by Rick O'Connor | Oct 21, 2025

Many who have snorkeled or dove in the Florida Keys have most likely encountered nurse sharks there – they are quite common. But here in the northern Gulf – though present – encounters are not as frequent. In the Keys you can don a mask, swim along a seawall, bridge piling, or over limestone bottom in shallow water and found one – maybe several. In the northern Gulf encounters are more offshore by SCUBA alone, and I would say – still not that common.

All this to say that one was seen off a dock recently in Escambia County inside the bay. It was swimming along the edge of the dock in a seagrass bed searching for something to eat. Again, this would not be abnormal if in south Florida, but a cool event in our area.

Nurse sharks are docile fish recognized by their brownish copper coloration, two large dorsal fins set back on their dorsal side, and barbels extending from their upper jaw similar to catfish. These barbels indicate they are more bottom feeders, and they spend a lot of time lying on the bottom. Though they can reach lengths of 14 feet, nurse sharks are not considered a threat – unless you mess with them – and exciting to see.

They are considered a tropical species – hence the lower number of encounters in our area. They prefer hardbottom – such as coral reefs and limestone shelves – higher salinities, dissolved oxygen levels, and clear water. Over this summer local water temperatures have increased, and the lack of rain has increased salinities across the area. The lower amount of rain has reduced stormwater runoff from land and allowed the water to become clearer. Everything that a nurse shark would want.

As mentioned, encounters with this species are not considered threatening and a very cool memory. We do not know how long the current conditions will last but maybe you too will see one. It would be pretty exciting.

Nurse shark inside bay in Escambia County.

Photo: Angela Guttman

by Rick O'Connor | Sep 22, 2025

Introduction

The diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin) is the only resident turtle within brackish water and estuarine systems in the United States (Fig. 1). They prefer coastal estuarine wetlands – living in salt marshes, mangroves, and seagrass communities. The literature suggests they have strong site fidelity – meaning they do not move far from where they live. Within their habitat they feed on shellfish, mollusk and crustaceans mostly. In early spring they will breed. Gravid females will venture along the shores of the bay seeking a high-dry sandy beach where they will lay a clutch of about 10 eggs. She will typically return to lay more than one clutch each season. Nesting will continue through the summer. Hatching begins mid-summer and will extend into the fall. Hatchings that occur in late fall may overwinter within the nest and emerge the following spring. They live 20-25 years.

Fig. 1. The diamondback terrapin.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

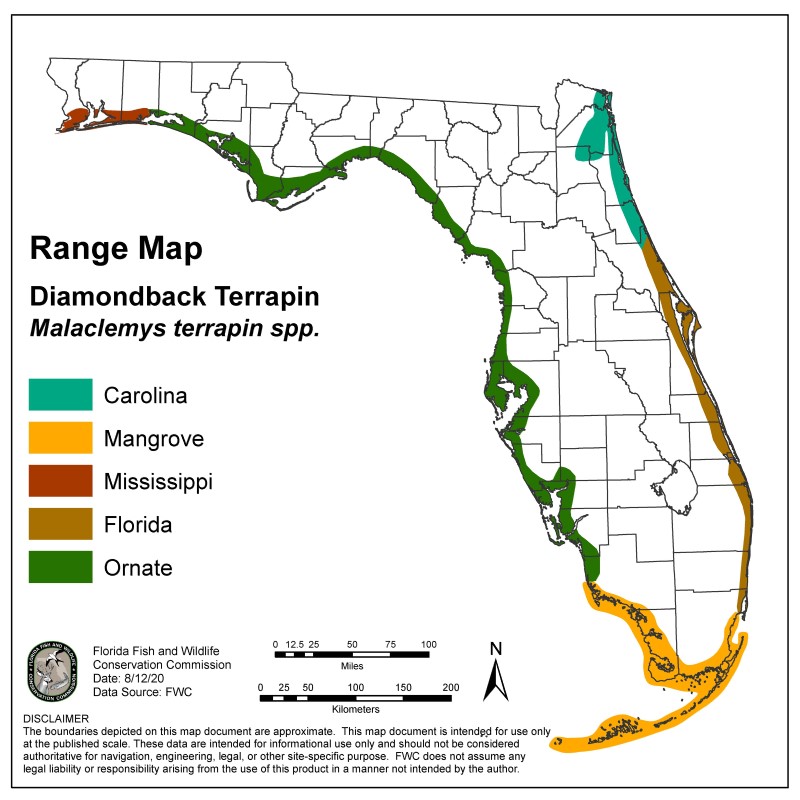

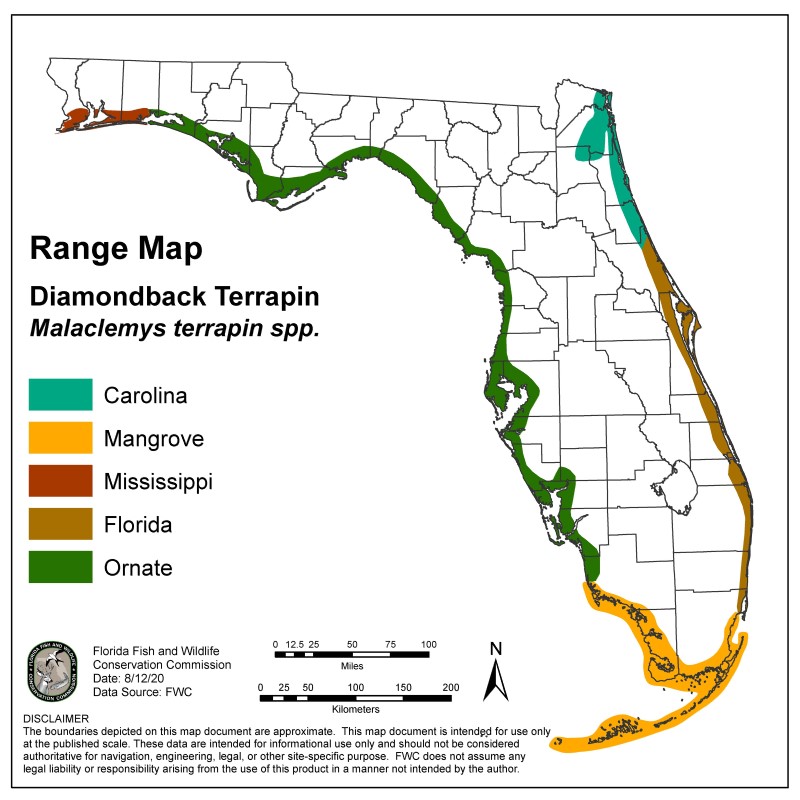

Terrapins range from Massachusetts to Texas and within this range there are currently seven subspecies recognized – five of these live in Florida, and three are only found in Florida (Fig. 2). However, prior to 2005 their existence in the Florida panhandle was undocumented. The Panhandle Terrapin Project (PTP) was initially created to determine if terrapins did exist here.

Fig. 2. Terrapins of Florida.

Image provided by FWC

The Scope of the Project

Phase 1

The project began in 2005 using trained volunteers to survey suitable habitat for presence/absence. Presence is determined by locating potential nesting beaches and searching for evidence of nesting. Nesting begins in April and ends in September – with peak nesting occurring in this area during May and June. The volunteers are trained in March and survey potential beaches from April through July. They search for tracks of nesting females, eggshells of nests that were depredated by predators, and live terrapins – either on the beach or the heads in the water. Often volunteers will conduct 30-minute head counts to determine relative abundance. Between 2005 and 2010 the team was able to verify at least one record in each of the panhandle counties.

Phase 2

The next phase is to determine their status – how many nesting beaches does each county have, and how many terrapins are using them? A suitability map was developed by Dr. Barry Bitters as a Florida Master Naturalist project to locate suitable nesting beaches. Volunteers would visit these during the spring to determine whether nesting was occurring, and the relative abundance was determined using what we called the “Mann Method” – developed by Tom Mann of the Mississippi Department of Wildlife, along with the 30-minute head counts. The Mann Method involved counting the number of tracks and depredated nests within a 16-day window. The assumption to this method was that nesting females would lay multiple clutches each season – but they did not lay more than one every 16 days. Going on another assumption, that the sex ratio within the population was 1:1, each track and depredated nest within a 16-day window was a different female and doubling this number would give the relative abundance of adults in this population. Between 2007 and 2023 we were able to determine the number of nesting beaches in each county and relative abundance in three of those counties (see results below).

Phase 3

Partnering with the U.S. Geological Survey, we were able to move to Phase 3 – which involves trapping and tagging terrapins. Doing this gives the team a better idea of where the terrapins are going and how they are using the habitat. To trap the terrapins, we use modified crab traps (modified so that the terrapins had access to air to breath), seine nets, fyke nets, dip nets, and by hand – the most effective has been modified crab traps (Fig. 3). These traps are placed in terrapin habitat over a 3-day period, being checked daily. Any captured terrapins are measured, weighed, sexed, marked using the notch method, and given a Passive Intergraded Transponder (PIT) tag. Some of the terrapins are given a satellite tag where movement could be tracked by GPS (Fig. 4). We are now bringing on acoustic tagging for some counties. This involves placing acoustic receivers on the bottom of the bay which will detect any terrapin (with an acoustic tag) that swims nearby. Results are below.

Fig. 3. Modified crab traps is one method used to capture adults.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

Fig. 4. This tag with an antenna can be detected by a satellite and tracked real time.

Photo: USGS

Phase 4

This phase involves collecting tissue samples for genetic analysis. Currently it is believed that the Ornate terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin macrospilota) ranges from Key West to Choctawhatchee Bay, and the Mississippi terrapin (M.t. pileata) ranges from Choctawhatchee Bay to the Louisiana/Texas border. The two subspecies look morphologically different (Fig. 5) and the team believes terrapins resembling the ornate terrapin have been found in Pensacola Bay. Researchers in Alabama have also reported terrapins they believe to be ornate terrapins in their waters as well. The project is now working with a graduate student from the University of West Florida who is genetically analyzing tissue samples from trapped terrapins to determine which subspecies they are and what the correct range of these subspecies. This phase began in 2025, and we do not have any results at this time.

Fig. 5. The Mississippi terrapin found in Pensacola Bay is darker in color than the Ornate terrapin found in other bays of the panhandle.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Ornate Diamondback Terrapins Depend on Coastal Marshes and Sea Grass Habitats

Photo: Erik Lovestrand.

2025 UPDATE AND RESULTS

In 2025 we trained 188 volunteers across each county – including state park rangers and members of the Florida Oyster Corps. 47 (25%) participated in at least one survey.

We logged 345 nesting surveys and 17 trap days.

No seining or fyke nets were conducted in 2025.

Phase 1 – Presence/Absence Update

| County |

Presence |

Notes |

| Baldwin |

Yes |

A single deceased terrapin was found in western Baldwin County |

| Escambia |

Yes |

Team encountered nesting again this year |

| Santa Rosa |

Yes |

Two new locations were identified this year |

| Okaloosa |

Yes |

Encounters were lower this year |

| Walton |

Yes |

FIRST EVIDENCE OF NESTING IN WALTON COUNTY VERIFIED THIS YEAR |

| Bay |

Yes |

FIRST EVIDENCE OF NESTING IN BAY COUNTY VERIFIED THIS YEAR |

| Gulf |

Yes |

Team encountered nesting again this year |

| Franklin |

ND |

ND |

Phase 2 Nesting Survey – Update

| County |

# of primary beaches1 |

# of secondary beaches2 |

# of surveys |

# of encounters |

FOE3 |

| Baldwin |

0 |

TBD |

14 |

04 |

.00 |

| Escambia |

2 |

35 |

99 |

7 |

.07 |

| Santa Rosa |

3 |

45 |

137 |

25 |

.18 |

| Okaloosa |

4 |

3 |

20 |

1 |

.05 |

| Walton |

1 |

4 |

28 |

2 |

.07 |

| Bay |

3 |

3 |

47 |

14 |

.30 |

| TOTAL |

13 |

17 |

345 |

49 |

.14 |

1 primary beaches are defined as those where nesting is known to occur.

2 secondary beaches are defined as those where potential nesting is high but has not been confirmed.

3 FOE (Frequency of Encounters) is the number of terrapin encounters / the number of surveys conducted.

4 There was one deceased terrapin found by a tour guide in Baldwin County but was not part of the project.

5 There are potential nesting sites on Pensacola Beach that are technically in Escambia County but covered by the Santa Rosa team. The Escambia team focused on the Perdido Key area.

Phase 3 Trapping/Tagging Update

We currently have 8 years of data.

Terrapins have been tagged in 7 of the 8 panhandle counties.

1483 captures, 1061 individuals.

2025 Capture Effort

| Method |

County |

Number |

Description |

Condition |

| Hand capture |

Escambia |

1 |

1 adult male |

Deceased |

| Hand capture |

Santa Rosa |

5 |

4 adult females

1 unknown |

Released, deceased |

| Hand capture |

Okaloosa |

1 |

1 adult female |

Released |

| Dip Net |

Santa Rosa |

1 |

1 adult male |

Released |

| Crab Traps |

Santa Rosa |

34 |

4 juvenile females

5 adult females

25 adult males |

Released |

|

Okaloosa |

4 |

1 juvenile female

3 adult males |

Released |

| TOTAL |

|

46 |

5 juvenile females

10 adult females

30 adult males

1 unknown |

|

Preliminary information subject to revision. Not for citation or distribution.

Satellite Tagging Information

Due to the size of the tags – only large females are satellite tagged at this time.

Big Momma – tracked for 188 days – averaged 0.16 miles.

Big Bertha – tracked for 137 days – averaged 35.83 miles.

2025 Tracking Effort

| County |

Tagging Effort |

| Santa Rosa |

2 satellite tagged

6 acoustically tagged |

| Okaloosa |

1 satellite tagged |

| TOTAL |

8 tagged for tracking |

Phase 4 Update

This phase began in 2025 and there are no results at this time.

Summary

2025

17 trainings were given in 7 of the 8 counties of the Florida panhandle (including Baldwin County AL).

188 were trained; 47 (25%) conducted at least one survey.

345 surveys were logged; terrapins (or terrapin sign) were encountered 49 (14%) of those surveys.

Every county had at least one encounter during a nesting survey.

17 trapping days were conducted; 46 terrapins were captured; 37 (83%) were captured in modified crab traps; 7 were captured by hand; 1 was captured in a dip net.

8 terrapins were tagged for tracking; 6 acoustically; 2 with satellite tags.

Since 2007

511 have been trained.

1449 surveys have been logged; 347 encounters have occurred; Frequency of Encounters is 24% of the surveys.

Discussion

Phase 1

We have shown that diamondback terrapins do exist in the Florida panhandle and in Baldwin County AL.

Phase 2

We currently have 13 primary nesting beaches we are surveying weekly during nesting season across the panhandle. There were 17 secondary nesting beaches surveyed and most likely there are many more to visit. Nesting seems to be more common in late spring, but the Frequency of Encounters has been declining since 2023. This could be due to less terrapin activity but could also be due to evidence being difficult to find. We will continue to monitor to see how this trend continues.

Phase 3

The team has captured 1483 terrapins, the majority of which were from the eastern panhandle. Satellite tagged females suggest more than one has traveled over 30 miles from where they were tagged. This goes against the idea that terrapins have strong site fidelity. However, all the terrapins tagged were large females (due to size of the tags) so we are looking at the movements of only the larger females – not the population as a whole. The movements of these females also suggest they may use seagrass beds as much as the salt marshes.

Training for volunteers occurs in March of each year. If you are interested in participating, contact Rick O’Connor – roc1@ufl.edu.

by Rick O'Connor | Jun 20, 2025

Snails and slugs belong to one of the largest phyla of animals on the planet – the mollusks. Mollusks are known for their calcium carbonate shells and seashell collecting along the shoreline has been a popular hobby for centuries. There are an estimated 50,000 to 200,000 species of mollusk worldwide. One group – the gastropods – have an estimated 40,000 to 100,000 species alone. This is the group that includes the snails and slugs.

Snails are soft-bodied creatures who produce a single, usually coiled, shell in which they live. The coiled shell has an opening called the aperture through which they can extend some, or most of their body. The elongated soft body “slugs” across the sea bottom searching for food which could be vegetation for some – like the small nerite snails found in our bays, or animals – like the venomous cone snails, or detritivores – like the periwinkle snails.

The Olive Nerite.

Photo: Wikipedia.

Many species of local snails produce egg cases in which they deposit their developing eggs. These are often found while people are beach combing. The most frequently encountered locally are the tube-shaped clusters of the oyster drill, the coin shaped chain of the lightning whelk, and the one that – to me – resembles the top of a vase or jar belonging to the moon snail.

The egg case of the Lightning Whelk.

Photo: Project Noah

The variety of snails found in the northern Gulf is immense – so, we will cover only a few of the more common.

Walking along the Gulf side, gazing down at the shells of snails washed ashore, one often finds the small ceriths. These tiny, elongated shells are small and look like a canine tooth. These are herbivores and detritivores.

Cerith

Photo: iNaturalist

The Florida Fighting Conch is often found – but not always in whole condition. This is a true conch and herbivorous.

Florida Fighting Conch

Photo: iNaturalist

One not as common while beachcombing, but more common while snorkeling is the olive snail. These are fast burrowing snails that feed on bivalves and carrion they may find. I often find trails crisscrossing the sandy bottom made by these snails just off the beach.

Olive snail

Photo: Flickr

Over on the bay side of the barrier islands you have a better chance of finding live snails. One of the more common in the salt marshes is the marsh periwinkle. This small roundish snail is often seen on the extended leaves of the marsh grasses. It is here during high tide to avoid predators such as blue crabs and diamondback terrapins. At low tide they will descend to the muddy bottom and feed on detritus.

The marsh periwinkle is one of the more common mollusk found in our salt marsh. Photo: Rick O’Connor

The crown conch is another frequently seen estuarine snail. With spines extending from the top whorl – it appears to have a crown, and where its common name comes from. These are predators of the bay feeding on other mollusks such as periwinkles and oysters.

The white spines along the whorl give this snail its common name – crown conch.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

The oyster drill shell is one of the more common shells you find hermit crabs in, but the snails are out there as well. As the name implies, they use a tooth like structure called a radula to bore into other mollusk shells to feed. They are particularly problematic for non-moving oysters – and where they got their common name from.

The shell of the oyster drill.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

The only slug I have encountered on our beaches is the sea hare. These slugs can be a greenish or brownish color and are about six inches in length. They lack an external shell but do not move much faster than their snail cousins. They feed on a variety of seaweeds and the color of their skin mimics the seaweeds they are feeding on. Lacking a shell, they produce a toxin in their skin to repel would be predators. They also release ink like the squid and octopus cousins.

A common sea slug found along panhandle beaches – the sea hare.

This narrative only scratches the surface of the world of snails and slugs in this part of the world. Creating a check list of species and then seeing if you can find them all is great fun.

References

The Mollusca. Sea Slugs, Squids, Snails, and Scallops. University of California at Berkley. https://ucmp.berkeley.edu/taxa/inverts/mollusca/mollusca.php#:~:text=Mollusca%20is%20one%20of%20the,scallops%2C%20oysters%2C%20and%20chitons..

Gastropods. University of Texas San Antonio. https://www.utsa.edu/fieldscience/gastropod_info.htm#:~:text=Gastropods%20are%20another%20type%20of,of%20the%20entire%20Mollusca%20phylum..

by Rick O'Connor | May 16, 2025

As far as familiarity goes – everyone knows about worms. As far as seeing them – these are rarely, if ever seen by visitors to the northern Gulf. Most know worms as creatures that live beneath the sand – out of sight and doing what worms do. We imagine – scanning the landscape of the Gulf – millions of worms buried beneath the sediment. For some this may be quite unnerving. Worms are sometimes “gross” and associated with an unhealthy situation. You might say to your kids “don’t dig in the sand – you might get worms”. Or even “don’t drink the water – you might get worms”. But the reality of it all is that there are many kinds of worms in the northern Gulf, and many are very beneficial to the system. We will look at a few.

The common earthworm.

Photo: University of Wisconsin Madison

Flatworms are the most primitive of the group. As the name implies, they are flat. There is a head end, often with small eyespots that can detect light, but the mouth is in the middle of the body and, like the jellyfish, is the only opening for eating and going to the restroom. There are numerous species of flatworms that crawl over the ocean floor feeding on decayed detritus, many are brightly colored to advertise the fact they are poisonous – or pretending to be poisonous. And then there are species that actually swim – undulating through the water in a pattern similar to what we do with our hand when we stick it out the window driving at high speed.

But there are parasitic flatworms as well. Worms such as the tapeworm and the flukes are more well known than the free-swimming flatworms just described. These are the worms people become concerned about when they hear “there are worms out there”. And yes – they do exist in the northern Gulf. But what some people may not realize is that these internal parasites are adapted for the internal environment of their selected host and cannot survive in other creatures. There are human tapeworms and flukes, but they are not found in the sands of the Gulf.

The human liver fluke. One of the trematode flatworms that are parasitic.

Photo: University of Pennsylvania

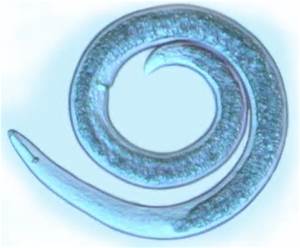

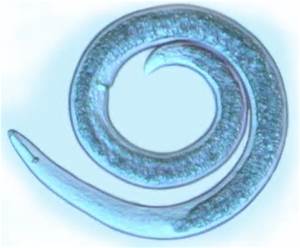

As the name implies, roundworms are round – but they differ from earthworms in that their bodies are smooth and not segmented as earthworms are. One group of roundworms is well known in the agriculture and horticulture world – nematodes. Some nematodes are also known for being human parasites – again, creating some concern. These include the hookworm and pinworm. Roundworms can be found in the sediments by the thousands – sometimes in the millions. The abundance of some species are used as an indicator of the health of the system – the more of these particular type of roundworms, the more unhealthy the system – again, a cause of concern for some when they see any worm in the sand.

The round body of a microscopic nematode.

Photo: University of Nebraska at Lincoln

We will end with the segmented worms – the annelids. This is the group in which the familiar earthworm belongs. Though earthworms do not exist in the northern Gulf, their cousins – the polychaetae worms – are very common. Polychaetas are much larger, easier to see, and differ from earthworms in that they have extended legs from each segment called parapodia. Some polychaetas produce tubes in which they live. They will extend their antenna out to collect food. Many of these tubeworms have their tubes beneath the sand and we only see them (rarely) when their tentacles are extended – or when they extend a gelatinous mass from their tubes to collect food. But there is a type of tubeworm – the sepurlid worms – that produce small skinny calcium carbonate tubes on the sides of rocks on rock jetties, pier pilings, and even marine debris left in the water. This is also the group that the leech belongs to. Though leeches are more associated with freshwater, there are marine leeches. These are rarely encountered and do not attach to humans as their freshwater cousins do.

Diopatra are segmented worms similar to earthworms who build tubes to live in. These tubes are often found washed up on the beach.

Though we may be “creeped-out” about the presence of worms in the northern Gulf of Mexico, they are none threatening to us and are an important member of the marine community cleaning decaying creatures and waste material from the environment. We know they are there, and glad they are there.

by Rick O'Connor | May 12, 2025

When I began working with terrapins 20 years ago, very few people in the Florida panhandle knew what they were – unless they had moved here from the Mid-Atlantic states. Since we initiated the Panhandle Terrapin Project in 2005 many more now have heard of this brackish water turtle.

Ornate Diamondback Terrapin (photo: Dr. John Himes)

Diamondback terrapins are relatively small (10 inch) turtles that inhabit brackish environments such as salt marshes along our bays, bayous, and lagoons. They have light colored skin, often white, and raised concentric rings on the scales of their shells which give them a “diamond-backed” appearance. Some of them have dark shells, others will have orange spots on their shells.

The first objective for the project was to determine whether terrapins existed here, there was no scientific literature that suggested they did. We found our first terrapin in 2007, and this was in Santa Rosa County. We have since had at least one verified record in every panhandle county – diamondback terrapins do exist here.

The second objective was to locate their nesting beaches. Terrapins live in coastal wetlands but need high-dry sandy beaches to lay their eggs. Volunteers began searching for such and have been able to locate nesting beaches in Escambia, Santa Rosa, Okaloosa, Bay, and Gulf counties. We continue to search in the other counties, and for additional ones in the counties mentioned above. Once a nesting beach has been identified, volunteers conduct weekly nesting surveys, providing data which can help calculate the relative abundance of terrapins in the area.

Tracks of a diamondback terrapin.

Photo: Terry Taylor

The third objective is to tag captured terrapins to determine their population, where they move and how they use habitat. We initially captured terrapins using modified traps and marking them using a file notching system. We then partnered with a research team from the U.S. Geological Survey and now include passive integrated transponder tags (PIT tags) that help identify individuals, satellite tags that can be detected from satellites and track their movements, and recently acoustic tags which can also track movement.

The fourth objective is to collect tissue samples for genetic studies. This information will be used to help determine which subspecies of terrapins are living in the Florida panhandle.

As we move into the summer season, more people will be recreating in our bays and coastal waterways. If you happen to see a terrapin, or maybe small turtle tracks on the beach, we would like you to contact us and let us know. You can contact me at roc1@ufl.edu. Terrapins are protected in Florida and Alabama, so you are not allowed to keep them. If you are interested in joining our volunteer team, contact me at the email address provided.

by Rick O'Connor | May 2, 2025

Many of the creatures we have written about in this series to this point are ones that very few people have ever heard of. But that is not the case with jellyfish. Everyone knows about jellyfish – and for the most part, we do not like them. These are the gelatinous blobs with trailing tentacles filled with stinging cells that cause pain and trigger the posting of the purple warning flags at the beach. They are creatures that many place in the same class as mosquitos and venomous snakes – why do such creatures even exist. But exist they do and there are plenty in the northern Gulf – more than you might be aware of.

Jellyfish are common on both sides of the island. This one has washed ashore on Santa Rosa Sound.

The ones we are familiar with are those that are gelatinous blobs with trailing tentacles – called medusa jellyfish. These include the common sea nettle (Chrysaora). Sea nettles have bells about 4-8 inches in diameter (though they are larger offshore). The bell has extended triangle markings that appear red and tentacles that can extend several feet beneath/behind the bell. The tentacles are armed with nematocyst – cells that contain a coiled “harpoon” which has a drop of venom at the tip. They use these nematocyst to kill their prey – which include small fish, zooplankton, and comb jellies. But they are also triggered when humans bump into them producing a painful sting. Their prey is digested in a sack-like stomach called the gastrovascular cavity and waste is expelled through their mouth, because they lack an anus. Though these animals can undulate their bells and swim, they are not strong enough to swim against currents and tides – and thus are more planktonic in nature.

Another familiar jellyfish is the moon jelly (Aurelia). These are the larger, saucer shaped jellyfish that resemble a pizza with a clover leaf looking structure in the middle. They can reach 24 inches in diameter across the bell which is often seen undulating trying to swim against the current and tide. Their tentacles are very short – extending from the rim of the bell – but there are four large oral arms that are quite noticeable. The oral arms also possess nematocyst for killing prey. Their prey includes mostly zooplankton and other jellyfish. Like their cousins the sea nettles, moon jellies are planktonic in nature and are often found washed ashore during high energy days. Some say the pain from this jellyfish is minimal, others feel a lot of pain.

The remnants of moon jellyfish near a ghost crab hole.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Though there are many others, our final familiar jellyfish would be the Portuguese man-of-war (Physalia). If you have never seen one, you most likely have heard of them. These are easy to identify. They produce a bluish colored gas filled balloon like sack that floats on the surface and extends above water to act as a “sail”. This gas filled sack is called a pneumatophore and helps move the animal across the Gulf. Extending down from this pneumatophore are numerous purple to blue to clear colored tentacles. You would think the pneumatophore would be the bell of the jellyfish and the tentacles of similar design as to the ones we mentioned above – but that would be incorrect. The tentacles are actually a colony of small polyp jellyfish connected together – it is not a true jellyfish (as we think of them). The stomachs of these individual polyps are connected and as one kills and feeds, the food passes throughout the colony to nourish all. In order to feed the whole colony, you need larger prey. To kill larger prey, you need a more toxic venom, and PMOW do have a very strong toxin. The sting from this animal is quite painful – though rare, it has even killed people. This jellyfish should be avoided. As with other jellyfish, they often wash ashore, and their stinging cells can still be triggered. Do not pick them up.

There is another form of jellyfish found here that is not as well known. They may be known by name, but not as jellyfish. They are called polyp jellyfish and instead of having an undulating bell with tentacles drifting behind, they are attached to the seafloor (or some other structure) and extend their tentacles upward. They look more like flowers and do not move much. Examples of such jellyfish include the tiny hydra, sea anemones, and corals. As with their medusa cousins, they do have nematocysts in their tentacles and can provide a painful sting, though some produce a mild toxin, and the sting is not as painful as other jellyfish. Many of these polyp jellyfish are associated with coral reefs. Though coral reefs are common in tropical waters, they do occur to a lesser extent in the northern Gulf.

The polyp known as Hydra.

Photo: Harvard University.

We will complete this article with a group of jellyfish that do not have nematocysts and, thus, do not sting – the comb jellies. Though many species of comb jellies have trailing tentacles, the local species do not. When I was young, we called them “football jellyfish” because of their shape – and the fact that you could pick them up and throw them to your friends. I have also heard them called “sea walnuts” because of their shape. A close look at this jellyfish you will see eight grooves running down its body. These grooves are filled with a row of cilia, small hairlike structures that can be moved to generate swimming. The cilia move in a way that they resemble the bristles of a comb we use for combing our hair. You have probably taken your thumb and run it down your comb to see the bristles bend down and back into position – sort of like watching the New York Rockettes high kick from one end of their line to the other – this is what the cilia look like when they are moving within these grooves – and give the animal its common name “comb jelly”. Since they do not have nematocysts, they are in a different phylum than the common jellyfish. They feed on plankton and each other and can produce light – bioluminescence – at night.

Though not loved by swimmers in the northern Gulf, jellyfish are interesting creatures and beautiful to watch in public aquaria. They have their bright side.

Comb jellies do not sting and they produce a beautiful light show at night.

References

Atlantic Sea Nettle. Aquarium of the Pacific. https://www.aquariumofpacific.org/onlinelearningcenter/species/atlantic_sea_nettle1.

Moon Jellyfish. Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. https://www.aquariumofpacific.org/onlinelearningcenter/species/atlantic_sea_nettle1.