by Ray Bodrey | May 21, 2017

Hurricane season begins this year on June 1st and ends November 30th. As Floridians, we face the possibility of hurricanes each year. This simply goes with the territory. During these months, it’s important to plan for the threat of a hurricane, and at the same time hope, it never happens.

First and foremost, you may be asked to leave your home in emergency conditions. Emergency management officials would not ask you to do so without a valid reason. Please do not second guess this request. Leave your home immediately. Requests of this magnitude will normally come through radio broadcasts and area TV stations.

Figure 1. UF/IFAS Disaster Handbook.

Credit. UF/IFAS Communications.

The most important thing to keep in mind is to have your own, up to date plan for a possible evacuation. The University of Florida has developed, “The Disaster Handbook” to help citizens plan for safety. The handbook includes a chapter dedicated to hurricane planning. The chapter can be downloaded in pdf at http://disaster.ifas.ufl.edu/chap7fr.htm.

Utilizing the 15 principles below will assist you in your evacuation planning efforts:

- Know the route & directions: keep a paper state map in your vehicle. Be prepared to use the routes designated by the emergency management officials.

- Local authorities will guide the public: Stay in communication with local your local emergency management officials. By following their instructions, you are far safer.

- Keep a full gas tank in your vehicle: During a hurricane threat, gas can become sparse. Be sure you fill your tank in advance of the storm.

- One vehicle per household: If evacuation is necessary, take one vehicle. Families that carpool will reduce congestion on evacuation routes.

- Powerlines: Do not go near powerlines, especially if broken or down.

- Clothing: Wear clothing that protects as much area as possible, but suitable for walking in the elements.

- Disaster Kit: Create a kit complete with a battery powered NOAA weather radio, extra batteries, food, water, clothing and first aid kit. The kit should have enough supplies for at least three days.

- Phone: Bring your cell phone & charger.

- Prepare your home before leaving: Lock all windows & doors. Turn off water. You may want to turn off your electricity. If you have a home freezer, you may wish not too. Leave your natural gas on, unless instructed to turn it off. You may need gas for heating or cooking and only a professional can turn it on once it has been turned off.

- Family Communications: Contact family and friends before leaving town, if possible. Have an out of town contact as well, to check in with regarding the storm and safety options.

- Emergency shelters: Know where the emergency shelters are located in your vicinity.

- Shelter in place: This measure is in place for the event that emergency management officials request that you remain in your home or office. Close and lock all window and exterior doors. Turn off all fans and the HVAC system. Close the fireplace damper. Open your disaster kit and make sure the NOAA weather radio is on. Go to an interior room without windows that is ground level. Keep listening to your radio or TV for updates.

- Predetermined meeting place: Have a spot designated for a family meeting before the imminent evacuation. This will help minimize anxiety and confusion and will save time.

- Children at school: Have a plan for picking up children from school and how they will be taken care of and by whom.

- Animals and pets: Have a plan for caring for animals and shelter options in the event of an evacuation. For livestock, contact your local county extension office.

Following these steps will help you stay safe and give you a piece of mind, during hurricane season. Contact your local county extension office for more information.

Supporting information for this article can be found in the UF/IFAS EDIS publication, “Hurricane Preparation: Evacuating Your Home”, by Elizabeth Bolton & Muthusami Kumaran: http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/FY/FY74700.pdf

UF/IFAS Extension is An Equal Opportunity Institution.

by Rick O'Connor | Feb 18, 2017

It was February 13, 2017 and the temperature was 74°F… 74! It has been one strange winter. The azaleas in my yard have already bloomed, friends of mine have seen butterflies already forming chrysalis, and I have already had to deal with mosquitos; all of this in February. But, even as we talk about how warm this winter has been in the panhandle, they are having record snowfall in the Midwest and Northeast. It has been a strange winter.

Azaleas typically bloom near Easter. These bloomed in mid-February in 2017.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

It is easy to change this discussion to climate change, but we have had weird winters before. There was the winter when George Washington crossed the Delaware, apparently colder than normal for that part of the country that year. I remember as a kid having to wear a heavy coat to school in the winter and frost was on the ground most mornings – I grew up in the panhandle by the way.

In the book Sea Level Rise in Florida; Science, Impacts, and Options, Dr. Albert Hine (University of South Florida) explains why these periodic cold and warm years occur. Our orbit around the sun is not a perfect circle; the elliptical path can adjust our distance and change the amount of solar radiation we receive from Mother Sun. Then there is the wobble effect. The rotation of the Earth on its axis is similar to a spinning top, and the wobble can alter the amount of solar radiation we receive. These orbits and rotations explain the ice age and warm periods have experienced, and Dr. HIne provides geologic evidence that supports these climate change periods. The weird thing is, based on our current orbit/rotation pattern we should be in a cooling period and heading towards an ice age. But we are not, actually the last three years have been the warmest on record. So, if the stars say we should be heading towards a cooling period, and it is warming, the question begs – why?

Well, Dr. Hine suggest that it must be our activities. Man has made so many changes that have affected our planet in so many ways that some are saying we are in a period of the Earth’s history they are calling “Anthropocene”. It is hard to argue with it. Look out your window next time you are flying and see how we have changed the landscape. You cannot see these changes as you fly over the ocean, but the changes are there. Warm surface water usually overrides cooler waters at depth. The circulation of warm and cold water due to differences in density cause the currents, which cause the wind patterns, which effects our climate. The ocean is a great absorber of heat, and it is doing just that – absorbing heat, which is now reaching deeper depths. This will certainly effect the currents and the climate. Most will point at the use of fossil fuels as the change that has had the biggest impact on all of this.

So, if this is the case, what do we do about it?

Well there are models predicting what the future climate and sea levels might be, based on potential use of resources. There is nothing, at the moment, that suggest we are going to do anything different in how we use these resources so we can expect these climate changes to continue. Will 2017 follow the current trend and become the warmest year on record yet? Will flowering plants alter their cycles based on temperatures? Are rainfall patterns going to change? Will tropical species, including invasive ones, be able to colonize north Florida? I am not sure, but I think we should consider these possibilities as we plan for our future use of the landscape. Until then, we should enjoy the nice February we are having, and hope July and August are not too bad. We will see what next year brings.

If you are interested in reading more about the science of Florida’s climate, I recommend reading

Seal Level Rise in Florida; Science, Impacts, and Options. Hines, Chambers, Clayton, Hafen, and Mitchum. 2016. University Press of Florida. ISBN 9780813062891.

by Will Sheftall | Oct 22, 2016

What do the Ochlockonee and Aucilla rivers have in common? Not much, it would seem, beyond the fact that both have headwaters in Georgia and flow through Florida to the Gulf of Mexico. These two rivers do share the distinction of being unusual, although they’re unusual in very different ways.

The Ochlockonee runs yellow-brown between Leon and Gadsden counties.

Photo: Rosalyn Kilcollins

The Aucilla is a blackwater stream that goes underground and rises again before reaching the Gulf – a disappearing act that has fascinated early settlers, paddlers and naturalists alike. The Aucilla drains a smaller watershed, has lower flows, and features stream channel sediments that are predominantly sands and decaying organic material – the sediment signature of coastal plain streams with water stained dark brown, the color of tea.

In fact, blackwater rivers like the Aucilla get their color by steeping fallen and decaying tree leaves and twigs in slow-moving water, just as we steep shredded tea leaves or ground up coffee beans to dissolve their tannic acids into beverages. Blackwater steeping occurs in swamp forests up river tributaries, and in oxbow sloughs and other quiescent side channels of the downstream reaches. These form as a river “in flood” meanders and changes course within its floodplain.

The Ochlockonee is unusual among rivers originating in the Coastal Plain: in its upper reaches it has alluvial characteristics common to streams flowing from the Piedmont. The Ochlockonee drains soils rich in silt and clay that give it a yellowish brown color when those extremely fine sediments are suspended in the water. Land use activities such as paving roads and tilling farm fields elevate the fine sediment load when it rains by setting up larger volumes of fast-moving runoff. Higher rain runoff volume and velocity conspire to erode bare fields, construction sites and river banks, accentuating this river’s color.

But in spite of these differences, the Aucilla and Ochlockonee were once branches of the same river drainage system – the Paleo-Ochlockonee River. How could that possibly be? Well, sea level rise has drowned the lower reaches of this once mightier river, leaving its upper branches to empty into the Gulf separately, as smaller streams.

Sea level along Florida’s Big Bend coastline has been rising since the end of Earth’s last Ice Age – roughly 18,000 years ago. Our shallow, gently sloping underwater continental shelf was exposed during that last period of glaciation. As higher temperatures began melting ice sheets, not only did sea level rise, but more water evaporated and fell as rain. Southeastern rivers began carrying greater volumes of water.

Before annual rainfall reached today’s level during this prehistoric period of climate change, it is likely that the Aucilla from headwaters to Gulf was even more discontinuous than it is today. A current hypothesis is that the Aucilla was more like a string of sinkholes than a river, resembling its lower reaches today in a section known as the “Aucilla Sinks.”

The Aucilla is a tannic river. Thus not as yellow-brown but rather more “blackwater”.

Photo: Jed Dillard

But the nature of the Paleo-Aucilla is just one part of this intriguing story. Using sophisticated technology, scientists have discovered clues about the ancient route of the entire Paleo-Ochlockonee as it meandered across that more expansive, exposed Continental shelf to the Gulf.

In their 2008 publication Aucilla River, Tall Timbers Research Station & Land Conservancy reports that, “Ten thousand years ago, the Florida coastline was located 90 miles away from its present position. Scientists have discovered a buried river drainage system indicating that approximately 15 to 20 miles offshore from today’s coast — and now underwater — the Aucilla River combined with the Ochlockonee, St. Marks, Pinhook, and Econfina rivers to create what archeologists call the Paleo-Ochlockonee, which flowed another 70 miles before reaching the Gulf.”

“Well, I’ll be!” you say, “That’s all pretty cool to think about.” That was my reaction, too, until I remembered that this process of sea level rise continues still, albeit at an accelerating rate thanks to global warming. Which means our rivers that join forces today before emptying into the Gulf will one day be separated. Sea level rise eventually will dismember the Wakulla from the St. Marks, and the Sopchoppy from the Ochlockonee – but thankfully not in our lifetime.

True, that’s happened before, but long before humans were on the scene. Today and for many tomorrows to come, I am grateful that we and our children and grandchildren have a wonderful watery world patiently awaiting our exploration, not far beyond the urban bustle of Tallahassee.

We’re far removed in time from the first humans beckoned by these rivers. A pause in the rate of sea level rise 7,000 years ago enabled development of coastal marsh ecosystems and more successful human habitation – supported in part by the bounty of fish and shellfish that depend on salt marshes. Farther upstream and still inland today, the sinks and lower reaches of the Aucilla hold archaeological sites about twice that old, that are integral to our evolving understanding of very early prehistoric human habitation on the Gulf Coastal Plain.

If you’re intrigued by the myriad of fascinating rivers and wetlands of the Big Bend region – this globally significant biodiversity hotspot we live in, and want to experience some of them first-hand, you’re in luck. Several Panhandle counties offer Florida Master Naturalist courses on Freshwater Systems (and also courses on Upland Habitats and Coastal Systems). You can check the current course offerings at: http://conference.ifas.ufl.edu/fmnp/

You can also explore on your own. There are many public lands in our region (and across the Panhandle) that provide good access.

Go see the Aucilla’s remaining string of sinks by hiking a short segment of the Florida Trail through the Aucilla Wildlife Management Area in Taylor County. And the Ochlockonee’s floodplain of sloughs and swamps, bluffs and terraces by taking trails that follow old two-track roads “down to the river” through the Lake Talquin State Forest in Leon County.

Get some maps of your public lands, get some tips on trails, get outside, and go exploring!

by Will Sheftall | Jul 22, 2016

Birds, migration, and climate change. Mix them all together and intuitively, we can imagine an ecological train wreck in the making. Many migratory bird species have seen their numbers plummet over the past half-century – due not to climate change, but to habitat loss in the places they frequent as part of their jet-setting life history.

Migrating songbirds forage for insects in coastal scrub-shrub habitat. Photo credit: Erik Lovestrand, UF IFAS Extension

Now come climate simulation models forecasting more change to come. It will impact the strands of places migrants use as critical habitat. Critical because severe alteration of even one place in a strand can doom a migratory species to failure at completing its life cycle. So what aspect of climate change is now threatening these places, on top of habitat alteration by humans?

It’s the change in weather patterns and sea level that we’re already beginning to see, as the impacts of global warming on Earth’s ocean-atmosphere linkage shift our planetary climate system into higher gear.

For migratory birds, the journey itself is the most perilous link in the life history chain. A migratory songbird is up to 15 times more likely to die in migration than on its wintering or breeding grounds. Headwinds and storms can deplete its energy reserves. Stopover sites for resting and feeding are critical. And here’s where the Big Bend region of Florida figures prominently in the life history of many migratory birds.

According to a study published in March of this year (Lester et al., 2016), field research on St. George Island documented 57 transient species foraging there as they were migrating through in the spring. That number compares favorably with the number of species known to use similar habitat at stopover sites in Mississippi (East Ship Island, Horn Island) as well as other central and western Gulf Coast sites in Alabama, Louisiana, and Texas.

We now can point to published empirical evidence that the eastern Gulf Coast migratory route is used by as many species as other Gulf routes to our west. This confirmation makes conservation of our Big Bend stopover habitat all the more relevant.

The authors of the study observed 711 birds using high-canopy forest and scrub/shrub habitat on St. George Island. Birds were seeking energy replenishment from protein-rich insects, which were reported to be more abundant in those habitats than on primary dunes, or in freshwater marshes and meadows.

So now we know that specific places on our barrier islands that still harbor forests and scrub/shrub habitat are crucial. On privately-owned island property, prime foraging habitat may have been reduced to low-elevation mixed forest that is often too low and wet to be turned into dense clusters of beach houses.

Coastal slash pine forest is vulnerable to sea level rise. Photo credit: Erik Lovestrand, UF IFAS Extension

Think tall slash pines and mid-story oaks slightly ‘upslope’ of marsh and transitional meadow, but ‘downslope’ of the dune scrub that is often cleared for development.

“OK, I get it,” you say. “It’s as if restaurant seating has been reduced and the kitchen staff laid off. Somebody’s not going to get served.” Destruction of forested habitat on our Gulf Coast islands has significantly reduced the amount of critical stopover habitat for birds weary from flying up to 620 miles across the Gulf of Mexico since their last bite to eat.

But why the concern with climate change on top of this familiar story of coastal habitat lost to development? After all, we have conservation lands with natural habitat on St. Vincent, Little St. George, the east end of St. George, and parts of Dog Island and Alligator Point. Shouldn’t these islands be able to withstand the impacts of stronger and/or more frequent coastal storms, and higher seas – and their forested habitat still serve the stopover needs of migratory birds?

Let’s revisit the “low and wet” part of the equation. Coastal forested habitat that’s low and wet – either protected by conservation or too wet to be developed – is in the bull’s eye of sea level rise (SLR), and sooner rather than later.

Using what Lester et al. chose as a reasonably probable scenario within the range of SLR projections for this century – 32 inches, these low-elevation forests and associated freshwater marshes would shrink in extent by 45% before 2100. It could be less; it could be more. Conditions projected for a future date are usually expressed as probable ranges. Experience has proven them too conservative in some cases.

The year 2100 seems far away…but that’s when our kids or grandkids can hope to be enjoying retirement at the beach house we left them. Hmm.

Scientists CAN project with certainty that by the time SLR reaches two meters (six and a half feet) – in whatever future year that occurs, 98% of “low and wet” forested habitat will have transitioned to marsh, and then eroded to tidal flat.

But before we spool out the coming years to a future reality of SLR that has radically changed the coastline we knew, let’s consider where the crucial forested habitat might remain on the barrier islands of the next generation’s retirement years:

It could remain in the higher-elevation yard of your beach house, perhaps, if you saved what remnant of native habitat you could when building it. Or if you landscaped with native trees and shrubs, to restore a patch of natural habitat in your beach house yard.

Migratory songbird stopover habitat saved during beach house construction. Photo credit: Erik Lovestrand, UF IFAS Extension

We’ve all thought that doing these things must be important, but only now is it becoming clear just how important. Who would have thought, “My beach house yard: the island’s last foraging refuge for migratory songbirds!” even in our most apocalyptic imagination?

But what about coastal mainland habitat?

The authors of the March 2016 St. George Island study conclude that, “…adjacent inland forested habitats must be protected from development to increase the probability that forested stopover habitat will be available for migrants despite SLR.” Jim Cox with Tall Timbers Research Station says that, “birds stop at the first point of land they find under unfavorable weather conditions, but also continue to migrate inland when conditions are favorable.”

Migratory birds are fortunate that the St. Marks Refuge protects inland forested habitat just beyond coastal marshland. A longer flight will take them to the leading edge of salty tidal reach. There the beautifully sinuous forest edge lies up against the marsh. This edge – this trailing edge of inland forest – will succumb to tomorrow’s rising seas, however.

Sea level rise will convert coastal slash pine forest to salt marsh. Photo credit: Erik Lovestrand, UF IFAS Extension

As the salt boundary moves relentlessly inland, it will run through the Refuge’s coastal buffer of public lands, and eventually knock on the surveyor’s boundary with private lands. All the while adding flight miles to the migration journey.

In today’s climate, migrants exhausted from bucking adverse weather conditions over the Gulf may not have enough energy to fly farther inland in search of forested foraging habitat. Will tomorrow’s climate make adverse Gulf weather more prevalent, and migration more arduous?

Spring migration weather over the Gulf can be expected to change as ocean waters warm and more water vapor is held in a warmer atmosphere. But HOW it will change is difficult to model. Any specific, predictable change to the variability of weather patterns during spring migration is therefore much less certain than SLR.

What will await exhausted and hungry migrants in future decades? Our community decisions about land use should consider this question. Likewise, our personal decisions about private land management – including beach house landscaping. And it’s not too early to begin.

Erik Lovestrand, Sea Grant Agent and County Extension Director in Franklin County, co-authored this article.

by Rick O'Connor | Jan 19, 2016

In our last article about the red tides we discussed how the strange weather of 2015 caused some changes in the natural world around Pensacola Beach – mainly, it got warmer. Though climate change is happening, and we just had a major summit on the topic in Paris, the warming of 2015 was most directly impacted by one of the strongest El Niño’s on record.

What is an El Niño?

It is a term most of us have heard and know it has something to do with the climate – that it is associated with warming – but little else about it. It is a climatic phenomena that has been occurring for centuries. It was first reported by Peruvian fishermen around Christmas time – hence the name El Niño (“the child”).

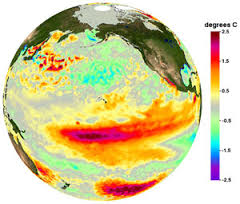

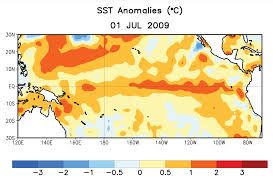

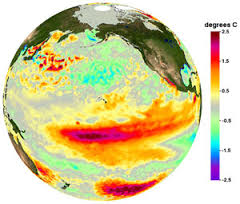

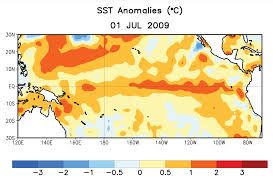

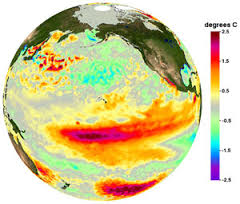

The red indicates warm water temperatures. Notice the warm temps in the eastern Pacific – not normal.

Graphic: NOAA

The ocean currents off the coast of Peru, and California, are quite cold – in the 55 F range. These cold currents move from the poles towards the equator along the coast. These cold currents keep the precipitation low and the air dry – “it never rains in Southern California”. Mountains and deserts are associated with these regions as well. The cool air at the top of the mountains flows down and across the landscape towards the ocean – causing the surface waters along shore to move offshore – thus creating a current from the ocean floor to rise to the surface called an upwelling. These upwellings bring with them an abundance of nutrients and, mixed with the high oxygen content of the colder water, provide a soup for plankton growth which is food for an abundance of fish – these are some of the richest fishing grounds in the world.

Every so many years the fishermen noticed the fish would disappear. It usually began around Christmas time and they would have to find another means to make a living until they returned – which they always did. They would note this in their log books and we know now that the El Niño would occupier every 7-11 years. Marine and climate scientists noticed that during these El Niño years other species would suffer and the climate would change – the El Niño was not just about fishing. Measurements showed that the current temperatures off of California and Peru warmed during El Niño years from 50 to 80 degrees! The upwelling would stop, the fish would leave, the seals could not feed their young, it rained in places where it normally does not rain, and drought would occur in other parts of the world. Coral reefs would suffer and other global climate changes would occur.

Warm water in the eastern Pacific indicates an El Nino season.

Graphic: NOAA

What they have discovered is that the cold ocean currents from the poles that pass California and Peru typically reach the equator and flow westward towards Indonesia and Australia. As the water moved along the equator it would warm producing the tropical reef world of Southeast Asia and the Great Barrier Reef. But during El Niño years this warm water begins to move eastward – back towards California and Peru. The cause is not fully understood yet. But the dry air of California becomes moist, rain falls, which effects the climate all across the country. One notable event locally is that most of the hurricanes are pushed upwards into the Atlantic and miss the Gulf of Mexico. The El Niño usually last a year. One other note here also. El Niño is typically followed by a year of drastic cooling – the La Niña.

How are the El Niño’s effected by climate change?

Some scientist believe the frequency of El Niño will not change but that the frequency of “super” El Niño’s will – they will increase. “Super” El Niño’s occurred twice in the last 20 years and the impacts on fishing, agriculture, and other human actives have been significant. The over all warming of the oceans will fuel a stronger warming event during an El Niño year. W are currently having the strongest “super” El Niño on record.

We will see what 2016 brings, it will be interesting. I know it is 70 degrees right now (December 28) and there are butterflies in my yard.

http://www.climatecentral.org/news/climate-change-could-make-super-el-ninos-more-likely-16976

by Rick O'Connor | Sep 23, 2015

This area along Florida’s east coast is experiencing coastal flooding.

Photo: University of Florida

As we come towards the end of National Estuaries Week we will now look at some issues our estuaries are facing. Sea level rise is one that generates a variety of responses from the public. For some it is of concern, something we need to be planning for and need to spend more research dollars on to improve our models to understand it. For others, it is a problem for the back burner; yea, it is happening but the changes are over a long period of time and the serious impacts will not occur for a while – and we have more pressing issues to deal with. The old “it’s not a problem until it’s a problem” form of planning. Others still understand it but do not believe the models and do not believe the impacts will be very serious – thus warrants little or no planning. And there are those who do not believe climate change and sea level rise is actually occurring. They see no tangible evidence of any changes. Each year feels like the last – it just is not happening.

A couple of years ago I was part of a team that conducted a series of focus group meetings with residents and businesses who live and work on our barrier islands. The focus of the discussion was to determine what the coastal residents were most concerned about in terms of climate change, sea level rise, and coastal resiliency. The majority of the participants did not deny climate change but were not concerned about planning for it at this time; they had other issues were more pressing… like coastal flooding and the national flood insurance plan – which plans to increase rates for properties in flood prone areas. Ironically, this issue is tied to climate change and sea level rise. They were more concerned about it than they realized. And we did have a few who asked the question – “is there any science that supports the notion of climate change?” Let’s start there… is there any science to support this?

Yes… this link to NASA (http://climate.nasa.gov/evidence/) is a page developed to help the public better understand what the science says about this. Yes, there is evidence that the carbon is increasing in our atmosphere, that global temperatures are rising, as are sea levels. Many are experiencing some of the changes that were discussed in the 1980’s. Some areas are seeing more rain, others more drought. Gardeners in parts of the country are noticing that things they use to do in April, they now do in March. More tropical plants and animals are migrating north – there are at least three records of red and black mangroves growing the Florida panhandle and a snook was caught a couple of years ago at Dauphin Island, Alabama. These subtle changes have been noticed by some. Others, such as those in southeast Florida, have witnessed more direct evidence, such as portions of A1A going underwater during extreme high tides. But there is science to support this.

Islands in the south Pacific who are dealing with the impacts of sea level rise during storm events.

Photo: Greenpeace

What is causing sea level rise?

Well, according to a document published by Florida Sea Grant there are three general causes.

- Temperature – as the atmosphere and oceans warm the water expands thus causing the sea level to rise. This thermal expansion has accounted for about 25% of the sea level rise we have witnessed; between 1993 and 2010 it accounted for 40% of it.

- Ice melt – 60% of the current rise in sea level has been due to the melting of land based ice; such as glaciers.

- Land fall – for a variety of reasons, some coastal land masses have actually dropped; thus forcing the sea level to rise.

What do the current models predict for future sea level rise?

Most of the models are predicting an increase between 1.5 and 4.5 feet, depending on where you are, by 2100.

So what?

Again some coastal communities are experiencing impacts now. South Florida Water Management District is currently replacing all of their gravity flow drains due to the fact that sea level has risen enough that they only work at low tide. Monroe County (Florida Keys) is now replacing their vehicles at a faster rate due to constant driving through salty flood waters. Many Florida coastlines are now experiencing saltwater intrusion of their freshwater supply. This is partially due to the over consumption of that resource but it is also due to sea level rising introducing salt water to these systems. There has been increased flooding in many parts of the country, including the Florida Panhandle.

So what does this mean for our local estuaries?

As we have said, sea level rise has occurred before – will this be a problem for our estuarine habitats? Generally ecosystems adjust to environmental change over time but they cannot respond if these changes occur too fast. Scientists have determined that an increase of 0.13” of sea level/year will flood our coastal marshes and we may lose them; currently the rate is about 0.11”/year. It is believed that our barrier islands will “roll” landward but science is not sure how fast this will happen. There may be changes in species composition within our estuaries – which could be good or bad – and there is certainly room for the expansion of invasive species.

A graphic indicating the potential flooding of Florida.

Graphic: Green Policy 360

How has government responded?

Federal and county governments have responded – the state… not so much. According to Thomas Ruppert (Florida Sea Grant) the local governments have done the best job planning for these future changes. Many areas in the state now require some form of sea level rise planning in all new development projects. At the very least coastal communities should look at future development plans and think long term as to where flooding may become a bigger issue.

“The times they are a changing…”