by Andrea Albertin | Mar 20, 2019

By Vance Crain and Andrea Albertin

Fisherman with a large Shoal Bass in the Apalachicola-Chattahootchee-Flint River Basin. Photo credit: S. Sammons

Along the Chipola River in Florida’s Panhandle, farmers are doing their part to protect critical Shoal Bass habitat by implementing agricultural Best Management Practices (BMPs) that reduce sediment and nutrient runoff, and help conserve water.

Florida’s Shoal Bass

Lurking in the clear spring-fed Chipola River among limerock shoals and eel grass, is a predatory powerhouse, perfectly camouflaged in green and olive with tiger stripes along its body. The Shoal Bass (a species of Black Bass) tips the scale at just under 6 lbs. But what it lacks in size, it makes up for in power. Unlike any other bass, and found nowhere else in Florida, anglers travel long distances for a chance to pursue it. Floating along the swift current, rocks, and shoals will make you feel like you’ve been transported hundreds of miles away to the Georgia Piedmont, and it’s only the Live Oaks and palms overhanging the river that remind you that you’re still in Florida, and in a truly unique place.

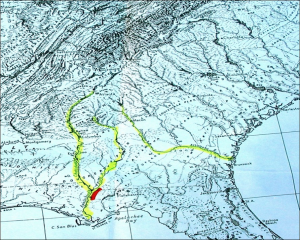

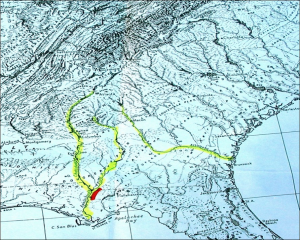

Native to only one river basin in the world, the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint (ACF) River Basin, habitat loss is putting this species at risk. The Shoal Bass is a fluvial specialist, which means it can only survive in flowing water. Dams and reservoirs have eliminated habitat and isolated populations. Sediment runoff into waterways smothers habitat and prevents the species from reproducing.

In the Chipola River, the population is stable but its range is limited. Some of the most robust Shoal Bass numbers are found in a 6.5-mile section between the Peacock Bridge and Johnny Boy boat ramp. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission has turned this section into a Shoal Bass catch and release only zone to protect the population. However, impacts from agricultural production and ranching, like erosion and nutrient runoff can degrade the habitat needed for the Shoal Bass to spawn.

Preferred Shoal Bass habitat, a shoal in the Chipola River. Photo credit: V. Crain

Shoal Bass habitat conservation and BMPs

In 2010, the Southeast Aquatic Resources Partnership (SARP), the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation and a group of scientists (the Black Bass Committee) developed the Native Black Bass Initiative. The goal of the initiative is to increase research and the protection of three Black Bass species native to the Southeast, including the Shoal Bass. It also defined the Shoal Bass as a keystone species, meaning protection of this apex predators’ habitat benefits a host of other threatened and endangered species.

Along the Chipola River, farmers are teaming up with SARP and other partners to protect Shoal Bass habitat and improve farming operations through BMP implementation. A major goal is to protect the river’s riparian zones (the areas along the borders). When healthy, these areas act like sponges by absorbing nutrients and sediment runoff. Livestock often degrade riparian zones by trampling vegetation and destroying the streambank when they go down to a river to drink. Farmers are installing alternative water supplies, like water wells and troughs in fields, and fencing out cattle from waterways to protect these buffer areas and improve water quality. Row crop farmers are helping conserve water in the river basin by using advanced irrigation technologies like soil moisture sensors to better inform irrigation scheduling and variable rate irrigation to increase irrigation efficiency. Cost-share funding from SARP, the USDA-NRCS and FDACS provide resources and technical expertise for farmers to implement these BMPs.

Holstein drinking from a water trough in the field, instead of going down to the river to get water which can cause erosion and problems with water quality. Photo credit: V. Crain

By working together in the Chipola River Basin, farmers, fisheries scientists and resource managers are helping ensure that critical habitat for Shoal Bass remains healthy. Not only is this important for the species and resource, but it will ensure that future generations can continue to enjoy this unique river and seeing one of these fish. So the next time you catch a Shoal Bass, thank a farmer.

For more information about BMPs and cost-share opportunities available for farmers and ranchers, contact your local FDACS field technician: https://www.freshfromflorida.com/Divisions-Offices/Agricultural-Water-Policy/Organization-Staff and NRCS field office USDA-NRCS field office: https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/main/fl/contact/local/ For questions regarding the Native Black Bass Initiative or Shoal Bass habitat conservation, contact Vance Crain at vance@southeastaquatics.net

Vance Crain is the Native Black Bass Initiative Coordinator for the Southeast Aquatic Resource Partnership (SARP).

by Sheila Dunning | Dec 19, 2018

Throughout history the evergreen tree has been a symbol of life. “Not only green when summer’s here, but also when it’s cold and dreary” as the Christmas carol “O Tannenbaum” says. After such devastating tree losses in the Panhandle this year, this winter is a prime time for installing more native evergreens.

Throughout history the evergreen tree has been a symbol of life. “Not only green when summer’s here, but also when it’s cold and dreary” as the Christmas carol “O Tannenbaum” says. After such devastating tree losses in the Panhandle this year, this winter is a prime time for installing more native evergreens.

While supporting the cut Christmas tree industry does create jobs and puts money into local economics, every few years considering adding to the urban forest by purchasing a living tree. Native evergreen trees such as Redcedar make a nice Christmas tree that can be planted following the holidays. The dense growth and attractive foliage make Redcedar a favorite for windbreaks, screens and wildlife cover. The heavy berry production provides a favorite food source for migrating Cedar Waxwing birds. Its high salt-tolerance makes it ideal for coastal locations. Their natural pyramidal-shape creates the traditional Christmas tree form, but can be easily pruned as a street tree.

Two species, Juniperus virginiana and Juniperus silicicola are native to Northwest Florida. Many botanists do not separate the two, but as they mature, Juniperus silicicola takes on a softer, more informal look. For those interested in creating a different look, maybe a Holly (Ilex,sp.) or Magnolia with full-to-the-ground branches could be your Christmas tree.

When planning for using a live Christmas tree there are a few things to consider. The tree needs sunlight, so restrict its inside time to less than a week. Make sure there is a catch basin for water under the tree, but never allow water to remain in the tray and don’t add fertilizer. Locate your tree in the coolest part of the room and away from heating ducts and fireplaces. After Christmas, install the new tree in an open, sunny part of the yard. After a few years you will be able to admire the living fence with all the wonderful memories of many years of holiday celebrations. Don’t forget to watch for the Cedar Waxwings in the Redcedar.

by Sheila Dunning | Nov 9, 2018

As the trees begin to turn various shades of red, many people begin to inquire about the Popcorn trees. While their autumn coloration is one of the reasons they were introduced to the Florida environment, it took years for us to realize what a menace Popcorn trees have become. Triadica sebifera, the Chinese tallowtree or Popcorn tree, was introduced to Charleston, South Carolina in the late 1700s for oil production and use in making candles, earning it another common name, the Candleberry tree. Since then, it has spread to every coastal state from North Carolina to Texas, and inland to Arkansas. In Florida it occurs as far south as Tampa. It is most likely to spread to wildlands adjacent to or downstream from areas landscaped with Triadica sebifera, displacing other native plant species in those habitats. Therefore, Chinese tallowtree was listed as a noxious weed by the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services Noxious Weed List (5b-57.007 FAC) in 1998, which means that possession with the intent to sell, transport, or plant is illegal in the state of Florida. The common name of Florida Aspen is sometimes used to market Popcorn tree in mail-order ads. Remember it’s still the same plant.

As the trees begin to turn various shades of red, many people begin to inquire about the Popcorn trees. While their autumn coloration is one of the reasons they were introduced to the Florida environment, it took years for us to realize what a menace Popcorn trees have become. Triadica sebifera, the Chinese tallowtree or Popcorn tree, was introduced to Charleston, South Carolina in the late 1700s for oil production and use in making candles, earning it another common name, the Candleberry tree. Since then, it has spread to every coastal state from North Carolina to Texas, and inland to Arkansas. In Florida it occurs as far south as Tampa. It is most likely to spread to wildlands adjacent to or downstream from areas landscaped with Triadica sebifera, displacing other native plant species in those habitats. Therefore, Chinese tallowtree was listed as a noxious weed by the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services Noxious Weed List (5b-57.007 FAC) in 1998, which means that possession with the intent to sell, transport, or plant is illegal in the state of Florida. The common name of Florida Aspen is sometimes used to market Popcorn tree in mail-order ads. Remember it’s still the same plant.

Although Florida is not known for the brilliant fall color enjoyed by other northern and western states, we do have a number of trees that provide some fall color for our North Florida landscapes. Red maple, Acer rubrum, provides brilliant red, orange and sometimes yellow leaves. The native Florida maple, Acer floridum, displays a combination of bright yellow and orange color during fall. And there are many Trident and Japanese maples that provide striking fall color. Another excellent native tree is Blackgum, Nyssa sylvatica. This tree is a little slow in its growth rate but can eventually grow to seventy-five feet in height. It provides the earliest show of red to deep purple fall foliage. Others include Persimmon, Diospyros virginiana, Sumac, Rhus spp. and Sweetgum, Liquidambar styraciflua. In cultivated trees that pose no threat to native ecosystems, Crape myrtle, Lagerstroemia spp. offers varying degrees of orange, red and yellow in its leaves before they fall. There are many cultivars – some that grow several feet to others that reach nearly thirty feet in height. Also, Chinese pistache, Pistacia chinensis, can deliver a brilliant orange display.

Young Trident maple with fall foliage. Photo credit: Larry Williams

There are a number of dependable oaks for fall color, too. Shumardi, Southern Red and Turkey are a few to consider. These oaks have dark green deeply lobed leaves during summer turning vivid red to orange in fall. Turkey oak holds onto its leaves all winter as they turn to brown and are pushed off by new spring growth. Our native Yellow poplar, Liriodendron tulipifera, and hickories, Carya spp., provide bright yellow fall foliage. And it’s difficult to find a more crisp yellow than fallen Ginkgo, Ginkgo biloba, leaves. These trees represent just a few choices for fall color. Including one or several of these trees in your landscape, rather than allowing the Popcorn trees to grow, will enhance the season while protecting the ecosystem from invasive plant pests.

For more information on Chinese tallowtree, removal techniques and native alternative trees go to: http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/ag148.

by Les Harrison | Oct 26, 2018

Lantana, on the left, and Mexican Petunia, on the right, are both exotic invasive plants which can displace many native species and disrupt the natural balance.

Autumn is usually considered the season of colors in the natural parts of north Florida, and other locations in North America. This tonal attribute is commonly credited to the foliage changes as the growing season ends.

Maples, sweet gums, hickory and many others make their contributions to the natural palette of shades and hues which have existed since long before human habitation in the area. Even some of the native plants add to the display.

Goldenrod and dogfennel add highlights to the brilliant display as winter, believe it or not, approaches. Unfortunately there are some attractive shades in the exhibition which are an indication of exotic invasive plants which have pushed out native.

Both lantana and Mexican petunias are currently blooming, but an indication of problem species. Both were introduces as ornamental plants, but quickly escaped into the wild where they could colonize unchecked.

Lantana (Lantana camara) is a woody shrub native to tropical zones of North and South America. It flowers profusely throughout much of the growing season.

Because of the plant’s ornamental nature, many different flower colors exist, but the most frequent color combinations are red and yellow along with purple and white. Lantana is now commonly found in naturalized populations throughout the southeastern United States from Florida to Texas.

It is currently ranked as one of the top ten most troublesome weeds in Florida and has documented occurrences in 58 of 67 counties. Curiously, despite the bad reputation it is still found in home and commercial landscapes.

As part of its arsenal of conquest, Lantana produces allelochemicals, or plant toxins, in its roots and stems. These allelochemicals have been shown to either slow the growth of other plants or totally remove them.

Some of these same chemicals give lantana an acrid taste and deter insects or other animals from consuming the leaves. Of importance to pet and livestock owners, these leaf toxins are damaging to animals.

If animals consume the leaves, they often begin to show symptoms of skin peeling or cracking. Once animals show these symptoms, there is little or no treatment that can reverse the process.

Although lantana’s leaves are poisonous, its berries are not. Birds readily consume the fruit and are responsible for much of the seed’s distribution over wide areas.

Mexican petunia (Ruellia simplex) is a native of Mexico, but also the Antilles and parts of South America. Its tolerance of varying landscape conditions makes it a common choice for difficult to plant areas and has contributed to it popularity and wide use.

Mexican petunia tolerates shade, sun, wet, dry, and poor soil conditions. It is a prolific bloomer with flowers in shades of purple and pink peaking in the summer, but with the potential to also bloom in spring and fall in some parts of Florida.

Environmental tolerance, abundant seed production, and an ability to easily grow from plant cuttings have all promoted the spread into natural areas bordering developments. The Mexican petunia has been credited with “altering native plant communities by displacing native species, changing community structures or ecological functions, or hybridizing with natives” according to the Florida Exotic Pest Plant Council in 2011.

Given the continued popularity of both species, plant breeders have developed sterile, non-reproducing cultivars which do not have the negative characteristics of these problem plants. It is recommended using only the sterile type so autumn’s colors continue to be natural.

To learn more about north Florida’s colorful invasive plants, contact the local UF/IFAS County Extension Office. Click here for contact information.

by Sheila Dunning | Apr 14, 2018

Having just completed the Okaloosa/Walton Uplands Master Naturalist course, I would like to share information from the project that was presented by Ann Foley.

The Florida Torreya. Photo provided by Shelia Dunning

The Florida Torreya is the most endangered tree in North America, and perhaps the world! Less than 1% of the historical population survives. Unless something is done soon, it may disappear entirely! You can see them on public lands in Florida at Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve and beautiful Torreya State Park.

The Florida Torreya (Torreya taxifolia) is one of the oldest known tree species on earth; 160 million years old. It was originally an Appalachian Mountains ranged tree. As a result of our last “Ice Age” melt, retreating Icebergs pushed ground from the Northern Hemisphere, bringing the Florida Torreya and many other northern plant species with them.

The Florida Torreya was “left behind” in its current native pocket refuge, a short 40 mile stretch along the banks of the Apalachicola River. There were estimates of 600,000 to 1,000,000 of these trees in the 1800’s. Torreya State Park, named for this special tree, is currently home to about 600 of them. Barely thriving, this tree prefers a shady habitat with dark, moist, sandy loam of limestone origin which the park has to offer.

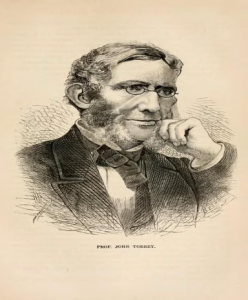

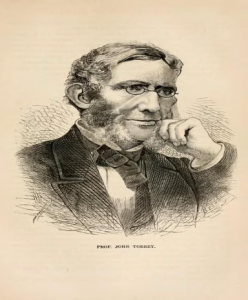

Hardy Bryan Croom, Botanist, discovered the tree in 1833, along the bluffs and ravines of Jackson, Liberty and Gadsen Counties, Florida and Decatur County in Georgia. He named it Florida Torreya (TOR-ee-uh), in honor of Dr. John Torrey, a renowned 18th century scientist.

Torreya trees are evergreen conifers, conically shaped, have whorled branches and stiff, sharp pointed, dark green needle-like leaves. Scientists noted the Torreya’s decline as far back as the 1950’s! Mature tree heights were once noted at 60 feet, but today’s trees are immature specimens of 3-6 feet, thought to be ‘root/stump sprouts.’

Known locally as “Stinking Cedar,” due to its strong smell when the leaves and cones are crushed, it was used for fence posts, cabinets, roof shingles, Christmas trees and riverboat fuel. Over-harvesting in the past and natural processes are taking a tremendous toll. Fungi are attacking weakened trees, causing the critically endangered species to die-off. Other declining factors include: drought, habitat loss, deer and loss of reproductive capability.

With federal and state protection, the Florida Torreya was listed as an endangered species in 1983. There is great concern for this ancient tree in scientific community and with citizen organizations. Efforts are underway to help bring this tree back from the edge of extinction!

Efforts include CRISPR gene editing technology research being done by the University of Florida Dept. of Forest Resources and Conservation- making the tree more resistant to disease. Torreya Guardians “rewilding and “assisted migration”. Reintroducing the tree to it’s former native range in the north near the Biltmore Estate in Asheville, NC, which has maintained a grove of Torreya trees and offspring since 1939 and supplying seeds for propagation from their healthy forest. Long before saving the earth became a global concern, Dr. Seuss (Theodor Seuss Geisel), spoke through his character the Lorax warning against urban progress and the danger it posed to the earth’s natural beauty. All of these groups, and many others, hope their efforts will collectively help bring this tree back from the brink!

by Sheila Dunning | Jan 19, 2018

The Florida Master Naturalist Program is an adult education University of Florida/IFAS Extension program. Training will benefit persons interested in learning more about Florida’s environment or wishing to increase their knowledge for use in education programs as volunteers, employees, ecotourism guides, and others.

The Florida Master Naturalist Program is an adult education University of Florida/IFAS Extension program. Training will benefit persons interested in learning more about Florida’s environment or wishing to increase their knowledge for use in education programs as volunteers, employees, ecotourism guides, and others.

Through classroom, field trip, and practical experience, each module provides instruction on the general ecology, habitats, vegetation types, wildlife, and conservation issues of Coastal, Freshwater and Upland systems. Additional special topics focus on Conservation Science, Environmental Interpretation, Habitat Evaluation, Wildlife Monitoring and Coastal Restoration. For more information go to: http://www.masternaturalist.ifas.ufl.edu/ Okaloosa and Walton Counties will be offering Upland Systems on Thursdays from February 15- March 22. Topics discussed include Hardwood Forests, Pinelands, Scrub, Dry Prairie, Rangelands and Urban Green Spaces. The program also addresses society’s role in uplands, develops naturalist interpretation skills, and discusses environmental ethics. Check the website for a Course Offering near you :http://conference.ifas.ufl.edu/fmnp/