feet. Most who have seen it, recognize it immediately. The leaves are large (4”) and alternate on the vine forming three leaflets at each node. The leaves are lobed with hairy margins. The vines can reach 4” in diameter and one stump found in Georgia was 12” in diameter. The flowers are purple in color, hang in clusters, and appear in late summer.

Issues and Impacts:

It grows almost anywhere and over almost anything. Entire buildings have been completely covered by this plant and it has also been known to grow over and uproot trees. Any vegetation it covers will soon die due to a lack of sunlight and it is also known to harbor insects and disease for native legumes, many of which are important agricultural crops, such as soybeans. It is listed as a state noxious weed.

Management:

This is a tough plant to control. It has been reported to grow as much as a foot a day. The root and rhizomes system are extensive and reach depths of 10 feet. There are also tubers that store excess carbohydrates that help with surviving drought, freezing, and even fires.

Herbicides are effective on small patches, though repeated applications may be needed. They can be used on large areas of infestation but will certainly take repeated applications over years and can be very expensive. Many will include burning, disking, or mowing before chemical applications to weaken the root system. Chemicals that have had some success include glyphosate, chlopyraild, metsulfuron, and aminopyralid.

Many have had success using livestock grazing, such as goats or cattle. Research has shown that close grazing, where 80% of more of the plant is removed, can completely eradicate it over a couple of years. One source recommends eight goats / acre for best results. Others have had some success by cutting the plant back (like grazing) during the hottest times of the year.

No biological controls have been approved yet, but research continues.

In Asia the plant is used in a variety of ways including food, fiber, and medicine. These could be options for management as well.

For more information on this Dirty Dozen species, contact your local extension office.

References

University of Florida IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Kudzu (Pueraria montana). https://plants.ifas.ufl.edu/plant-directory/pueraria-montana/.

Frank, M.S. 2021. Five Facts: Kudzu in Florida. Florida Museum of Natural History. https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/science/five-facts-kudzu-in-florida/.

Early Detection and Distribution Mapping System (EDDMapS)

https://www.eddmaps.org/

Six Rivers CISMA

https://www.floridainvasives.org/sixrivers/

by Rick O'Connor | Jan 6, 2022

During 2022 I plan to make weekly hikes on Pensacola Beach to see what sort of wildlife, or other natural phenomena, I encounter each month. For the first January trip I did a short hike at Ft. Pickens on the west end of Santa Rosa Island.

Ft. Pickens is more wooded than much of the island and provides both maritime forest and beach habitats for a variety of wildlife. On my first trip – Jan 6 – the temperature was 62°F and overcast. It actually rained some during the hike. As I approached the fort area, I saw a bald eagle sitting on a sand dune.

A bald eagle sitting on a dune near Pensacola Beach.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Everyone gets excited about seeing a bald eagle. Its like dolphins, no matter how many times you see them, it is still cool, and you alert everyone they are there. The difference with bald eagles is that they were not always here. Growing up in Pensacola I rarely saw one. I worked for a period of time on what were called “the ponds” on the property of Air Products in Pace, Florida. The ponds were a water treatment system to help improve water quality coming from the plant being discharged into Escambia Bay. It was a wildlife sanctuary and there was plenty of wildlife there. Cottonmouths, deer, turtles, raccoons, and alligators were all common. One of the largest eastern diamondback rattlesnakes I have ever seen was found there. And, during the winter months, we would occasionally get a bald eagle. It was rare and very exciting.

A field guide of Birds of the Eastern United States published by Roger Tory Peterson in 1980 indicates that their winter breeding range includes much of Florida. A document published by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife suggest they begin building nests in our area in September, lay eggs by October, and hatching occurs in November. Between November and March, the parents take care of them until the fledge and head out on their own. The reason we have not seen more in our younger years was their population was down. The decline of the national bird was due to a variety of reasons, but the DDT story played a role.

Today their numbers have rebounded and encounters with them in our area have increased. Their nest can be quite large and are usually close to a water source. These birds are known as predators but actually spend a lot of time feeding on carrion and robbing other birds of their food source. Competition between the osprey, another recovering species, and bald eagles are quite famous. And, like I said, you never get tired of seeing them. This time of year, you can spot them in several locations around the beach areas.

Other creatures found on this January hike at Ft. Pickens included:

Great blue herons use tall pines for nesting during winter.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Mockingbirds are quite common in the winter. This one was feeding on the red berries of a yaupon holly.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

This green blob is actually a sea slug known as a sea hare. It was returned to the water.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

This structure is often found on panhandle beaches. It is the egg case of the snail known as the moon snail. Also called the “shark’s eye” or “cat’s eye”.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Unfortunately dead seabirds on the beach are not uncommon. This one is a pelican.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

I encourage to take some time this winter and go for a hike and see what you can discover.

by Rick O'Connor | Jan 6, 2022

Over the years I have received many calls from beach residents with concerns about coyotes. Encounters with this animal can be unnerving for many and the most common time of year for them is winter.

Coyote seen on Pensacola Beach.

Photo: Kristen Marks

A friend of mine who lives in the central part of Escambia County, told me he had seen several coyotes over Christmas break and several more along I-10 while driving back and forth from Mobile Alabama. Winter is breeding time for these animals. Early in the breeding season males are on the move seeking mates. Their searching may lead them to move at all times of the day and not just the dawn/dusk and evening times they typically do. Hence, more encounters.

Once pregnant, the females will find a den to give birth and care for the young. Dens are usually burrow areas, under logs, or within thick vegetation, but sometimes they have been found under decks or other debris in the yard. Gestation is about two months, and a litter is typically about six pups. Once born, the female will need to feed her young and will seek food from a lot of places and during all parts of the day. Hence, more encounters.

Coyotes are omnivores and have a wide diet. During the cold months their natural prey would be rodents and birds, but garbage and left out pet food are much easier to grab than birds and mammals, has a stronger smell, and higher caloric intake. It is more desired. Encounters with pet food can led to encounter with pets, and this could end bad for the pet. It is recommended that during these colder months you feed your pets, and store their food, indoors. Keeping your small pets indoors at night is recommended as well. Close and secure your garbage as best you can. Coyotes are pretty intelligent and will make an attempt to access this garbage if given the opportunity. Note that intentionally feeding a coyote is illegal. They have a natural fear of humans and if they are being fed, they will lose this fear which could lead to negative encounters with the animal.

A coyote is seen racing down Via DeLuna Blvd on Pensacola Beach

Photo: Shelley Johnson

Some may be concerned about the “pack behavior” of coyotes. Most are solitary but small packs of about six animals are known to move about the landscape usually calling to each other near dawn and dusk with their iconic howls and yips. The typical range for a group of six is about 10 square miles, which would lead to the argument that there are not many resident coyotes on Pensacola Beach or Perdido Key, but we know they are there. Some coyotes have been seen crossing the Bob Sikes Bridge between Pensacola Beach and Gulf Breeze near dawn, suggesting coyotes residing in Gulf Breeze may be using resources on Pensacola Beach.

If an encounter does happen, you should hold your ground. Coyotes do have a natural fear of humans and will typically flee. I recently encountered three animals napping near a large fallen tree while hiking in Colorado. I was not 100% sure what they were when I first saw what appeared to be ears sticking above the tree. Then a head popped up to look at me. I slowly approached, not recommended, and the coyotes immediately got up and ran. This is what you would expect them to do. Coyotes standing their ground and not leaving could suggest and animal who has found a reliable food source and may be willing to defend it. Contact the authorities if you believe this is the case.

A coyote moving on Pensacola Beach near dawn.

Photo provided by Shelley Johnson.

We do not know how many coyotes live in Escambia and Santa Rosa Counties, but it is fair to say they are common. Encounters are rare and the animal has learned to live near us without provoking problems. All the same, being aware of pets, pet food, and garbage this time of year is a good practice.