by Will Sheftall | Jul 22, 2016

Birds, migration, and climate change. Mix them all together and intuitively, we can imagine an ecological train wreck in the making. Many migratory bird species have seen their numbers plummet over the past half-century – due not to climate change, but to habitat loss in the places they frequent as part of their jet-setting life history.

Migrating songbirds forage for insects in coastal scrub-shrub habitat. Photo credit: Erik Lovestrand, UF IFAS Extension

Now come climate simulation models forecasting more change to come. It will impact the strands of places migrants use as critical habitat. Critical because severe alteration of even one place in a strand can doom a migratory species to failure at completing its life cycle. So what aspect of climate change is now threatening these places, on top of habitat alteration by humans?

It’s the change in weather patterns and sea level that we’re already beginning to see, as the impacts of global warming on Earth’s ocean-atmosphere linkage shift our planetary climate system into higher gear.

For migratory birds, the journey itself is the most perilous link in the life history chain. A migratory songbird is up to 15 times more likely to die in migration than on its wintering or breeding grounds. Headwinds and storms can deplete its energy reserves. Stopover sites for resting and feeding are critical. And here’s where the Big Bend region of Florida figures prominently in the life history of many migratory birds.

According to a study published in March of this year (Lester et al., 2016), field research on St. George Island documented 57 transient species foraging there as they were migrating through in the spring. That number compares favorably with the number of species known to use similar habitat at stopover sites in Mississippi (East Ship Island, Horn Island) as well as other central and western Gulf Coast sites in Alabama, Louisiana, and Texas.

We now can point to published empirical evidence that the eastern Gulf Coast migratory route is used by as many species as other Gulf routes to our west. This confirmation makes conservation of our Big Bend stopover habitat all the more relevant.

The authors of the study observed 711 birds using high-canopy forest and scrub/shrub habitat on St. George Island. Birds were seeking energy replenishment from protein-rich insects, which were reported to be more abundant in those habitats than on primary dunes, or in freshwater marshes and meadows.

So now we know that specific places on our barrier islands that still harbor forests and scrub/shrub habitat are crucial. On privately-owned island property, prime foraging habitat may have been reduced to low-elevation mixed forest that is often too low and wet to be turned into dense clusters of beach houses.

Coastal slash pine forest is vulnerable to sea level rise. Photo credit: Erik Lovestrand, UF IFAS Extension

Think tall slash pines and mid-story oaks slightly ‘upslope’ of marsh and transitional meadow, but ‘downslope’ of the dune scrub that is often cleared for development.

“OK, I get it,” you say. “It’s as if restaurant seating has been reduced and the kitchen staff laid off. Somebody’s not going to get served.” Destruction of forested habitat on our Gulf Coast islands has significantly reduced the amount of critical stopover habitat for birds weary from flying up to 620 miles across the Gulf of Mexico since their last bite to eat.

But why the concern with climate change on top of this familiar story of coastal habitat lost to development? After all, we have conservation lands with natural habitat on St. Vincent, Little St. George, the east end of St. George, and parts of Dog Island and Alligator Point. Shouldn’t these islands be able to withstand the impacts of stronger and/or more frequent coastal storms, and higher seas – and their forested habitat still serve the stopover needs of migratory birds?

Let’s revisit the “low and wet” part of the equation. Coastal forested habitat that’s low and wet – either protected by conservation or too wet to be developed – is in the bull’s eye of sea level rise (SLR), and sooner rather than later.

Using what Lester et al. chose as a reasonably probable scenario within the range of SLR projections for this century – 32 inches, these low-elevation forests and associated freshwater marshes would shrink in extent by 45% before 2100. It could be less; it could be more. Conditions projected for a future date are usually expressed as probable ranges. Experience has proven them too conservative in some cases.

The year 2100 seems far away…but that’s when our kids or grandkids can hope to be enjoying retirement at the beach house we left them. Hmm.

Scientists CAN project with certainty that by the time SLR reaches two meters (six and a half feet) – in whatever future year that occurs, 98% of “low and wet” forested habitat will have transitioned to marsh, and then eroded to tidal flat.

But before we spool out the coming years to a future reality of SLR that has radically changed the coastline we knew, let’s consider where the crucial forested habitat might remain on the barrier islands of the next generation’s retirement years:

It could remain in the higher-elevation yard of your beach house, perhaps, if you saved what remnant of native habitat you could when building it. Or if you landscaped with native trees and shrubs, to restore a patch of natural habitat in your beach house yard.

Migratory songbird stopover habitat saved during beach house construction. Photo credit: Erik Lovestrand, UF IFAS Extension

We’ve all thought that doing these things must be important, but only now is it becoming clear just how important. Who would have thought, “My beach house yard: the island’s last foraging refuge for migratory songbirds!” even in our most apocalyptic imagination?

But what about coastal mainland habitat?

The authors of the March 2016 St. George Island study conclude that, “…adjacent inland forested habitats must be protected from development to increase the probability that forested stopover habitat will be available for migrants despite SLR.” Jim Cox with Tall Timbers Research Station says that, “birds stop at the first point of land they find under unfavorable weather conditions, but also continue to migrate inland when conditions are favorable.”

Migratory birds are fortunate that the St. Marks Refuge protects inland forested habitat just beyond coastal marshland. A longer flight will take them to the leading edge of salty tidal reach. There the beautifully sinuous forest edge lies up against the marsh. This edge – this trailing edge of inland forest – will succumb to tomorrow’s rising seas, however.

Sea level rise will convert coastal slash pine forest to salt marsh. Photo credit: Erik Lovestrand, UF IFAS Extension

As the salt boundary moves relentlessly inland, it will run through the Refuge’s coastal buffer of public lands, and eventually knock on the surveyor’s boundary with private lands. All the while adding flight miles to the migration journey.

In today’s climate, migrants exhausted from bucking adverse weather conditions over the Gulf may not have enough energy to fly farther inland in search of forested foraging habitat. Will tomorrow’s climate make adverse Gulf weather more prevalent, and migration more arduous?

Spring migration weather over the Gulf can be expected to change as ocean waters warm and more water vapor is held in a warmer atmosphere. But HOW it will change is difficult to model. Any specific, predictable change to the variability of weather patterns during spring migration is therefore much less certain than SLR.

What will await exhausted and hungry migrants in future decades? Our community decisions about land use should consider this question. Likewise, our personal decisions about private land management – including beach house landscaping. And it’s not too early to begin.

Erik Lovestrand, Sea Grant Agent and County Extension Director in Franklin County, co-authored this article.

by Rick O'Connor | Jun 10, 2016

I have played in the waters of the northern Gulf of Mexico all of my life… but I have never heard of this – “sea lice.” It has been in the news recently and I have had a couple inquiries concerning it so I decided to investigate.

A few weeks ago there was a report of “sea lice” in Walton County. Bathers were leaving the water with a terrible skin condition that was itchy and painful, particularly in areas beneath their bathing suits. Photos of this show a series of welts over the area – almost like a rash. What was causing it? And what can you do about it?

Illustration of the “thimble jellyfish”.

Graphic: University of Michigan

My first stop was Dr. Chris Pomory, an invertebrate zoologist at the University of West Florida. Dr. Pomory indicated that the culprit was most probably the larva of a small medusa jellyfish called the thimble jellyfish (Linuche unguiculata), though he included that it could be caused by the larva any of the smaller medusa. Dr. Maia McGuire, Florida Sea Grant, told me a colleague of hers was working on this issue when she was in grad school at the University of Miami. Published in 1994, it too pointed the finger at the larva of the thimble jellyfish. Here I found the term “Sea Bathers Eruption” (SBE) associated with occurrences of this. I also found another report of SBE from Brazil in 2012 – once again pointing the finger at the thimble jellyfish larva. So there you go… the most probable cause is the larva of the thimble jellyfish. Note here though… Dr. McGuire indicated that SBE was something that was problematic in south Florida and the Caribbean… reports from the northern Gulf are not common.

So what is this “thimble jellyfish”?

Most know what a jellyfish is but many may not know there are two body forms (polyp and medusa) and may not know about their life cycles. The classic jellyfish is what we call a medusa. These typically have a bell shaped body and, undulating this bell, swim through the water dragging their nematocyst-loaded tentacles searching for food. Nematocysts are small cells that contain an extendable dart with a drop of venom – this is what causes the sting. Nematocysts are released by a triggering mechanism which is stimulated either by pressure (touch) or particular chemicals in the water column – hence the jellyfish cannot actually fire it themselves. The thimble jellyfish are dioecious, meaning there are male and females, and the fertilized eggs of the mating pair are released into the ocean. These young develop into a larva called planula, and these seem to be the source of the problem. Drifting in the water column they become entrapped between your skin and your bathing suit where the pressure of the suit against the skin, especially after leaving the water, causes the nematocyst to fire and wham – you are stung… multiple times. The planula larva are more common near the surface so swimmers and snorkelers seem to have more problems with them.

So what can be done if you encounter them?

Well – there are two schools of thought on this. (1), go ahead and stimulate the release of all nematocysts on your body and get it over with or (2) do everything you can to keep any more nematocysts from “firing”. Some prefer #1 – they will use sand and rub over the area where the jellyfish larva are. This will trigger the release of any unfired nematocyst, you will deal with the pain, and it will be over. However, you should be aware that many humans have a strong reaction to jellyfish stings and that firing more nematocysts may not be in your best interest. Some will want to take a freshwater shower to rinse them off. This too will trigger any unfired nematocysts and you will be stung yet again. Using vinegar will have the same response as freshwater.

So what do you if you DO NOT to get stung more? Well… the correct answer is to get the bathing suit off and rinse in seawater that DOES NOT contain the larva… easier said than done – but is the best bet.

Is there any relief for the pain and itch?

Dr. McGuire provided the following:

Once sea bather’s eruption occurs (and you have taken off your swimsuit and showered), an application of diluted vinegar or rubbing alcohol may neutralize any toxin left on the skin. An ice pack may help to relieve any pain. The most useful treatment is 1% hydrocortisone lotion applied 2-3 times a day for 1-2 weeks. Topical calamine lotion with 1% menthol may also be soothing. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen and aspirin (but not in children) may also help to reduce pain and inflammation. If the reaction is severe, the injured person may suffer from headache, fever, chills, weakness, vomiting, itchy eyes and burning on urination, and should be treated with oral prednisone (steroids). The stinging cells may remain in the bathing suit even after it dries, so once a person has developed sea bather’s eruption, the clothing should undergo machine washing or be thoroughly rinsed in alcohol or vinegar, then be washed by hand with soap and water. Antihistamines may also be of some benefit. Other treatments that have been suggested include remedies made with sodium bicarbonate, sugar, urine, olive oil, and meat tenderizer although some of these some may increase the release of toxin and aggravate the rash. Symptoms of malaise, tummy upsets and fever should be treated in the normal fashion.

This is a “new kid on the block” for those of us in the northern Gulf. It has been in south Florida and the Caribbean for a few decades. As the Gulf warms, more outbreaks may occur, there is really not much to be done about that. Hopefully most reactions will be minor, as with any other jellyfish sting.

For more information visit the Florida Department of Health.

by Laura Tiu | Apr 22, 2016

The Deepwater Horizon (DWH) oil spill occurred about 50 miles offshore of Louisiana in April 2010. Approximately 172 million gallons of oil entered the Gulf of Mexico. Five years after the incident, locals and tourists still have questions. This article addresses the five most common questions.

QUESTION #1: Is Gulf seafood safe to eat?

Ongoing monitoring has shown that Gulf seafood harvested from waters that are open to fishing is safe to eat. Over 22,000 seafood samples have been tested and not a single sample came back with levels above the level of concern. Testing continues today.

QUESTION #2: What are the impacts to wildlife?

This question is difficult to answer as the Gulf of Mexico is a complex ecosystem with many different species — from bacteria, fish, oysters, to whales, turtles, and birds. While oil affected individuals of some fish in the lab, scientists have not found that the spill impacted whole fish populations or communities in the wild. Some fish species populations declined, but eventually rebounded. The oil spill did affect at least one non-fish population, resulting in a mass die-off of bottlenose dolphins. Scientists continue to study fish populations to determine the long term impact of the spill.

Question #3: What cleanup techniques were used, and how were they implemented?

Several different methods were used to remove the oil. Offshore, oil was removed using skimmers, devices used for removing oil from the sea’s surface before it reaches the coastline. Controlled burns were also used, where surface oil was removed by surrounding it with fireproof booms and burning it. Chemical dispersants were used to break up the oil at the surface and below the surface. Shoreline cleanup on beaches involved sifting sand and removing tarballs and mats by hand.

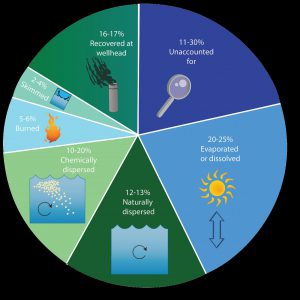

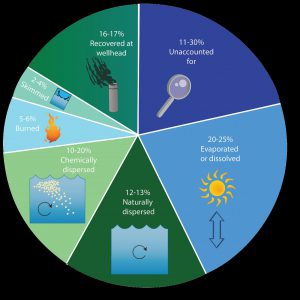

QUESTION #4: Where did the oil go and where is it now?

The oil spill covered 29,000 square miles, approximately 4.7% of the Gulf of Mexico’s surface. During and after the spill, oil mixed with Gulf of Mexico waters and made its way into some coastal and deep-sea sediments. Oil moved with the ocean currents along the coast of Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida. Recent studies show that about 3-5% of the unaccounted oil has made its way onto the seafloor.

QUESTION #5: Do dispersants make it unsafe to swim in the water?

The dispersant used on the spill was a product called Corexit, with doctyl sodium sulfosuccinate (DOSS) as a primary ingredient. Corexit is a concern as exposure to high levels can cause respiratory problems and skin irritation. To evaluate the risk, scientists collected water from more than 26 sites. The highest level of DOSS detected was 425 times lower than the levels of DOSS known to cause harm to humans.

For additional information and publications related to the oil spill please visit: https://gulfseagrant.wordpress.com/oilspilloutreach/

Adapted From:

Maung-Douglass, E., Wilson, M., Graham, L., Hale, C., Sempier, S., and Swann, L. (2015). Oil Spill Science: Top 5 Frequently Asked Questions about the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. GOMSG-G-15-002.

An estimate of what happened to approximately 200 million gallons oil from the DWH oil spill. Data from Lehr, 2014. (Florida Sea Grant/Anna Hinkeldey)

The Foundation for the Gator Nation, An Equal Opportunity Institution.

by Rick O'Connor | Apr 8, 2016

This gopher tortoise was found in the dune fields on a barrier island – an area where they were once found.

Photo: DJ Zemenick

The state of Florida has designated Sunday April 10 as “Gopher Tortoise Day”. The objective is to bring awareness to this declining species and, hopefully, an interest in protecting it.

During his travels across the southeast in the late 18th century, William Bartram mentioned this creature several times. As he walked through miles of open longleaf pine he would climb sand hills where he often encountered the tortoise. These turtles do like high dry sandy habitats. Here they dig their famous burrows into the earth.

These burrows can extend almost 10 feet vertically below the surface but, being excavated at an angle, can extend 20 feet in length. There is only one entrance and the tortoise works hard to maintain it. Field biologists have been able to identify over 370 species of upland creatures that utilize these burrows as refuge either for short or long periods of time. These include the declining diamondback rattlesnakes, gopher frogs, and the endangered indigo snakes, but most are insects and small mammals. Because of the importance of the burrows to these species, gopher tortoises are listed as keystone species – meaning their decline will trigger the decline of the others and can upset the balance of the ecosystem. Gopher burrows can be distinguished from mammal burrows in that they are domed across the top but flat along the bottom, as opposed to being oval. The width of the burrow is close to the length of the tortoise. When danger is encountered the tortoise will turn sideways – effectively blocking the entire entrance. Though there are cases of multiple tortoises in one, the general rule is one tortoise per burrow.

Tortoises are herbivores, feeding on a variety of young herbaceous shoots, and fruit when they can get find them. Fire is important to the longleaf system and it is important to the gophers as well. Fires encourage new young shoots to sprout. If an area does not receive sufficient fire, and the ground vegetation allowed grow larger with tougher leaves, the tortoise will abandon their burrow and seek more suitable habitat – which, especially in Florida – is becoming harder and harder to find. They typically breed in the fall and will lay their 5-10 eggs in the loose sand near the entrance of the burrow in spring. In August the hatchlings emerge and may hide beneath leaf litter, but will quickly begin their own burrows.

This tortoise is only found in the southeast of the United States and it is in decline across the region. They are currently listed as threatened in Florida but are federally protected in Louisiana, Mississippi, and western Alabama. They are found across our state as far south as the Everglades. There are several reasons why their numbers have declined. Human consumption was common in the early parts of the 20th century, and still is in some locations – though illegal. Some would, at times, pour gasoline down the burrow to capture rattlesnakes – this of course did not fare well for the tortoise. A big problem is the loss of suitable habitat. Much of upland systems require periodic fires to maintain the reproductive cycle of community members. The suppression of fire has caused the decline of many species in our state including gopher tortoises. These under maintained forest have forced tortoises to roadsides, power line fields, airports, and pastures. In each case they have encountered humans with cars, lawn mowers, and heavy equipment. Keep in mind also that our growing population is forcing us to clear much of these upland habitats for developments where clearing has caused the burial (entombment) of many burrows.

This is a unique turtle to our region and honestly, is a pleasure to see. We hope you will take the time to learn more about them by visiting FWC’s Gopher Tortoise Day website, enjoy watching them if they live near you, and help us conserve this species for future generations.

by Rick O'Connor | Mar 25, 2016

All Photos: Molly O’Connor

In this monthly series of highlighting outdoor adventures in the Florida Panhandle, we are visiting locations along the Intracoastal Waterway; from the Alabama State line to the Aucilla River. In January we wrote about Perdido Key, last month we visited Pensacola Beach, this month we move east along Santa Rosa Island to the beach community of Navarre.

Navarre Beach is a relatively quiet community on Santa Rosa Island between Pensacola and Ft. Walton Beach. There are some good places to eat, a new RV campground, and plenty of water/outdoor activities. Navarre Beach became famous in the 1970’s as the location for the film Jaws II. I personally witnessed much of the shooting of the film and it was amazing to see how it all actually all works. The hotel that was used in the film is no longer there but the stories are!

On the Island

There are some great kayak and paddle locations on Navarre Beach. Paddling over the grassbeds and to the east of the Navarre Marine Park you can see a lot of coastal wildlife and great sunsets. You can of course paddle the Gulf as well and maybe take a shot at kayak fishing. You will find local kayak rentals and guides by visiting Naturally EscaRosa website.

Paddling in a kayak or on a paddleboard is a great way to view wildlife and natural scenes while visiting Navarre Beach.

The Navarre Fishing Pier extends over 1500 feet. Not only a great place to fish but a great place to view marine life.

Speaking of fishing, there is the Navarre Beach Fishing Pier which extends 1500 feet out over the Gulf. The pier provides of variety of price options for fishermen of all ages and for $1 you can just walk and enjoy the view. Sharks and sea turtles are often seen from here – and don’t forget the sunsets.

There are two educational interpretive centers on Navarre Beach. The Navarre Beach Marine Science Station is part of the Santa Rosa County School District. They provide programs for elementary, secondary, and dual-enrolled high school-college students. The Station also provides numerous youth camps during the school year and during the summer, as well as providing activities at local community events. To see if they have something going for your young one while you are here visit their website.

The Navarre Beach Marine Science Station provides education for young and old.

The Navarre Beach Sea Turtle Conservation Center is an educational center that focuses on imperiled marine wildlife but the sea turtle is the star of the show. The center will eventually house an injured sea turtle that can no longer be released but until one arrives, there is plenty to see and learn. Learn more about the center at their website.

The Navarre Beach Sea Turtle Conservation Center.

Santa Rosa County also provides a couple of nearshore snorkel reefs for the public. You can find them on both the Gulf and Sound sides.

These day markers are marking two nearshore snorkel reefs on the Sound side of Navarre Beach. They can be accessed from the Navarre Marine Park.

A barge travels beneath the Navarre Beach Bridge as it heads east along the ICW.

Off the island

Actually, you have to leave Santa Rosa at this point. The island between Navarre Beach and Ft. Walton Beach is the property of the United States Air Force.

As you leave Navarre Beach to travel the ICW from the north side, you see the Panhandle Butterfly House on your left at the Highway 98 traffic light. This is a great stop. Viewing live butterflies feeding on native plants in all stages of their lives is a cool sight. There are plenty of volunteers to educate you about native butterflies and there is a pond out back with a lot of turtles and birds to view. It’s a neat and relaxing place.

The Panhandle Butterfly House is located just to the west of the traffic light on Highway 98 as you leave Navarre Beach.

Numerous turtles can be found swimming and basking in the pond behind the butterfly house.

A snowy egret hunts for a meal in the turtle pond behind the butterfly house.

Nature Notes: Sea Turtles

Who doesn’t love sea turtles! These silent, charismatic creatures have been navigating Gulf waters, and nesting on our beaches for centuries. Certainly the largest species of turtle humans will encounter, weighing in between 200-300 pounds – with some reaching 1000 pounds, they are an awesome thing to see. There are five species found in the northern Gulf of Mexico and there are records of four them nesting here. Those species are the Loggerhead, Green, Kemp’s Ridley, Hawksbill, and the giant of them all the Leatherback.

Sea turtles begin their lives within the egg buried on a beach. The sex of the embryo is determined by the temperature of the sand they are incubating in – cold ones become males and 29°C appears to be the cutoff. After 60-70 days incubating the young hatchlings emerge at night and orient towards shortwave light (moon or stars off the water). However, in recent years much of the light we provide in our homes as directed them in the wrong direction (disorientation). There are “turtle friendly lights” that use longwave colors and significantly reduce the disorientation problem. All coastal counties along the panhandle require these lights for island structures. Many of the hatchlings are lost as they wonder to the Gulf. Ghost crabs, fox, coyotes, and now feral cats capture and consume many.

Those lucky enough to reach the water now have to deal with fish and bird predators. These young head offshore seeking the Sargassum mats where they will spend their growing years feeding and hiding.

As immature adults most species will return to the coastal areas to feed on seagrasses or invertebrates. As they become sexually mature they, once again, head to sea. Though they travel far and wide they are known to return to their place of birth for breeding and egg laying. Breeding takes place just offshore and females may come ashore more than once to deposit their clutch of 100+ eggs.

In addition to light pollution, marine debris, boat strikes, commercial fishing nets, and even holes and chairs left on the beach overnight have caused their numbers to decline. You should be aware that most coastal counties have a “leave no trace” ordinance asking you to remove your chairs, tents, and other items at the end of the day – and please fill in any holes you may have dug. All species of marine turtles are currently listed and protected by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. In Florida, the USFWS has yield management of these species to the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. They are truly a magnificent creature and we hope all get to see one while exploring our beaches.

Now it is time to move to Okaloosa County – the April issue will look at Ft. Walton and Destin. Let’s head there and see what cool outdoor adventures await us.

You can find information on ecotourism providers in Escambia and Santa Rosa counties by visiting Naturally EsacRosa.

by Sheila Dunning | Mar 12, 2016

With all the news about the Zika virus spread in Florida, now is the time to start thinking about mosquito protection. As the weather warms, they will be hatching. Check out where the water is collecting in your yard. The female Aedes aegypti mosquitoes lay their eggs in temporary flood water pools; even very small ones such as pet watering bowls, bird baths and upturned Magnolia or Oak leaves. Dumping out the collection containers and raking through the leaves every couple of days can greatly reduce the population.

With all the news about the Zika virus spread in Florida, now is the time to start thinking about mosquito protection. As the weather warms, they will be hatching. Check out where the water is collecting in your yard. The female Aedes aegypti mosquitoes lay their eggs in temporary flood water pools; even very small ones such as pet watering bowls, bird baths and upturned Magnolia or Oak leaves. Dumping out the collection containers and raking through the leaves every couple of days can greatly reduce the population.

Becoming infected with Zika virus is not common. Though the disease can be transmitted by mosquitoes, blood transfusions or sex, the only know infections in Florida were from people who had been “bitten” by mosquitoes while travelling to countries with active virus outbreaks. That is until this past week, when a person-person infection occurred between a man that had been infected while out of the country and the woman he returned to in Florida. Mosquitoes usually obtain the virus by feeding on infected people, who may not exhibit any symptoms because they have been exposed and their body has built an immunity to the virus. Once the mosquito has drawn infected blood from the person, the infected mosquito “bites” another human, transmitting the virus mixed in saliva into the blood stream of the second host. If the second host is a susceptible pregnant woman, there is a risk of birth defects for the unborn child. If the infected host is a man, he can transmit the virus in semen for about two weeks.

Government public health officials here in Florida are able to monitor mosquito-borne illnesses quickly and effectively. Though the daily news can be alarming, the awareness is truly the message.

To protect yourself and reduce the sources for mosquitoes to breed, here are a few pointers:

Stay indoors at dusk (peak mosquito biting time).

If you must be outside, wear long sleeves and pants and/or mosquito repellents containing the active ingredient DEET.

Repair torn door and window screens.

Remove unnecessary outside water sources.

Flush out water collected in outdoor containers every 3-4 days.

Disturb or remove leaf litter, including roof gutters and covers on outdoor equipment.

Apply larvicides, such as Bacillus thuriengensis israelensis (BTI) to temporary water holding areas and containers.

The mosquitoes have been around all winter with the milder weather and frequent rain. As spring approaches they will be laying eggs on all the water surfaces they can find. As you venture out into the yard or travel to the great outdoors, remember to protect yourself and look at all the ways you can remove the potential habitats for the pesky creatures.