by Rick O'Connor | Sep 25, 2015

In the last edition in this series we discussed some of the issues and problems our estuaries are facing. For the final edition for National Estuaries Week we want to leave you with some ideas on you can help improve things.

The first issue we dealt with was eutrophication – or nutrient overloading. The primary nutrient we have issues with in this part of the panhandle is nitrogen. Nitrates can converted from other forms of nitrogen and can be discharged directly into the water. Common sources are leaf litter, animal waste, commercial fertilizers, and human sewage. Most of this is discharged into our waters via stormwater runoff. This runoff occurs from our properties (due to the lack of natural vegetation holding it) and from stormwater drains (where it is directed through our engineering projects).

One method of dealing with this problem is restoring the shoreline back to its natural state. This is called Living Shorelines and they are being restored all over the country. In most cases locally Living Shorelines would be restoring salt marshes to our shorelines. There are some issues with this. It lessens the amount of open beach you have to enjoy. You have to purchase special plants to do this, and it may require a permit from the state of Florida. Permits are required only if you are planting at or below the mean high tide line; all submerged lands are actually the property of the state of Florida. Permits for Living Shorelines can be obtained from the Florida Department of Environmental Protection.

FDEP planting a living shoreline on Bayou Texar in Pensacola.

Photo: FDEP

The first question you would want to ask when considering a Living Shoreline for your property is whether there was a salt marsh along your shore historically. Salt marshes require low energy beaches to establish themselves and your location may not be such. If you are not sure you can contact the Sea Grant Agent in your county to provide assistance with that determination. If you feel your property would support a Living Shoreline then you will need a permit. There is the “long form” and the “short form” permit. The “short form” obviously what you want and it costs less also. However certain criteria must be met in order to be exempt from the “long form”. To determine whether you are exempt from the “long form” visit https://www.flrules.org/gateway/RuleNo.asp?title=ENVIRONMENTAL%20RESOURCE%20PERMITTING&ID=62-330.051 Click “view rule” and scroll down to (12)(e). If you feel that you qualify for the exemption then it is as simple as completing the form and submitting your check. You should have your permit in just a few weeks. If you do not qualify then it is recommended that you contact the Florida Department of Environmental Protection for advice on moving forward. (850) 595-8300.

Whether you qualify for a Living Shoreline or not – or even if you do not live on the water – there is a landscaping program that you can adopt that will help a lot. It is called Florida Friendly Landscaping. This UF/IFAS program helps homeowners select the “right plant for the right place”. Basically the idea is to landscape your yard with native plants that require little or no fertilizing or water. Not only does this program help our estuaries it saves the homeowner money. One of the first things you will want to do when planning a Florida Friendly Landscape is have your soil tested. The county extension office provides this service for about $7. If interested contact your county extension office about where to pick up the soil testing sample bags. Rain barrels and rain gardens are also good ways to reduce water runoff and save water for those times when you might need it. A trickle hose connected to a rain barrel can reduce runoff and your water bill.

Florida Friendly Landscaping involves using native plants that require less water and fertilizer.

Photo: Southwest Florida Water Management District

We are not certain how much of the animal waste is in fact human but we do know that much of the human waste is from septic tanks. If you have a septic tank – maintain it. Most of the problems come from those that are not maintained well. If you can connect to a sewer line we recommend you do this. The sewer is not without its problems but the problems are much reduced. If you own a pet – clean up behind them.

The leaf litter problem is just that… a problem. Within the city limits many municipalities will collect your yard waste. In Pensacola they do so using a large “claw” however this claw leaves large holes in your yard – so people place the yard waste in the street. Doing this encourages runoff into the bay and the problems we have already discussed. So many will bag it. In Escambia County the yard waste is converted into mulch and is free to the public. However if the yard waste is placed in plastic bags they cannot do this. It’s tough problem. One answer is to develop your own compost pile and dispose of your yard waste there. Your county extension office can help you with different methods of composting and help you select the method that is best for you.

A commercial composting bend that can purchased at many locations or on line.

Photo: UF/IFAS

Composting bends can also be made from recycle materials such as pallets.

Photo: UF/IFAS

All of these suggestions about can reduce nutrients and bacteria in our waterways that contribute to fish kills and health advisories. It will reduce turbidity, which will help seagrasses, and actually Living Shorelines can reduce shoreline erosion.

These same practices can not only improve water quality they could help restore some of our declining fisheries. Living Shorelines provide needed habitat for many commercial and recreational valuable species. As mentioned, these projects will remove much of the sediment improving water clarity to a point where seagrasses can restore themselves and who knows… maybe the scallop will return. On the subject of scallops, Florida Sea Grant conducts scallops surveys in some of panhandle estuaries in the summer. You can volunteer to be a scallop surveyor and assist with data collection that could support a scallop restoration projects. When fishing follow the regulations. They may seem unfair and out dated but know that fisheries managers are trying to get it right and your cooperation will certainly help develop a sustainable fishery for years to come.

The issue of garbage is another tough one. We have been conducting educational programs for decades trying to reduce the amount of solid waste – it’s still there. Many of the local residents are pretty good at taking their trash with them and recycling monofilament fishing line… but not all. Encourage your friends to “take it with them” and “leave no trace” when they go home each day. Out of town visitors can be a problem. Local education from all of us should help some. Participate in one of the CleanPeace’s Ocean Hours. If in the Santa Rosa and Escambia area contact the Sea Grant Agents from those counties for more information. If from another county, contact your local county extension office for information on beach clean ups.

A sea turtle entangled in a discarded fishing net.

Photo: NOAA

Our estuaries have improved significantly from where they were in the late ‘60’s and early 70’s. A little on our part now we can improve them even more. We hope you have learned something new about your local estuary during National Estuaries Week. We hope you will take the time to enjoy these great bodies of water and do what you can to protect for future years.

by Rick O'Connor | Sep 24, 2015

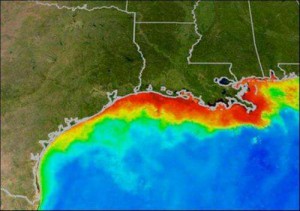

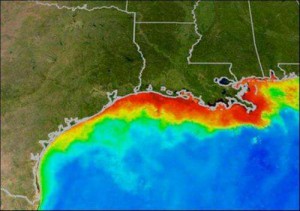

The red area indicates where dissolved oxygen levels are low.

I don’t want this to sound like a “Debbie Downer”… but there are problems with our estuaries and panhandle residents should be aware of them. There are things you can do to correct them – which we will discuss in the final issues of this series – but you need to understand the problem to be able to solve it. Unfortunately there are many issues and problems our bays and bayous face and we do not have time in this short article to discuss them all, but we will discuss some.

We’ll start at the top… with our rivers. Since the founding of our nation many communities were built on estuaries; those that were not were built on the rivers. Water was an easy way to move throughout the country – much easier than wagon crossing over the Appalachians or through a bog. There are several communities that developed along the rivers that feed the panhandle bays. Though the situation has improved in the last few decades, most of these communities have used these rivers as a place to dump their waste. Assorted chemicals, sewage, and solid waste were discharged… and it all came down to us. The Mississippi River is an example of this problem. Discovered in the 1990’s the Louisiana Dead Zone is an area in the Gulf where the levels of dissolved oxygen are so low that little or no life can be found on the ocean floor there. It is believed to be trigger by nutrients, chemical fertilizers and animal waste, being discharged upstream. These nutrients create a bloom of plankton, which can darken the water. Though the phytoplankton can produce oxygen during the daylight hours, they consume it in the evening, lowering the concentration of dissolved oxygen within the water column. The plankton are relatively short lived and eventually die. As the dead plankton fall out to the seafloor bacteria begin to decompose their bodies thus dropping the dissolved oxygen levels further. When the dissolved oxygen concentrations drop below 4.0 millgrams/liter we say the water is hypoxic (low in oxygen). Many species of aquatic organisms begin to stress. At 2.0 mg/L many species will die and we have a “dead zone”. If it reaches 0.0 mg/L we say the water is anoxic (without oxygen). This process is called eutrophication and not only a problem at the mouth of the Mississippi River, it occurs in almost all of the bays and bayous of the panhandle and is the primary cause of local fish kills.

A more recent issue with our rivers has been the reduction of water. In the so called “Water Wars” the state of Georgia has used its damn system to block the flow of the Chattahoochee River to create electricity and a reservoir of drinking water for river communities. Under normal conditions this has not created a problem however in recent years the southeast has experienced drought and the state of Georgia has had the need to hold back water for large communities – such as Atlanta. This has reduced the amount of water flowing towards the Gulf and has impacted communities all along the way. It is not the only issue but is the primary factor triggering the collapse of the oyster industry in Apalachicola. The reduced freshwater flow has increased salinities in the bay. This has disrupted the life cycle of the eastern oyster and has increased both predation and disease within these populations. Apalachicola produces over 90% of Florida’s oysters and 10% of the oysters for the entire country! Oysters are a huge industry in this town. Many are oystermen and many others process the product when it is landed… the industry is on the verge of collapsing. (Learn more).

Oysterman on Apalachicola Bay.

Photo: Sea Grant

These are just some the issues stemming from the rivers… what about the issues initiated from the communities that live along the bay…

How about the seafood? We discussed the oyster industry in Apalachicola Bay but oyster production in other local bays has declined as well (for other reasons). Scallops are gone from many of their historic estuaries, shrimp and blue crab landings are down, this year mullet seem to be hard to find. What is going on here? For the most part the decline in seafood products can be tied to either a decline in water quality or from over harvesting. The harvesting issue is easy… do not harvest as much. However these fisheries management decisions impact many lives and has caused a lot of debate. First you need to determine whether the decline is due to overharvesting or some other environmental factor… easier said than done. Certainly the biology of your target species will give you an idea of how many animals you can remove from the system and sustain a healthy population (maximum sustainable yield) but this method has triggered debate as well. Most fishermen do not want to see the fishery collapse and are willing to work with fishery managers to assure this – but they do have bills to pay. Fishery managers have a responsibility to assure the fishery remain for current and future generations of fishermen and they are basing their decisions on the best available science. It is a touchy subject for many and a problem within our estuaries.

The other cause of declining seafood is poor water quality. You can talk to any “ole timer” and they will tell you about the days when the water was clearer, the grass was thicker, and the fish were more abundant… what happen? I spoke with my father-in-law before he passed away about the changes he saw in Bayou Texar in Pensacola. He remembers being able to see the bottom, more seagrass, and being able to catch a variety of finfish as well as shrimp the size of your hand. The first change he remembered was a change in water clarity… it became murkier… and this happen about the time they began to develop the east side of the bayou. As our communities grew more land was cleared for development. The cleared land allowed more runoff to reach the creeks, bayous, and bays. Infrastructure had to be placed to reduce flooding of yards and streets – Bayou Texar has 38 storm drains. All of this led to more runoff into our water ways. With the increase in turbidity the amount of sunlight reaching the bottom was reduced and seagrasses began to decline. Many species of seagrass require salinities of 25 parts per thousand or higher and the increase in freshwater runoff lowered the salinity which also stressed these grasses. Much of this runoff included sand and silt and the grasses were basically buried. All in all seagrasses declined… and with them many of the marine creatures. Salt marshes were removed for coastal developments, industries were located on our rivers and bays and introduced their chemical discharge, and boating activity increased… our estuaries were being literally “loved to death”. I have seen in my lifetime the decline of sea urchins and scallops from our bay, the increase in turbidity, and the decline of seagrasses. But we cannot blame all of this on habitat loss and pollution. Speaking recently with fisheries managers they believe the recent decline in blue crab landings is due to drought. Reduction in rainfall means reduction in river discharge, which means an increase in salinity and a disruption of the crab reproductive cycle.

Power plant on one of the panhandle estuaries.

Photo: Flickr

Another problem that is associated with runoff has been the increase in bacteria. Fecal coliform bacteria are found in the stomachs of birds and mammals. They assist with our digestion and are released into the environment whenever we (or they) go to the bathroom. So finding fecal coliforms in the water is not unusual… the problem is TOO many fecal coliforms. As mentioned coliforms are not a threat to us but they are used as an indicator of how much waste is in the water. Feces harbors many other microbes in addition to coliforms – hepatitis and cholera outbreaks have been linked to sewage in the water. So agencies monitor for these each week. Most agencies will monitor for E. coli when sampling freshwater and Enterococcus in saline waters. E. coli values of 800 colonies / 100 milliters of sample or higher, and Enterococcus values of 104 colonies / 100 ml of sample will trigger a health advisory being issued – and some bodies of water being closed. In the Pensacola area the Florida Department of Environmental Protection and the Escambia County Health Department both monitor for bacteria. They post their results each week and I, in turn, post to the community. Our local bayous are averaging between 8-10 advisories each year. The problem with these advisories is that residents who live on the waterways, businesses (such as hotels and ecotours) who use the waterways become concerned about entering the water. It is not good for business or property values if the body of water you are on has high levels of bacteria and signs posting “no swimming”.

Closed due to bacteria.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

There are many problems our estuaries are facing but for this article we will end with solid waste. Trash and garbage has been a problem since I can remember. Campaigns have been launched each decade to try and reduce the problem but the problem still exist. Plastics and monofilament litter the beaches and waterways creating problems for marine life and an “eye soar” for those enjoying the bay. I am currently working with the Wildlife Sanctuary of Northwest Florida and CleanPeace to monitor solid waste in Pensacola Bay. Each week CleanPeace host a Saturday event they call “Ocean Hour” where they select a location on the bay and clean for an hour. They submit the top three items to me each week and have been doing this since January… it has been pretty consistent… cigarette butts, plastic food wrappers, and plastic drink containers. We are not going to get rid of garbage on our beaches but if we can consistently reduce the “top three” we should be able to reduce the problem.

More on what we can do to help in the final issue.

by Rick O'Connor | Sep 23, 2015

This area along Florida’s east coast is experiencing coastal flooding.

Photo: University of Florida

As we come towards the end of National Estuaries Week we will now look at some issues our estuaries are facing. Sea level rise is one that generates a variety of responses from the public. For some it is of concern, something we need to be planning for and need to spend more research dollars on to improve our models to understand it. For others, it is a problem for the back burner; yea, it is happening but the changes are over a long period of time and the serious impacts will not occur for a while – and we have more pressing issues to deal with. The old “it’s not a problem until it’s a problem” form of planning. Others still understand it but do not believe the models and do not believe the impacts will be very serious – thus warrants little or no planning. And there are those who do not believe climate change and sea level rise is actually occurring. They see no tangible evidence of any changes. Each year feels like the last – it just is not happening.

A couple of years ago I was part of a team that conducted a series of focus group meetings with residents and businesses who live and work on our barrier islands. The focus of the discussion was to determine what the coastal residents were most concerned about in terms of climate change, sea level rise, and coastal resiliency. The majority of the participants did not deny climate change but were not concerned about planning for it at this time; they had other issues were more pressing… like coastal flooding and the national flood insurance plan – which plans to increase rates for properties in flood prone areas. Ironically, this issue is tied to climate change and sea level rise. They were more concerned about it than they realized. And we did have a few who asked the question – “is there any science that supports the notion of climate change?” Let’s start there… is there any science to support this?

Yes… this link to NASA (http://climate.nasa.gov/evidence/) is a page developed to help the public better understand what the science says about this. Yes, there is evidence that the carbon is increasing in our atmosphere, that global temperatures are rising, as are sea levels. Many are experiencing some of the changes that were discussed in the 1980’s. Some areas are seeing more rain, others more drought. Gardeners in parts of the country are noticing that things they use to do in April, they now do in March. More tropical plants and animals are migrating north – there are at least three records of red and black mangroves growing the Florida panhandle and a snook was caught a couple of years ago at Dauphin Island, Alabama. These subtle changes have been noticed by some. Others, such as those in southeast Florida, have witnessed more direct evidence, such as portions of A1A going underwater during extreme high tides. But there is science to support this.

Islands in the south Pacific who are dealing with the impacts of sea level rise during storm events.

Photo: Greenpeace

What is causing sea level rise?

Well, according to a document published by Florida Sea Grant there are three general causes.

- Temperature – as the atmosphere and oceans warm the water expands thus causing the sea level to rise. This thermal expansion has accounted for about 25% of the sea level rise we have witnessed; between 1993 and 2010 it accounted for 40% of it.

- Ice melt – 60% of the current rise in sea level has been due to the melting of land based ice; such as glaciers.

- Land fall – for a variety of reasons, some coastal land masses have actually dropped; thus forcing the sea level to rise.

What do the current models predict for future sea level rise?

Most of the models are predicting an increase between 1.5 and 4.5 feet, depending on where you are, by 2100.

So what?

Again some coastal communities are experiencing impacts now. South Florida Water Management District is currently replacing all of their gravity flow drains due to the fact that sea level has risen enough that they only work at low tide. Monroe County (Florida Keys) is now replacing their vehicles at a faster rate due to constant driving through salty flood waters. Many Florida coastlines are now experiencing saltwater intrusion of their freshwater supply. This is partially due to the over consumption of that resource but it is also due to sea level rising introducing salt water to these systems. There has been increased flooding in many parts of the country, including the Florida Panhandle.

So what does this mean for our local estuaries?

As we have said, sea level rise has occurred before – will this be a problem for our estuarine habitats? Generally ecosystems adjust to environmental change over time but they cannot respond if these changes occur too fast. Scientists have determined that an increase of 0.13” of sea level/year will flood our coastal marshes and we may lose them; currently the rate is about 0.11”/year. It is believed that our barrier islands will “roll” landward but science is not sure how fast this will happen. There may be changes in species composition within our estuaries – which could be good or bad – and there is certainly room for the expansion of invasive species.

A graphic indicating the potential flooding of Florida.

Graphic: Green Policy 360

How has government responded?

Federal and county governments have responded – the state… not so much. According to Thomas Ruppert (Florida Sea Grant) the local governments have done the best job planning for these future changes. Many areas in the state now require some form of sea level rise planning in all new development projects. At the very least coastal communities should look at future development plans and think long term as to where flooding may become a bigger issue.

“The times they are a changing…”

by Rick O'Connor | Sep 21, 2015

A portion of the Aucilla River flows through a landscape of dramatic and unusual geologic formations. Join us for this tour to see an amazing sequence of sinks and river rises, created as the river alternately disappears into the underlying karst and resurfaces. Fringed with moss-draped trees and native palms, the sinks are pools of black water easily viewed by walking the surrounding embankments along a 4.5 mile-segment of the Florida National Scenic Trail.

Your guides will cover the human history of this wildlife-rich Aucilla River landscape, which extends back 12,000 years to the Pleistocene epoc when mastodons, saber-tooth tigers and other large mammals roamed a landscape that resembled the African savannahs of today. The 1983 unearthing of a 12,000-year old mastodon tusk exhibiting cut marks— evidence of slaughter by humans — provides some of the earliest known evidence of man on this continent.

When: Wednesday, September 30th 2015 ● 10:00 am – 4:00 pm EDT

Where: meet at JR’s Aucilla River Store, 23485 US 98, Lamont, FL 32336 (east of the Aucilla River bridge, the boundary between Jefferson and Taylor counties)

Bring: comfortable hiking boots/shoes, weather-appropriate clothing, hiking stick or trekking pole, water bottle, bug spray, day pack; lunch prepared by Tupelo’s Bakery in Monticello will be provided

Cost: $25.00 per adult

Register at: http://uf-extension-pol-2015-aucilla-sinks-hike.eventbrite.com

Space is limited.

Please feel free to share this announcement and attached flyer with those you know who may be interested. And we hope you can join us for this trip if you’ve never seen this beautiful, mysterious place.

Will Sheftall, for Extension Natural Resource Agents in the Panhandle

sheftall@ufl.edu

by Rick O'Connor | Sep 21, 2015

A couple of years a few agencies in south Alabama put together something they called the Alabama Birding Trail. It was a relatively simple idea really – they developed a brochure that marked different locations where visitors could enjoy birding in the two county area. They had large signs posted at those locations so that the visitor knew they were at the correct location. There seemed to be a need for this with some vacationers and they provided… It was a big success. More and more visitors were using the trail. It became so popular they that conducted a survey and found that about 40% of the visitors who come to our Gulf coast are looking for outdoor/wildlife adventures to do. Ecotourism is becoming more and more popular.

A heron exploring a local salt marsh for food.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

The panhandle is no different. Each year hundreds of thousands to millions of visitors come to our beaches. There is no doubt that we have some of the most beautiful beaches in the world, and they are a huge draw, but we have a lot of outdoor adventures to provide them as well. From scalloping in St. Joe, to snorkeling the jetties in Panama City, to fishing in Destin, to paddling in Navarre, to dolphin cruises in Pensacola the panhandle provides a wide variety of activities for both the local residents and visitors to enjoy – and employment for many.

So what does this have to do with estuaries?

Well, for most of these businesses a healthy wildlife population is needed. A dolphin cruise with no dolphin is not much. Visitors coming to stay on our beaches will certainly enjoy the white sand and emerald waters. They will return home with pictures and stories of how beautiful it was and how they hope to return – but if they saw a sea turtle that week, or went snorkeling and found thousands of tropical fish to view, or kayaked over a lagoon and found horseshoe crabs or stingrays… the stories get better and their urge to return grows. Wildlife and healthy estuaries are good for business – for everyone.

Paddling Blackwater River.

Photo: Adventures Unlimited

In 2014 the Escambia and Santa Rosa county extension offices launched a program called Naturally EscaRosa to help both locals and visitors locate both agritourism and ecotourism businesses in the two county area. The sight provides information on camping, hiking, fishing, sailing, snorkeling, biking, wildlife viewing, and farm tours (of which the popularity is growing across the country). Most of these depend on a healthy bay. Health advisories, fish kills, and loss or degradation of habitat are all problematic for the ecotourism industry. Snorkeling and finding no scallops, paddling over a lagoon and seeing no wildlife, or a slow fishing day on a charter will obviously hurt business – and remember the spin-off’s such as hotels and restaurants as well.

Estuaries have certainly benefitted this industry. From providing a nursery ground for the species we are trying to view or catch, to paddling through a peaceful salt marsh to get away from the hustle and bustle of everyday life, estuaries have been an important part of our lives. And the sunsets… don’t forget the sunsets.

Spadefish on a panhandle snorkel reef.

Photo: Navarre Beach Snorkel

We encourage all locals and visitors to get out and enjoy the beauty of our bays. As the beach season ends the crowds are down, the weather is cooler, and it is a perfect time to venture out. For information about different activities in your area contact your local tourism board, or your county extension office.

by Rick O'Connor | Sep 20, 2015

Yea, seafood… who doesn’t like seafood… actually, based on a small scale survey I conducted with marine science students over the last 28 years I have found a slight increase in the number of those who do not. Curious about this, I followed up by asking whether their concern was seafood safety or other. Almost all said they just did not like the taste. Okay… I can take that… there are something I do not like either BUT I LIKE SEAFOOD. The survey also showed that almost every year with young/old or male/female – shrimp was at the top of their favorite list. After shrimp the next 3-4 choices for males was some type of fish. For females it varied – fish, lobster, calamari, to name a few.

Shrimping depends on healthy estuaries.

Photo: NOAA

So what does this have to do with estuaries…

Well, you may not know this but 90% of the commercial important marine species require estuaries for at least part of their life cycles. Just as humans select a neighborhood to live and raise their kids based on safety and schools – “fish parents” find everything they want for their “kids” in an estuary. They are shallow – allowing light to reach much of the bottom where submerged plants, like seagrasses, can grow. These seagrasses provide hiding places and a place for small algae to attach – which is an important food source for many of them. There are other places for them to hide as well – emergent salt marshes and oyster reefs are biologically very productive habitats. Many of the developing larva and juveniles require lower salinities to begin and complete their life cycles; venturing to the open Gulf only when they have developed a tolerance for the higher salinities. The freshwater discharge not only lowers the salinity it also brings nutrients. These nutrients, along with the sunlight reaching much of the water column, produce an abundance of microscopic plankton – food for the young. The nutrients, thermal mixing, low salinities, and variety of habitats provide a combination for one of the most biologically diverse ecosystems on the planet – a great place to grow up… and much of it we enjoy eating.

Most of what we consume in the seafood world is divided into shellfish and finfish. Some of it is harvested and sold commercially, some we collect recreationally. In the shellfish world we are talking mollusk and crustaceans – two of the most popular seafood groups on the planet. The mollusk include snails, oysters, clams, mussels, scallops, and cephalopods like squid and octopus. Many of these species live in our estuaries their entire life cycle. Most are slow moving creatures – if they move at all – and have provided a living for some humans, recreation for many, for decades – though the landings of these species are on the decline… more on this in a later issue.

Oysters are one of the more popular shellfish along the panhandle.

Photo: FreshFromFlorida

Crustaceans include the ever popular gulf shrimp. We actually have three different species of bay shrimp we like – white, brown, and pink shrimp. There are other varieties found offshore we are now consuming, but these have been the big three. Blue crab – my personal favorite – is another popular crustacean. Though these are still harvested commercially, “crabbing” with your kids is a long time popular panhandle activity – and the day always ends well with a great meal. Crustaceans are more mobile and conduct small migrations during their life cycles. Shrimp develop within the estuary and then move offshore for breeding where the incoming tide brings the larva back to the estuary. Blue crabs migrate to the head of the bay for breeding and the females return to the lower end of the estuary for egg development and larva release – they may enter the Gulf during this process but tend to stick to the bays for the entire cycle.

The famous Gulf Coast shrimp.

Photo: Mississippi State University

In the finfish world we are talking drum, snapper, grouper, trout, whiting, mullet, flounder, sheepshead, and many more. These species have provided both a living for the commercial fishermen and recreation for families for years. Many species breed and grow within the estuary while others make trips in and out of the bay to complete their cycles. In addition to commercial and family recreation charter fishing has increased as a business along the Gulf coast.

One of the more popular finfish – the grouper.

Photo: Bay County Extension, UF IFAS

We hope you and your family enjoy local seafood from our bays. There are several websites and apps, such as Seafood@Your Fingertips, that can help you locate local seafood – or you can go catch some yourselves! If harvesting recreationally be reminded that there are regulations and licenses required. You can read more about those at MyFWC.com.