by Laura Tiu | Jun 3, 2017

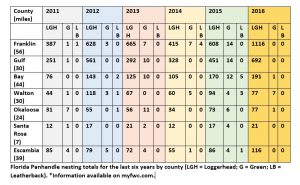

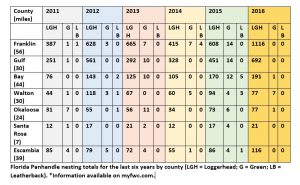

There are five species of sea turtles that nest from May through October on Florida beaches. The loggerhead, the green turtle and the leatherback all nest regularly in the Panhandle, with the loggerhead being the most frequent visitor. Two other species, the hawksbill and Kemp’s Ridley nest infrequently. All five species are listed as either threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act.

Due to their threatened and endangered status, the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission/Fish and Wildlife Research Institute monitors sea turtle nesting activity on an annual basis. They conduct surveys using a network of permit holders specially trained to collect this type of information. Managers then use the results to identify important nesting sites, provide enhanced protection and minimize the impacts of human activities.

Statewide, approximately 215 beaches are surveyed annually, representing about 825 miles. From 2011 to 2015, an average of 106,625 sea turtle nests (all species combined) were recorded annually on these monitored beaches. This is not a true reflection of all of the sea turtle nests each year in Florida, as it doesn’t cover every beach, but it gives a good indication of nesting trends and distribution of species.

If you want to see a sea turtle in the Florida Panhandle, please visit one of the state-permitted captive sea turtle facilities listed below, admission fees may be charged. Please call the number listed for more information.

If you want to see a sea turtle in the Florida Panhandle, please visit one of the state-permitted captive sea turtle facilities listed below, admission fees may be charged. Please call the number listed for more information.

- Gulf Specimen Marine Laboratory, 222 Clark Dr, Panacea, FL 32346 850-984-5297 Admission Fee

- Gulf World Marine Park, 15412 Front Beach Rd, Panama City, FL 32413 850-234-5271 Admission Fee

- Gulfarium Marine Adventure Park, 1010 Miracle Strip Parkway SE, Fort Walton Beach, FL 32548 850-243-9046 or 800-247-8575 Admission Fee

- Navarre Beach Sea Turtle Center, 8740 Gulf Blvd, Navarre, FL 32566 850-499-6774

To watch a female loggerhead turtle nest on the beach, please join a permitted public turtle watch. During sea turtle nesting season, The Emerald Coast CVB/Okaloosa County Tourist Development Council offers Nighttime Educational Beach Walks. The walks are part of an effort to protect the sea turtle populations along the Emerald Coast, increase ecotourism in the area and provide additional family-friendly activities. For more information or to sign up, please email ECTurtleWatch@gmail.com. An event page may also be found on the Emerald Coast CVB’s Facebook page: facebook.com/FloridasEmeraldCoast.

by Andrea Albertin | Apr 29, 2017

One third of homes in Florida rely on septic systems, or onsite sewage treatment and disposal systems (OSTDS), to treat and dispose of household wastewater, which includes wastewater from bathrooms, kitchen sinks and laundry machines. When properly maintained, septic systems can last 25-30 years, and maintenance costs are relatively low.

A conventional residential septic tank and drain field under construction.

Photo: Andrea Albertin

A general rule of thumb is that with proper care, systems need to be pumped every 3-5 years at a cost of about $300 to $400. Time between pumping does vary though, depending on the size of your household, the size of your septic tank and how much wastewater you produce. If systems aren’t maintained they can fail, and repairs or replacing a tank can cost anywhere between $3000 to $10,000. It definitely pays off to maintain your septic system!

The most common type of OSTDS is a conventional septic system, which is made up of a septic tank (a watertight container buried in the ground) and a drain field, or leach field. The septic tank’s job is to separate out solids (which settle on the bottom as sludge), from oils and grease, which float to the top and form a scum layer. The liquid wastewater, which is in the middle layer of the tank, flows out through pipes into the drainfield, where it percolates down through the ground.

Although bacteria continually work on breaking down the organic matter in your septic tank, sludge and scum will build up, which is why a system needs to be cleaned out periodically. If not, solids will flow into the drainfield clogging the pipes and sewage can back up into your house. Overloading the system with water also reduces its ability to work properly by not leaving enough time for material to separate out in the tank, and by flooding the system. Sewage can flow to the surface of your lawn and/or back up into your house.

Failed septic systems not only result in soggy lawns and horrible smells, but they contaminate groundwater, private and public supply wells, creeks, rivers and many of our estuaries and coastal areas with excess nutrients, like nitrogen, and harmful pathogens, like E. coli.

It is important to note that even when traditional septic systems are maintained, they are still a source of nitrogen to groundwater; nitrate is not fully removed from the wastewater effluent.

How can you properly care for your septic system?

Here are a some basic tips to keep your system working properly so that you can reduce maintenance costs by avoiding system failure, and so that you can reduce your household’s impact on water pollution in your area.

- Don’t flush trash down the toilet. Only flush regular toilet paper. Toilet paper treated with lotion forms a layer of scum. Wet wipes are not flushable, although many brands are labelled as such. They wreak havoc on septic systems! Avoid flushing cigarette butts, paper towels and facial tissues, which can take longer to break down than toilet paper.

- Think at the sink. Avoid pouring oil and fat down the kitchen drain. Avoid excessive use of harsh cleaning products and detergents, which can affect the microbes in your septic tank (regular weekly or so cleaning is fine). Prescription drugs and antibiotics should never be flushed down the toilet.

- Limit your use of the garbage disposal. Disposals add organic matter to your septic system, which results in the need for more frequent pumping. Composting is a great way to dispose of your fruit and vegetable scraps instead.

- Take care at the surface of yourtank and drainfield. To work well, a septic system should be surrounded by non-compacted soil. Don’t drive vehicles or heavy equipment over the system. Avoid planting trees or shrubs with deep roots that could disrupt the system or plug pipes. It is a good idea to grow grass over the drainfield to stabilize soil and absorb liquid and nutrients.

- Conserve water. You can reduce the amount of water pumped into your septic tank by reducing the amount you and your family use. Water conservation practices include repairing leaky faucets, toilets and pipes, installing low cost, low-flow showerheads and faucet aerators, and only running the washing machine and dishwasher when full. In the US, most of the household water used is to flush toilets (about 27%). Placing filled water bottles in the toilet tank is an inexpensive way to reduce the amount of water used per flush.

- Have your septic system pumped by a certified professional. The general rule of thumb is every 3-5 years, but it will depend on household size, the size of your septic tank and how much wastewater you produce.

By following these guidelines, you can contribute to the health of your family, community and environment, as well as avoid costly repairs and septic system replacements.

You can find excellent information on septic systems a the US EPA website: https://www.epa.gov/septic. The Florida Department of Health website provides permiting information for Florida and a list of certified maintenance entities by county: http://www.floridahealth.gov/Environmental-Health/onsite-sewage/index.html.

The Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) identified septic systems as the major source of nitrate in Wakulla Springs, located in Wakulla County. Excess nitrate is thought to promote algal growth, leading to the degradation of the biological community in the spring.

Photo: Andrea Albertin

by Rick O'Connor | Apr 14, 2017

The Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill was one of the worst natural disasters in our country’s history.

Photo: Gulf Sea Grant

We are pleased to announce the release of a pair of new bulletins outlining how the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill impacted the popular marine animals dolphins and sea turtles. To read these and other oil spill science publications, go to http://gulfseagrant.org/oilspilloutreach/publications/.

The Deepwater Horizon’s impact on bottlenose dolphins – In 2010, scientists documented a markedly increased number of stranded dolphins in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Was oil exposure to blame? Could other factors have been in play? Read the answers to these questions here: http://masgc.org/oilscience/oil-spill-science-dolphins.pdf.

Sea turtles and the Deepwater Horizon oil spill – This publication reviews the estimated damage oil exposure caused to sea turtles and discusses continued research and monitoring efforts for these already endangered and threatened species. Click here to read this bulletin: http://masgc.org/oilscience/oil-spill-science-sea-turtles.pdf.

Also –

“Sea turtles and oil spills” presentations – On March 23 in Brownsville, Texas, more than 100 participants gathered in person and online to listen to scientists, responders, and sea turtle specialists explain what we know about how these creatures fared in 2010 and detail ongoing conservation programs. Watch videos of the presentations here: http://gulfseagrant.org/sea-turtles-oil-spills/.

Our oil spill science outreach team hopes you will find these resources useful! J

by Laura Tiu | Mar 31, 2017

By: Laura Tiu and Sheila Dunning

For the second year in a row, University of Florida Extension Agents Sheila Dunning (horticulture) and Laura Tiu (marine science) taught a Florida Master Naturalist Program (FMNP) Coastal Module to a newly recruited AmeriCorps group in Okaloosa and Walton counties. The AmeriCorps members have been recruited to work with local the non-profit Choctawhatchee Basin Alliance during the 2016-17 school year teaching Grasses in Classes and Dunes and Schools at the local elementary schools.

AmeriCorp volunteers learning about coastal environments by attending the Florida Master Naturalist class.

Photo: Laura Tiu

As part of the training, FMNP students participated in an aquatic species collection training to enable them to collect species for touch tanks used throughout the school year. At the training, we met two Fort Walton Beach High School science teachers. Teachers Marcia Holman and Ashley Daniels (an AmeriCorps 2013 member herself) were surprised to see two former students in our AmeriCorps 2016 FMNP class; Dylan and Kaitlyn. Dylan, they reported, was a student that many teachers worried about during his freshman year. However, he just blossomed because of his involvement in the marine classes and environmental ecology club. They were most proud of his leadership designing and implementing a no-balloon graduation ceremony. This prevented the release of potentially harmful balloons into our coastal waterways where they pose a hazard to marine life.

The teachers were so happy to see both students had joined AmeriCorps and were receiving FMNP training. They realized that they were making a difference in the lives of their students and the students they had trained were working to preserve and protect the environment in their communities. When asked if they had any other students that we need to be prepared for Holman replied, “It’s hard to tell at this point in the year if we have any rising marine science stars, but we did have 20 kids show up for the first meeting of the ecology kids club.” We can’t wait to meet them.

by Les Harrison | Feb 4, 2017

Valentine’s Day is just a few days away and this month’s theme is evidenced by the color red. Red hearts, bows, roses (imported this time of year from South America) and candy in red boxes

This hue is not frequently seen in Wakulla County in the mist of winter’s grip, but this year azaleas bloomed in January. Still, red highlights in lawns, pastures and other open areas tend to attract attention.

Mature Column Stinkhorns are in striking contrast to most other local mushrooms. These were growing on the edge of the UF/IFAS Wakulla County Extension Demonstration Garden where wood chips are plentiful.

Photo: Les Harrison

The reason is simple. A mushroom species is taking advantage of the cool weather and available moisture.

Clathrus columnatus, the scientific name for the column stinkhorn, is a north Florida native which is common to many Gulf Coast locales. This colorful fungus has also been known by the common name “dead man’s fingers”.

The short lived above ground structure is usually two to six inches high at maturity. This area is known as the fruiting body and produces spores which are the basis for the next generation.

Two to five hollow columns or fingers project upwards above the soil or mulch. Coloration of the fruiting body can range from pink to red, and occasionally orange.

The inner surfaces of the column are covered with stinkhorn slime and spores, and which produces an especially repulsive stench. This foul odor is useful though, attracting an assortment of flies and other insects which track through it.

A small amount of the mixture of the brown slime and spores attaches to the insect’s body. It is then carried by these discerning visitors to other bug enticing spots, usually of equal or greater offensiveness to people. Spores are deposited as the slime mixture is rubbed off as the insects brush against surfaces.

Decaying woody debris is a favorable environment for the column stinkhorn to germinate. As the wood rots bacterial activity makes necessary nutrients available to this mushroom.

Other areas satisfactory for development include lawns, gardens, flower beds and disturbed soils. All contain bits and pieces of decomposing wood and bark.

Occasionally, column stinkhorns can be seen growing directly out of stumps and living trees. Presence on a living tree is a good indication the tree has serious health issues and may soon die.

This fungi starts out as a partially covered growth called a volva. The portion above and below the soils surface has the general appearance of a hen’s egg and is bright white.

The term volva is applied in the technical study of mushrooms, and used to describe a cup-like structure at the base of the fungus. It is one of the precise visible features used to identify specific species.

The cool wet weather currently in Wakulla County combined with local sandy soils and available nutrients create ideal growing conditions. While rarely notices during initial stages of growth, they are quickly spotted at or near maturity.

There are other stinkhorn mushrooms in Wakulla County, but they are not as common. In addition to North America, member of this fungi family with a fetid aroma can be found in Europe, Asia, South America and Australia.

Photo: Les Harrison

While not likely to be a Valentine’s Day gift, it still has a distinct place in the local environment. Get close and it is difficult to overlook.

To learn more about Wakulla County’s mushrooms, contact your UF/IFAS Wakulla Extension Office at 850-926-3931 or http://wakulla.ifas.ufl.edu/

by Les Harrison | Jan 27, 2017

Recent rains have water standing on some Wakulla County real estate, which has been dry for several years. Ponds, natural and dug, are brimming with water reflecting the generous outpouring from the slow and wet weather system, which passed listlessly over the county.

Cypress swamp in Jackson County.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

The rainwater excess is also filling the natural low points known as swamps or wetlands.

A swamp is defined as a forested wetland. Some occur along the flood plain of rivers, where they are dependent upon surplus flow from upstream and from local runoff.

Other swamps appear adjacent to ponds in shallow depressions, which fill during wet periods. Their landscape is covered by aquatic vegetation or trees and plants, which tolerates periodical inundation.

Historically, swamps have an image problem. Legend has all sorts of unsavory creatures, degenerates, and ghost inhabiting the locale waiting for the unsuspecting traveler.

Even the proper British used the term as a pejorative to describe Francis Marion during the American Revolution. The Swamp Fox engaged in guerilla warfare against the conventional forces and hid in the swamps to avoid capture.

Economically, these watery regions have had very low values. Their only significance was as site for trapping, hunting or for logging in dry years.

Medically, swamps were seen as a quick and painful way to the grave. There were all those creatures, which could inflict pain, leeches, snakes, gators and the like.

Then there was disease. As an example, the term Malaria originated from the swamps of southern Europe where it meant bad air in medieval Italian. The mosquito connection was unknown until the early 20th Century.

Hollywood piled on the problem with a series of swamp monster movies. One, “The Creature from the Black Lagoon” was partially filmed at Wakulla Springs.

Reality, as is often the case, is quite different from the initial perception. Even the term swamp has fallen out of favor in some circles, being replaced with wetlands.

Swamps or wetlands serve a variety of functions in the panhandle. Possibly the most critical is as a filtration system for the water table.

Excess rain is held in these shallow depressions and allowed to percolate or filter slowly through the soil. The screening effect of the soil and subsoil layers along with the slow progression cleanses the water of numerous impurities from the surface.

Without the holding capacity of local swamps, most rainwater would end up in streams and rivers. In addition to being a loss for the water table, the excess water would cloud waterways with a glut of surface debris and nutrients.

Large bald cypress trees serve as wildlife habitat at Wakulla Springs State Park. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson

It is true mosquitos favor the still swamp waters, but so do many birds, fish and animals. Swamp rookeries are the nesting home for many wading birds. Mosquito larvae are an important link in the food chain, which supports much of the life in the swamp, and beyond.

Even some of the swamp’s most ostracized residents, snakes, have an important part to play in the overall environmental balance. These reptiles control the population of many destructive insects and rodents.

To learn more about the importance of swamps and wetlands, contact your UF/IFAS County Extension Office.

If you want to see a sea turtle in the Florida Panhandle, please visit one of the state-permitted captive sea turtle facilities listed below, admission fees may be charged. Please call the number listed for more information.

If you want to see a sea turtle in the Florida Panhandle, please visit one of the state-permitted captive sea turtle facilities listed below, admission fees may be charged. Please call the number listed for more information.