by Rick O'Connor | Feb 10, 2022

It is now mid-winter and much colder than our trip in January. During February’s hike the temperature was 44°F, compared to 62°F in January. It was overcast with a cold breeze from the northeast – again, colder. When conditions are like this I am not expecting to see much. If I did find something I would expect it to be one of our warm blood friends, mammals or birds, and even they would prefer a day with more sun and less breeze. But I came to see what was out roaming. So, a hike I made.

The Gulf front at Park East near Big Sabine.

This month I hiked the Big Sabine area east of Pensacola Beach. It began with a shore walk along the Gulf and then a transect across the different dune fields to the marshes and seagrasses along the Santa Rosa Sound.

There was no one out today. You could see footprints in the sand, and it had that characteristic “squeak” sound of fresh sand or snow. The only wildlife I saw on the Gulf side was a group of pelicans sitting on very calm water, obviously enjoying the morning. However, you could see footprints of mammals that had come earlier. There are raccoons, armadillos, mice, coyotes, and occasional reports of otters on Santa Rosa Island. There were a lot of skunks on the island prior to Hurricane Ivan (2004), but I have not seen any since. There have been reports of bears on the island as well. I have never seen one, nor their tracks, so do not think they are frequent visitors. I did find a dead shark tossed up on the beach by a fisherman. Not sure if they were trying to catch it or not.

A variety of mammals are found on barrier islands. Most move at night and you know they are there only by their tracks.

This small shark was found on the beach during the hike. I am not sure why they did not return it to the Gulf.

As I began my transect across the island I ventured into the secondary dune field, which during summer is extremely hot. This part of the island reminds me somewhat of a desert. Very dry, open, and at times very hot. Like the desert it comes alive more at night, but during winter you might see animal movement during the warm parts of the day. I did see mammalian tracks, which included humans and dogs.

This dune field also holds ephemeral ponds which can harbor a variety of life during the warmer months. Today I only found one blooming yellow-bladder wort as well as other carnivorous plants along the bank such as sundews and ground pines.

Yellow bladder wort is one of the small carnivorous plants that live on our barrier islands.

Sundews are another one of the small carnivorous plants found here.

From the open dune field, you venture into the tertiary dunes and the maritime forest. Trees grow here but their growth is stunted due to the salt content in the air. None the less, pine and oak hammocks liter this dune area providing great hiding places for wildlife. Though we did not see any today, I am expecting to find some as the weather warms.

The backside of the island is where you will find the salt marsh. This brackish wetland harbors its own community of creatures, which were not visible today but will be in the spring. Between the tertiary dunes and the marsh runs a section of the Florida Trail. Hikers can walk this section and observe wildlife from both ecosystems.

The larger dunes of the tertiary dune field.

Tree hammocks are common in the tertiary dune fields and provide good places for wildlife.

I eventually reached the Sound and the seagrass beds that exist there. Today, here was nothing really moving around, though I did find a dead jellyfish drifting in the waves. As the island wildlife tends to hideout the winter in burrows, the fish move to deeper water where it is warmer.

The backside of these large dunes drop quickly back to sea level.

Many plants in the tertiary dunes exhibit “wind sculpting”. It appears someone has taken a brush and “brushed” the tree towards the Sound.

Scat is another sign used to identify mammal activity in the dunes.

Portions of the Florida Trail cut through the tertiary dune field of Big Sabine.

The salt marsh

This holding pond is a remnant of an old fish hatchery from the late 1950s and is primarily freshwater.

Seagrass meadows can be found in Santa Rosa Sound and harbor a variety of marine life.

Jellyfish are common on both sides of the island. This one has washed ashore on Santa Rosa Sound.

There was little out today other than a few birds. We will see what late winter will expose next month.

by Rick O'Connor | Jan 27, 2022

Members of the family Poeciliidae are what many call “livebearers”. Live bearing meaning they do lay eggs as most fish do, but rather give birth to live young. But this is not to be confused with live-bearing you find in mammals – which is different.

Most fish lay eggs. The females and males typically have a courtship ritual that ends with the female’s eggs (roe) being laid on some substrate, or released into the water column, and the male’s sperm (milt) are released over them. Once fertilized the gelatinous covered eggs begin to develop.

Everything the developing young need to survive is provide within the egg. The embryo is suspended in a semi-gelatinous fluid called the amnion. Oxygen and carbon dioxide gas exchange occurs through this amnion and through the gelatinous covering of the egg itself. Food is provided in the form of yolk, which is found in a sac attached to the embryo. There is a second sac, the allantois, where waste is deposited. When the yolk is low and the allantois full – it is time to hatch. This usually occurs in just a few days and often the baby fish (fry) are born with the yolk sac still attached. Parental care is rare, they are usually on their own.

With “livebearers” in the family Poecillidae it is different.

The males have a modified anal fin called a gonopodium. They fertilize the roe not externally but rather internally – more like mammals. The fertilized eggs develop the same as those of other fish. There is a yolk sac and allantois, and the embryo is covered in amnion within the gelatinous egg covering. But these eggs are held WITHIN the female, not laid on the substrate or released into the water column. When they hatch the live fry swim from the mother into the bright new world – hence the term “livebearer”.

There are advantages to this method. The eggs are protected inside the mother, and she obviously provides parental care to her offspring. However, this does make her much slower and an easier target for predators. There is some give and take.

This differs from the “live-bearing” of most mammals in that there is still an egg. Mammals do still have a yolk sac but feeding and removing waste is done THROUGH THE MOTHER. Meaning the embryo is attached to the mother via an umbilical cord where the mother provides food and removes waste trough her placenta. There is no classic egg in this case. I say most mammals because there are two who live in Australia that still do lay eggs – the platypus and the spiny anteater, and the marsupials (kangaroos and opossums) are a little different as well – but marsupials do no lay eggs.

Biologists have terms for these. Oviparous are vertebrates that lay eggs – such as fish, frogs, turtles, and birds. Ovoviviparous are vertebrates that produce eggs but keep them within the mother where they hatch – such as some sharks, some snakes, and the live bearing fish we are talking about here. Then there are the viviparous vertebrates that do not have an egg but rather the embryo is attached, and fed by, the mother herself – like most mammals.

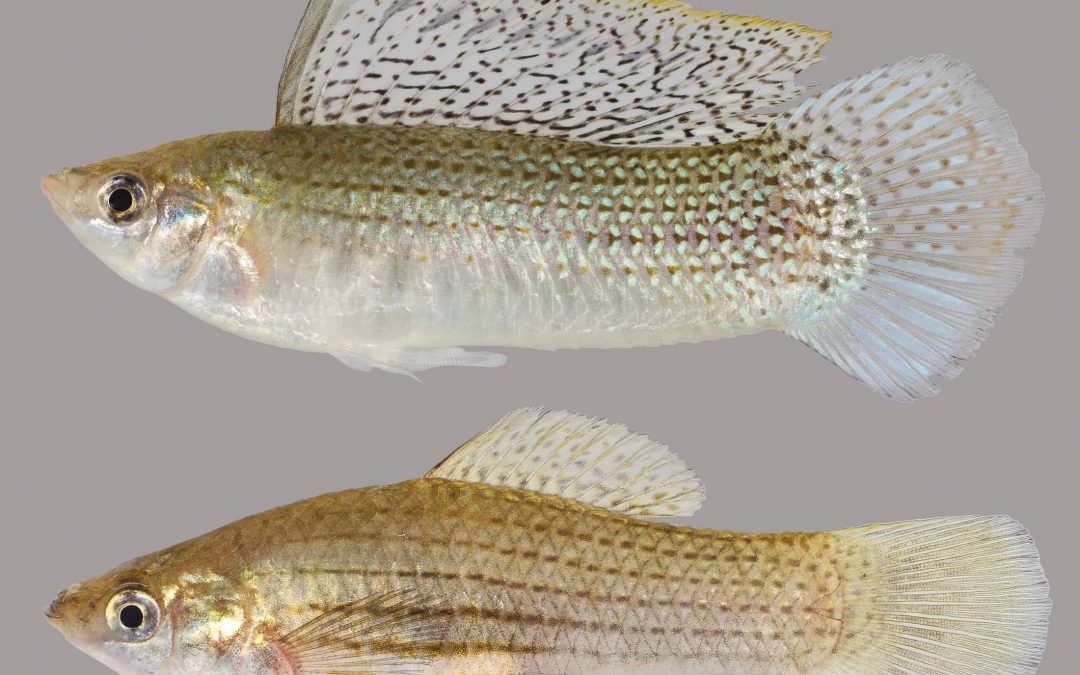

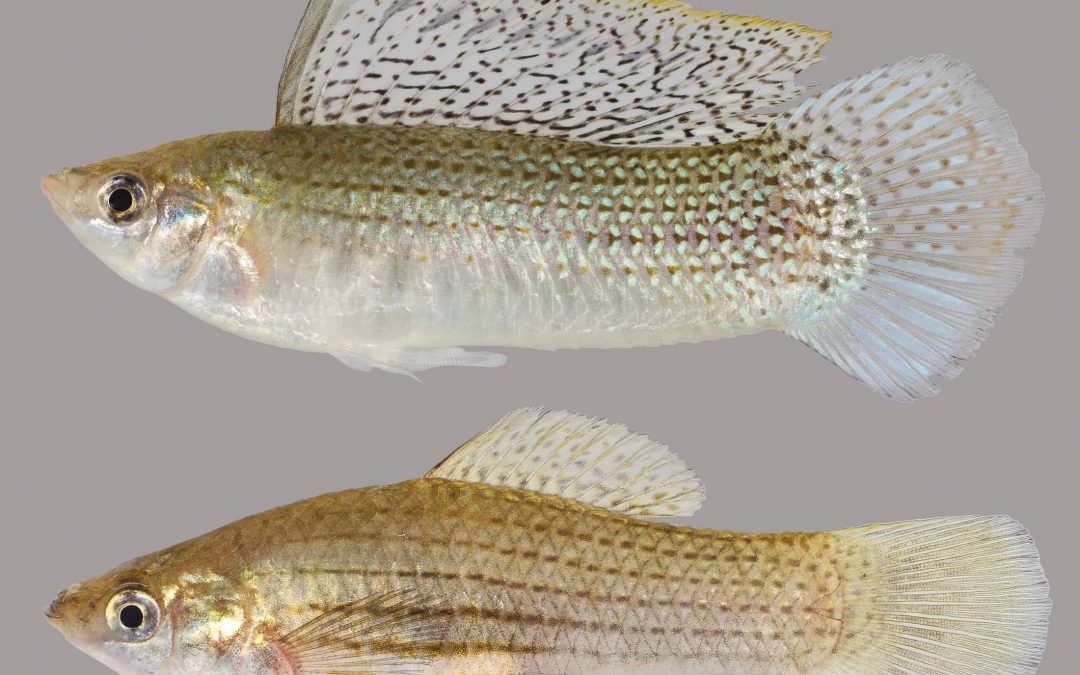

Sailfin Molly. The male is the fish above with the large “sailfin”. Note the gonopodium on his ventral side.

Photo: University of Florida

The livebearers of the family Poeciliidae are ovoviviparous. They are primarily small freshwater fish that are very popular in the aquarium trade. But there are two species that can tolerate saltwater and enter the estuaries of the northern Gulf of Mexico: the sailfin molly and the mosquitofish.

The Sailfin Molly (Poecilia latipinna) is the same fish sold in aquarium stores as the black molly. The black phase is quite common in freshwater habitats, but in the estuarine marshes the fish is more of a gray color with lateral stripes that is made up of a series of dots. They are short-stout bodied fish and the males possess the large sail-like dorsal fin from which the species gets its common name. The females resemble the males albeit no large sailfin and most found are usually round and full of developing eggs. They are very common in local salt marshes and often found in isolated pools within these habitats. The biogeographic range of this species is restricted to the southern United States, reported from South Carolina throughout the Gulf of Mexico. One would guess temperature may be a barrier to their dispersal further north along the Atlantic seaboard.

The mosquitofish.

Photo: University of Florida

The Mosquitofish (Gambusia affinis) is familiar to many people whether they know it or not. Those who know the fish know they are famous for the habit of consuming mosquito larva and some, including our county mosquito control unit, use them to control these unwanted flying insects. For those who may they are not familiar with it, this is the fish frequently seen in roadside ditches, ephemeral ponds that show up after rainstorms, retention ponds, and other scattered bodies of freshwater within the community. Most who see them call them “minnows”. There is always the question as to “where did they come from?” You have a vacant lot – it rains one day – these small fish show up – where did they come from? The same can be said for community retention ponds. The county comes in a digs a hole – it rains one day, and the retention pond fills – and there are fish in it. One explanation to their source is the movement of fish by wading birds, where the fish incidentally become attached to their feet. Again, they are often released intentionally to help control local mosquito populations. This fish is found in our coastal estuaries but does not seem to like saltwater as well as the sailfin molly. It is found in cooler water ranging throughout the Gulf and as far north as New Jersey.

Both of these fish make excellent aquarium pets, and the sailfin molly in particular can be beautiful to watch.

Reference

Hoese, H.D., Moore, R.H. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M Press, College Station TX. Pp. 327.

by Andrea Albertin | Jan 20, 2022

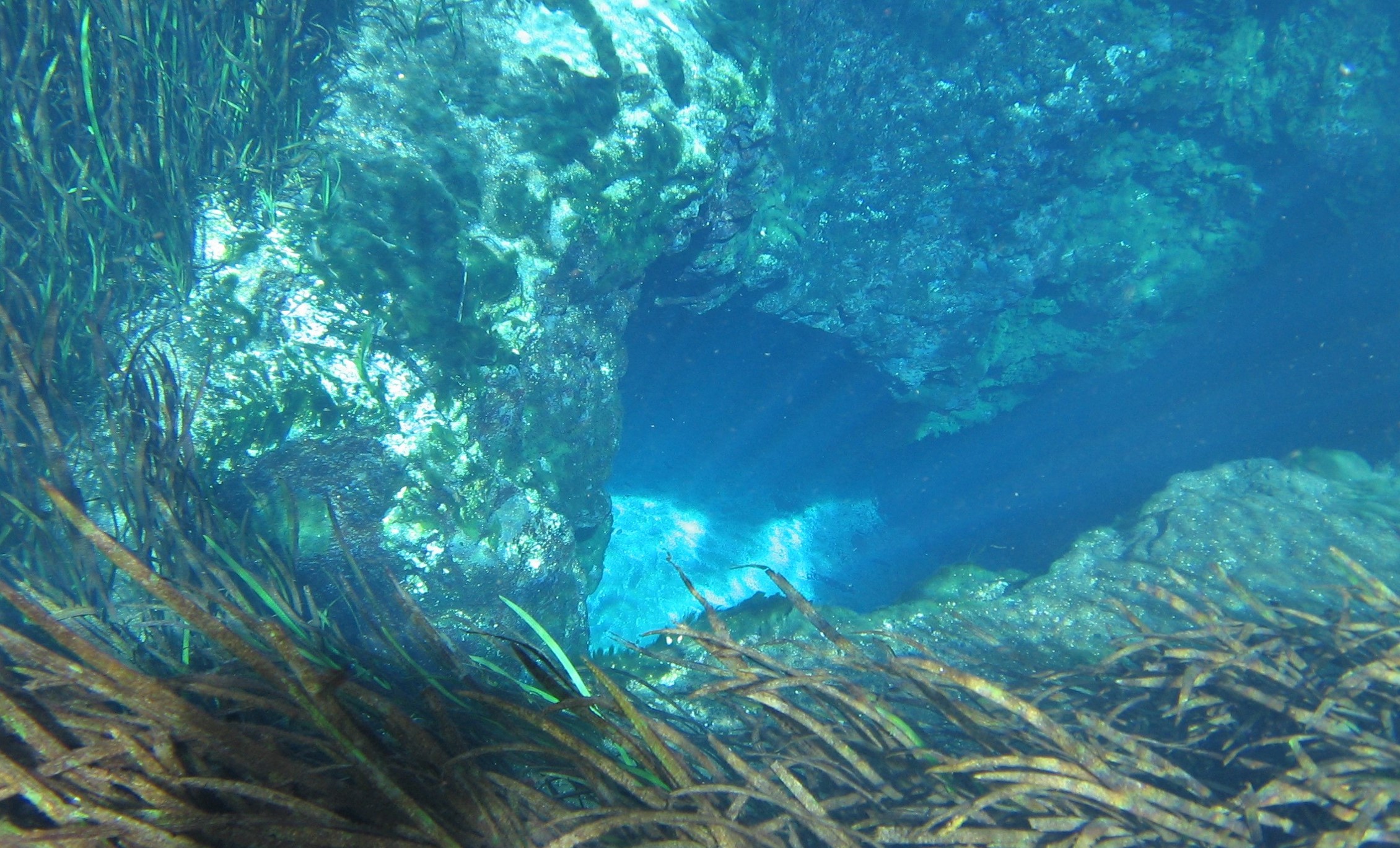

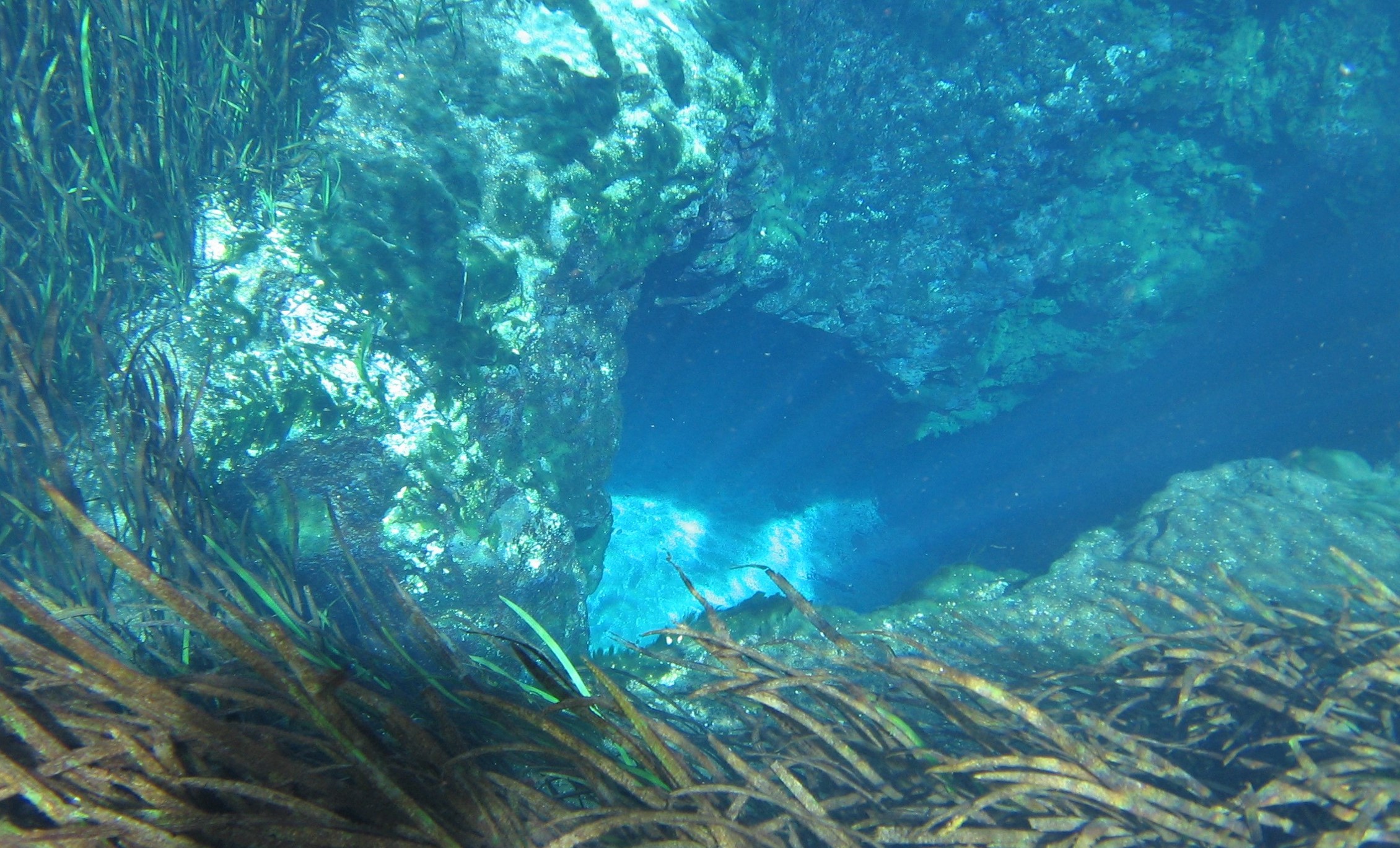

Jackson Blue Springs discharging from the Floridan Aquifer. Jackson County, FL. Image: Doug Mayo, UF/IFAS Extension.

Florida has one of the largest concentrations of freshwater springs in the world. More than 1000 have been identified statewide, and here in the Florida Panhandle, more than 250 have been found. Not only are they an important source of potable water, springs have enormous recreational and cultural value in our state. There is nothing like taking a cool swim in the crystal-clear waters of these unique, beautiful systems.

How do springs form?

We have so many springs in Florida because of the state’s geology. Florida is underlain by thick layers of limestone (calcium carbonate) and dolomite (calcium magnesium carbonate) that are easily dissolved by rainwater that percolates into the ground. Rainwater is naturally slightly acidic (with a pH of about 5 to 5.6), and as it moves through the limestone and dolomite, it dissolves the rock and forms fissures, conduits, and caves that can store water. In areas where the limestone is close to the surface, sinkholes and springs are common. Springs form when groundwater that is under pressure flows out through natural openings in the ground. Most of our springs are found in North and North-Central Florida, where the limestone and dolomite are found closest to the surface.

Springs are windows to the Floridan Aquifer, which supplies most of Florida’s drinking water. Image: Ichetucknee Blue Hole, A. Albertin.

These thick layers of limestone and dolomite that are below us, with pores, fissures, conduits, and caves that store water, make up the Floridan Aquifer. The Floridan Aquifer includes all of Florida and parts of Georgia, South Carolina, and Alabama. The thickness of the aquifer varies widely, ranging from 250 ft. thick in parts of Georgia, to about 3,000 ft. thick in South Florida. The Floridan is one of the most productive aquifer systems in the world. It provides drinking water to about 11 million Floridians and is recharged by rainfall.

How are springs classified?

Springs are commonly classified by their discharge or flow rate, which is measured in cubic feet or cubic meters per second. First magnitude springs have a flow rate of 100 cubic feet or more per second, 2nd magnitude springs have a rate of 10-100 ft.3/sec., 3rd magnitude flows are 1-10 ft.3/sec. and so on. We have 33 first magnitude springs in the state, and the majority of these are found in state parks. These springs pump out massive amounts of water. A flow rate of 100 ft.3/sec. translates to 65 million gallons per day. Larger springs in Florida supply the base flow for many streams and rivers.

What affects spring flow?

Multiple factors can affect the amount of water that flows from springs. These include the amount of rainfall, size of caverns and conduits that the water is flowing through, water pressure in the aquifer, and the size of the spring’s recharge basin. A recharge basin is the land area that contributes water to the spring – surface water and rainwater that falls on this area can seep into the ground and end up as part of the spring’s discharge. Drought and activities such as groundwater withdrawals through pumping can reduce flow from springs systems.

If you haven’t experienced the beauty of a Florida Spring, there is really nothing quite like it. Here in the panhandle, springs such as Wakulla, Jackson Blue, Pitt, Williford, Morrison, Ponce de Leon, Vortex, and Cypress Springs are some of the areas that offer wonderful recreational opportunities. The Florida Department of Environmental Protection has a ‘springs finder’ web page with an interactive map that can help you locate these and many other springs throughout the state.

https://nwdistrict.ifas.ufl.edu/nat/2020/04/09/the-incredible-floridan-aquifer/

by Chris Verlinde | Nov 19, 2021

Photo: Chris Verlinde

Photo: Chris Verlinde

The diversity and natural beauty of the Escribano Point Wildlife Management area is breathtaking. These six square miles of conservation lands provides many types of outdoor recreation including: birdwatching, kayaking, camping, swimming, fishing and hiking. The bays, estuaries, river swamps and other coastal habitats are managed to preserve native plants and animals. Visit Escribano Point Wildlife Management Area (WMA) soon and discover this piece of old Florida.

The Escribano Point WMA is part of state-owned conservation lands that provide habitat for rare plants and animals and promote water quality in Blackwater Bay, East Bay and the Yellow River. The diverse habitats found in Escribano Point WMA provide home to many types of wildlife including, deer, turkey, Florida Black Bears, birds, reptiles amphibians and fish.

As part of the Florida Master Naturalist Program’s 20th Anniversary, a small but mighty group hit the water just as the air temperature broke 60 degrees on Saturday. We kayaked up Fundy Bayou and out to Fundy Cove located along the southeast side of Blackwater Bay in Santa Rosa County, Fl.

As part of the Florida Master Naturalist Program’s 20th Anniversary, a small but mighty group hit the water just as the air temperature broke 60 degrees on Saturday. We kayaked up Fundy Bayou and out to Fundy Cove located along the southeast side of Blackwater Bay in Santa Rosa County, Fl.

We traveled through freshwater and saltwater marshes, along scrubby flat woods, beach and mesic hammock habitats. Ospreys, a kingfisher, and red-headed woodpecker entertained the group. The air temperature warmed as we paddled. When we arrived at the junction of Fundy Creek and Blackwater Bay, Blackwater Bay was rough. We paddled to the campground for lunch and enjoyed the peaceful beauty around us.

Thanks to Kayak Dave, one member of the group checked an action on her bucket list to paddle again.

Escribano Point WMA is a treasure located in Santa Rosa County, FL., approximately 20 south of Milton, FL . Take some and visit for a day or two, there are 2 campgrounds located at this WMA. Enjoy!

by Evan Anderson | Nov 19, 2021

There are many problems that can plague a plant in our environment, from fungi that love the humidity in North Florida to insects that chew through leaves. One less common but interesting source of stress for plants comes from…other plants?

Most plants are content to gather energy from sunlight and nutrients from the soil in which they sink their roots. Some species, however, have taken up thievery as a lifestyle. Parasitic plants are those that take the nutrients they need to grow from other plants. Some rely completely on their hosts for nutrients, others are able to produce at least some of their own, while yet more can live on their own but steal nutrients if another plant is conveniently nearby. Furthermore, there are some plants and similar organisms that may seem to be parasitic, but actually do no harm.

Mistletoe is a common sight especially in the winter when trees’ leaves have dropped. It relies on its host for water and nutrients, though it can produce energy from photosynthesis. Being evergreen has led it its adoption as a symbol Christmastime, and it has historically been important to other cultures such as the Celtic druids. Too much mistletoe can weaken a tree, and removing it can help to reinvigorate one that is struggling. Physical pruning is often the only method available for its removal, and this can be difficult on a tree of any size.

Yellow tendrils and white flowers of dodder.

Dodder has a strange appearance, looking like someone threw a batch of angel-hair pasta all over a plant. There are ten different species of dodder in Florida and they may be found on a variety of host plants. This parasite is leafless, takes all it needs from its host, and cannot survive independently. Though it germinates from the ground, it has no true roots. Controlling an infestation of dodder involves removing affected plants or at least pruning off the branches that are hosting the parasite. Herbicides will kill it, but they will also kill the host.

Ghost Pipe flowers

Ghost Pipe may be seen flowering from early summer through autumn, typically in woodland areas. It does not take its nutrients directly from a tree, but instead from mycorrhizal fungi. These helpful fungi attach to a tree and act like extra roots, assisting to absorb nutrients in return for energy from the plant. The ghost pipe helps itself to both nutrients and energy and does not bother to photosynthesize for itself, which gives it its stark white appearance.

Lichen may grow profusely on trees, but does not harm the plant.

There are also plenty of harmless plants out there, such as Spanish moss and resurrection fern, which grow on trees but are not parasitic. Lichens, while not plants, are similarly prolific on the bark of trees, but do no harm.

For help in identifying a potential parasitic plant, contact your local Extension office.

by Rick O'Connor | Oct 21, 2021

Catfish…

There are a lot of fish found along the Florida panhandle that many are not aware of, but catfish are not one of them. Whether a saltwater angler who captures one of those slimy hardhead catfish to a lover of freshwater fried catfish – this is a creature most have encountered and are well aware of.

Growing up fishing along the Gulf of Mexico, the “catfish” was one of our nemesis. Slinging your cut-bait out on a line, if you were fishing near the bottom, you were likely to catch one of these. Reeling in a slimy barb-invested creature, they would swallow your bait well beyond the lip of their mouths and it would begin a long ordeal on how to de-hooked this bottom feeder that was too greasy to eat. Many surf fishermen would toss their bodies up on the beach with the idea that removing it would somehow reduce their population. Obviously, that plan did not work but ghost crabs will drag their carcasses over to their burrows where they would consume them and leave the head skull that gives this species of catfish it’s common name “hardhead” catfish, or “steelhead” catfish. This hard skull has bones whose shape remind you of Jesus being crucified and was sold in novelty stores as the “crucifix fish”.

The bones in the skull of the hardhead catfish resemble the crucifixion of Christ and are sold as “crucifix fish”.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

When I attended college in southeast Alabama a group of friends wanted to go out for fried catfish. I, knowing the above about saltwater catfish, replied “why?… no…, you don’t eat catfish”. They assured me you did and so off we went to a local restaurant who sold them. Fried catfish quickly became one of my favorites. A fried catfish sandwich with slaw and beans is something I always look forward to. At that time, I was not aware of the freshwater catfish, nor the catfish farms that produce much of the fish for my sandwiches. I now have also become aware of the method of catching freshwater catfish called “noodling” – which is not something I plan to take up.

Worldwide, there are 36 families and about 3000 species of what are called catfish1. Most are bottom feeders with flatten heads to burrow through the substrate gulping their prey instead of biting it. Most possess “whiskers” – called barbels, which are appendages that can detect chemicals in the environment (smell or taste) helping them to detect prey that is buried or hard to find in murky waters. These barbels resemble whiskers and give them their common name “catfish”.

The serrated spines and large barbels of the sea catfish. Image: Louisiana Sea Grant

They lack scales, giving them the slimy feel when removing them from your hook, and also have a reduced swim bladder causing them to sink in the water – thus they spend much of their time on the bottom. The mucous of their skin helps in absorbing dissolved oxygen through the skin allowing them to live in water where dissolved oxygen may be too low for other types of fish1.

They are also famous for their serrated spines. Usually found on the dorsal and pectoral fins, these spines can be quite painful if stepped on, or handled incorrectly. Some species can produce a venom introduced when these spines penetrate a potential predator which have put some folks in the hospital1.

The size range of catfish is large; from about five inches to almost six feet. In North America, the largest captured was a blue catfish (Ictalurus furcatus) at 130 pounds. The largest flathead catfish (Pylodictis olivaris) was 123 pounds. But the monster of this group is the Mekong catfish of southeast Asia weighing in at over 600 pounds.

The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission lists six species of catfish in the Florida panhandle area. However, they are focusing on species that people like to catch2.

The Blue Catfish

Photo: University of Florida

This large blue catfish is being weighed by FWC researchers. Photo: Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

The Channel Catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) is found throughout Florida and also in many river systems of the eastern United States. It has found few barriers dispersing through these river systems. They are not typically bottom feeders having a more carnivorous diet.

The Flathead Catfish (Pylodictis olivaris) are relatively new to Florida and are currently reported in the Escambia and Apalachicola rivers. They prefer these slow-moving alluvial rivers.

The Blue Catfish (Ictalurus furcatus) were first reported in the Escambia and Yellow Rivers, there are now records of them in the Apalachicola. These catfish prefer faster moving rivers with sand/gravel bottoms and seem to concentrate towards the lower ends of major tributaries.

The White Catfish (Amerius catus) is found in rivers and streams statewide, and even in some brackish systems.

The Yellow Bullhead (Amerius natalis) are most often found in slow moving heavily vegetated systems like ponds, lakes, and reservoirs. It is reported to be more tolerant of poor water conditions.

The Brown Bullhead (Amerius nebulosus) live in similar conditions to the Yellow Bullhead.

The dispersal of freshwater catfish is interesting. How do they get from the Escambia to the Apalachicola Rivers without swimming into the Gulf and up new rivers? The answer most probably comes from small tributaries further upstream that can, eventually, connect them to a new river system. Scientists know that eggs deposited on the bottom can be moved by birds who feed in each of the systems carrying the eggs with them as they do. And you cannot rule out movement by humans, whether intentionally or accidentally.

On the saltwater side of things, there are two species – though the blue catfish has been reported in the upper portions of some estuaries in low salinities in the western Gulf of Mexico. The marine species are the hardhead catfish (Arius felis), sometimes known as the “steelhead” or the “sea catfish” – and the gafftop (Bagre marinus), also known as the gafftopsail catfish3.

The hardhead catfish is very familiar with anglers along the Gulf coast. This is the one I was referring to at the beginning of this article. It is considered inedible and a nuisance by most. They are common in estuaries and the shallow portions of the open sea from Massachusetts to Mexico. They are reported to have an average length of two feet, though most I have captured are smaller. Like many catfish, they possess serrated spines on their dorsal and pectoral fins. Their distribution seems to be limited by salinity.

The gafftop is also reported to have a mean length of two feet, and most that I have captured are closer to that. At one point in time, we were longlining for juvenile sharks in Pensacola Bay and caught numerous of these thinking they were small bull sharks as we pulled the lines in, until we saw the long barbels extending from them. I remember this being a very slimy fish, covered with mucous, and not fun to take off the hooks. It is reported to have good food value, though I have not eaten one. They differ from the hardheads mainly in their extended rays from the dorsal and pectoral fins. The habitat and range are similar to hardheads, though they have been reported as far south as Panama.

The extended rays of the gafftop catfish.

Photo: University of Florida.

The diversity of freshwater catfish in the U.S. goes beyond what has been reported here. This group has been found on most continents and have been very successful. There are plenty of local catfish farms where you can try your luck, have them cleaned, and enjoy a good meal.

References

1 Catfish. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Catfish.

2 Catfish. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. https://myfwc.com/fishing/freshwater/sites-forecasts/catfish/.

3 Hoese, H.D., R.H. Moore. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M Press. College Station TX. Pp. 327.