by Rick O'Connor | Apr 5, 2020

We began this series on the Gulf talking about the Gulf itself. We then moved to the big, more familiar – maybe more interesting animals, the vertebrates – birds, fish, etc. In this edition we shift to the invertebrates – the “spineless” animals of the Gulf of Mexico. Many of them we know from shell collecting along the beach, others are popular seafood choices, but most we know nothing about and rarely see.

A spineless Comb Jelly.

Florida Sea Grant

They are numerous, on diversity alone – making up 90% of the animal kingdom. They may leave remnants behind so that we know they are there. They may be right in front of our faces, but we do not know what we are looking at. They are incredibly important. Providing numerous nutrient transport, and transfer, in the ecosystem – that would otherwise not exist. They also provide a lot of ecological services that reduce toxins and waste. One source suggests there are over 30 different phyla and over one million species of invertebrates. In this series we will cover six major groups and we begin with the simplest of them all… the sponges.

For some, you may not know that sponges are actually alive. For others, you knew this but were not sure what kind of creature it was. Are they plants? Animals? Just a sponge?

The answer is animal. Yea…

We usually think of animals as having legs, running around, eating things and defecting in places – the kinds of things that make good animal planet shows.

Sponges… would not make a great animal planet show. What are you going to watch? They appear to be doing nothing. They sit on the ocean floor… and… well… that’s it, they sit on the ocean floor. But they actually do a lot.

A vase sponge.

Florida Sea Grant

They are considered animal because (a) their cells lack a cell wall – which plants have, and (b) they are heterotrophic… consumers… they have to hunt their food and cannot make it as plants do.

What do they eat?

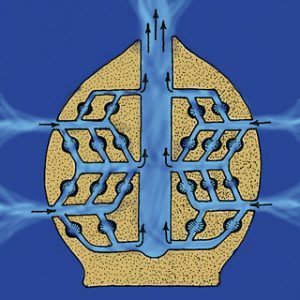

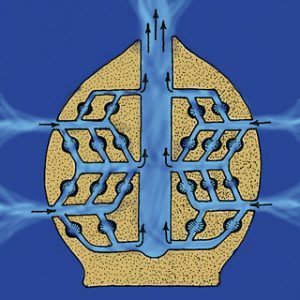

Plankton. Lots of plankton. Looking at a sponge you would call it one animal, but it is actually a colony of specialized cells working as a unit to survive. There are cells with flagella, called collar cells, that use these flagella to create currents that “suck” water into the body of the creature. This is how they collect plankton. The collar cells live in numerous channels throughout the sponge body connected to small pores all over the service of the sponge. This is where they get their phylum Porifera. As the water moves through the channels, the collar cells remove food and specialized cells called choanocytes release reproductive eggs called gemmules. All of the water eventually collects in a cavity, called the gastrovascular cavity where it exists the sponge through a large opening called an osculum.

This is how they eat and reproduce.

The anatomy of a sponge.

Flickr

The matrix, or tissue, of the sponge is held together by small, hard structures called spicules. It sort of serves as a skeleton for the creature. In different sponges the spicules are made of different materials, and this is how the creatures are divided into classes. Some are made of calcium carbonate, like seashells. Others are made of silica and are “glass-like”, and some made of a softer material called “spongin”, which are the ones we use to take baths with. Today purchased sponges are synthetic, not natural – but you can still get natural sponges.

Many sponges are tiny, others are huge. They all like seawater – not big fans of freshwater – and many produce mild toxins to defend the from predators. They do have predators though – hawksbill sea turtles love them. There is currently a lot of research going on using sponge toxins to kill cancer cells. Who knows, the cure to some forms of cancer may lie in the cavity of the sponge.

Another cool thing about them is that their cavities provide a lot of space for other small creatures in the ocean. Numerous species can be found in sponge tissue and cavities, utilizing this space as a habitat for themselves.

Florida Sea Grant

They are a major player in the development of reefs in the tropics and, like their counter parts coral, have experienced a decline due to over harvesting and harmful algal blooms. There are efforts in the Florida Keys to grow new sponge in aquaculture facilities and “re-plant” in the ocean. In the northern Gulf they are more associated with seagrass beds.

These are truly amazing creatures and the more we learn about them, the more amazing they become.

References:

Myriad World of the Invertebrates. EarthLife. https://www.earthlife.net/inverts/an-phyla.html.

by Rick O'Connor | Mar 24, 2020

Article By: Whitney Cherry

4-H Agent Calhoun County

I know COVID-19 has been driving public and private discussion as of late. But, we have to stay vigilant in working against all public health threats. One of those threats we typically start talking about this time of year is mosquito borne illnesses and preventative mosquito control. Not only are mosquitoes pests, but they can transmit some pretty nasty diseases we wouldn’t want under normal circumstances. But with our healthcare system currently inundated with COVID-19 patients, we certainly wouldn’t want to unnecessarily add to the burden.

Adult female yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti (Linnaeus), in the process of seeking out a penetrable site on the skin surface of its host.

Credit: James Gathany, Center for Disease Control Public Health Image Library Source: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/in792

So what’s the reality? While the incidence of mosquito borne illness is much lower with the advent of modern medicine and basic public practices of wearing bug spray and dumping or treating standing water, it’s definitely not unheard of. The Zika scare is not such a distant memory after all. And EEE (eastern equine encephalitis) was at an unusual high last year in horses in the panhandle. So what can we do?

With recent flooding in some areas and the weather warming, we can expect to see increasing populations of mosquitoes. Additionally, as the weather warms, we all tend to spend more time outside, increasing our likelihood of mosquito bites. Further exacerbating the situation is the widespread quarantine measures keeping many of us home. The late afternoon and early evening hours bring ideal weather to step outside and enjoy a little time away from TV and computer screens. We encourage fresh air and exercise outdoors, but we also encourage basic safety. So wear bug spray if you’re outside early morning and especially near, during, or shortly after dusk. Wear long sleeves and pants and socks if you can stand it. And keep standing water dumped out of containers on your property. If this isn’t possible, look for safe water treatment options. The most prevalent spreaders of disease (Aedes aegypti) actually require these containers of water to complete their lifecycle.

For more information on this or other Extension-related topics, call or email your local extension office.

Related information: http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/results.html?q=mosquito+borne+illness&x=0&y=0#gsc.tab=0&gsc.q=mosquito%20borne%20illness&gsc.page=1

by Rick O'Connor | Feb 13, 2020

An eastern cottonmouth basking near a creek in a swampy area of Florida.

Photo: Tommy Carter

When you think of reptiles you typically think of tropical rainforest or the desert. However, there is at least one member of the three orders of reptiles that do live in the sea. Saltwater crocodiles are found in the Indo-Pacific region as are about 50 species of sea snakes. There is one marine lizard, the marine iguana of the Galapagos Islands, and then the marine (or sea) turtles. These are found worldwide and are the only true marine reptiles found in the Gulf of Mexico.

Sea turtles are very charismatic animals and beloved by many. Five of the seven species are found in the Gulf. These include the Loggerhead, which is the most common, the Green, the Hawksbill, the Leatherback, and the rarest of all – the Kemp’s Ridley.

Many in our area are very familiar with the nesting behavior of these long-ranged animals. They do have strong site fidelity and navigate across the Gulf, or from more afar, to their nesting beaches – many here in the Pensacola Beach area. The males and females court and mate just offshore in early spring. The females then approach the beach after dark to lay about 100 eggs in a deep hole. She then returns the to the Gulf never to see her offspring. Many females will lay more than one clutch in a season.

The largest of the sea turtles, the leatherback.

Photo: Dr. Andrew Colman

The eggs incubate for 60-70 days and their temperature determines whether they will be male or female, warmer eggs become females. The hatchlings hatch beneath the sand and begin to dig out. If they detect problems, such as warm sand (we believe meaning daylight hours) or vibrations (we believe meaning predators) they will remain suspended until those potential threats are no more. The “run” (all hatchlings at once) usually occurs under the cover of darkness to avoid predators. The hatchlings scramble towards the Gulf finding their way by light reflecting off the water. Ghost crabs, fox, raccoon, and other predators take almost 90% of them, and the 10% who do reach the Gulf still have predatory birds and fish to deal with. Those who make it past this gauntlet head for the Sargassum weed offshore to begin their lives.

These are large animals, some reaching 1000 pounds, but most are in the 300-400 pound range, and long lived, some reaching 100 years. It takes many years to become sexually mature and typically long-lived / low reproductive animals are targets for population issues when disasters or threats arise. Many creatures eat the small hatchings, but there are few predators on the large reproducing adults. However, in recent years humans have played a role in the decline of the adult population and all five species are now listed as either threatened or endangered and are protected in the U.S. There are a couple of local ordinances developed to adhere to federal law requiring protection. One is the turtle friendly lighting ordinance, which is enforced during nesting season (May 1 – Oct 31), and the Leave No Trace ordinance requiring all chairs, tents, etc. to be removed from the beach during the evening hours. There are other things that locals can do to help protect these animals such as: fill in holes dug on the beach during the day, discard trash and plastic in proper receptacles, avoid snagging with fishing line and (if so) properly remove, and watch when boating offshore to avoid collisions.

If we include the barrier islands there are more coastal reptiles beyond the sea turtles. There are freshwater ponds which can harbor a variety of freshwater turtles. I have personally seen cooters, sliders, and even a snapping turtle on Pensacola Beach. Many coastal islands harbor the terrestrial gopher tortoise and wooded areas could harbor the box turtles. In the salt marsh you may find the only brackish water turtle in the U.S., the diamondback terrapin. These turtles do nest on our beaches and are unique to see. Freshwater turtle reproductive cycles are very similar to sea turtles, albeit most nest during daylight hours.

An American Alligator basking on shore.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

The American alligator can also be found in freshwater ponds, and even swimming in saltwater. They can reach lengths of 12 feet, though there are records of 15 footers. These animals actually do not like encounters with humans and will do their best to avoid us. Problems begin when they are fed and loose that fear. I have witnessed locals in Louisiana feeding alligators, but it is a felony in Florida. Males will “bello” in the spring to attract females and ward off competing males. Females will lay eggs in a nest made of vegetation near the shoreline and guard these, and the hatchlings, during and after birth. They can be dangerous at this time and people should avoid getting near.

We have several native species of lizards that call the islands home. The six-lined race runners and the green anole to name two. However, non-native and invasive lizards are on the increase. It is believed there are actually more non-native and invasive lizards in Florida than native ones. The Argentina Tegu and the Cuban Anole are both problems and the Brown Anole is now established in Gulf Breeze, East Hill, and Perdido Key – probably other locations as well. Growing up I routinely find the horned lizard in our area. I was not aware then they were non-native, but by the 1970s you could only find them on our barrier islands, and today sightings are rare.

An eastern cottonmouth crossing a beach.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

Then there are the snakes.

Like all reptiles, snakes like dry xeric environments like barrier islands. We have 46 species in the state of Florida, and many can be found near the coast. Though we have no sea snakes in the Gulf, all of our coastal snakes are excellent swimmers and have been seen swimming to the barrier islands. Of most concern to residents are the venomous ones. There are six venomous snakes in our area and four of them can be found on barrier islands. These include the Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake, the Pygmy Rattlesnake, the Eastern Coral Snake, and the Eastern Cottonmouth. There has been a recent surge in cottonmouth encounters on islands and this could be due to more people with more development causing more encounters, or there may be an increase in their populations. Cottonmouths are more common in wet areas and usually want to be near freshwater. Current surveys are trying to determine how frequently encounters do occur.

Not everyone agrees, but I think reptiles are fascinating animals and a unique part of the Gulf biosphere. We hope others will appreciate them more and learn to live with and enjoy them.

by Rick O'Connor | Feb 5, 2020

This is one of the most beloved animals on the planet… sea turtles. Discussions and debates over all sorts of local issues occur but when sea turtles enter the discussion, most agree – “we like sea turtles”, “we have nothing against sea turtles”. There are nonprofit groups, professional hospitals, and special rescue centers, devoted to helping them. I think everyone would agree, seeing one swimming near the shore, or nesting, is one of the most exciting things they will ever see. For folks visiting our beaches, seeing the white sand and emerald green waters is amazing, but it takes their visit to a whole other level if they encounter a sea turtle.

The largest of the sea turtles, the leatherback.

Photo: Dr. Andrew Colman

They are one of the older members of the living reptiles dating back 150 million years. Not only are they one of the largest members of the reptile group, they are some of the largest marine animals we encounter in the Gulf of Mexico.

There are five species of marine turtles in the Gulf represented by two families. The largest of them all is the giant leatherbacks (Dermochelys coriacea). This beast can reach 1000 pounds and have a carapace length of six feet. Their shell resembles a leatherjacket and does not have scales. Because of their large size, they can tolerate colder temperatures than other marine turtles and found all over the globe. They feed almost exclusively on jellyfish and often entangled in open ocean longlines. There is a problem distinguishing clear plastic bags from jellyfish and many are found dead on beaches after ingesting them. Like all sea turtles, they approach land during the summer evenings to lay their eggs above the high tide line. The eggs incubate within the nest for 65-75 days and sex determination is based on the temperature of the incubating eggs; warmer eggs producing females. Also, like other marine turtles, the hatchlings can be disoriented by artificial lighting or become trapped in human debris, or unnatural holes, on the beach. These animals are known to nest in Florida and they are currently listed as federally endangered and are completely protected.

The large head of a loggerhead sea turtle.

Photo: UF IFAS

The other four species are found in the Family Chelonidae and have the characteristic scaled carapace. Much smaller than the leatherback, these are still big animals. The most common are the loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta). As the name suggest, the head of this sea turtle is quite large. Their carapace can reach lengths of four feet and they can weigh up to 450 pounds. The head usually has four scutes between the eyes and three scutes along the bridge connecting the carapace to the plastron. This animal prefers to feed on a variety of invertebrates from clams, to crabs, to even horseshoe crabs. It too is an evening nester and the young have similar problems as the leatherback hatchlings. The tracks of the nesting turtle can be identified by the alternating pattern made by the flippers. One flipper first, then the next. The loggerhead is currently listed as a federally threatened species.

A green sea turtle on a Florida beach.

Photo: Florida Sea Grant

The green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) is called so not for the color of its shell, but for the color of its internal body fat. They are fans of eating seagrasses, particularly “turtle grass” and other plants, which produce the green coloration of the fat. The fat is used to produce a world favorite, “turtle soup”, and has been a problem for the conservation of this species in some parts of the world. At one time, most green turtles nested in south Florida, but each year the number nesting in the north has increased. They can be distinguished from the loggerhead in that (1) their head is not as big, (2) there are only two scales between the eyes, and (3) their flipper pattern in sand is not alternating; green turtles throw both flippers forward at the same time. Green turtles are listed as federally threatened.

A hawksbill sea turtle resting on a coral reef in the Florida Keys.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

The hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) is more tropical in distribution. They are a bit smaller, with a carapace length of three feet and a weight of 187 pounds, but their diet of sponges is another reason you do not find them often in the northern Gulf of Mexico. To feed on these, they have a “hawks-bill” designed to rip the sponges from their anchorages. Their shell is gorgeous and prized in the jewelry trade. “Tortoise-shell” glasses and earrings are very popular.

The most endangered of them all is the small Kemp’s Ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys kempii). This little guy has a carapace length of a little over two feet and weighs in at no more than 100 pounds. These guys are commonly seen in the Big Bend area of Florida but for years no one knew where they nested. That was until 1947 when an engineer from Mexico found them nesting in large numbers (up to 40,000) at one time, in broad daylight in Rancho Nuevo, Mexico. This was problematic for the turtle because the locals would wait for the nesting to be complete before they would take the females and the eggs. Protected today they now face the problem that their migratory path across the Gulf takes them through Texas and Louisiana shrimping grounds, and through the 2010 Deep Water Horizon oil spill field. Not to mention that illegal poaching still occurs. Though all species of sea turtles have had problem with shrimp trawls, the Kemps had a particular problem, which led to the develop of the now required Turtle Excluder Device (T.E.D.S) found on shrimp trawls in the U.S. today. Sea turtles have strong site fidelity for nesting and in the 1980s many Kemp’s Ridley eggs were re-located to beaches in Texas in hopes to move the nesting to other locations. The program had some success and they have been reported to nest in Florida. Their diet consists primarily of crabs but there have been reports of them removing bait from fishing lines fishing from piers over the Gulf. This is species is federally endangered and is considered by many to be the most endangered sea turtle species on the planet.

Turtle friendly lighting.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Sea turtles face numerous human-caused problems including (1) artificial lighting that disorient hatchlings and cause mortality to 50% (or more) of the hatchlings, (2) items left on beaches (such as chairs, tents, etc.) that can impede adults and entrap hatchlings, (3) large holes dug on beaches in which hatchlings fall and cannot get out, (4) marine debris (such as plastics) which they confuse with prey and swallow, (5) boat strikes, sea turtles must surface to breath and can become easy targets, and (6) discarded fishing gear, in which they can become entangled and drown. These are simple things we can correct and protect these amazing Florida turtles.

References

Buhlmann, K., T. Tuberville, W. Gibbons. 2008. Turtles of the Southeast. University of Georgia Press, Athens GA. Pp. 252.

Florida’s Endangered and Threatened Species. 2018. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. https://myfwc.com/media/1945/threatend-endangered-species.pdf,

Species of Sea Turtle Found in Florida. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. https://myfwc.com/research/wildlife/sea-turtles/florida/species/.

by Andrea Albertin | Jan 31, 2020

Contact you local county health department office for information on how to test your well water. Image: F. Alvarado Arce

Residents that rely on private wells for home consumption are responsible for ensuring the safety of their own drinking water. The Florida Department of Health (FDOH) recommends private well users test their water once a year for bacteria and nitrate.

Unlike private wells, public water supply systems in Florida are tested regularly to ensure that they are meeting safe drinking water standards.

Where can you have your well water tested?

Your best source of information on how to have your water tested is your local county health department. Most health departments test drinking water and they will let you know exactly what samples need to taken and ho w to submit a sample. You can also submit samples to a certified private lab near you.

Contact information for county health departments can be located at: http://www.floridahealth.gov/programs-and-services/county-health-departments/find-a-county-health-department/index.html

Contact information for private certified laboratories are found at https://fldeploc.dep.state.fl.us/aams/loc_search.asp

Why is it important to test for bacteria?

Labs commonly test for both total coliform bacteria and fecal coliforms (or E. coli specifically). This usually costs about $25 to $30, but can vary depending on where you have your sample analyzed.

- Coliform bacteria are a large, diverse group of bacteria and most species are harmless. But, a positive test for total coliforms shows that bacteria are getting into your well water. They are used as indicators – if coliform bacteria are present, other pathogens that cause diseases may also be getting into your well water. It is easier and cheaper to test for total coliforms than to test for a suite of bacteria and other organisms that can cause health problems.

- Fecal coliform bacteria are a subgroup of coliform bacteria found in human and other warm-blooded animal feces, in food and in the environment. E. coli are one group of fecal coliform bacteria. Most strains of E. coli are harmless, but some strains can cause diarrhea, urinary tract infections, and respiratory illnesses among others.

To ensure safe drinking water, FDOH strongly recommends disinfecting your well if the water tests positive for (1) only total coliform bacteria, or (2) both total coliform and fecal coliform bacteria (or E. coli). Disinfection is usually done through shock chlorination. You can either hire a well operator in your area to disinfect your well or you can do it yourself. Information for how to shock chlorinate your well can be found at http://www.floridahealth.gov/environmental-health/private-well-testing/_documents/well-water-facts-disinfection.pdf

Why is it important to test for nitrate concentration?

High levels of nitrate in drinking water can be dangerous to infants, and can cause “blue baby syndrome” or methemoglobinemia. This is where nitrate interferes with the blood’s capacity to carry oxygen. The Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) allowed for nitrate in drinking water is 10 milligrams nitrate per liter of water (mg/L). It is particularly important to test for nitrate if you have a young infant in the home that is drinking well water or when well water is used to make formula to feed the infant.

If test results come back above 10 mg/L nitrate, use water from a tested source (bottled water or water from a public supply) until the problem is addressed. Nitrates in well water can come from fertilizers applied on land surfaces, animal waste and/or human sewage, such as from a septic tank. Have your well inspected by a professional to identify why elevated nitrate levels are in your well water. You can also consider installing a water treatment system, such as reverse osmosis or distillation units to treat the contaminated water. Before having a system installed, contact your local health department for more information.

In addition to once a year, you should also have your well water tested when:

- The color, taste or odor of your well water changes or if you suspect that someone became sick after drinking well water.

- A new well is drilled or if you have had maintenance done on your existing well

- A flood occurred and your well and/or septic tank were affected

Remember: Bacteria and nitrate are not the only parameters that well water is tested for. Call your local health department to discuss your what they recommend you should get the water tested for, because it can vary depending on where you live.

FDOH maintains an excellent website with many resources for private well users at http://www.floridahealth.gov/environmental-health/private-well-testing/index.html, which includes information on potential contaminants and how to maintain your well to ensure the quality of your well water.

by Rick O'Connor | Jan 21, 2020

There are a couple of things you learn when working with youth in turtle education.

1) ALL turtles are snapping turtles

2) Snapping turtles are dangerous

I grew up in a sand hill area of Pensacola and we found box turtles all of the time. We had one as a “pet” and his name was “Snappy”. Oh, I forgot… all turtles are males.

That said, others are well aware of this unique species of turtle in our state. It does not look like your typical turtle. (1) They are large… can be very large – some male alligator snappers have weighed in at 165 lbs.! (2) Their plastron is greatly reduced, almost not there. Because of this their legs can bend closer to the ground and walk more like dogs than other turtles do. We call this cursorial locomotion. Snappers are not cursorial, but they are close, and because of this can move much faster across land. (3) Their carapace is almost square shaped (versus round or oval) and have large ridges making them look like dinosaurs. (4) They have longer tails than most turtles, some species have scales pointing vertically making them look even more like dinosaurs. Scientists have wondered whether this unique reduced plastron-better locomotion design was the original for turtles (and they lost it), or they are the “new kids on the block”. The evidence right now suggests they are “the new kids”.

The relatively smooth shell of a common snapping turtle crossing a highway in NW Florida.

Photo: Libbie Johnson

And of course, there is the “SNAP”. These are very strong animals who seem to crouch and lunge as they quickly SNAP at potential predators – as quickly as 78 milliseconds/bite. I remember once stopping on a rural highway to get one out of the road. I grabbed it safely behind the nape and near the rear. That sucker crouched and snapped, and I could hardly hold on. I was amazed by its strength. It did not understand I was trying to help. You do need to be careful around these guys.

In Florida, we have two species of snapping turtles; the common and the alligator. They look very similar and are often confused (everyone seen is called an alligator snapper). There are couple of ways to tell them apart.

1) The alligator snapper has a large head with a hooked beak.

2) The alligator snapper’s carapace is slightly squarer and has three ridges of enlarged scales that make it look “spiked”; where the common snapper lacks these.

3) The tail of the common snapper has vertical “spiked” scales; which the alligator lacks.

4) And the textbook range of the alligator snapper is the Florida panhandle. Basically, if you are south or east of the Suwannee River, it should not be around – you are seeing the common.

As the name implies, the common snapper (Chelydra serpentina) is found throughout the state – except the Florida Keys. There are actually two subspecies; the Common (C. serpentia serpentina) which is found west of the Suwannee River and the Florida Snapper (C. serpentina osceola). This species uses a wide range of habitats. They have been found in small creeks, ponds, floodplain swamps, wet areas of pine flatwoods, and on golf courses.

These are very mobile turtles, often seen crossing highways looking for nesting locations, dispersing to new territory, or their pond has just dried up and they need a new one. Interestingly they have an expanded diet. Most think of snapping turtles as fish eaters, but common snappers are known to consume large amounts of aquatic plants and invertebrates.

Like all turtles, snappers must find high-dry ground for nesting. Nesting begins around April and runs through June. In south Florida, nesting can begin as early as February. They select a variety of habitats and typically lay 2-30 eggs deep in the substrate. These incubate for about 75 days and the temperature of the egg determines its sex; warmer eggs produce females. Nest predation is a problem for all turtles, snappers are not exempt from this. Raccoons are the big problem, but fish crows, fox, and possibly armadillos also dig up eggs. Many adults have been found with leeches. Turtles are known to live long lives. Data suggests common snappers reach 50 years of age.

Alligator snappers (Macrochelys temminckii) are the big boys of this group. Where the common snapper’s carapace can reach 1.5 feet, the alligator snapper can reach 2.0. (that’s JUST the shell). As mentioned, this animal is found in the Florida panhandle only. It is a river dweller and prefers those with access to the Gulf of Mexico. They appear to have some tolerance of brackish water. One alligator snapper near Mobile Bay AL had barnacles growing on it. Evidence suggest they do not move as much as common snappers and stay in the river systems where they were born. There are three distinct genetic groups: (1) the Suwannee group, (2) the Ochlocknee/Apalachicola/Choctawhatchee group, and (3) the Pensacola Bay group.

The ridged backs of the alligator snapping turtle. Photo: University of Florida

This animal is more nocturnal than their cousin and are not seen very often. They are basically carnivores and known to feed on fish, invertebrates, amphibians, birds, small mammals, reptiles, small alligators, and acorns are common in their guts. This species possesses a long tongue which they use as a fishing lure to attract prey.

Alligator snappers have a much shorter nesting season than most turtles; April to May. And, unlike other turtles, only lay one clutch of eggs per season. They typically lay between 17-52 eggs, sex determination is also controlled by the temperature of the incubating egg, and they may have strong site fidelity with nesting. Male alligators are very aggressive towards each other in captivity. This suggests strong territorial disputes occur in the wild. These live a bit longer than common snappers; reaching an age of 80 years.

Though still common, both species have seen declines in their populations in recent years. Dredge and fill projects have reduced habitat for the common snapper. Dams within the rivers and commercial harvest have impacted alligator snapper numbers. The alligator snapper is currently listed as an imperiled species in Florida and is a no-take animal (including eggs). Because the common snapper looks so similar, they are listed as a no-take species as well.

Both of these “dinosaur” looking creatures are amazing and we are lucky to have them in our backyards.

References

Meylan P.A. (Ed). 2006. Biology and Conservation of Florida Turtles. Chelonian Research Monographs No.3, 376 pp.

FWC – Freshwater Turtles

https://myfwc.com/wildlifehabitats/wildlife/freshwater-turtles/.