by Rick O'Connor | Jan 29, 2020

If you ask a kid who is standing on the beach looking at the open Gulf of Mexico “what kinds of creatures do you think live out there?” More often than not – they would say “FISH”.

And they would not be wrong.

According the Dr. Dickson Hoese and Dr. Richard Moore, in their book Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico, there are 497 species of fishes in the Gulf. However, they focused their book on the fish of the northwestern Gulf over the continental shelf. So, this would not include many of the tropical species of the coral reef regions to the south and none of the mysterious deep-sea species in the deepest part of the Gulf. Add to this, the book was published in 1977, so there have probably been more species discovered.

Schools of fish swim by the turtle reef off of Grayton Beach, Florida. Photo credit: University of Florida / Bernard Brzezinski

Fish are one of the more diverse groups of vertebrates on the planet. They can inhabit freshwater, brackish, and seawater habitats. Because all rivers lead to the sea, and all seas are connected, you would think fish species could travel anywhere around the planet. However, there are physical and biological barriers that isolate groups to certain parts of the ocean. In the Gulf, we have two such groups. The Carolina Group are species found in the northern Gulf and the Atlantic coast of the United States. The Western Atlantic Group are found in the southern Gulf, Caribbean, and south to Brazil. The primary factors dictating the distribution of these fish, and those within the groups, are salinity, temperature, and the bottom type.

Off the Texas coast there is less rain, thus a higher salinity; it has been reported as high 70 parts per thousand (mean seawater is 35 ppt). The shelf off Louisiana is bathed with freshwater from two major rivers and salinities can be as low as 10 ppt. The Florida shelf is more limestone than sand and mud. This, along with warm temperatures, allow corals and sponges to grow and the fish assemblages change accordingly.

Some species of fish are stenohaline – meaning they require a specific salinity for survival, such as seahorses and angelfish. Euryhaline fish are those who have a high tolerance for wide swings in salinity, such as mullet and croaker.

Courtesy of Florida Sea Grant. In total, it takes about 3 – 5 years for reefs to reach a level of maximum production for both fish and invertebrate species.

Forty-three of the 497 species are cartilaginous fish, lacking true bone. Twenty-five are sharks, the other 18 are rays. Sharks differ from rays in that their gill slits are on the side of their heads and the pectoral fins begins behind these slits. Rays on the other hand have their gill slits on the bottom (ventral) side of their body and the pectoral begins before them. Not all rays have stinging barbs. The skates lack them but do have “thorns” on their backs. The giant manta also lacks barbs.

Sharks are one of the more feared animals on the planet. 13 the 25 species belong to the requiem shark family, which includes bull, tiger, and lemon sharks. There are five types of hammerheads, dogfish, and the largest fish of all… the whale shark; reaching over 40 feet. The most feared of sharks is the great white. Though not believed to be a resident, there are reports of this fish in the Gulf. They tend to stay offshore in the cooler waters, but there are inshore reports.

The impressive jaws of the Great White.

Photo: UF IFAS

There is great variety in the 472 species of bony fishes found in the Gulf. Sturgeons are one of the more ancient groups. These fish migrate from freshwater, to the Gulf, and back and are endangered species in parts of its range. Gars are a close cousin and another ancient “dinosaur” fish. Eels are found here and resemble snakes. As a matter of fact, some have reported sea snakes in the Gulf only to learn later they caught an eel. Eels differ from snakes in having fins and gills. Herring and sardines are one of the more commercially sought-after fish species. Their bodies are processed to make fish meal, pet food, and used in some cosmetics. There are flying fish in the Gulf, though they do not actually fly… they glide – but can do so for over 100 yards. Grouper are one of the more diverse families in the Gulf and are a popular food fish across the region. There untold numbers of tropical reef fish. Surgeons, triggerfish, angelfish, tangs, and other colorful fish are amazing to see. Stargazers are bottom dwelling fish that can produce a mild electric shock if disturbed. Large billfish, such as marlins and sailfins, are very popular sport fish and common in the Gulf. Puffers are fish that can inflate when threatened and there are several different kinds. And one of the strangest of all are the ocean sunfish – the Mola. Molas are large-disk shaped fish with reduced fins. They are not great swimmers are often seen floating on their sides waiting for potential prey, such as jellyfish.

We could go on and on about the amazing fish of the Gulf. There are many who know them by fishing for them. Others are “fish watchers” exploring the great variety by snorkeling or diving. We encourage to take some time and visit a local aquarium where you can see, and learn more about, the Fish of the Gulf.

Reference

Hoese, H.D., R.H. Moore. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M University Press. College Station Texas. Pp. 327.

by Rick O'Connor | Jan 14, 2020

Standing on one of our local beaches, the Gulf of Mexico appears to be a wide expanse of emerald green and cobalt blue waters. We can see the ripples of offshore waves, birds soaring over, and occasionally dolphins breaking the surface. But few of us know, or think, about the environment beneath the waves where 99% of the Gulf lies. We might dream about catching some of the large fish, or taking a cruise, but not about the geology of the bottom, what the water is doing beneath the waves, or what other creatures might live there.

The Gulf of Mexico as seen from Pensacola Beach.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

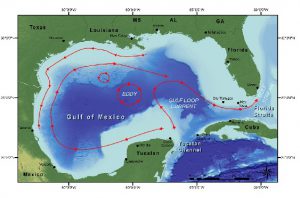

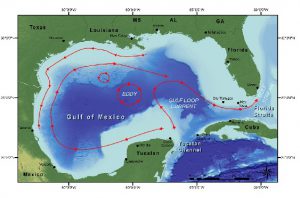

Scanning the horizon from the beach, you are gazing at 600,000 square miles of open water. It is about 950 miles from the panhandle to Mexico. Traveling at 10 knots, it would take you about 3 days to cross at its widest point. The Gulf is almost an enclosed body of water. The bottom is somewhat “bowl” shaped with the deepest portion slightly west of center at a location known as the Sigsbee Deep. The island of Cuba serves as the “median” between where the ocean enters and exits the Gulf. Cycling water from the Atlantic crosses from Africa, through the Caribbean, and enters the between Cuba and the Yucatan. The seafloor here sinks and spills into the Sigsbee Deep. The pass between Cuba and Yucatan is about 6500 feet deep and the bottom of the Sigsbee Deep is about 12,000. If you are looking due south from the Florida Panhandle, you would be looking at this pass.

If your gaze shifted slightly to the right – maybe “1:00” – you would be looking at the Yucatan. The Yucatan itself forms a peninsula and a portion of it is below sea level extending further into the Gulf. This submerged portion of the Yucatan is what oceanographers refer to as a continental shelf. On the “leeward” side of the Yucatan Peninsula lies an area of the Gulf known as the Bay of Campeche. There is a shallow section of this “bay” known as the Campeche Banks which supports amazing fisheries and some mineral extraction. Off the Yucatan shelf there is a current of water that rises from the ocean floor called an upwelling. These upwellings are usually cold water, high in oxygen, and high in nutrients – producing an area of high biological productivity and good fishing.

Continuing to circle the Sigsbee Deep and looking about “2:00”, northwest of the Bay of Campeche, you enter the western Gulf which extends from Vera Cruz Mexico to the Rio Grande River in Texas. The shelf is much closer to shore here and the marine environment is still tropical. There is a steep continental slope that drops into the Sigsbee Deep. Water from the incoming ocean currents usually do not reach these shores, rather they loop back north and east forming the Loop Current. The shelf extends a little seaward where the Rio Grande discharges, leaving a large amount of sediment. In recent years, due to human activities further north, water volume discharge here has decreased.

In the direction of about “2:30”, is the Northwestern Gulf. It begins about the Rio Grande and extends to the Mississippi Delta. Here the continental shelf once again extends far out to sea. One of the larger natural coral reefs in the Gulf system is located here; the Flower Gardens. This reef is about 130 miles off the coast of Texas. The cap is at 55 feet and drops to a depth of 160 feet. Because of the travel distance, and diving depth, few visit this place. Fishing does occur here but is regulated. This shelf is famous for billfishing, shrimping, and fossil fuel extraction. The Mississippi River, 15th largest in the world and the largest in the Gulf, discharges over 590,000 ft3 of water per second. The sediments of this river create the massive marshes and bayous of the Louisiana-Mississippi delta region, which has been referred to as the “birds’ foot” extending into the Gulf. This river also brings a lot of solid and liquid waste from a large portion of the United States and is home to one of the most interesting human cultures in the United States. There is much to discuss and learn about from this portion of the Gulf over this series of articles.

The basin of the Gulf of Mexico showing surface currents.

Image: NOAA

At this point we have almost completely encircled the Sigsbee Deep and move into the eastern Gulf. Things do change here. From the Mississippi delta to Apalachee Bay west of Apalachicola is what is known as the Northeastern Gulf – also known as the northern Gulf – locally called the Gulf coast. This is home to the Florida panhandle and some of the whitest beaches you find anywhere. Offshore the shelf makes a “dip” close to the beach near Pensacola forming a canyon known as the Desoto Canyon. The bottom is a mix of hardbottom and quartz sand. Near the canyon is good fishing and this area, along with the Bay of Campeche, is historically known for its snapper populations. It lies a little north of the Loop Current but is exposed to back eddies from it. Today there is an artificial reef program here and some natural gas platforms off Alabama.

Looking between “9:00-10:00” you are looking at the west coast of Florida and the Florida shelf. Here the shelf extends for almost 200 miles offshore. Off the Big Bend the water is shallow for miles supporting large meadows of seagrass and a completely different kind of biology. The rock is more limestone and the water clearer. In southwest Florida the grassflats support a popular fisheries area and a coral system known as the Florida Middle Grounds. At the edge of the shelf is a steep drop off called the Florida Escarpment, which forms the eastern side of the “bowl”. Another ocean upwelling occurs here.

Looking at “11:00” you are looking towards the Florida Keys. Between the Keys and Cuba is the exit point of the Loop Current called the Florida Straits. It is not as deep as here as it is between Cuba and the Yucatan; only reaching a depth of 2600 feet. This is mostly coral limestone and the base of one of the largest coral reef tracks in the western Atlantic. The coral and sponge reefs, along with the coastal mangroves, forms one of the more biological productive and diverse regions in our area. It supports commercial fishing and tourism.

We did not really talk about the bottom of the “bowl”. Here you find remnants of tectonic activity. Volcanos are not found but you do find cold and hot water vent communities, which look like chimneys pumping tremendous amounts of thermal water from deep in the Earths crust. These vent communities support a neat group of animals that we are just now learning about. Brine lakes have also been discovered. These are depressions in the seafloor where VERY salty water settles. These “lakes” have water much denser than the surrounding seawater and can even create their own waves. Many of them lie as deep as 3300 feet and can be 10 feet deep themselves. There is one known as the “Jacuzzi of Despair”. They are so salty they cannot support much life.

In the next addition to this series we will begin to look at the some of the interesting plant and animals that call the Gulf home.

Embrace the Gulf.

by Rick O'Connor | Jan 10, 2020

It’s an amazing place really – the Gulf of Mexico. Covering over 598,000 square miles this almost a complete circle of water and home to some interesting geological features, amazing marine organisms, some of busiest ports in the United States, offshore mineral extraction, great vacation locations, and amazing local culture.

View from the Navarre Beach pier Photo credit: Lydia Weaver

As you stand along Pensacola Beach and look south, you see a wide expanse of water that seems to go on forever. However, in oceanographic terms, the Gulf is not that large of a body of water. Though it is close to 600,000 square miles in size, the Atlantic Ocean is 41,000,000 and the Pacific is 64,000,000 square miles. In addition to area, the mean depth of the Atlantic is a little over 12,000 feet and the Pacific is 14,000 feet. In comparison, the deepest point of the Gulf is 14,000 feet and the mean depth is only 5,000. The shape of the bottom is like a ceramic bowl that was not centered well when fired. The deepest point, the Sigsbee Deep, is about 550 miles southwest (about “2:00” if you are looking from the beach). The shape appears like a hole made by a golf ball that landed in a sand trap. As a matter of fact, there are scientists who believe this is exactly what happened – a large asteroid or comet made have hit the Earth near the Gulf forming a large series of tsunamis and created the Gulf as we know it today.

Either way the “pond” (as some oceanographers refer to it) is an amazing place. The bottom is littered with hot vents, brine lakes, and deep-sea canyons. Large areas of the continental shelf support coral reef formation and a great variety of marine life. Some of the busiest ports in the United States are located along its shores, and it supplies 14% of the wild domestic harvested seafood. Everyone is aware of the mineral resources supplied on the western shelf of the Gulf and the tremendous tourism all states and nations that bordering enjoy.

The emerald waters of the Gulf of Mexico along the panhandle.

This year the Gulf of Mexico Alliance will be celebrating “Embracing the Gulf” with a variety of activities and programs across the northern Gulf region. We will be dedicating this column to articles about the Gulf of Mexico all year and discussing some of the topics mentioned above in more detail. We hope you enjoy your time here and get a chance to explore the Gulf’s seafood, fishing, diving, marine life, ship cruises, unique cultures, and awesome sunsets. Embrace the Gulf!

by Rick O'Connor | Sep 9, 2019

Many people enjoy scallops. Just as many enjoy scalloping.

It is a great Florida family activity where everyone gets to snorkel in relatively shallow – safe waters. You explore the grassbeds for a myriad of cool marine creatures yelling across the bay to friends about all the neat things you are seeing.

Bay Scallop Argopecten iradians

http://myfwc.com/fishing/saltwater/recreational/bay-scallops/

And of course, there are the scallops. Sitting on top of the grass blades with their undulated ridged shells and ice blue eyes. You reach to grab one and they begin the “clap” their shells together to escape being captured. You finish the adventurous day with your limit of scallops, and it is time to eat – broiled in butter and some seasoning is my favorite.

It is great fun. However, it is becoming harder to find them.

Once found in grassbeds from Pensacola to Miami, the recreational harvest has been restricted to the Big Bend area – the commercial no longer happens. Everywhere their numbers are down and many locations within their historic range, you cannot even find them. Since 2015, Florida Sea Grant has conducted scallop searches in the Pensacola Bay area using citizen volunteers and have found only one live animal. We have found numerous shells of these creatures, who only live a year… maybe two. We have had reports of live scallops in the bay area outside of our formal search dates, I have personally found some, but the numbers are still very low – low enough that recreational harvesting in the Pensacola Bay area is closed indefinitely.

The story is the same from south of the Big Bend. Scallop searches are conducted every year and returns are low, or non-existent. So, the focus turns the Big Bend.

They are famous for the scallop seasons. Floridians travel from all neighboring counties, and from across the state, to partake in this fun activity. It is good business for these local communities. For some, it is the biggest money maker of the year. However, now we are hearing stories of low harvest numbers in some parts of the Big Bend. In recent years, Port St. Joe Bay has suffered from algal blooms and red tide that not only closed the waters to harvesting for swimming safety reasons, but because the scallop numbers declined as well. One story out of Hernando County indicated that the numbers in this region are now down. You must consider overharvesting as a problem as well.

Prepared properly: One of the finest meals you will ever have.

FWC is interested in restoring these animals to parts of their range where they were once common. The Scallop Sitters program is one where volunteers can hang caged scallops raised in state hatcheries from their docks, protected from predators, and allow them to mass spawn. The first pilot project in our area was in Bay and Gulf counties… last year… when Hurricane Michael came through. Obviously, they will have to start over.

What is needed to extend this project into other bay areas?

Well, you certainly do not want to put them into waters where you know they will die. The scallop populations declined for a reason – primarily habitat loss and overharvesting. Excessive stormwater runoff decreased much needed salinity and increased grass killing turbidity. Loss of seagrass equates to loss of scallops. Florida Sea Grant is currently working with the University of West Florida, and citizen volunteers, to monitor seagrass growth and density in Santa Rosa Sound and Big Lagoon. We will have a report on this year’s work later this fall. We are also working with citizen scientists monitoring salinity in these bodies of water hoping for a mean of 20 parts per thousand or better. We will have the summer salinity reports out at the end of September. We hope these data will support the argument of extending the scallop sitters program further west.

A pile of cleaned scallops found in a parking lot on Pensacola Bay. harvesting scallop in Pensacola Bay is illegal.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

But there is the question of overharvesting.

In recent years we have found evidence of locals in the Pensacola Bay area illegally harvesting the few scallops we have. Some residents do not know that it is illegal to harvest in these waters – it is – and the only way we can successfully restore them, is allow them to mass spawn. To do this, we need large numbers.

Each year Florida Sea Grant conducts the Great Scallop Search in the Pensacola Bay area. We also host a “Bio-Scavenger Hunt” in the fall where scallops are one of the target species. If you are interested in volunteering, contact Rick O’Connor at the Escambia County Extension Office – (850) 475-5230 ext. 111, or roc1@ufl.edu.

by Rick O'Connor | Sep 6, 2019

It is an amazing product actually… plastic. It can be molded into all sorts of shapes and forms. In some cases, it can be more durable than other products, it is lighter and cheaper than many. Slowly over time, we began to use more and more of it. I remember as a kid in the ‘60s Tupperware products were common. Cups and bowls with resealable lids. Coffee cups followed, then 2-Liter coke bottles, to the common water bottle we see today. As I look around the room, I am in right now there are plastic pens, picture frames, suntan lotion bottles, power cords, rain jacket, the cover and keyboard of this laptop. Plastic is part of our lives.

A variety of plastics ends up in the Gulf. Each is a potential problem for marine life. Photo: Rick O’Connor

Unfortunately, being relatively inexpensive, it is also easily disposed of. Many forms of plastic are one-time use. In some cases, we purchase and discard them without really using them – plastic wrap covering fruit, or the famous plastic grocery bags. Most of this discarded plastic eventually finds its way into the environment. Data from the 2017 International Coastal Clean Up, showed that globally all the top 10 items collected were plastic. Most of it was cigarette butts and items related to food and drink. Even with all the press, the number of plastic grocery bags collected actually increased. One study conducted in 2015 estimated the amount of plastic in our oceans would be enough to fill 5 plastic grocery bags for each foot of shoreline of the 192 countries they surveyed.

There is a lot of plastic out there. One researcher commented… it’s all still there. Some have estimated that plastic takes about 600 years to completely break down. Plastic items degrade while exposed to sun, sand, and saltwater. But they never go away. They become smaller and smaller to a point where you cannot even see them anymore – these are called MICROPLASTICS.

Microplastics are defined as any plastic items 5mm or smaller in diameter. Most plastics float, and most microplastics float as well, but pieces of microplastics have been found throughout the water column and even in the deep-sea sediments. They come in two forms; primary and secondary.

“Nurdle” are primary microplastics that are produced to stuff toys and can be melt down to produce other products.

Photo: Maia McGuire

Primary microplastics are plastics that are produced at these small sizes. All plastic products begin as small beads called nurdles. Nurdles are produced and shipped to manufacturing centers where they are melted down and placed into forms which produce car bumpers, notebook covers, and water bottles. Many of these nurdles are shipped via containers and spills occur. Other primary microplastics are microbeads. These are used in shampoo, toothpaste, and other products to make them sparkle, or add color. As they are washed down our sinks and showers, they eventually make their way into the environment. Sewage treatment facilities are designed to remove them.

Secondary microplastics are those they were originally macroplastics and have been broken down by the elements. Plastic fragments and fibers are two of the more common forms of secondary microplastics. These micro-fibers make up 70-80% of the microplastics volunteers find in Florida waters. Many of these fibers come from our clothing, from cigarette butts, and other sources.

Are these microplastics causing a problem?

It is hard to say whether they have caused the decline in populations of any group of marine organisms, but we do know they are absorbing them. Studies have found microscopic plankton have ingested them, and some have ceased to feed until they pass them, if they do pass them. There has been concerned with the leaching of certain products in plastic to make them more flexible in bottled water. These products have been found in both plankton and in whales.

The most common form of microplastic are fibers.

Photo: UF IFAS St. Johns County

Another problem are the toxic compounds already in seawater. Compounds such as PCBs, PAHs, and DDT. It has been found that these compounds adhere to microplastics. Thus, if marine organisms consume (or accidentally ingest) these microplastics, the concentrations of these toxins are higher than they would be if the microplastics were not present.

Studies have shown:

– Pacific oysters had decreased egg production and sperm motility, fewer larvae survived, and the survivors grew more slowly than those in the control population.

– Plastic leachate impaired development of brown mussel larvae.

– Shore crabs fed microplastics consumed less food over time.

A recent summer research project at the University of West Florida found microplastics within the gut and tissues of all seafood products purchased in local seafood markets. And recently a study of human stool samples from volunteers in Europe and Japan found microplastics in us. Again, we are not sure of the impact on our health from this, but they are there.

So, what do we do?

One idea is to remove these microplastics from the ocean – skimming or filtering somehow. As you might guess, this also removes much needed phytoplankton and zooplankton.

There is the ole “Recycle, Reuse, Reduce” idea we learned when we were in school. Unfortunately, recycling plastic has not been working well. Being a petroleum product, the price of oil can dictate the price of recycled plastic. With low oil prices comes low recycling profits. In many cases it can be cheaper to produce and purchase new plastic products. Also, unlike glass, plastic can only be recycled so many times.

Boxes providing garbage bags and disposal.

Photo: Pensacola Beach Advocates

Reuse and reduce may be the better options. If you must purchase plastic items, try to reuse them. In many cases this is difficult and the reduce method is the better option. Reduce the purchase of plastic items such as your own drinking container instead of using the one-time plastic cup at meetings or events. And of course, reusable grocery bags. You will have to think on how to reduce some items, but most can be done.

There are numerous more suggestions, and more information, on Dr. Maia McGuire’s Flagler County Extension website – http://sfyl.ifas.ufl.edu/flagler/marine-and-coastal/microplastics/.

Help make others more aware of microplastics during Microplastics Awareness Month.

by Erik Lovestrand | Aug 16, 2019

If you like summer fireworks events, there is a great show ongoing during our warm summer months that you shouldn’t miss. Find an unlit dock along our coastal environs and take the time to pause, get down on your knees, and gaze into the starry… water. Our night skies are quite impressive in their own right, but our night waters will also put on an amazing show of glowing critters and flashing lights if you take the time to notice. Thousands of different marine organisms have the ability to produce light and the purposes served by this trait are many. Some animals use this tactic as camouflage and others to stand out for one reason or another. Being seen by others can assist with predation (luring), defense (startling or warning), or even reproduction (attracting a mate).

Thousands of marine creatures create their own light, including many jelllyfish

Bioluminescence is the most accurate term for light emitted by living organisms; although sometimes you will hear it referred to as fluorescence or phosphorescence. Fluorescence however, is the term describing something that absorbs light energy from an external source and then almost immediately re-emits it. When the external source goes away, so does the fluorescence; i.e. it doesn’t keep going in the dark. Phosphorescence describes when something absorbs light energy from an external source and then slowly re-emits it over a longer timeframe, i.e. glowing stickers. In contrast to these other terms, bioluminescence results from a chemical reaction within the body of an organism. The trigger mechanisms can be quite varied in nature and some are even directly controlled by linkages with an animal’s brain and nervous system. Other times the light is triggered simply by a physical disturbance. This is the most common phenomenon observed by people as the water seems to sparkle from a boat’s wake at night or waves breaking in the surf. One of my earliest memories of this was as a teenager in the Keys while wading along the shore at night. Each splash would trigger a shower of sparks.

So, what is taking place to create this chemical reaction that gives off light? Well, scientists have learned a lot about it but still don’t have all of the answers regarding the incredible variety of ingredients and processes involved in the bioluminescent realm. In general, a molecule called luciferin is involved and when exposed to oxygen, it gives off light. An enzyme named luciferase acts as a catalyst to help speed up the reaction. There are apparently many types of luciferins utilized by different animals; and I’m guessing, many variations on the actual luciferases involved too.

During summertime the warm waters of the Gulf and our coastal estuaries are rich with planktonic life. If you look close at a dock post beneath the water you will see continual, tiny flashes being triggered as water moves around the stationary post. When you walk down the dock (very carefully, without a flashlight), you can also see streaks of light from startled fish swimming away. This light is emitted by single-celled dinoflagellates that are triggered by a disturbance near them. One fascinating account I’ve read, told the story of Jim Lovell (Apollo 13 astronaut), who used bioluminescence to find his way safely home. When the navigation equipment failed at night in the navy plane he was flying, he was able to turn off his cockpit lights and see the glowing wake from his carrier and follow it. I’m sure he was forever grateful to the tiny marine creatures that made this possible! If you can get to a coastal dock near you this summer, be sure to turn out the lights, and look down in the water for a spectacular, miniature fireworks show. No earplugs required.