by Rick O'Connor | Apr 1, 2022

In December of 2021 the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) passed new regulations concerning the diamondback terrapin. One will make it illegal to possess a terrapin without a permit beginning March 1, 2022. The other will impact recreational crab trap design in early 2023. A number of people have begun to ask questions ab

The diamond in the marsh. The diamondback terrapin.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

ut this new ruling so, we will explain it.

WHAT IS A DIAMONDBACK TERRAPIN?

We will start there. Most Floridians have never heard of this animal, and if they have, they know it from the Chesapeake Bay area. Diamondback terrapins are turtles in the Family Emydidae. This family includes many of the pond turtles Floridians are familiar with – cooters, sliders, red-belly, and others. The big difference between terrapins and pond turtles is the coloration of their skin, and their preference for brackish water – they like estuaries over ponds and lakes. They do have lachrymal glands in their eyes to help excrete salt from water, but they are not as efficient as those of sea turtles so, they cannot live in sea water for more than about a month – it is the bays and bayous they like to call home.

There are seven recognized subspecies which range from Cape Cod MA., to Brownsville TX. Five of them are found in Florida and three are only found in Florida. But few Floridians have ever heard of them and even fewer have seen one. Their cousins the pond turtles are quite common. We see their heads in ponds and lakes, several of them basking on logs near shore of ponds, lakes, and rivers, and frequently see dead ones along our highways. We don’t see terrapins. We do not see their heads in the marsh, basking on logs, or dead carcasses along our coastal highways. Again, this is an unknown turtle to us.

WHY ARE THERE NEW REGULATIONS ON A TURTLE MANY HAVE NEVER SEEN?

The question sort of explains the answer – we do not see them – their population in our state may deem some action by the FWC. In the Chesapeake region they are quite common, and people see them frequently. It is the mascot of the University of Maryland. Along the roads to the barrier islands in Georgia hundreds of terrapins can be found trying to nest and many are hit by cars. In most of these mid-Atlantic states there is some form of protection for them. They either list them as threatened or a species of concern. One state has it listed as endangered. Again, these are states where encounters are much more common.

Florida has a rich diversity of turtles, maybe the richest in the country, and we have been the target for turtle harvest. Turtles are sought after for food and as pets. The harvest of some species has been heavy and FWC has listed them as “no take”. For a variety of reasons, harvest being one of them, Alligator Snapping Turtles (Macrochelys temminckii), the Suwannee Cooter (Pseudemys suwanniensis), and the Barbour’s Map Turtle (Graptemys barbouri) are illegal to possess without a permit. This includes their eggs. Because other species look very similar to these, they have also been added to the no-take list. This would include all species of cooters and snapping turtles, the Escambia Map Turtle (Graptemys ernsti) and the Striped Mud Turtle (Kinosternon baurii) – which is a small riverine turtle that resembles a small snapping turtle. Note: the regulation on the striped mud turtle is for the lower Florida Keys only. You could take diamondback terrapins but only one and you could have no more than two in your possession. You could not possess their eggs. But with the 2021 ruling – this has changed.

As mentioned, terrapin encounters are rare in our state. There has been concern about their population status here. I got involved with them in 2005 primarily to answer the question “Do terrapins even exist in the Florida panhandle?”. The answer is yes, they do. Since 2005 myself, and trained volunteers, have conducted 859 surveys searching for them between Escambia and Franklin counties. We have encountered terrapins, or terrapin sign (tracks, shells, depredated nests) 215 of those – 25% of the surveys; most of those encounters were terrapin sign – they are hard creatures to find. Because of the low encounter rate across the state, it is believed that the populations here are low and in need for conservation measures.

Then comes the crab traps…

Researchers with the Diamondback Terrapin Working Group have identified several stressors to terrapin populations. Loss of habitat, depredated nests by predators (particularly the raccoon), road mortality, and… crab traps. Terrapins feed primarily on shellfish but will eat other things if given the opportunity. They do have a tendency to enter crab traps. Though they feed on small juvenile crabs it is the bait we think they are after in this scenario. Once in, like blue crabs, they find it hard to escape. Unlike blue crabs, turtles have lungs, and the terrapins eventually drown. In the Chesapeake Bay region blue crabs are ”king” – a major commercial and recreational fishery. Terrapins entering crab traps means crabs are not. There have been as many as 40 dead terrapins found in one trap. This was a major concern for all. Dr. Roger Woods of the Wetlands Institute in New Jersey began working on a device that would keep terrapins out but allow blue crabs in. Data shows that in most cases, the larger females are the ones entering and the smaller males would follow. If you could keep the female out it was believed that most males would not enter. So, the device was designed to keep the large females out. A 6×2” rectangle seemed to work best. Field studies showed that these By-Catch Reduction Devices (BRDs) kept 80-90% of the terrapins out and did not significantly impact the crab catch. We had a design that seemed to work.

This orange plastic rectangle is a Bycatch Reduction Device (BRD) used to keep terrapins out of crab traps – but not crabs.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

BRDs are designed to keep terrapins out but allow crabs to enter.

Photo: Virginia Sea Grant

These BRDs have been required in the Mid-Atlantic states for a few years now. With the concern in Florida populations, it is now coming to Florida. By March 1, 2023, all recreational crab traps in Florida will be required to have a fixed funnel size no larger than 6×2”. Either the funnel must be this size, or you can attach one of the plastic orange BRDs to the opening (see photo). Currently bait and tackle shops do not have the BRDs but will be acquiring over the next year. FWC will be working on providing sources between now and March of 2023. If you are in the Pensacola area you can contact me, I have a case of them in my office.

As far as having one on your possession – it is now a no-take species. This rule began March 1, 2022. If you have had a terrapin in your possession you can apply for a no-cost permit to keep it (visit the FWC link below to obtain information on applying for this permit). If you are an education facility that houses terrapins for educational purposes – the same, you can apply for a no-cost education permit to keep your terrapins. You must have this permit by May 31, 2022.

If you have any questions concerning this ruling or how to comply with it, you can contact FWC or your county Sea Grant Extension Agent. The FWC link for more information on this, and other turtle regulations, can be found at https://myfwc.com/wildlifehabitats/wildlife/freshwater-turtles/?redirect=freshwaterturtles&utm_content=&utm_medium=email&utm_name=&utm_source=govdelivery&utm_term=campaign.

by Rick O'Connor | Mar 24, 2022

When exploring local coastal environments, the salt marsh is one not frequently visited by residents. When first seen, the large field of grass appears inviting. But when you reach it appears impenetrable, full of bugs and snakes, and there must be an easier way around.

The Salt Marsh – the land of the wet and Muddy

Photo: Molly O’Connor

There are three ways to access a salt marsh. One, to just begin walking into the field of grass, pushing your way through like a boat on the ocean. Second, using a trail cut but someone else, that meanders its way to the high ground or open water. And third, from the open water following a creek. This can be done on foot or by a paddle craft.

Entering the salt marsh can be tricky.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

If entering by foot into the field of grass, the explorer is first met with a tall grass with a pointed end – black needlerush. This rather stiff, thin, cylinder-shaped grass has a good name, the pointed end is sharp and hurts as you begin to move it out of the way with your forearms. When in college I was told “you might want to wear jeans”. I did not see wearing jeans in the summer heat as a good idea so, chose not to, but understood quickly why they recommended it. Honestly, I am not sure it would have helped anyway. Needlerush pokes your arms, legs, and care must be taken and avoid bending over to pick something up, else you will get a poke in the face or eye.

Black Needlerush is one of the two dominant plants of our salt marshes. Photo: Rick O’Connor

After quickly meeting black needlerush you meet the mud. They do not call it the land of the wet and muddy for nothing. They mud is like pudding and some sections feel like there is no solid ground. This mud is a slate gray color, smells like rotten eggs, and you can sink into it up to your knees in places. Shoe selection in a place like this is important. Many an explorer has placed their shoe covered foot into the mud only to bring up a shoeless foot the next step. Shoes that can tied or synched to the foot are best. They need a good thick bottom to protect the foot from shells, like oysters. I will tell you “crocs” are not what you want.

The sediment in a marsh is not always as solid as it looks.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

The rotten egg smell is the gas hydrogen sulfide, produced by bacteria breaking down organic material trapped within the marsh. And much becomes trapped here. By definition a marsh is a wetland that is dominated by grasses rather than trees. Being a wetland, it is low in elevation and holds water either from rainwater run-off or from the incoming tide. As the water recedes, leaf litter, animal carcasses, and other debris become trapped in the marsh. In fact, the ability of the marsh to hold this decaying layer of mud plays an important role in keeping the open water clear.

As you labor your way across the marsh, pulling each footstep through the mud while moving the sharp grass, you may see signs of life. Most animals have trouble walking through the grass and mud as well and choose another route. But the density and biomass of the open marsh is impressive. Trying to count the blades of grass would be like trying to count the stars in the sky. It is a very biologically productive place. One creature you may encounter is the bird known as the clapper rail. This brownish bird blends in well in the sea of grass and often builds their nest here. When you come upon them, they will let out a loud squawking sound that will honestly terrify you at first. Sometimes they fly, sometimes they move to a new location, sometimes they hold their position and continue to try and scare you away.

The marsh periwinkle is one of the more common mollusk found in our salt marsh. Photo: Rick O’Connor

Another common creature seen is the marsh periwinkle. This small white snail is often seen on the blades of needlerush. As the tides rises, so does the periwinkle, crawling up the grass to avoid predators like the blue crab and diamondback terrapin. At low tide they are on the surface of the organic mud feeding on bits of decaying material. Again, caution if you are going to bend over to look for them. You may get a needlerush in the eye!

There are times as you are crossing you will come to an open area with little or no grass. These are known as salt pans and are areas with lower elevation that the surrounding marsh. Saltwater lies here during high tide and low. As the pool of water evaporates the salinity of the remaining water increases and becomes too salty for most plants to grow. It becomes a “dead zone” within the marsh. There are a few salt tolerant plants that do grow here. You may see the tracks of other creatures exploring, like raccoons, but otherwise it is a break for you from the constant shoving of needlerush and you step in there.

Occasionally you will cross the opposite in elevation. A high ridge of quartz sand where small shrubs like salt bush or even a small oak can be found. These little oasis’s can be places where other travelers of the marsh will rest. Fiddler crabs, cactus, and maybe even a basking snake could be found here.

A finger of a salt marsh on Santa Rosa Island. The water here is saline, particularly during high tide. Photo: Rick O’Connor

There are times when you will cross a creek. These creeks meander their way through the marsh and to the open water. Many travelers, for obvious reasons, choose to follow these routes. Some creeks are shallow and full of mud where you may sink above your knee. Others are a bit deeper and have more solid bottoms of sand. Walking through the water can give some relief from the needlerush. Here you will see several species of fish. Most are killifish or mullet, but as you get closer to the open water you might find redfish or flounder. It is much easier to see the periwinkles here. You will also notice the ribbed mussels anchored near the base of the needlerush. There are oyster clumps scattered here and there and huge colonies of fiddler crabs. The creeks are good hunting grounds for the stilted legged birds such as the great blue heron and American egret. Clapper rails often nest along the creek edges and there is a lot of sign of raccoons and sometimes otters.

The “snorkel” is called a siphon and is used by the snail to draw water into the mantle cavity. Here it can extract oxygen and detect the scent of prey.

Photo: Franklin County Extension

The crown conch is a frequent visitor to the creeks. This predatory snail moves slowly across the sand and mud seeking other mollusks to feed on. Often you will find their shells not inhabited by them but rather the striped hermit crab, a scavenger in this world.

The nonvenomous Gulf Salt marsh Snake.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

Many fear the marsh due to its reptile community. Over the years of leading hikes here I have heard “are there any snakes here?”. There is only one resident of the salt marsh – the Gulf salt marsh snake. This is a nonvenomous member of the watersnake group known as Neroidia and are more nocturnal in habit. That said, the venomous cottonmouth has been seen here. They are most often seen on one of the high sandy banks, coiled and waiting for potential prey to swim by.

Alligator

Photo: Molly O’Connor

Alligators will venture into salt marshes, but I have only seen few in my years of exploring them in the Pensacola area. They tend to be afraid of people and want to avoid us. Once I saw one in a sandy area before I entered the marsh. It was pointing left with one foot off the ground and not moving – it was frozen in space. I had learned that animals tend to go through what I call the “3 Fs” when they detect a predator. Freeze – Flight – Fight. This one was at F1 – freeze. It thought I was a predator and just as well. If I tried to approach it, theoretically it would have moved to F2 – flight, and would have made a hasty escape. But I chose not to test that.

Mississippi Diamondback Terrapin (photo: Molly O’Connor)

There is a resident turtle here known as the diamondback terrapin. However, it is very elusive and difficult to find. It is the only resident brackish water turtle in North America. Though I have seen terrapins in the water, and more rarely on the beach, I do find evidence of their presence by tracks on the beach and nests that have been predated by raccoons. I did once see one basking on a log.

Smooth cordgrass

Photo: FDEP

If you follow the creek, you will eventually reach open water. Here the marsh converts from a sea of black needlerush to a zone of shorter, greener, more flexible smooth cordgrass. The cordgrass is home to many of the creatures we have mentioned. Killifish, crabs, and snails are abundant. The silt birds frequently this zone hunting for their prey, and you might find additional clams and snails. You might find more open water species as well, like gulls, sand pipers and plovers, and maybe a horseshoe crab.

Though the road is tough, the experience is unique and worth the trip. Many prefer to enter the marsh using a known trail or a paddle craft in the creek. There is a lot less needlerush to poke and mud to sink in doing it this way. However you visit, it is an amazing place. The land of the wet and muddy.

by Rick O'Connor | Mar 24, 2022

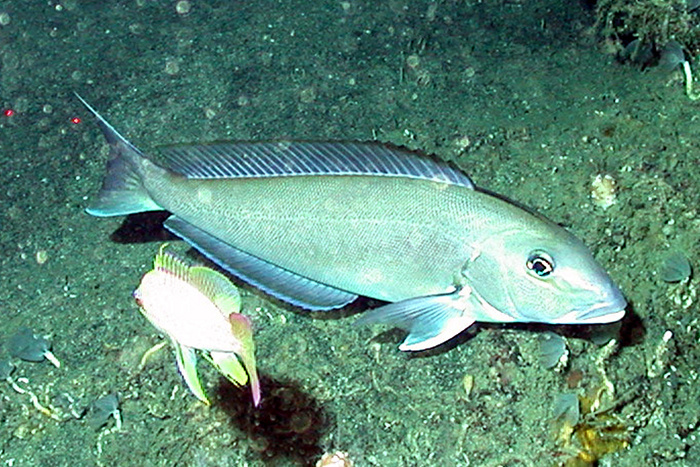

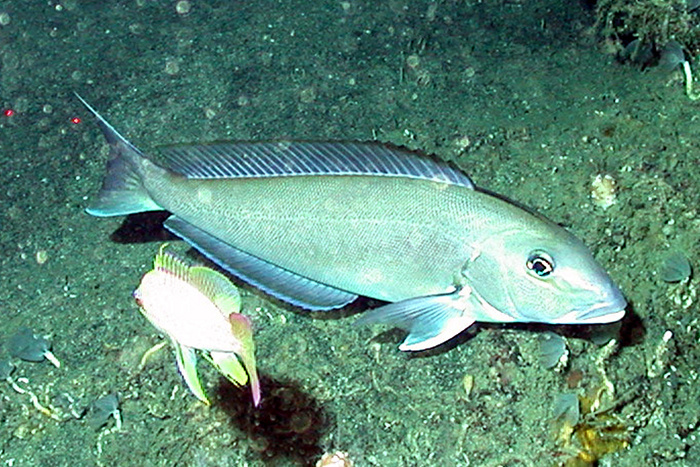

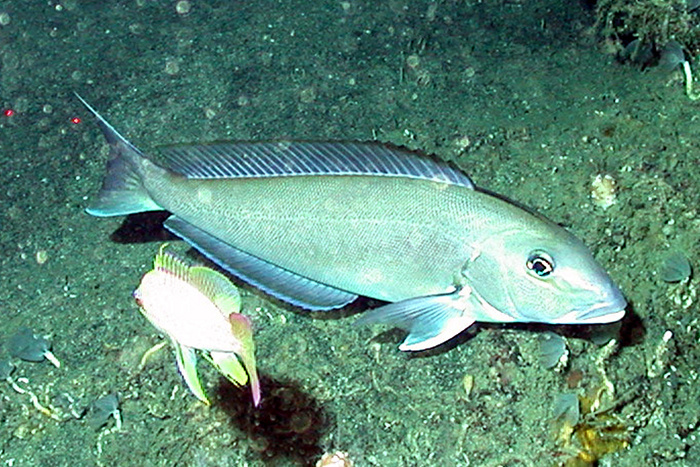

I am going to be honest and say that I know very little about this fish. I did not know they even existed until I attended college. Shortly afterwards, my father-in-law asked “hey, have you ever heard of a tilefish?” – to which I responded yes… He was having lunch at a restaurant in Apalachicola, and it was on the menu. My father-in-law was an avid fisherman and knew most of the edible species, but he had not heard of this one. The rumor was that it was pretty good, though my father-in-law chose not to eat it that day.

Tilefish

Photo: NOAA

I have never seen it on a menu, and only a few times in the local seafood markets, but according to Hoese and Moore1 by the late 1970s there was a small commercial fishery for this fish emerging in Louisiana, as was a small recreational fishery. In Florida, since 2000, there have been 15,435 commercial trips for this fish with an average of 321 each year. The value of this fishery over that time is $33,118,554 with an average of $689,969.90 each year. The average price for the fishermen was $2.62 per pound with the highest being $5.14/lb. on the east coast and that in 2022; the Gulf fishermen are getting $4.16/lb. right now.

The highest number of landings per county since 2000 was 340 in Palm Beach County in 2000. Only eight times has there been more than 200 landings in a single year over the last 22 years. Five of those were in Monroe County (Florida Keys) and three were again in Palm Beach County. The vast majority were less than 100 landings in a single year, this is not a large fishery in Florida either.

Are they harvested here in the Florida panhandle?

Yes… Bay, Escambia, Franklin, Okaloosa, Wakulla, and Gulf Counties all reported landings. Bay County seems to be the hot spot for panhandle with landings between 50-100 each year since 2000. Most of the other counties report less than 10 a year and several only reported one. Again, this is not a large fishery, but it was sold at a restaurant in Apalachicola and is said to be good. Hence, I decided to include in this series.

Hoese and Moore report four species of tilefish in the Gulf of Mexico. The sand tilefish (Malacanthus plumeri) is a more tropical species. The tilefish (Lopholatilus cheamaeleonticeps) and the gray tilefish (Caulalatilus microps) seem to be the target ones for fishermen. Both are reported from deep cold water near the edge of the continental shelf. FWC reports them from 250 – 1500 feet of water where the temperatures are between 50 – 60°F. Because of their tolerance to cold water, their geographic range is quite large; extending across the Gulf, up the east coast to Labrador. They live in burrows on hard sandy bottoms and feed on crustaceans. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration2 reports this as a slow growing – long lived fish, up to 50 years of age. In their cold environment, this makes sense.

This is not a well-known fish along the Florida Panhandle but maybe one day you will see it on the menu, remember this article, and take a chance to see if you like it.

References

1 Hoese, H.D., Moore, R.H. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M Press. College Station TX. Pp. 327.

2 Golden Tilefish. 2020. Species Directory. NOAA Fisheries. https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/species/golden-tilefish.

by Rick O'Connor | Mar 18, 2022

When you look over the species of sea basses and groupers from the Gulf of Mexico it is a very confusing group. Hoese and Moore1 mention the connections to other families and how several species have gone through multiple taxonomic name changes over the years – its just a confusing group.

Gag grouper.

Photo: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

But when you say “grouper” everyone knows what you are talking about, and everyone wants a grouper sandwich. This became a problem because what people were serving as “grouper” may not have been “grouper”. And as we just mentioned what is a grouper anyway? The families and genera have changed frequently. Well, this will probably get more technical than we want, but to sort it out – at least using the method Hoese and Moore did in 1977 – we will have to get a bit technical.

“Groupers” are in the family Serranidae. This family includes 34 species of “sea bass” type fish. Serranids differ from snappers in that they lack teeth on the vomer (roof of their mouths) and they differ from “temperate basses” (Family Percichthyidae) in that their dorsal fin is continuous, not separated into two fins. These are two fish that groupers have been confused with.

Banked Sea Bass.

Photo: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

We can subdivide the serranids into two additional groups. The “sea basses” have fewer than 10 spines in their dorsal fin. There are 10 genera and 18 species of them. They have common names like “bass”, “flags”, “barbiers”, “hamlets”, “perch”, and “tattlers”. They are small and range in size from 2 – 18 inches in length. Most are bottom reef fish with little commercial value for fishermen. Most are restricted to the tropical parts of the Atlantic basin but two are only found in the northwestern Gulf, one is only found in the eastern Gulf, and one has been found in both the Atlantic and Pacific. The biogeography of this group is very interesting. The same species found in both the Atlantic and Pacific suggest an ancient origin. The variety of serranid sea bass suggest a lot of isolation between groups and a lot of speciation.

The ”groupers” have 10 or more spines in their dorsal fin. There are two genera in this group. Those in the genus Epinephelus have 8-10 spines in their anal fin and have some canine teeth. Those in the genus Mycteroperca have 10-12 spines in their anal fin and lack canine teeth. Within these two genera there are 15 species of grouper, though the common names of “hind”, “gag”, “scamp” are also used. Most of these are found along the eastern United States and Gulf of Mexico. Five species are only found in the tropical parts of the south Atlantic region, five are also found across the Atlantic along the coast of Africa and Europe, and – like the “sea bass” two have been found in both the Atlantic and the Pacific. They range in size from six inches to seven feet in length. The Goliath Grouper can obtain weights of 700 pounds! Like the sea bass, groupers prefer structure and can live a great depths. Unlike sea bass they are heavily sought by commercial and recreational anglers and are one of the more economically important groups of fish in the Gulf of Mexico.

The massive size of a goliath grouper. Photo: Bryan Fluech Florida Sea Grant

One interesting note on this family of fish is that most are hermaphroditic. The means they have both ovaries (to produce eggs) and testes (to produce sperm). Sequential hermaphrodism is when a species is born one sex but becomes the other later in life. This is the case with most groupers, who are born female and become male later in life. However, the belted sand bass (Serranus subligarius) is a true hermaphrodite being able to produce sperm and egg at the same time – even being able to self-fertilize.

For many along the Florida panhandle, their biogeographic distribution and sex do not matter. It is a great tasting fish and very popular with anglers. For those with a little more interest in natural history of fish in our area, the biology and diversity of this group is one of the more interesting ones.

Reference

1 Hoese, H.D., Moore, R.H. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M Press. College Station TX. Pp. 327.

by Rick O'Connor | Mar 11, 2022

The month of March is the last of winter. For todays hike we returned to Gulf Islands National Seashore/Ft. Pickens where it was 63°F, overcast with a strong breeze from the northwest. A cold front is coming through to remind us that winter is not over yet. It was not 44°F as it was on our February hike but with the wind and cloud cover, it was a bit cool and not ideal for most wildlife to be out. But the ospreys were…

Osprey perched.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

An osprey pair building a nest on the chimney of the ranger station at Ft. Pickens.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Another osprey pair with a nest in a large pine.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

They were everywhere. Building nests in live pines, dead snags, platforms built just for this, and on the chimney of the ranger station. Their sounds were everywhere – it is breeding season for them. The great blue herons were still nesting, we saw them first in January, but there are still a few around. American egrets were out as were numerous mourning doves. As with the colder February day, it was primarily bird action right now. I did see evidence of armadillos, and would guess other mammals were on the move, but did not see evidence of any others. The reptiles and amphibians are still missing – but should not be for long.

The herons began nesting in January. Some are still there.

Evidence of armadillos digging.

The plant I know as beach heather, many call false rosemary, and has the scientific name Conradina, was in full bloom. After the hollies of the Christmas season, these are the plants I often see bloom first. Though I have seen bees around my home already, and wasps, I did not see/hear any insect movement this morning.

Beach heather (false rosemary) is one of the first plants to bloom on our islands.

The north beach (Pensacola Bay) was rough due to the northwest wind. It was difficult to see if anything was moving around in the shallows. There were a lot of shells on the shore. Two particularly caught my eye. The Florida Fighting Conch was pretty abundant, more than normal – and there were several scallops shells. There are two species locally, the calico scallop (often found in the Gulf) and the bay scallop (the estuarine version and the one of “scalloping” fame). Calcio scallops are often pinkish in color and often with spots. The bay scallop is usually gray in color. Those I saw this morning were all bleached white but, based on other variety of shells in the mix, I am thinking these were calcio scallops.

There were several Florida Fighting Conch shells on the beach this month.

There was very little marine debris today and no tracks of any kind seen. There was only one lone pelican spotted, maybe due to the high winds they settled somewhere else. Maybe they have moved off to smaller islands for breeding themselves, I am not sure.

We only saw this one lone pelican today.

Though the wildlife has been more restricted to birds at the moment, the birding is excellent right now and the beach has relatively few people – it is a great time to take a hike out there.

This large tanker awaits its turn to enter Pensacola Bay.

This skull found along the side of the side of the road is believed to be a raccoon.

Lichen is an organism that is a partnership between algae and fungus. They were a brilliant white-green this month.

Razor clam shells are quite common along the shoreline.

Sand dollars are not as common on the bay side of the island but there were several today.

The remains of a ghost crab.

Believe it or not, walking along the road is a great spot to find wildlife.

by Rick O'Connor | Mar 11, 2022

Snook… Wait did you say Snook in the Florida panhandle?

Yep… they are not common, but they have seen here.

For those who do not know the fish and do not understand why seeing them is strange, this is a more tropical species associated with tarpon. In the early years of tourism in Florida tarpon fishing was one of the main reasons people came. Though bonefish and snook fishing were not has popular as tarpon, they were good alternatives and today snook fishing is popular in central and south Florida… but not in the north.

This snook was captured near Cedar Key. These tropical fish are becoming more common in the northern Gulf of Mexico.

Photo: UF IFAS

This fish is extremely sensitive to cold water, not liking anything under 60° F. They frequent the same habitats as tarpon, mangroves and marshes. They are euryhaline (having a wide tolerance for salinity) and can be found in freshwater rivers and springs. Actually, near river mouths is a place they frequent. The younger fish are more often found within the estuaries and adults have been found in the Gulf of Mexico. Again, this is a more tropical fish with records in Florida north of Tampa being rare. In the western Gulf the story is the same, almost all records are south of Galveston, Texas. Until recently…

Hoese and Moore1 cite a paper by Baughman (1943) that indicated the range of the fish had actually moved further south. One reason given was the loss of the much-needed salt marsh and mangrove habitats from human development. But in recent years there have more reports north of Tampa. Purtlebaugh (et al.)2 published a paper in 2020 indicating an increase in snook captured in the Cedar Key area of the Big Bend beginning in 2007. At first records only included adults, and the thought was these were “wayward” drifters in the region. But by 2018 they were capturing fish in all size classes and there was evidence of breeding going in the area. The range of the fish seemed to be moving north. The study suggests they still need warm water locations to over winter, and, like the manatees, springs seem to be working fine. But another piece of the explanation has been the reduction of hard freezes during winter in this part of the Gulf. Climate change may be playing a role here as well.

There seems to be other tropical species dispersing northward in a process some call “tropicalization” including the mangroves. There have been anecdotal reports of snook near Apalachicola where mangroves are becoming more common, and I know of two that were caught in Mobile Bay. There are mangroves growing on the Mississippi barrier islands as well. While explaining this during a presentation I was doing for a local group, a gentleman showed me a photo of a snook on his phone. I asked if he caught it in the Pensacola area. He replied yes. When I asked where, he just smiled… 😊 He was not going to share that. Cool.

There is no evidence that snook have established breeding populations are in our waters. Especially after this winter with multiple days with temperatures in the 30s, it is unlikely snook would be found here. But it is still interesting, and we encourage anyone who does catch one, to report it to us.

References

1 Hoese, H.D., Moore, R.H. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M Press. College Station Tx. Pp 327.

2 Purtlebaugh CH, Martin CW, Allen MS (2020) Poleward expansion of common snook Centropomus undecimalis in the northeastern Gulf of Mexico and future research needs. PLoS ONE 15(6): e0234083. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234083.