by Thomas Derbes II | Nov 8, 2024

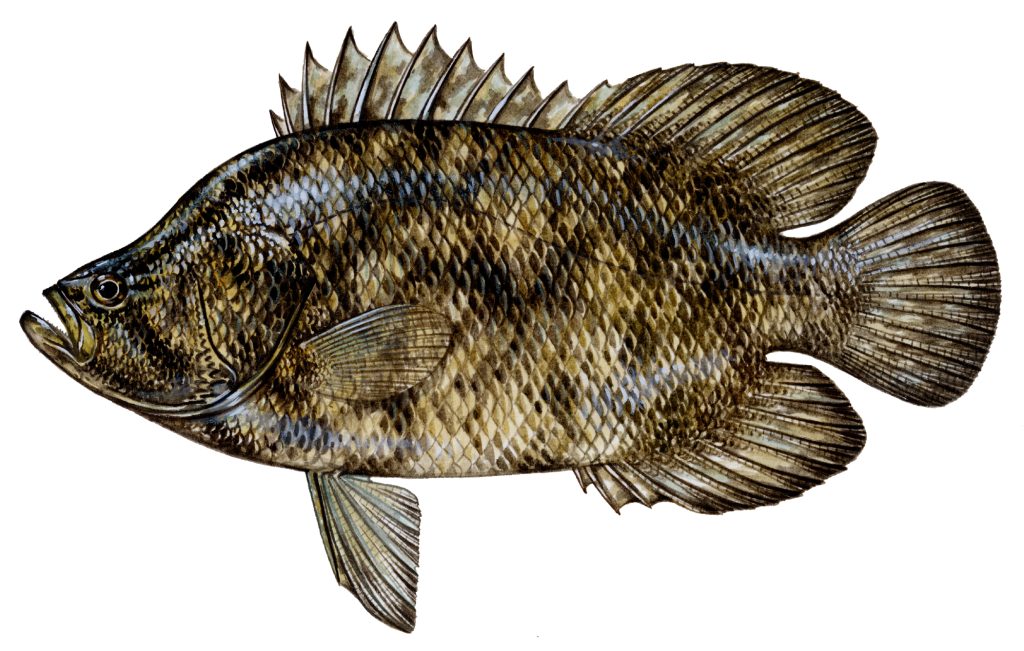

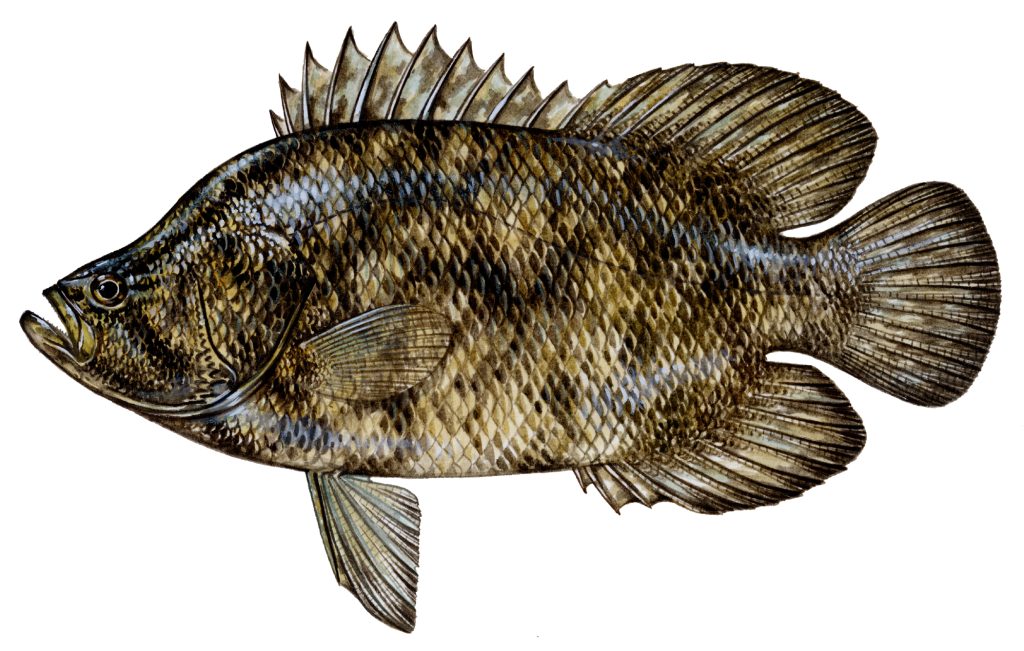

The Atlantic Tripletail (Lobotes surinamensis) is a very prized sportfish along the Florida Panhandle. Typically caught as a “bonus” fish found along floating debris, the tripletail is a hard fighting fish and excellent table fare. Just as the name implies, this fish is equipped with three “tails” that help aid it in propulsion; and also help contribute to their strong fighting spirit. In addition to the caudal fin, tripletail have very pronounced “lobed” dorsal and anal fin soft rays that sit very far back on the body, giving it the appearance of three tails (triple-tails).

Atlantic Tripletail (Lobotes surinamensis) – FWC, Diane Rome Peebles 1992

Tripletail are found in tropical and subtropical seas around the world (except the eastern Pacific Ocean) and are the only member of their family found in the Gulf of Mexico. Tripletail can be found in all saltwater environments, from the upper bays to the middle of the Gulf of Mexico. In the Florida Panhandle, tripletail begin to show up in the bays beginning in May and can be found up until October/November. They are masters of disguise, usually found floating along floating debris, crab trap buoys, navigation pilings, and floating algae like Sargassum. When tripletail are young, they are able to change their colors to match the debris, albeit it is usually a variation of yellow, brown, and black. Adult tripletail can change color as well, but the coloration is not as vibrant as the juveniles. Floating alongside debris and other floating materials protects them from predators and gives them food access. Small crustaceans, like shrimp and crabs, and small fish will gather along the floating debris, looking for protection, giving the camouflaged tripletail an easy meal.

Baby Tripletail or Leaf? – Thomas Derbes II

Tripletail are opportunistic feeders that are what I classify as “lazy hunters.” Tripletail will hang out along any floating debris and wait for the food to come to them. They typically will not chase their prey items too far and will abandon the hunt if they expend too much energy. Since they are opportunistic feeders, their diet varies widely, but they cannot resist a baby blue crab, shrimp, or small baitfish like menhaden (Brevoortia patronus) that might visit their floating oasis. When further offshore, it is not uncommon to find many tripletail “laying out” on sargassum or floating debris. I personally have seen a dozen full-sized tripletail inside of a large traffic barrel 25 miles offshore that saved a skunk of a deep-dropping fishing trip.

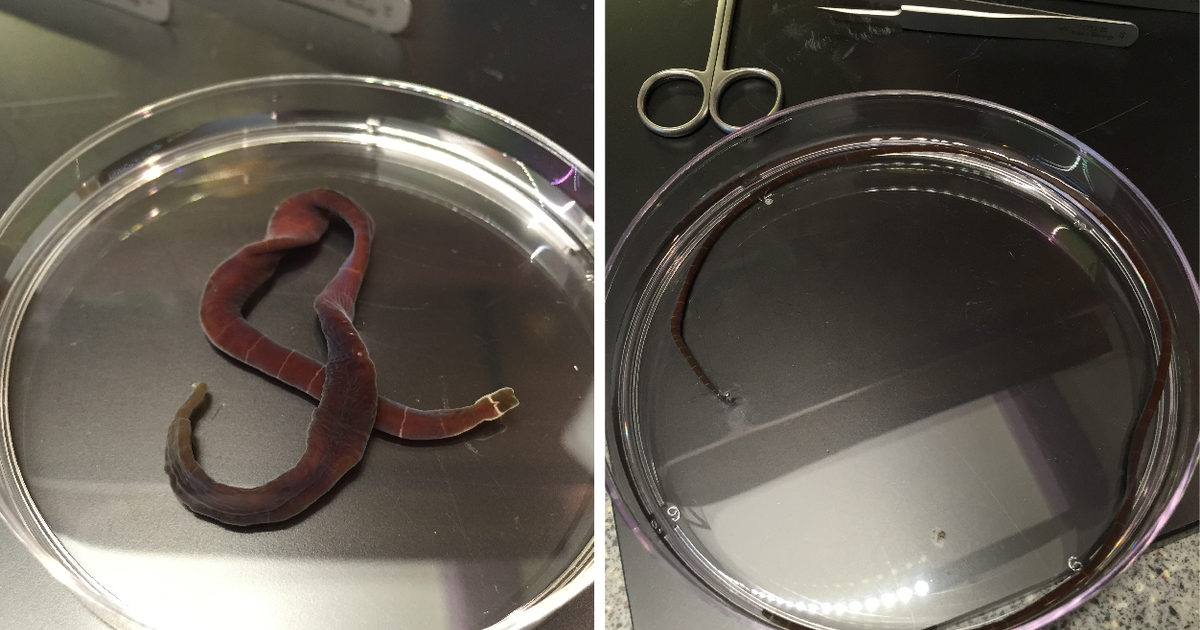

Tripletail Caught Off An Oyster Farm – Brandon Smith

When targeting tripletail, anglers will typically sit at the highest point of the boat (some anglers have towers for spotting tripletail) and cruise along floating crab trap buoys, pilings, and sometimes oyster farms looking for Tripletail. These fish are very easily spooked, and a slow, quiet approach is best. Once in casting distance, toss your preferred bait (I typically want to have baby crabs or live shrimp when targeting tripletail) close to the floating structure, but not too close to spook the fish. You can usually watch the fish eat your bait (another added bonus) and once you set the hook, the fight is on! In the state of Florida, tripletail must be a minimum of 18 inches and there is a daily bag limit of 2 fish per person. Be very careful handling tripletail as they have very sharp dorsal and anal fins and their operculum (gill cover) is also very sharp with hidden spines.

So next time you’re out fishing and see something floating, make sure you give it a good look over. There might be a camouflaged tripletail that you can add to your fish box!

Tripletail Caught While Working Oyster Gear – Thomas Derbes

by Rick O'Connor | Aug 30, 2024

Introduction

The bay scallop (Argopecten irradians) was once common in the lower portions of the Pensacola Bay system. However, by 1970 they were all but gone. Closely associated with seagrass, especially turtle grass (Thalassia testudinum), some suggested the decline was connected to the decline of seagrass beds in this part of the bay. Decline in water quality and overharvesting by humans may have also been a contributor. It was most likely a combination of these factors.

Scalloping is a popular activity in our state. It can be done with a simple mask and snorkel, in relatively shallow water, and is very family friendly. The decline witnessed in the lower Pensacola Bay system was witnessed in other estuaries along Florida’s Gulf coast as well. Today commercial harvest is banned, and recreational harvest is restricted to specific months and to the Big Bend region of the state. With the improvements in water quality and natural seagrass restoration, it is hoped that the bay scallop may return to lower Pensacola Bay.

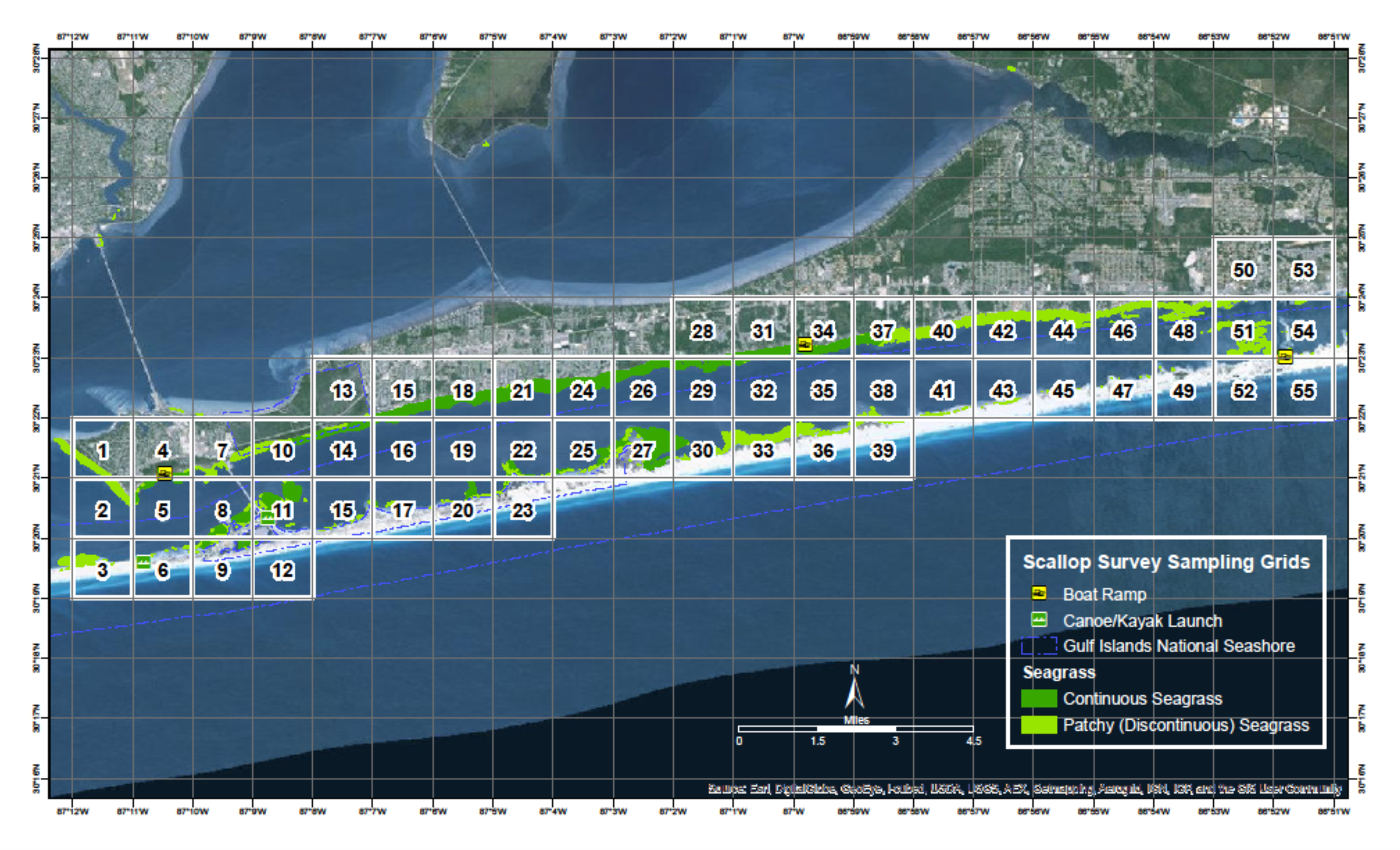

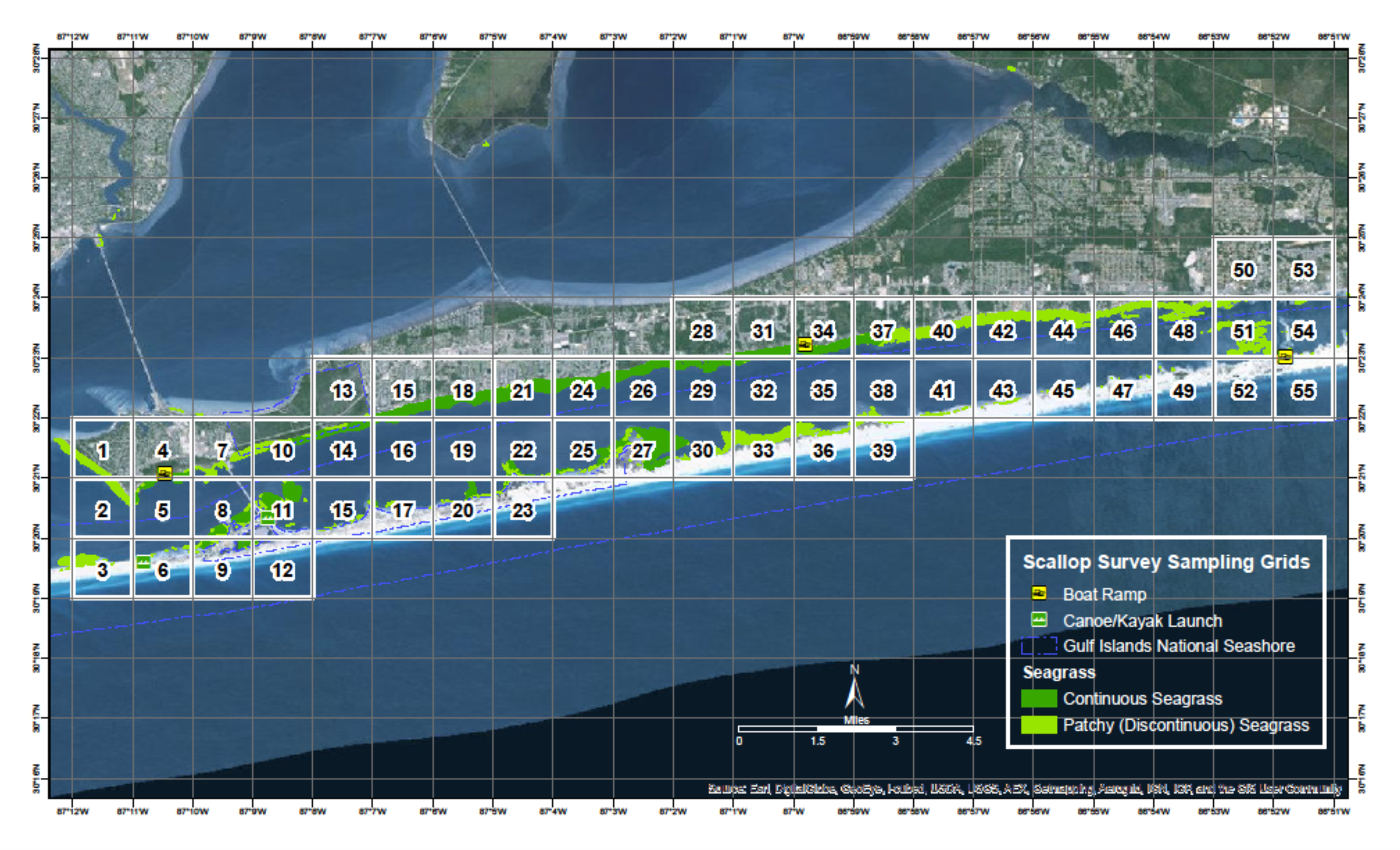

Since 2015 Florida Sea Grant has held the annual Pensacola Bay Scallop Search. Trained volunteers survey pre-determined grids within Big Lagoon and Santa Rosa Sound. Below is the report for both the 2024 survey and the overall results since 2015.

Methods

Scallop searchers are volunteers trained by Florida Sea Grant. Teams are made up of at least three members. Two snorkel while one is the data recorder. More than three can be on a team. Some pre-determined grids require a boat to access, others can be reached by paddle craft or on foot.

Once on site the volunteers extend a 50-meter transect line that is weighted on each end. Also attached is a white buoy to mark the end of the line. The two snorkelers survey the length of the transect, one on each side, using a 1-meter PVC pipe to determine where the area of the transect ends. This transect thus covers 100m2. The surveyors record the number of live scallops they find within this area, measure the height of the first five found in millimeters using a small caliper, which species of seagrass are within the transect, the percent coverage of the seagrass, whether macroalgae are present or not, and any other notes of interest – such as the presence of scallop shells or scallop predators (such as conchs and blue crabs). Three more transects are conducted within the grid before returning.

The Pensacola Scallop Search occurs during the month of July.

2024 Results

A record 168 volunteers surveyed 15 of the 66 1-nautical mile grids (23%) between Big Lagoon State Park and Navarre Beach. 152 transects (15,200m2) were surveyed logging 133 scallops. An additional 50 scallops were found outside the official transect for a total of 183 scallops for 2024.

2024 Big Lagoon Results

75 volunteers surveyed 7 of the 11 grids (64%) within the Big Lagoon. 67 transects were conducted covering 6,700m2.

101 scallops were logged with an additional 42 found outside the official transects. This equates to 3.02 scallops/200m2. Scallop searchers reported blue crabs and conchs, both scallop predators, as well as some sea urchins. All three species of seagrass were found (Thalassia, Halodule, and Syringodium). Seagrass densities ranged from 5-100%. Macroalgae was present in six of the seven grids (86%) but was never abundant.

2024 Santa Rosa Sound Results

93 volunteers surveyed 8 of the 55 grids (14%) in Santa Rosa Sound. 85 transects were conducted covering 8,500m2.

32 scallops were logged with an additional 8 found outside the official transects. This equates to 0.76 scallops/200m2. Scallop searchers reported blue crabs, conchs, and sand dollars. All three species of seagrass were found. Seagrass densities ranged from 50-100%. Macroalgae was present in five of the eight grids (62%) and was abundant in grids surveyed on the eastern end of the survey area.

2015 – 2024 Big Lagoon Results

| Year |

No. of Transects |

No. of Scallops |

Scallops/200m2 |

| 2015 |

33 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2016 |

47 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2017 |

16 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2018 |

28 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2019 |

17 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2020 |

16 |

1 |

0.12 |

| 2021 |

18 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2022 |

38 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2023 |

43 |

2 |

0.09 |

| 2024 |

67 |

101 |

3.02 |

| Big Lagoon Overall |

323 |

104 |

0.64 |

2015 – 2024 Santa Rosa Sound Results

| Year |

No. of Transects |

No. of Scallops |

Scallops/200m2 |

| 2015 |

01 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2016 |

01 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2017 |

01 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2018 |

01 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2019 |

01 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2020 |

01 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2021 |

20 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2022 |

40 |

2 |

0.11 |

| 2023 |

28 |

2 |

0.14 |

| 2024 |

85 |

32 |

0.76 |

| Santa Rosa Sound Overall |

1731 |

36 |

0.42 |

1 Transects were conducted during these years but data for Santa Rosa Sound was logged by an intern with the Santa Rosa County Extension Office and is currently unavailable.

Discussion

Based on a Florida Fish and Wildlife Research Institute publication in 2018, the final criteria are used to classify scallop populations in Florida.

| Scallop Population / 200m2 |

Classification |

| 0-2 |

Collapsed |

| 2-20 |

Vulnerable |

| 20-200 |

Stable |

Based on this, over the last nine years we have surveyed, the populations in lower Pensacola Bay are still collapsed. However, you will notice that in 2024 the population in Big Lagoon moved from collapsed to vulnerable for this year alone.

There are some possible explanations for this.

- The survey effort in Big Lagoon was stronger than Santa Rosa Sound. 75 volunteers surveyed 7 of the 11 grids. This equates to 11 volunteers / grid surveyed and 64% of the survey area was covered. With Santa Rosa Sound there were 93 volunteers who surveyed 8 of the 55 grids. This equates to 12 volunteers / grid surveyed but only 14% of the survey area was covered. Most of the SRS grids surveyed were in the Gulf Breeze/Pensacola Beach area. More effort east of Big Sabine may yield more scallops found.

- There is the possibility of different teams counting the same scallops. Each grid is 1-nautical mile, so the probability of one team laying their transect over an area another team did is low, but not zero.

- It is known that scallops have periodic population booms. Our search this year may have witnessed this. We will know if encounters significantly decrease in 2025.

Whether there was double counting this year or not, the frequency of encounter was much higher than in previous years. There were multiple reports from the public on social media about scallop encounters as well, and in some places we did not survey. It is also understood that scallops mass spawn. So, high density populations are required for reproductive success. The “boom” we witnessed this year suggests that there is a population of scallops – albeit a collapsed one – in our bay. It is important for locals NOT to harvest scallops from either body of water. First, it is illegal. Second, any chance of recovering this lost population will be lost if the adult population densities are not high enough for reproductive success.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank ALL 168 volunteers who surveyed this year. We obviously could not have done this without you.

Below are the “team captains”.

Harbor Amiss Glen Grant Eric Stone

David Anderson Phil Harter Neil Tucker

Laura Baker Gina Hertz Christian Wagley

Melinda Bennett Sean Hickey Jaden Wielhouwer

Samantha Bergeron (USM class) John Imhof Keith Wilkins

Cheri Bone Jason Mellos Christy Woodring

Cindi Cagle Greg Patterson

Cher Clary Kelly Rysula

A team of scallop searchers celebrates after finding a few scallops in Pensacola Bay.

Volunteer measures a scallop he found. Photo: Abby Nonnenmacher

Rick O’Connor Florida Sea Grant; Escambia County

Thomas Derbes II Florida Sea Grant; Santa Rosa County

by Thomas Derbes II | Aug 23, 2024

Oysters are not only powerful filterers, they also provide a home and habitat for many marine organisms. Most of these organisms will fall off while the oysters are being harvested or cleaned, but some will stay behind and can be found inside or outside of your oyster on the half shell. Seeing some of these creatures might give you the “heebie jeebies” about eating the oyster, they are perfectly safe and can either be removed or, in some cases, consumed for luck. These creatures include mud worms (Polydora websteri), “pea crabs” (Pinnotheres ostreum or Zaops ostreus), and “mud crabs” (Panopeus herbstii, Hexapanopeus angustifrons or Rhithropanopeus harrisii).

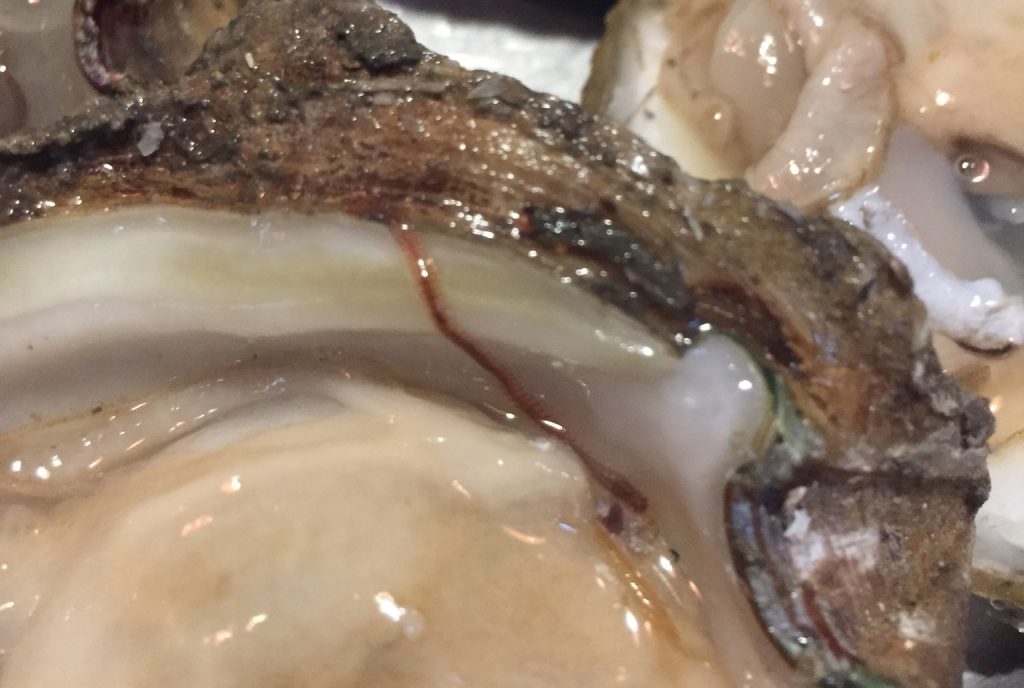

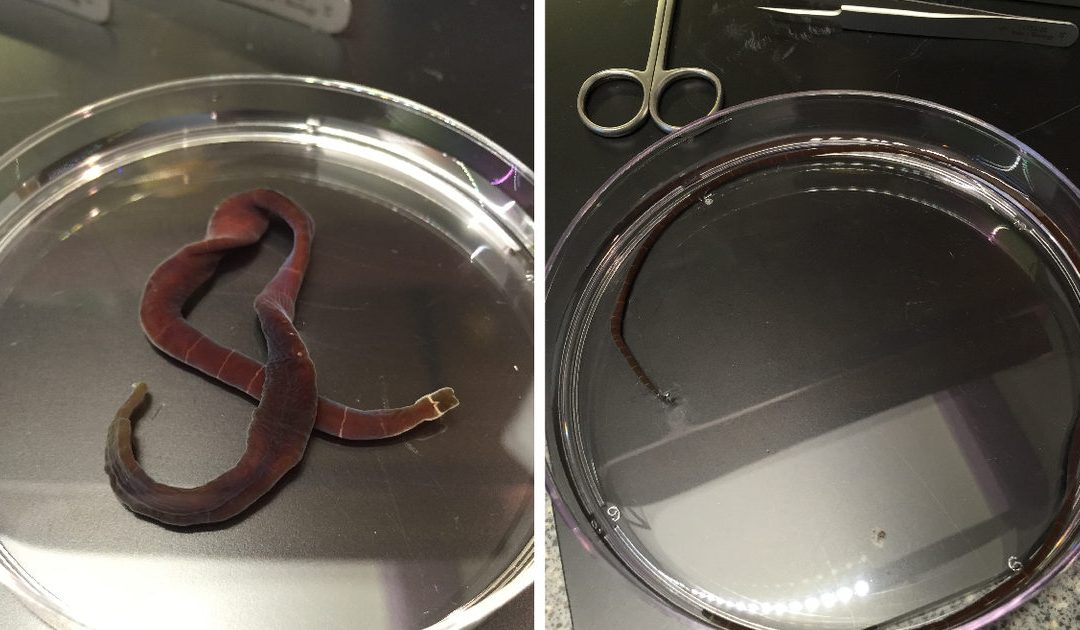

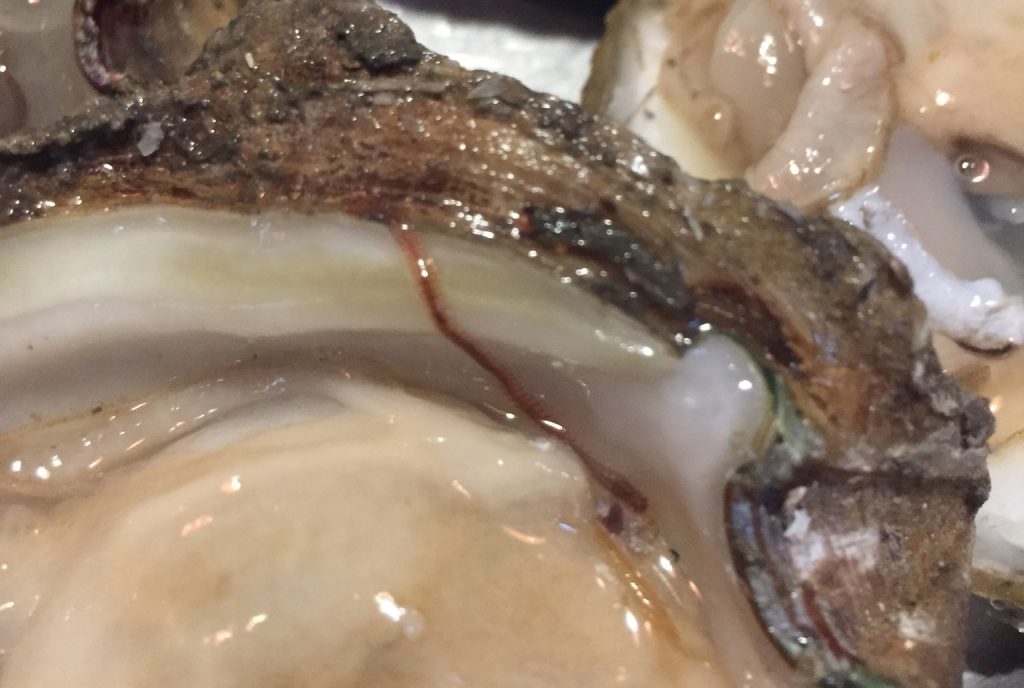

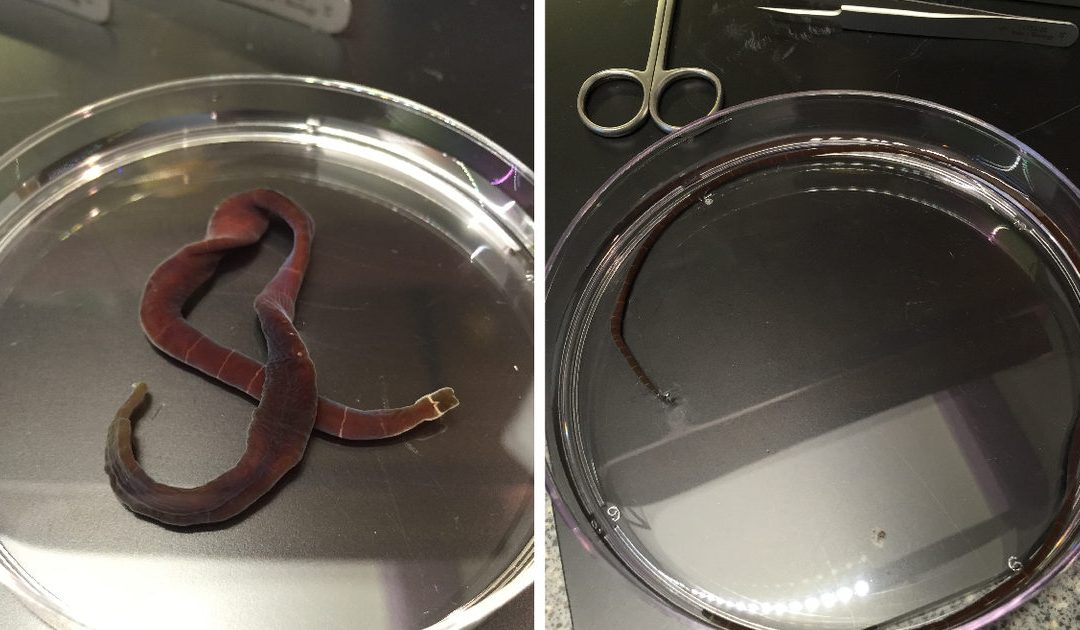

Mud Worms (Polydora websteri)

A Mud Worm in an Oyster – Louisiana Sea Grant

One of the more common marine organisms you can find on an oyster is the oyster mud worm. These worms are typically red in color and form a symbiotic relationship with the oyster. Mud worms can be found in both farmed and wild harvest oysters throughout the United States. These worms will typically form a “mud blister” and emerge when the oyster has been harvested. Even though the worms look menacing and unsightly, they are a sign of a fresh harvest and a good environment. Mud worms do not pose any threat to humans and can be consumed.

If you find a mud worm on your next oyster and are still unsure, just simply remove the worm and dispose of it. Dr. John Supan, retired professor and past director of Louisiana Sea Grant’s Oyster Research Laboratory on Grand Isle, mentioned in an article that oyster mud worms “are absolutely harmless and naturally occurring,” and “if a consumer is offended by it while eating raw oysters, just wipe it off and ask your waiter/waitress for another napkin. Better yet, if there are children at the table, ask for a clear glass of water to drop the worm in. They are beautiful swimmers and can be quite entertaining.”

“Pea Crabs” (Pinnotheres ostreum or Zaops ostreus)

“Pea Crabs” are in fact two different species of crabs lumped together under one name. Pea crabs include the actual pea crab (Pinnotheres ostreum) and the oyster crab (Zaops ostreus). These crabs are so closely associated with oysters that their species name contains some form of the Latin word “ostreum” meaning oyster! Pea crabs are known as kleptoparasites and will embed themselves into the gills of an oyster and steal food from the host oyster. Even though they steal food, they seem to pose no threat to the oyster and are a sign of a healthy marine ecosystem.

A Cute Little Pea Crab – (C)2013 T. Michael Williams

Pea crabs are soft-bodied and round, giving them the pea name. Pea crabs can be found throughout the Atlantic coast, but are more concentrated in coastal areas from Georgia to Virginia. While they might look like an alien from another planet, they are considered a delicacy and are typically consumed along with the oyster. If you are brave enough to slurp down a pea crab, you might just be rewarded with a little luck. According to White Stone Oysters, “historians and foodies alike agree that finding a pea crab isn’t just a small treat, it’s also a sign of good luck!”

“Mud Crabs” (Panopeus herbstii, Hexapanopeus angustifrons or Rhithropanopeus harrisii)

Smooth Mud Crab – Florida Shellfish Lab

Just like pea crabs, “mud crabs” is another name for two different species of crabs commonly found in oysters. These crabs, the Harris Mud Crab (Rhithropanopeus harrisii), Smooth Mud Crab (Hexapanopeus angustifrons), and the Atlantic mud crab (Panopeus herbstii) to name just a few, reach a maximum size of 2 to 8 centimeters and are hard-bodied, unlike the pea crabs. Mud crabs can survive a wide range of salinities, but need cover to survive as these crabs are common prey for most of the oyster habitat dwellers, such as catfish (Ariopsis felis), redfish (Sciaenops ocellatus), and sheepshead (Archosargus probatocephalus). These crabs are not beneficial to an oyster environment as they will seek out young oysters and consume them by breaking the shell with their strong claws. If you find a mud crab in your oyster, this is one to dispose of before consuming. However, these crabs typically live on the outside of an oyster and are typically only found when you buy a sack of oysters and do not have an effect on the quality of the oyster.

Don’t Be Afraid

Hopefully this article has helped shed some light on the creatures you might experience when shucking or consuming oysters. Here is a helpful online tool to help identify some marine organisms associated with clam and oyster farms (Click Here). While most of the organisms can be consumed, we recommend the mud crabs be disposed of due to their hard shells. Remember, some of these organisms can bring you luck and with college football season around the corner, some of us might need all the luck we can get! Bring on the pea crabs!

References Hyperlinked Above

by Thomas Derbes II | Aug 10, 2024

Many of us are given that Birds and the Bees talk; another majority have had to give it as an adult to their kids. It is usually an awkward talk, but someone had to step up to the plate and put on a straight face. I am happy to be the one today to discuss one section of the Birds and the Bees of the Sea, batch spawning. Batch spawning, also known as broadcast spawning, is the coordinated release of gametes (sperm and eggs) into the water column. Batch spawning is not just relegated to fish, many species of invertebrates also batch spawn. Some of the most commonly encountered batch spawners include Florida Pompano (Trachinotus carolinus), Eastern Oyster (Crassostrea virginica), Red Drum (Sciaenops ocellatus), Red Snapper (Lutjanus campechanus), and Gag Grouper (Mycteroperca microlepis), to name a few. In fact, most gamefish species in the Gulf of Mexico are batch spawners. This has its advantages, but also has its major disadvantages. We will dive headfirst into a few representative species of saltwater organisms that batch spawn, and their respective life stages to help shed some light on reproduction in the marine world.

Baby Snapper – Thomas Derbes II

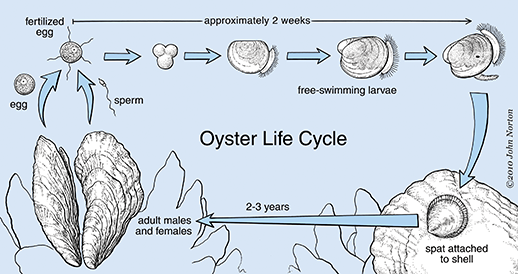

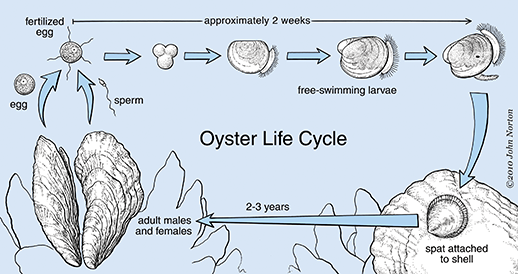

Eastern Oysters are a perfect representative for invertebrate batch spawning. I have gone over their life cycle in a previous article (Click Here), but I will just quickly go over their spawning habits and life history. Eastern Oysters typically spawn during the changing of the seasons, particularly from Spring to Summer and Summer to Fall. As humans, we see these changing temperatures and weather fronts as an opportunity for a new wardrobe, but these changes are triggers for oysters to spawn. Once one oyster releases their gametes into the water all of the mature oysters in the area will start releasing their gametes. Waiting to sense for other gametes in the water is a very smart tactic. This allows for a coordinated spawn between masses of oysters and (hopefully) increases the fertilization rate of the eggs. Since oysters cannot move, batch spawning is the most beneficial way for them to reproduce. Females can release anywhere from 2 to 70 million eggs in one spawning event, with only a dozen or so becoming adults. Since they are batch spawners, the larvae are left unprotected by the parents and suspended in the water column for the first few weeks, leaving them susceptible to predation by filter feeders and bad water quality. Once the larvae have reached the pediveliger stage, they will settle out and “walk” along the bottom of the estuary until they find a suitable place to call home, usually another oyster or hard substrate. After 1-3 years, the oyster will mature and begin batch spawning when conditions are ripe, and the cycle continues!

The Oyster Life Cycle – Maryland Sea Grant

Fish in the Lutjanidae (snapper) family are the perfect representative for batch spawning with fish. Snappers of all species are known to congregate and have mass spawning events typically around a full moon. The mutton snapper (Lutjanus analis) of South Florida and the Florida Keys are very well known for their ability to form massive congregations of tens of thousands of fish along the reef starting in April. Once the spawning commences, the mutton snapper will form a small subgroup of up to 20 fish in the late afternoon. This subgroup will travel to depths of up to 100ft to perform their spawning event. During this event, the female will signal to the males that she is about to release her eggs. The males will then rub up against the side of the female snapper, helping her release eggs while simultaneously releasing their milt (sperm). When the milt is released, the sperm is activated by the seawater and begins to swim. Eventually, the eggs are fertilized and an embryo is formed.

Massive Two-spot red snapper aggregation ready to spawn in Palau – R.J. Hamilton

18 – 24 hours later, the embryo is now a larval fish consisting of a yolk sac and lacking a mouth, eyes, and most organs. The yolk sac consists of amino acids and other nutrients that provide energy to the developing larvae. These larval fish have until their yolk sac runs out to develop the lacking vital organs, which usually takes between 24 – 48 hours. Only a very small percent of juvenile snapper make it to adulthood due to predation during their larval stage and predation as a juvenile. In fact, sharks and other large predators will prey on the snapper as they congregate and spawn, and filter feeders like manta rays are known to pass through an active spawning congregation to consume all the fertilized eggs and larval fish.

Well, I hope I didn’t scar anyone too badly. Batch spawning is fairly common in the marine biology world, and you can sometimes experience a spawning event without even knowing it. As for positives, this allows for many eggs to be fertilized at a time multiple times a season and for the larval fish and shellfish to be distributed through the estuary and reef via tides and waves. A major negative is the vulnerability of the juvenile and larval fish and shellfish, but the sheer number of eggs produced and fertilized helps outweigh the high potential for predation and unexplained loss of fertilized eggs and juveniles.

References:

Oyster Spawning: https://www.umces.edu/news/the-life-of-an-oyster-spawning

Mutton Snapper Species Spawning Profile: https://geo.gcoos.org/restore/species_profiles/Mutton%20Snapper/

Mutton Snapper Aquaculture Profile: https://srac.msstate.edu/pdfs/Fact%20Sheets/725%20Species%20Profile-%20Mutton%20Snapper.pdf

by Rick O'Connor | Aug 10, 2024

I bet that for most of you, this is not only a worm you have never seen – it is a worm you have never heard of before. I learned about them first in college, which was almost 50 years ago, and have never seen one. But, other than the earthworm, the world of worms is basically hidden from us.

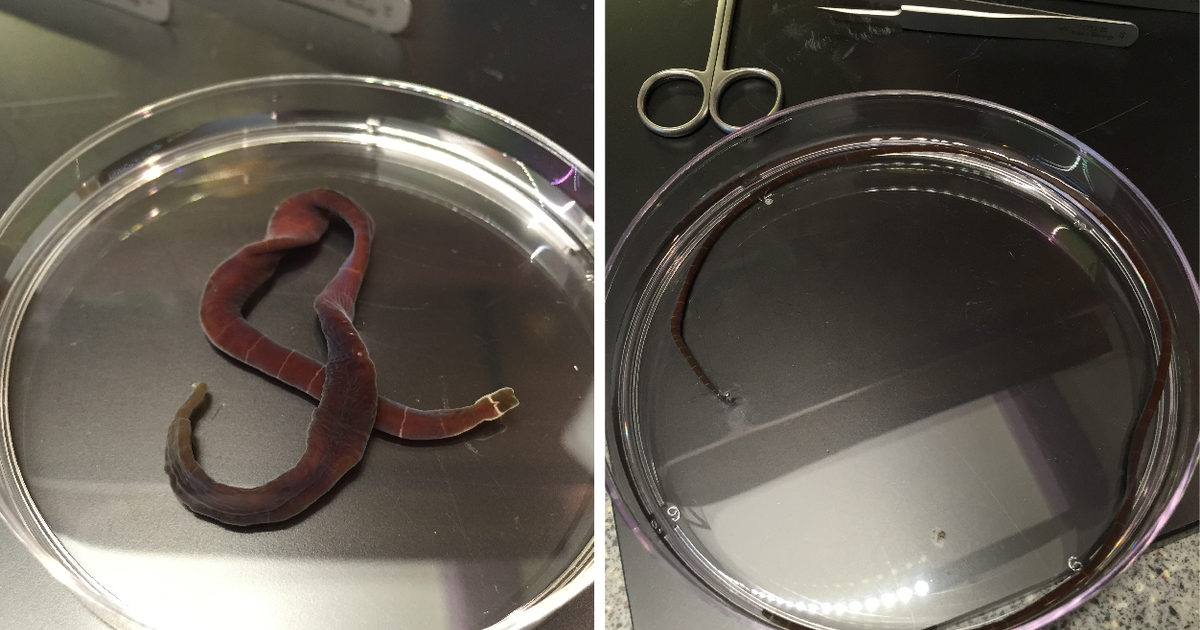

A nemertean worm.

Photo: Okinawa Institute of Science

Nemerteans are a group of about 1300 species in the Phylum Nemertea and are often called ribbon or proboscis worms. They do possess a proboscis used to capture prey. Most are marine and live on the bottom both near the beach and a great depth. They are more temperate than tropical and do have a few parasitic forms.

Adult Nemertea Worms – Terra C. Hiebert, PhD, Oregon University

In appearance they resemble flatworms but are larger and more elongated. Most are less than 20cm (8in) but some species along the Atlantic coast can reach 2m (7ft). The head end can be lobed or even spatula looking. Some species are pale in color and others quite colorful. Most nemerteans move over the substrate on a trail of slime produced by their skin. Some species can swim.

As mentioned, the proboscis is used to capture prey. It is a tube-like structure held in a sac near the head. When prey is detected, they can launch the proboscis out and over the victim. Sticky secretions help hold on to the prey while they ingest. Many species are armed with a stylet, dart, that is attached to the proboscis and is driven into the prey like a spear. From there toxins, secreted from the base of the proboscis are injected into the prey.

For many species the proboscis is connected to the digestive tract via a tube, there is no true mouth, but they do possess an anus. They are all carnivorous and feed on a variety of small living and dead invertebrates. Their menu includes annelid worms, mollusk, and crustaceans.

Nemerteans do possess a brain and most find their prey using chemoreception, though some species must literally bump into their prey to find it. They have multiple eyes that can detect light, and, like the true flatworms, they are negatively phototaxic. They are nocturnal by habitat and is probably why most of us have never seen one.

Many nemerteans, particularly the larger ones, have a habit of fragmenting when irritated, creating new worms. Most species have separate sexes and fertilization of the gametes is external (fertilization occurs in the environment).

Nemerteans are an interesting group of semi-large, sometimes toxic, hunters who prowl through the marine waters at night hunting prey. Seen by few, maybe one evening, while exploring or floundering, you may see one.

In Part 3 we will begin to explore a group of worms that are more round than flat. The Gastrotrichs.

Reference

Barnes, R.D. (1980). Invertebrate Zoology. Saunders Publishing. Philadelphia PA. pp. 1089.

by Rick O'Connor | Aug 10, 2024

I was recently conducting a survey for diamondback terrapins from my paddleboard in a small estuarine lagoon within the Pensacola Bay System. Even if we do not find our target species during these surveys – I, and our volunteers, see all sorts of other cool wildlife. On this trip I was treated to nesting osprey, a kingfisher, large blue crabs, and even a swimming eel. But one neat encounter was the numerous stingrays.

The Atlantic Stingray is one of the common members of the ray group who does possess a venomous spine.

Photo: Florida Museum of Natural History

They were lying in the sand and grassbeds, lots of them, and they all seemed to be of one species – the Atlantic stingray. My brain immediately went to “breeding season”, but when I checked the literature, I found that it was not breeding season, but pupping season – the babies were being born.

Atlantic Stingray (Dasyatis sabina) are true stingrays in the family Dasyatidae. This means they do possess the replaceable serrated venomous barb that makes these animals so famous. They are one of the smaller members of this family. Females can reach a disk width of two feet while the smaller males will only reach about one foot. Atlantic stingrays are a warm water species, migrating if they need to find suitable temperatures. They have been found in water as deep as 80 feet but are more common in the warmer shallower waters near shore. They are very common in our estuaries and being euryhaline (they tolerate a large range of salinity), are found in freshwater systems. There is a population that lives in the St. Johns River. Atlantic stingrays feed on a variety of benthic invertebrates and have special cells in the nose to detect the weak electric fields their prey give off while buried in the sediment. They also like to bury in the sand to ambush prey as they move by.

Breeding occurs in the fall. The smaller males possess two modified fins called claspers connected to their anal fins that are used to transfer sperm to the female. The males have modified teeth they can use to bite the fins of the females. They do this to hold on and make sperm transfer more successful.

The females do not begin to ovulate until spring. So, though they receive the sperm in the fall, fertilization does not occur until the spring. Instead of laying eggs, as some rays and skates do, baby Atlantic stingrays develop within the mother. This is not the same as mammals, who produce a placental to feed the developing young, but more like an internal egg with no hard shell. The embryo is attached to, and feeds from, a yolk sac. Gestation takes about 60 days at which time the yolk sac is depleted, and the young must emerge. Birth usually occurs in late July and early August, and each female will produce 1-4 small pups whose disk are about 10cm (4in.) wide. It was this birthing/pupping period I witnessed.

I returned the following day to search for terrapins and the number of stingrays was significantly fewer. It may be that the birthing process is fast, and the adults leave the coves afterwards. It may have been because that day was the day Hurricane Debby was making landfall east of us and the water levels were abnormally high – something the rays may have noticed and decided to leave – I am not sure.

I was really hoping to see the young rays swimming around – I did not – but plan to search again soon. Stingrays make many people nervous. I witnessed several adult rays whose tails had been cut off – which is very unfortunate – but they are actually cool creatures and fun to watch while paddleboarding. Maybe I will see a baby soon.

References

Dasyatis sabina. 2023. Florida Museum of Natural History. https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/species-profiles/dasyatis-sabina/.

Johnson, M.R., Snelson Jr., F.F. 1996. Reproductive Life History of the Atlantic Stingray, Dasyatis sabina (Pisces, Dasyatidae), in Freshwater St. Johns River, Florida. Bulletin of Marine Science, 59(1): 74-88.