by Mark Mauldin | Apr 9, 2021

Spring can be a busy time of year for those of us who are interested in improving wildlife habitat on the property we own/manage. Spring is when we start many efforts that will pay-off in the fall. If you are a weekend warrior land manager like me there is always more to do than there are available Saturdays to get it done. The following comments are simple reminders about some habitat management activities that should be moving to the top of your to-do list this time of year.

Aquatic Weed Management – If you had problematic weeds in you pond last summer, chances are you will have them again this summer. NOW (spring) is the time to start controlling aquatic weeds. The later into the summer you wait the worse the weeds will get and the more difficult they will be to control. The risk of a fish-kill associated with aquatic weed control also increases as water temperatures and the total biomass of the weeds go up. Springtime is “Just Right” for Using Aquatic Herbicides

Cogongrass Control – Spring is actually the second-best time of year to treat cogongrass, fall (late September until first frost) is the BEST time. That said, ideally cogongrass will be treated with herbicide every six months, making spring and fall important. When treating spring regrowth make sure that there are green leaves at least one foot long before spraying. Spring is also an excellent time of year to identify cogongrass patches – the cottony, white blooms are easy to spot. Identify Cogongrass Now – Look for the Seedheads; Cogongrass – Now is the Best Time to Start Control

Cogongrass seedheads are easily spotted this time of year.

Photo credit: Mark Mauldin

Warm-Season Food Pots – There is a great deal of variation in when warm season food plots can be planted. Assuming warm-season plots will be panted in the same areas as cool-season plots, the simplest timing strategy is to simply wait for the cool-season plots to play out (a warm, dry May is normally the end of even the best cool-season plot) and then begin preparation for the warm-season plots. This transition period is the best time to deal with soil pH issues (get a soil test) and control weeds. Seed for many varieties of warm-season legumes (which should be the bulk of your plantings) can be somewhat hard to find, so start looking now. If you start early you can find what you want, and not just take whatever the feed store has. Warm Season Food Plots for White-tailed Deer

Deer Feeders – Per FWC regulations deer feeders need to be in continual operation for at least six months prior to hunting over them. Archery season in the Panhandle will start in mid-October, meaning deer feeders need to be up and running by mid-April to be legal to hunt opening morning. If you have plans to move or add feeders to your property, you’d better get to it pretty soon. FWC Feeding Game

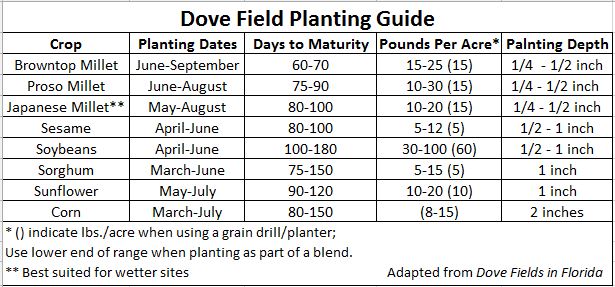

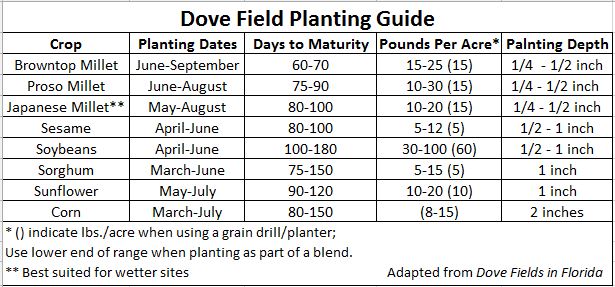

Dove Fields – The first phase of dove season will begin in late September. When you look at the “days to maturity” for the various crops in the chart below you might feel like you’ve got plenty of time. While that may be true, don’t forget that not only do you need time for the crop to mature, but also for seeds to begin to drop and birds to find them all before the first phase begins. Because doves are particularly fond of feeding on clean ground, controlling weeds is a worthwhile endeavor. If you are planting on “new ground”, applying a non-selective herbicide several weeks before you begin tillage is an important first step to a clean field, but it adds more time to the process. As mentioned above, it’s always pertinent to start sourcing seed well in advance of your desired planting date. Timing is Crucial for Successful Dove Fields

There are many other projects that may be more time sensitive than the ones listed above. These were just a few that have snuck up on me over the years. The links in each section will provide more detailed information on the topics. If you have questions about anything addressed in the article feel free to contact me or your county’s UF/IFAS Extension Natural Resource Agent.

by Rick O'Connor | Mar 26, 2021

Six Rivers “Dirty Dozen” Invasive Species

Cogongrass (Imperata cylindrica)

A relatively new patch of cogongrass recently found in Washington County.

Photo Credit: Mark Mauldin

Define Invasive Species: must have all of the following –

- Is non-native to the area, in our case northwest Florida

- Introduced by humans, whether intentional or accidental

- Causing either an environmental or economic problem, possibly both

Define “Dirty Dozen” Species:

These are species that are well established within the CISMA and are considered, by members of the CISMA, to be one of the top 12 worst problems in our area.

Native Range:

Cogongrass is from southeast Asia.

Introduction:

It was accidentally introduced as an “escapee” from satsuma crates brought to Grand Bay, Alabama in 1912. It was later intentionally introduced into Mississippi in the 1920s as a forage crop and then to Florida in the 1930s for both forage and soil stabilization.

EDDMapS currently list 79,134 records of this plant. All are listed in the southeastern U.S. Most are in Florida and Alabama, but there are records from Mississippi, Louisiana, Texas, Georgia, North and South Carolina.

Within our CISMA there are 13,279 records. This is probably underreported.

Description:

Cogongrass is a perennial grass that can vary in color from a bright-light green when young to a brown-orange when older. It does die back in areas with cold winters and heavy frost and becomes brown. The leaves emerge from the ground in clumps and can reach four feet in height. The blades are 0.5-0.75 inches wide and the light-colored midline is off center. The blades are serrated along the edge. In the spring the grass produces large white colored fluffs of seeds extending above the leaves to be carried by the wind. There are numerous small seeds joined on long hairs of these structures. There is an extensive rhizome system beneath the ground that can contribute to short distance spread.

Issues and Impacts:

The plant spreads aggressively and has been found in ditches, along roadsides, in pastures, timberlands, golf courses, empty lots, and even on barrier islands. It spreads both by seed wind dispersal and rhizome fragmentation. The plant is known to be allelopathic, desiccating neighboring plants and moving in. It can form dense monocultures in many areas.

The serrated edges of the leaves make it undesirable as a livestock forage, a fact not detected until the plant was established. It can cover large areas of pasture making it unusable. In the winter the plant becomes brown and can burn very hot. Timberland that has been infested with cogongrass can burn too hot during prescribed burns actually killing the trees.

It is currently listed as one of the most invasive plants in the United States. It is a federal and state noxious weed, it is prohibited all across Florida and has a high invasion risk.

Management:

The key to controlling this plant is destroying the extensive rhizome system. Simple disking has been shown to be effective if you dig during the dry season, when the rhizomes can dry out, and if you disk deep enough to get all of the rhizomes. Though the rhizomes can be found as deep as four feet, most are within six inches and at least a six-inch disking is recommended.

Chemical treatments have had some success. Prometon (Pramitol), tebuthurion (Spike), and imazapyr have all had some success along roadsides and in ditches. However, the strength of these chemicals will impede new growth, or plantings of new plants, for up to six months. This can lead to erosion issues that are undesirable. Glyphosate has been somewhat successful, and its short soil life will allow the planting of new plants immediately. Due to this however, it may take multiple treatments over multiple years to keep cogongrass under control and it will kill other plants if sprayed during treatment.

Most recommend a mixture of burning, disking, and chemical treatment. Disking and burning should be conducted in the summer to remove thatch and all older and dead cogongrass. As new shoots emerge in late summer and early fall herbicides can then be used to kill the young plants. Studies and practice have found complete eradication is difficult. It is also recommended not to attempt any management while in seed (in spring). Tractors, mowers, etc. can collect the seeds and, when the mowers are moved to new locations, spread the problem. If all mowing/disking equipment can be cleaned after treatment – this is highly recommended.

For more information on this Dirty Dozen species, contact your local extension office.

References

Cogongrass, University of Florida IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants

https://plants-archive.ifas.ufl.edu/plant-directory/imperata-cylindrica/

Imperata cylindrica. University of Florida IFAS Assessment.

https://assessment.ifas.ufl.edu/assessments/imperata-cylindrica/.

Early Detection and Distribution Mapping System (EDDMapS)

https://www.eddmaps.org/

Six Rivers CISMA

https://www.floridainvasives.org/sixrivers/

by Sheila Dunning | Jan 28, 2021

Groundhog

Groundhog Day is celebrated every year on February 2, and in 2021, it falls on Tuesday. It’s a day when townsfolk in Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania, gather in Gobbler’s Knob to watch as an unsuspecting furry marmot is plucked from his burrow to predict the weather for the rest of the winter. If Phil does see his shadow (meaning the Sun is shining), winter will not end early, and we’ll have another 6 weeks left of it. If Phil doesn’t see his shadow (cloudy) we’ll have an early spring. Since Punxsutawney Phil first began prognosticating the weather back in 1887, he has predicted an early end to winter

only 18 times. However, his accuracy rate is only 39%. In the south, we call also defer to General Beauregard Lee in Atlanta, Georgia or Pardon Me Pete in Tampa, Florida.

But, what is a groundhog? Are gophers and groundhogs the same animal? Despite their similar appearances and burrowing habits, groundhogs and gophers don’t have a whole lot in common—they don’t even belong to the same family. For example, gophers belong to the family Geomyidae, a group that includes pocket gophers, kangaroo rats, and pocket mice. Groundhogs, meanwhile, are members of the Sciuridae (meaning shadow-tail) family and belong to the genus Marmota. Marmots are diurnal ground squirrels. There are 15 species of marmot, and groundhogs are one of them.

Science aside, there are plenty of other visible differences between the two animals. Gophers, for example, have hairless tails, protruding yellow or brownish teeth, and fur-lined cheek pockets for storing food—all traits that make them different from groundhogs. The feet of gophers are often pink, while groundhogs have brown or black feet. And while the tiny gopher tends to weigh around two or so pounds, groundhogs can grow to around 13 pounds.

While both types of rodent eat mostly vegetation, gophers prefer roots and tubers while groundhogs like vegetation and fruits. This means that the former animals rarely emerge from their burrows, while the latter are more commonly seen out and about. In the spring, gophers make what is called eskers, or winding mounds of soil. The southeastern pocket gopher, Geomys pinetis, is also known as the sandy-mounder in Florida.

Southeastern Pocket Gopher

The southeastern pocket gopher is tan to gray-brown in color. The feet and naked tail are light colored. The southeastern pocket gopher requires deep, well-drained sandy soils. It is most abundant in longleaf pine/turkey oak sandhill habitats, but it is also found in coastal strand, sand pine scrub, and upland hammock habitats.

Gophers dig extensive tunnel systems and are rarely seen on the surface. The average tunnel length is 145 feet (44 m) and at least one tunnel was followed for 525 feet (159 m). The soil gophers remove while digging their tunnels is pushed to the surface to form the characteristic rows of sand mounds. Mound building seems to be more intense during the cooler months, especially spring and fall, and slower in the summer. In the spring, pocket gophers push up 1-3 mounds per day. Based on mound construction, gophers seem to be more active at night and around dusk and dawn, but they may be active at any time of day.

Pocket Gopher Mounds

Many amphibians and reptiles use pocket gopher mounds as homes, including Florida’s unique mole skinks. The pocket gopher tunnels themselves serve as habitat for many unique invertebrates found nowhere else.

So, groundhogs for guesses on the arrival of spring. But, when the pocket gophers are making lots of mounds, spring is truly here. Happy Groundhog’s Day.

by Daniel J. Leonard | Nov 18, 2020

The native Florida landscape definitely isn’t known for its fall foliage. But as you might have noticed, there is one species that reliably turns shades of red, orange, yellow and sometimes purple, it also unfortunately happens to be one of the most significant pest plant species in North America, the highly invasive Chinese Tallow or Popcorn Tree (Triadica sebifera).

Chinese Tallow fall foliage. Photo courtesy of Daniel Leonard.

Native to temperate areas of China and introduced into the United States by Benjamin Franklin (yes, the Founding Father!) in 1776 for its seed oil potential and outstanding ornamental attributes, Chinese Tallow is indeed a pretty tree, possessing a tame smallish stature, attractive bark, excellent fall color and interesting white “popcorn” seeds. In addition, Chinese Tallow’s climate preferences make it right at home in the Panhandle and throughout the Southeast. It requires no fertilizer, is both drought and inundation tolerant, is both sun and shade tolerant, has no serious pests, produce seed preferred by wildlife (birds mostly) and is easy to propagate from seed (a mature

Chinese Tallow tree can produce up to 100,000 seeds annually!). While these characteristics indeed make it an awesome landscape plant and explain it being passed around by early American colonists, they are also the very reasons that make the species is one of the most dangerous invasives – it can take over any site, anywhere.

While Chinese Tallow can become established almost anywhere, it prefers wet, swampy areas and waste sites. In both settings, the species’ special adaptations allow it a competitive advantage over native species and enable it to eventually choke the native species out altogether.

In low-lying wetlands, Chinese Tallow’s ability to thrive in both extreme wet and droughty conditions enable it to grow more quickly than the native species that tend to flourish in either one period or the other. In river swamps, cypress domes and other hardwood dominated areas, Chinese Tallow’s unique ability to easily grow in the densely shaded understory allows it to reach into the canopy and establish a foothold where other native hardwoods cannot. It is not uncommon anymore to venture into mature swamps and cypress domes and see hundreds or thousands of Chinese Tallow seedlings taking over the forest understory and encroaching on larger native tree species. Finally, in waste areas, i.e. areas that have been recently harvested of trees, where a building used to be, or even an abandoned field, Chinese Tallow, with its quick germinating, precocious nature, rapidly takes over and then spreads into adjacent woodlots and natural areas.

Chinese tallow seedlings colonizing a “waste” area. Photo courtesy of Daniel Leonard.

Hopefully, we’ve established that Chinese Tallow is a species that you don’t want on your property and has no place in either landscapes or natural areas. The question now is, how does one control Chinese Tallow?

- Prevention is obviously the first option. NEVER purposely plant Chinese Tallow and do not distribute the seed, even as decorations, as they are sometimes used.

- The second method is physical removal. Many folks don’t have a Chinese Tallow in their yard, but either their neighbors do, or the natural area next door does. In this situation, about the best one can do is continually pull up the seedlings once they sprout. If a larger specimen in present, cut it down as close to the ground as possible. This will make herbicide application and/or mowing easier.

- The best option in many cases is use of chemical herbicides. Both foliar (spraying green foliage on smaller saplings) and basal bark applications (applying a herbicide/oil mixture all the way around the bottom 15” of the trunk. Useful on larger trees or saplings in areas where it isn’t feasible to spray leaves) are effective. I’ve had good experiences with both methods. For small trees, foliar applications are highly effective and easy. But, if the tree is taller than an average person, use the basal bark method. It is also very effective and much less likely to have negative consequences like off-target herbicide drift and applicator exposure. Finally, when browsing the herbicide aisle garden centers and farm stores, look for products containing the active ingredient Triclopyr, the main chemical in brands like Garlon, Brushtox, and other “brush/tree & stump killers”. Mix at label rates for control.

Despite its attractiveness, Chinese Tallow is an insidious invader that has no place in either landscapes or natural areas. But with a little persistence and a quality control plan, you can rid your property of Chinese Tallow! For more information about invasive plant management and other agricultural topics, please contact your local UF/IFAS Extension office!

References:

Langeland, K.A, and S. F. Enloe. 2018. Natural Area Weeds: Chinese Tallow (Sapium sebiferum L.). Publication #SS-AGR-45. Printer friendly PDF version: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/AG/AG14800.pdf

by Sheila Dunning | Oct 16, 2020

That’s the question from a recent group exploring what washed up on the beach after Hurricane Sally.

Sea Cucumber

Photo by: Amy Leath

They have no eyes, nose or antenna. Yet, they move with tiny little legs and have openings on each end. Though scientists refer to them as sea cucumbers, they are obviously animals. Sea cucumbers get their name because of their overall body shape, but they are not vegetables.

There are over 1,200 species of sea cucumbers, ranging in size from ¾“ to more than 6‘ long, living throughout the world’s ocean bottoms. They are part of a larger animal group called echinoderms, which includes starfish, urchins and sand dollars. Echinoderms have five identical parts to their bodies. In the case of sea cucumber, they have 5 elongated body segments separated by tiny bones running from the tube feet at the mouth to the opening of the anus. These squishy invertebrates spend their entire life scavenging off the seafloor. Those tiny legs are actually tube feet that surround their mouth, directing algae, aquatic invertebrates, and waste particles found in the sand into their digestive tract. What goes in, must come out. That’s where it becomes interesting.

Sea cucumbers breathe by dilating their anal sphincter to allow water into the rectum, where specialized organs referred to as respiratory trees (or butt lungs) extract the oxygen from the water before discharging it back into the sea. Several commensal and symbiotic creatures (including a fish that lives in the anus, as well as crabs and shrimp on its skin) hang out on this end of the sea cucumber collecting any “leftovers”.

But, the ecosystem also benefits. Not only is excess organic matter being removed from the seafloor, but the water environment is being enriched. Sea cucumbers’ natural digestion process gives their feces a relatively high pH from the excretion of ammonia, protecting the water surrounding the sea cucumber habitats from ocean acidification and providing fertilizer that promotes coral growth. Also, the tiny bones within the sea cucumber form from the excretion of calcium carbonate, which is the primary ingredient in coral formation. The living and dying of sea cucumbers aids in the survival of coral beds.

When disturbed, sea cucumbers can expose their bony hook-like structures through their skin, making them more pickle than cucumber in appearance. Sea cucumbers can also use their digestive system to ward of predators. To confuse or harm predators, the sea cucumber propels its toxic internal organs from its body in the direction of the attacker. No worries though. They can grow them back again.

Hurricane Sally washed the sea cucumbers ashore so you could learn more about the creatures on the ocean floor. Continue to explore the Florida panhandle outdoor.

by Carrie Stevenson | May 29, 2020

Baby terns on Pensacola Beach are camouflaged in plain sight on the sand. This coloration protects them from predators but can also make them vulnerable to people walking through nesting areas. Photo credit: UF IFAS Extension

The controversial incident recently in New York between a birdwatcher and a dog owner got me thinking about outdoor ethics. Most of us are familiar with the “leave no trace” principles of “taking only photographs and leaving only footprints.” This concept is vital to keeping our natural places beautiful, clean, and safe. However, there are several other matters of ethics and courtesy one should consider when spending time outdoors.

- On our Gulf beaches in the summer, sea turtles and shorebirds are nesting. The presence of this type of wildlife is an integral part of why people want to visit our shores—to see animals they can’t see at home, and to know there’s a place in the world where this natural beauty exists. Bird and turtle eggs are fragile, and the newly hatched young are extremely vulnerable. Signage is up all over, so please observe speed limits, avoid marked nesting areas, and don’t feed or chase birds. Flying away from a perceived predator expends unnecessary energy that birds need to care for young, find food, and avoid other threats.

When on a multi-use trail, it is important to use common courtesy to prevent accidents. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

- On a trail, the rules of thumb are these: hikers yield to equestrians, cyclists yield to all other users, and anyone on a trail should announce themselves when passing another person from behind.

- Obey leash laws, and keep your leash short when approaching someone else to prevent unwanted encounters between pets, wildlife, or other people. Keep in mind that some dogs frighten easily and respond aggressively regardless of how well-trained your dog is. In addition, young children or adults with physical limitations can be knocked down by an overly friendly pet.

- Keep plenty of space between your group and others when visiting parks and beaches. This not only abides by current health recommendations, but also allows for privacy, quiet, and avoidance of physically disturbing others with a stray ball or Frisbee.

Summer is beautiful in northwest Florida, and we welcome visitors from all over the world. Common courtesy will help make everyone’s experience enjoyable.