by Carrie Stevenson | Jul 2, 2020

The bright yellow perennial peanut flower is not only pretty, but edible! Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

It’s bright yellow, makes its own fertilizer, and tastes like peanut butter. On my morning walks around the track at our office, I have noticed lately that the perennial peanut (Arachis glabrata) is growing lushly, fulfilling its role as a low maintenance groundcover. The plant thrives in hot weather, full sun, and humidity, so we have nearly reached peak growing conditions for this South American native.

Perennial peanut was brought in from Brazil almost 90 years ago as a valuable hay crop and livestock forage. It is still used regularly for these purposes. However, as years of experience have borne out, there are no insect, disease, or unwanted invasive issues with the plant. The lush green groundcover has been used in the past few decades as a popular turfgrass alternative. It is drought and salt tolerant, and can thrive in low-nutrient, sandy soils.

Perennial peanut is a drought-resistant, salt-tolerant, erosion-managing groundcover. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Its bright yellow blossoms are delicate and almost orchid-like in shape, standing upright on a thin stem. As mentioned earlier, the flower is also edible and has a very light peanut flavor. The foliage, a deep green with compound leaves, lies close to the ground. Its spreading rhizomes serve as an excellent erosion control method, holding even easily washed out sandy soils in place.

Like its more well-known cousin, the perennial peanut is a legume, which means it can “fix” atmospheric nitrogen, transforming it into a form the plant can use. For a homeowner, this means you do not need to add nitrogen fertilizer. If phosphorus levels are naturally high enough in the soil (as is often the case in south Florida), only small amounts potassium-magnesium sulfate may be needed.

Perennial peanut is a great choice in open areas. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Perennial peanut is best utilized in open spaces without high foot traffic. If you’d like to see it, come out to the Escambia Extension office; there’s a large swath of it between our main building and the demonstration garden near the walking path. If you are interested in planting or maintaining it, check out these documents from UF IFAS Extension or watch this informative video from a colleague!

by Sheila Dunning | Dec 13, 2019

As the migratory birds stop off or stay in the Panhandle this winter, they need to find food, food and more food. There is a wide variety of migration activity in Florida beginning in the fall months of September, October, and November. From woodland song birds to waterfowl to the annual warbler invasion, so many different species show up in Florida. While year-to-year migration patterns and winter foraging grounds can shift for some species due to a variety of reasons, some birds stay in Florida for the winter months of December, January, and February. Some may arrive early and others may stay late.

As the migratory birds stop off or stay in the Panhandle this winter, they need to find food, food and more food. There is a wide variety of migration activity in Florida beginning in the fall months of September, October, and November. From woodland song birds to waterfowl to the annual warbler invasion, so many different species show up in Florida. While year-to-year migration patterns and winter foraging grounds can shift for some species due to a variety of reasons, some birds stay in Florida for the winter months of December, January, and February. Some may arrive early and others may stay late.

Some North American breeding birds endure harsh winters; however, they are physically suited for cold environments in a number of ways. One, they are able to drop their metabolic rate to a near comatose state using very little energy. Two, they are able to position their feathers, or puff up, to trap heat generated by their own body. Others need to head to warmer climates.

Birds migrate for two reasons. Food and weather avoidance. North American breeding birds who nest in the northern part of the continent will migrate south for the winter. As winter approaches, insect and plant life diminishes in the snow-covered states. Migrating birds head south in search of food. Places like Florida are rich in insects, plant life, and nesting grounds.

Birds need high energy food to stay warm. Berry and seed producing plants contain proteins, sugars and lots of fats. Many native trees, shrubs and grasses can aid migratory and winter visiting birds in their relentless search for food. Gardening for birds and other wildlife enables an opportunity for people to experience animals up close, which providing an important habitat in the urban environment.

For more information on which plants are preferred by specific bird species go to: https://www.audubon.org/native-plants

For more information on landscaping for wildlife refer to: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/UW/UW17500.pdf

by Sheila Dunning | Oct 10, 2019

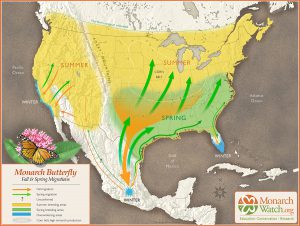

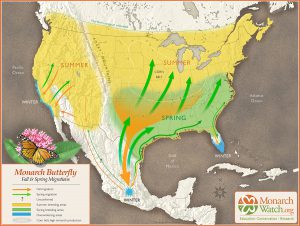

Over 1.8 million Monarch butterflies have been tagged and tracked over the past 27 years. This October these iconic beauties will flutter through the Florida Panhandle on their way to the Oyamel fir forests on 12 mountaintops in central Mexico. Monarch Watch volunteers and citizen scientists will be waiting to record, tag and release the butterflies in hopes of learning more about their migration and what the 2019 population count will be.

Over 1.8 million Monarch butterflies have been tagged and tracked over the past 27 years. This October these iconic beauties will flutter through the Florida Panhandle on their way to the Oyamel fir forests on 12 mountaintops in central Mexico. Monarch Watch volunteers and citizen scientists will be waiting to record, tag and release the butterflies in hopes of learning more about their migration and what the 2019 population count will be.

This spring, scientists from World Wildlife Fund Mexico estimated the population size of the overwintering Monarchs to be 6.05 hectacres of trees covered in orange. As the weather warmed, the butterflies headed north towards Canada (about three weeks early). It’s an impressive 2,000 mile adventure for an animal weighing less than 1 gram. Those butterflies west of the Rocky Mountains headed up California; while the eastern insects traveled over the “corn belt” and into New England. When August brought cooler days, all the Monarchs headed back south.

What the 2018 Monarch Watch data revealed was alarming. The returning eastern Monarch butterfly population had increased by 144 percent, the highest count since 2006. But, the count still represented a decline of  90% from historic levels of the 1990’s. Additionally, the western population plummeted to a record low of 30,000, down from 1.2 million two decades ago. With estimated populations around 42 million, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service began the process of deciding whether to list the Monarch butterfly as endangered or threatened in 2014. With the additional information, FWS set a deadline of June 2019 to decide whether to pursue the listing.

90% from historic levels of the 1990’s. Additionally, the western population plummeted to a record low of 30,000, down from 1.2 million two decades ago. With estimated populations around 42 million, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service began the process of deciding whether to list the Monarch butterfly as endangered or threatened in 2014. With the additional information, FWS set a deadline of June 2019 to decide whether to pursue the listing.

Scientists estimate that 6 hectacres is the threshold to be out of the immediate danger of migratory collapse. To put things in scale: A single winter storm in January 2002 killed an estimated 500 million Monarchs in their Mexico home. However, with recent changes on the status of the Endangered Species Act, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has delayed its decision until December 2020. One more year of data may be helpful to monarch conservation efforts.

Individuals can help with the monitoring and restoring the Monarch butterflies habitat. There are two scheduled tagging events in Panhandle, possibly more. St. Mark’s National Wildlife Refuge is holding their Butterfly Festival on Saturday, October 26 from 10a.m. to 4 p.m. Henderson Beach State Park in Destin will have 200 butterflies to tag and release on Saturday, November from 9 – 11 a.m. Ask around in the local area. There may be more opportunities.

Individuals can help with the monitoring and restoring the Monarch butterflies habitat. There are two scheduled tagging events in Panhandle, possibly more. St. Mark’s National Wildlife Refuge is holding their Butterfly Festival on Saturday, October 26 from 10a.m. to 4 p.m. Henderson Beach State Park in Destin will have 200 butterflies to tag and release on Saturday, November from 9 – 11 a.m. Ask around in the local area. There may be more opportunities.

There is something more you can do to increase the success of the butterflies along their migratory path – plant more Milkweed (Asclepias spp.). It’s the only plant the Monarch caterpillar will eat. When they leave their hibernation in Mexico around February or March, the adults must find Milkweed all along the path to Canada in order to lay their eggs. Butterflies only live two to six weeks. They must mate and lay eggs along the way in order for the population to continue its flight. Each generation must have Milkweed about every 700 miles. Check with the local nurseries for plants. Though orange is the most common native species, Milkweed comes in many colors and leaf shapes.

by hollyober | Oct 10, 2019

Insect pests can destroy substantial quantities of crops, prompting growers to invest heavily in pesticide use. Previ

These three common species of bats in FL, GA, and AL eat insect pests notorious for causing substantial damage to crops: the Seminole bat (Lasiurus seminolus), southeastern bat (Myotis austroriparius), and evening bat (Nycticeius humeralis) (photo credits @MerlinTuttle.org).

ous research in Texas suggested that bats could reduce pesticide costs by over a million dollars within their state, due to the bats’ fondness for pests that damage cotton. Scientists at UF/IFAS recently collected evidence locally that indicates bats are providing valuable assistance with pest reduction for many of the crops grown here too.

During spring and summer of 2018 scientists at UF clarified what the common species of bats were eating in north Florida, south Georgia, and south Alabama. We investigated 161 bats across 21 counties and found that 28% of these bats ate at least one Lepidopteran (moth) pest species, 21% ate a Coleopteran (beetle) pest, and 18% ate a Hemipteran (true bug) pest. In total, 12 different species of agricultural pest species were eaten by these bats.

The moth pests consumed by bats were:

- Green Cutworm Moth (Anicla infecta)

- Tobacco Budworm (Chloridea virescens)

- Soybean Looper (Chrysodeixis includens)

- Garden Tortrix (Clepsis peritana)

- Lesser Cornstalk Borer (Elasmopalpus lignosellus)

- Corn Earworm (Helicoverpa zea)

- Beet Armyworm (Spodoptera exigua)

- Fall Armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda)

- Red-Necked Peanutworm Moth (Stegasta bosqueella)

The beetle and true bug pests consumed by bats were:

- Hairy Fungus Beetle (Typhaea stercorea)

- Tarnished Plant Bug (Lygus lineolaris)

- Two-lined Spittlebug (Prosapia bicincta)

Three of these pests (Soybean Looper, Beet Armyworm, and Two-lined Spittlebug) were most often consumed by pregnant and juvenile bats. This is good news for growers of crops affected by these pests because you have a sound option for increasing the likelihood of bats helping control them. The trick is to provide the conditions that adult female bats like near the crops these pests feed on (e.g., soybeans, peanut, cotton, corn, sorghum, safflower). Most female bats pick a maternity roost in early spring. A maternity roost is a structure that provides warm, dry, dark conditions for female bats to sleep in during the day, and it is ultimately where they give birth to pups. When selecting a site to set up a maternity roost, female bats look for structures that are large enough to provide shelter for a large number of bats. A roomy structure can accommodate many bats, which allows the flightless pups to keep each other warm while the mothers fly in search of food at night. Installing a bat house like those shown here can provide conditions appropriate for a maternity colony, increasing your chances of having bats help control these insect pests.

Another useful strategy for enhancing pest control services by bats involves creating or maintaining structures that could serve as natural roost sites for bats. The natural structures bats prefer include large trees with cavities, dead and dying trees with peeling bark, oak trees with Spanish moss, and palm trees allowed to maintain their dead fronds. In agricultural areas and suburban areas these types of trees are often in short supply.

Maintaining large, old trees of a mix of species, and supplementing with bat houses, can help ensure there are plenty of roosting options for bats. This, in turn, will increase the likelihood that bats are available to assist with your pest management.

by Molly Jameson | Apr 18, 2019

With spring upon us, the mighty monarch butterflies have begun their long trek to the north from Mexico, looking to time their migration with growth of the milkweed plants in the southeastern United States. Mated monarch females lay hundreds of eggs along their journey, but only two percent of these eggs will survive to become mature caterpillars to carry on the next generation.

The monarch butterfly.

Photo: Steven Katovich USDA Forest Service

Monarch larvae rely exclusively on milkweed for nutrients, so it is of upmost importance that the plants are available to the offspring at the correct time. If the adult monarchs arrive too early, the milkweeds may not have had enough time to grow after late frosts. If they arrive too late, the milkweed vegetation may not support the nutrient needs of the caterpillars. In addition, the milkweeds contain a poisonous toxin, cardiac glycoside, that stays within the caterpillars’ bodies once consumed. This does not harm the larvae, but actually helps them, as it makes the young and adult butterflies taste terrible and makes them poisonous to potential predators.

For these reasons, it is important that we all do our part to support the growth of native milkweed species. Locally, the Monarch Milkweed Initiate at the St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge educates the public about milkweed and monarchs and grows and transplants native milkweed to support the monarchs on their migration.

When planting milkweed, be aware that there is a popular commercialized non-native tropical milkweed species that is not appropriate for the monarchs in our area. This species, Asclepias curassavica, can flower year-round, luring the monarchs to stay and breed in the winter when they should be on their way back to Mexico to escape freezing temperatures. Staying and breeding too long can make the monarchs susceptible to a protozoan parasite, Ophryocystis elektroscirrha (OE for short), that infects the caterpillars when feeding, reducing their lifespan, body mass, mating success rate, and ability to migrate.

Butterfly milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa)

Photo: John Ruter, University of Georgia

Swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata).

Photo: David Cappaert

Luckily, there are about 21 native milkweed species in Florida. Many native milkweeds in the Florida Panhandle require specialized care when grown for transplanting, as different species have adapted to a range of habitats. The Asclepias tuberosa, commonly referred to as butterflyweed, is considered easiest to grow as they transplant well and thrive in full sun. Others, such as Asclepias perennis, or aquatic milkweed, and Asclepias incarnata, swamp milkweed, must be grown using trays without drain holes, as their “feet” must be kept wet. The Asclepias humistrata, or sandhill milkweed, requires a drier, heavier soil.

Monarch catepillar (Danaus plexippus).

Photo: Steven Katovich, USDA Forest Service

To support the monarchs and grow milkweed in your garden, come to the Leon County Extension Office at 615 Paul Russell Road on Saturday, May 11, from 9:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. for the Spring Open House and Plant Sale. Master Gardeners have been busy growing native milkweeds for this event and will be on hand selling the transplants. There will also be many other Florida Friendly and native plants available, along with guided garden tours, kids’ activities, the UF/IFAS Bookstore, a silent auction, live music by the Tallahassee Woodwind Quintet, refreshments, and Master Gardeners and Extension Agents on-hand to answer any of your gardening questions.

by Sheila Dunning | Apr 18, 2019

Young Longleaf Pine

All of Florida’s ecosystems contain pine trees. There are seven native species in the state; Sand, Slash, Spruce, Shortleaf, Loblolly, Longleaf, and Pond. Each species grows best in its particular environment. Pines are highly important to wildlife habitats as food and shelter. Several species are equally valuable to Florida’s economy. Slash, Loblolly, and Longleaf are cultivated and managed to provide useful products such as paper, industrial chemicals, and lumber. All pines are evergreens, meaning they keep foliage year-round. The leaves emerge from the axil of each scale leaf into long slender needles clustered together in bundles. Needles are produced at the growing tips of each branch and remain on the tree for several years before turning reddish-brown and falling off. The bundles are referred to as “fascicles”. The length and number of needles in each fascicle is one way to help identify the different pine species.

A handy rule of thumb is that pines starting with “S” have needles in twos, while pines starting with “L” have needles in threes. And slash pine, which starts with “SL” has needles in twos and threes. The pond pine is also a three-needled fascicle. Pay attention to their length and the number that are held in a fascicle. Because the numbers per fascicle may vary, be sure to check several fascicles to get an overall sense for the plant! Longleaf has the longest needle, measuring over 10 inches. While sand pine has the shortest needles at around 2 inches in length. Pine cones are also a means for identification. Typically the longer the needle, the bigger the cone. But, they also vary in attachment and “spinyness’.

Cone of Loblolly Pine, attached directly to the stem

The outer (dorsal) surface of each seed cone scale has a diamond-shaped bulge, or “umbo,” formed by the first year’s growth. The umbo may or may not be armored with a “prickle,” a sharp point but not quite a spine or thorn, at the tip. As the seed cone continues to grow and expand, the exposed area at the end of each scale grows as well. The larger diamond-shaped area around the umbo, formed in the second year of growth, is called the “apophysis.” The shapes of the prickle, umbo, and apophysis can be helpful in identification. The male and female cones are separate structures, but both are present on the same plant. Pollen is produced by male cones and is carried by the wind to female cones where it fertilizes the ovules. Seeds develop and mature inside the female cones (also called the seed cones) for two years, protected by a series of tightly overlapping woody scales. Some pines open their seed cones after two years to release the seeds, while other pines continue to keep their cones tightly closed past maturity and release seeds in response to the heat of a forest fire.

To learn more about Florida’s pines and helpful hint on identification go to:

http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/fr/fr00300.pdf