by Ray Bodrey | Apr 20, 2021

Scott Jackson, UF/IFAS Extension Bay County & Florida Sea Grant

Ray Bodrey, UF/IFAS Extension Gulf County & Florida Sea Grant

Erik Lovestrand, UF/IFAS Extension Franklin County & Florida Sea Grant

Can you remember where you were one year ago last April? The uncertainty of each day seemed to go on forever. At this time last year, we were planning several education programs that eventually had to be canceled or migrated to online events. Scallop Sitters was one of our cooperative volunteer programs with Florida Fish and Wildlife (FWC) that was postponed during the pandemic in 2020. Thankfully, FWC biologists continued restoration work last year in the region with good results and steps forward. However, there was something painfully absent in these efforts – you!

One of the lessons last year taught us, is to appreciate our opportunities – whether it is to be with your family, friends, or serve your community freely through volunteer service. Some new service opportunities appeared while others were placed on hold. Thankfully, we are excited to announce the Scallop Sitters Citizen Scientist Restoration Program is returning to our area in St. Andrew, St. Joe, and Apalachicola Bays this summer!

Historically, populations of bay scallops were in large numbers and able to support fisheries across many North Florida bays, including St Andrew Bay. Consecutive years of poor environmental conditions, habitat loss, and general “bad luck” resulted in poor annual scallop production and caused the scallop fishery to close. Bay scallops are a short-lived species growing from babies to spawning adults and dying in about a year. Populations can recover quickly when growing conditions are good and can be decimated when conditions are bad.

An opportunity to jump start restoration of North Florida’s bay scallops came in 2011. Using funding as a result of the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill, a multi-county scallop restoration program was proposed and eventually established in 2016. Scientists with FWC use hatchery reared scallops obtained from parents or broodstock from local bays to grow them in mass to help increase the number of spawning adults near critical seagrass habitat.

FWC also created another program where volunteers can help with restoration called “Scallop Sitters” in 2018 and invited UF/IFAS Extension to help manage the volunteer portion of the program in 2019 which led to targeted efforts in Gulf and Bay Counties.

After a year’s hiatus, UF/IFAS Extension is partnering with FWC again in Bay and Gulf Counties and expanding the program into Franklin County. Despite initial challenges with rainfall, stormwater runoff, and low salinity, our Scallop Sitter volunteers have provided valuable information to researchers and restoration efforts, especially in these beginning years of the program.

Volunteers manage predator exclusion cages of scallops, which are either placed in the bay or by a dock. The cages provide a safe environment for the scallops to live and reproduce, and in turn repopulate the bays. Volunteers make monthly visits from June until January to their assigned cages where they clean scallops removing attached barnacles and other potential problem organisms. Scallop Sitters monitor the mortality rate and collect salinity data which determines restoration goals and success in targeted areas.

You are invited! Become a Scallop Sitter

1.Register on Eventbrite

2.Take the Pre-Survey (link will be sent to your email address upon Eventbrite Registration)

3.View a Virtual Workshop in May

4.Attend a Zoom virtual Q & A session in May or June with multiple dates / times available

5.Pick up supplies & scallops on June 17 with an alternate pick-up date to be announced

UF/IFAS Extension is an Equal Opportunity Institution.

by Erik Lovestrand | Mar 11, 2021

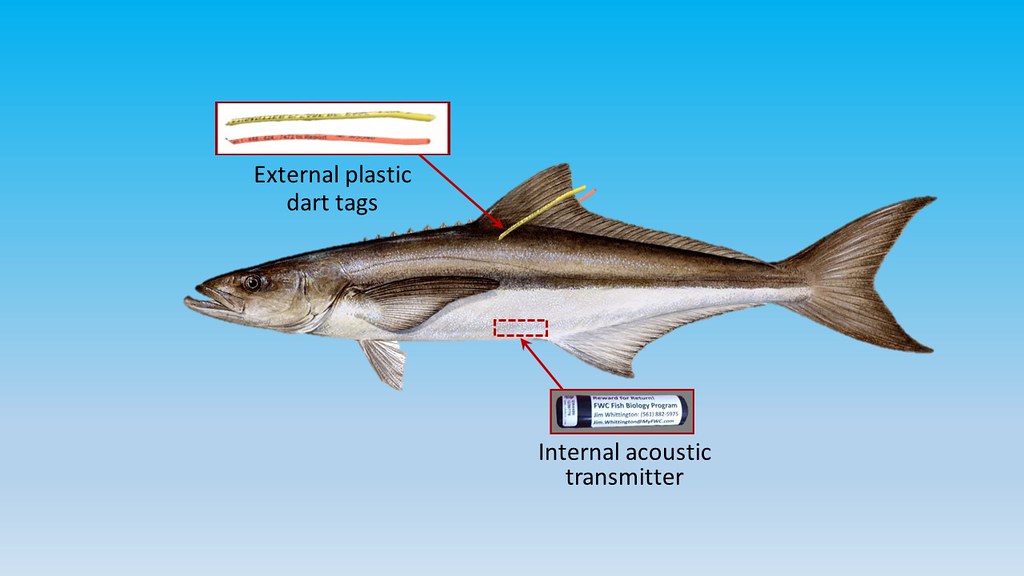

Cobia Researchers use Transmitters as well as Tags to Gather Data on Migratory Patterns

I must admit to having very limited personal experience with Cobia, having caught one sub-legal fish to-date. However, that does not diminish my fascination with the fish, particularly since I ran across a 2019 report from the Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission titled “Management Profile for Gulf of Mexico Cobia.” This 182-page report is definitely not a quick read and I have thus far only scratched the surface by digging into a few chapters that caught my interest. Nevertheless, it is so full of detailed life history, biology and everything else “Cobia” that it is definitely worth a look. This posting will highlight some of the fascinating aspects of Cobia and why the species is so highly prized by so many people.

Cobia (Rachycentron canadum) are the sole species in the fish family Rachycentridae. They occur worldwide in most tropical and subtropical oceans but in Florida waters, we actually have two different groups. The Atlantic stock ranges along the Eastern U.S. from Florida to New York and the Gulf stock ranges From Florida to Texas. The Florida Keys appear to be a mixing zone of sorts where Cobia from both stocks go in the winter. As waters warm in the spring, these fish head northward up the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of Florida. The Northern Gulf coast is especially important as a spawning ground for the Gulf stock. There may even be some sub-populations within the Gulf stock, as tagged fish from the Texas coast were rarely caught going eastward. There also appears to be a group that overwinters in the offshore waters of the Northern Gulf, not making the annual trip to the Keys. My brief summary here regarding seasonal movement is most assuredly an over-simplification and scientists agree more recapture data is needed to understand various Cobia stock movements and boundaries.

Worldwide, the practice of Cobia aquaculture has exploded since the early 2000’s, with China taking the lead on production. Most operations complete their grow-out to market size in ponds or pens in nearshore waters. Due to their incredible growth rate, Cobia are an exceptional candidate for aquaculture. In the wild, fish can reach weights of 17 pounds and lengths of 23 inches in their first year. Aquaculture-raised fish tend to be shorter but heavier, comparatively. The U.S. is currently exploring rules for offshore aquaculture practices and cobia is a prime candidate for establishing this industry domestically.

Spawning takes place in the Northern Gulf from April through September. Male Cobia will reach sexual maturity at an amazing 1-2 years and females within 2-3 years. At maturity, they are able to spawn every 4-6 days throughout the spawning season. This prolific nature supports an average annual commercial harvest in the Gulf and East Florida of around 160,000 pounds. This is dwarfed by the recreational fishery, with 500,000 to 1,000,000 pounds harvested annually from the same region.

One of the Cobia’s unique features is that they are strongly attracted to structure, even if it is mobile. They are known to shadow large rays, sharks, whales, tarpon, and even sea turtles. This habit also makes them vulnerable to being caught around human-made FADs (Fish Aggregating Devices). Most large Cobia tournaments have banned the use of FADs during their events to recapture a more sporting aspect of Cobia fishing.

To wrap this up I’ll briefly recount an exciting, non-fish-catching, Cobia experience. My son and I were in about 35 feet of water off the Wakulla County coastline fishing near an old wreck. Nothing much was happening when I noticed a short fin breaking the water briefly, about 20 yards behind a bobber we had cast out with a dead pinfish under it. I had not seen this before and was unaware of what was about to happen. When the fish ate that bait and came tight on the line the rod luckily hung up on something in the bottom of the boat. As the reel’s drag system screamed, a Cobia that I gauged to be 4-5 feet long jumped clear out of the water about 40 yards from us. Needless to say, by the time we gained control of the rod it was too late; a heartbreaking missed opportunity. Every time we have been fishing since then, I just can’t stop looking for that short, pointed fin slicing towards one of our baits.

by Rick O'Connor | Apr 18, 2019

Oysters are like snakes… you either like them or you hate them. You rarely hear someone say – “yea, their okay”. It’s either I can’t get enough of them, or they are the most disgusting thing in the sea.

Courtesy of Florida Sea Grant

That said, they are part of our culture. Growing up here in the Florida panhandle, there were oyster houses everywhere. They are as common on menus as French fries or coleslaw. Some like them raw, some like them in gumbo or stews, others are fried oyster fans. But whether you eat them or not, you are aware of them. They are part of being in the northern Gulf of Mexico.

In recent decades the historic oyster beds that supported so many families over the years have declined in production. There are a variety of stressors triggering this. Increased sedimentation, decreased salinity, overharvesting, not returning old shell to produce new reefs, and many more. The capitol of northwest Florida’s oyster coast is Apalachicola. Many are aware of the decline of harvest there. Certainly, impacted by the “water wars” between our state and Georgia, there are other reasons why this fishery has declined. I had a recent conversation with a local in Apalachicola who mentioned they had one of their worst harvest on record this past year. Things are really bad there.

An oysterman uses his 11 foot long tongs to collect oysters from the bottom of Apalachicola Bay

Photo: Sea Grant

Despite the loss of oysters and oyster habitat, there has not been a decline in the demand for them at local restaurants. There have been efforts by Florida Sea Grant and others to help restore the historic beds, improve water quality, and assist some with the culture of oysters in the panhandle.

Enter the Bream Fisherman’s Association of Pensacola.

This group has been together for a long time and have worked hard to educate and monitor our local waterways. In 2018 they worked with a local oyster grower and the University of West Florida’s Center for Environmental Diagnostics and Bioremediation to develop an oyster garden project called Project Oyster Pensacola. Volunteers were recruited to purchase needed supplies and grow young oysters in cages hanging from their docks. Participants lived on Perdido, Blackwater, East, and Escambia Bays. Bayous Texar, and Grande. As well as Big Lagoon and Santa Rosa Sound. The small, young oysters (spat) were provided by the Pensacola Bay Oyster Company. The volunteers would measure spat growth over an eight-month period beginning in the spring of 2018. In addition, they collected data on temperature, salinity, and dissolved oxygen at their location.

After the first year, the data suggests where the salinity was higher, the oysters grew better. Actually, low salinity proved to be lethal to many of them. This is a bit concerning when considering the increase rainfall our community has witnessed over the last two years. Despite an interest in doing so, the volunteers were not allowed to keep their oysters for consumption. Permits required that the oysters be placed on permitted living shoreline projects throughout the Pensacola Bay area.

Oyster bags used in a bulkhead restoration project.

Photo: Florida Department of Environmental Protection

We all know how important oysters are to the commercial seafood industry, but it turns out they are as important to the overall health to the bays ecology. A single oyster has been reported to filter as much as 50 gallons of seawater an hour. This removes sediments and provides improved water clarity for the growth of seagrasses. It has been estimated that seagrasses are vital to at least 80% of the commercially important seafood species. It is well known that seagrasses and salt marshes are full of life. However, studies show that biodiversity and biological production are actually higher in oyster reefs. Again, supporting a booming local recreational fishing industry.

This project proved to be very interesting in it’s first year. BFA will be publishing a final report soon and plan to do a second round. For the oyster lovers in the area, increasing local oysters would be nothing short of wonderful.

by Rick O'Connor | Jun 8, 2018

We have been posting articles discussing some of the issues our estuaries are facing; this post will focus on one of the things you can do to help reduce the problem – a Florida Friendly Yard.

Florida Friendly Landscaping saves money and reduces our impact on the estuarine environment.

Photo: UF IFAS

The University of Florida IFAS developed the Florida Friendly Landscaping Program. It was developed to be included in the Florida Yards & Neighborhoods (FYN) program, HomeOwner and FYN Builder and Developer programs, and the Florida-Friendly Best Management Practices for Protection of Water Resources by the Green Industries (GI-BMP) Program in 2008.

A Florida Friendly Yard is based on nine principals that can both reduce your impact on local water quality but also save you money. Those nine principals are:

- Right Plant, Right Place – We recommend that you use native plants in the right location whenever possible. Native plants require little fertilizer, water, or pesticides to maintain them. This not only reduces the chance of these chemicals entering our waterways but also saves you money. The first step in this process is to have your soil tested at your local extension office. Once your soil chemistry is known, extension agents can do a better job recommending native plants for you.

- Water Efficiently – Many homeowners in the Florida panhandle have irrigation systems on timers. This makes sense from a management point of view but can lead to unnecessary runoff and higher water bills. We have all seen sprinkler systems operating during rain events – watering at that time certainly is not needed. FFY recommends you water only when your plants show signs of wilting, water during the cooler times of day to reduce evaporation of your resource, and check system for leaks periodically. Again, this helps our estuaries and saves you money.

- Fertilize Appropriately – No doubt, plants need fertilizer. Water, sunlight, and carbon dioxide produce the needed energy for plants to grow, but it does not provide all of the nutrients needed to create new cells – fertilizers provide needed those nutrients. However, plants – like all creatures – can only consume so much before the remainder is waste. This is the case with fertilizers. Fertilizer that is not taken up by the plant will wash away and eventually end up in a local waterway where it can contribute to eutrophication, hypoxia, and possible fish kills. Apply fertilizers according to UF/IFAS recommendations. Never fertilize before a heavy rain.

- Mulch – In a natural setting, leaf litter remains on the forest floor. The environment and microbes, recycling needed nutrients within the system, break down these leaves. They also reduce the evaporation of needed moisture in the soil. FFY recommends a 2-3” layer of mulch in your landscape.

- Attract Wildlife – Native plants provide habitat for a variety of local wildlife. Birds, butterflies, and other creatures benefit from a Florida Friendly Yard. Choose plants with fruits and berries to attract birds and pollinators. This not only helps maintain their populations but you will find enjoyment watching them in your yard.

- Manage Yard Pests Responsibly – This is a toughie. Once you have invested in your yard, you do not want insect, or fungal, pests to consume it. There is a program called the Integrated Pest Management Program (IPM) that is recommended to help protect your lawn. The flow of the program basically begins with the least toxic form of pest management and moves down the line. Hopefully, there will not be a need for strong toxic chemicals. Your local county extension office can assist you with implementing an IPM program.

- Recycle – Return valuable nutrients to the soil and reduce waste that can enter our waterways by composting your turfgrass clippings, raked leaves, and pruned plants.

- Reduce Stormwater Runoff – ‘All drains lead to the sea’ – this line from Finding Nemo is, for the most part, true. Any water leaving your property will most likely end in a local waterway, and eventually the estuary. Rain barrels can be connected to rain gutters to collect rainwater. This water can be used for irrigating your landscape. I know of one family who used it to wash their clothes. Rain barrels must be maintained properly to not produce swarms of mosquitos, and your local extension office can provide you tips on how to do this. More costly and labor intensive, but can actually enhance your yard, are rain gardens. Modifying your landscape so that the rainwater flows into low areas where water tolerant plants grow not only reduces runoff but also provides a chance to grow beautiful plants and enhance some local wildlife.

- Protect the Waterfront – For those who live on a waterway, a living shoreline is a great way to reduce your impact on poor water quality. Living shorelines reduce erosion, remove pollutants, and enhance fisheries – all good. A living shoreline is basically restoring your shoreline to a natural vegetative state. You can design this so that you still have water access but at the same time help reduce storm water runoff issues. Planting below the mean high tide line will require a permit from the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, since the state owns that land, and it could require a breakwater just offshore to help protect those plants while they are becoming established. If you have questions about what type of living shoreline you need, and how to navigate the permit process, contact your local county extension office.

Santa Rosa Sound

Photo: Dr. Matt Deitch

These nine principals of a Florida Friendly Yard, if used, will go a long way in reducing our communities’ impact on the water and soil quality in our local waterways. Read more at http://fyn.ifas.ufl.edu/about.htm.

by Rick O'Connor | Jul 29, 2017

ARTICLE BY DR. MATT DEITCH; water quality specialist – University of Florida Milton

Summer is a great time for weather-watching in the Florida panhandle. Powerful thunderstorms appear out of nowhere, and can pour inches of rain in an area in a single afternoon. Our bridges, bluffs, and coastline allow us to watch them develop from a distance. Yet as they come closer, it is important to recognize the potential danger they pose—lightning from these storms can strike anywhere nearby, and can cause fatality for a person who is struck. Nine people were killed by lightning strike in Florida in 2016 alone, more than in any other state. Because of the risk posed by lightning, my family and I enjoy these storms up-close from indoors.

Carpenter’s Creek in Pensacola

Photo: Dr. Matt Deitch

A fraction of the rain that falls during these storms is delivered to our bays, bayous, and estuaries through a drainage network of creeks and rivers. This streamflow serves several important ecological functions, including preventing vegetation encroachment and maintaining habitat features for fish and amphibians through scouring the streambed. High flows also deposit fine sediment on the floodplain, helping to replenish nutrients to floodplain soil. On average, only about one-third of the water that falls as rain (on average, more than 60 inches per year!) turns into streamflow. The rest may either infiltrate soil and percolate into groundwater; or be consumed and transpired by plants; or evaporate off vegetation, from the soil, or the ground surface before reaching the soil. Evaporation and transpiration play an especially large role in the water cycle during summer: on average, most of the rain that falls in the Panhandle occurs during summer, but most stream discharge occurs during winter.

The water that flows in streams carries with it many substances that accumulate in the landscape. These substances—which include pollutants we commonly think of, such as excessive nutrients comprised of nitrogen and phosphorus, as well as silt, oil, grease, bacteria, and trash—are especially abundant when streamflow is high, typically during and following storm events. Oil, grease, bacteria, and trash are especially common in urban areas. The United States EPA and Florida Department of Environmental Protection have listed parts of the Choctawhatchee, St. Andrew, Perdido, and Pensacola Bays as impaired for nutrients and coliform bacteria. Pollution issues are not exclusive to the Panhandle: some states (such as Maryland and California) have even developed regulatory guidelines in streams (TMDLs) for trash!

Many local and grassroots organizations are taking the lead on efforts to reduce pollution. Some municipalities have recently publicized efforts to enforce laws on picking up pet waste, which is considered a potential source of coliform bacteria in some places. Some conservation groups in the panhandle organize stream debris pick-up days from local streams, and others organize volunteer citizens to monitor water quality in streams and the bays where they discharge. Together, these efforts can help to keep track of pollution levels, demonstrate whether restoration efforts have improved water quality, and maintain healthy beaches and waterways we rely on and value in the Florida Panhandle.

Santa Rosa Sound

Photo: Dr. Matt Deitch

by Laura Tiu | Jun 3, 2017

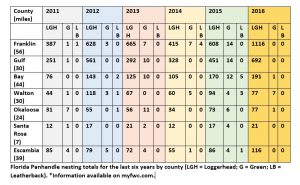

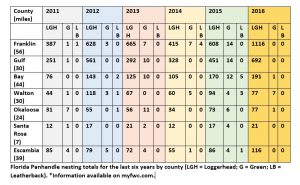

There are five species of sea turtles that nest from May through October on Florida beaches. The loggerhead, the green turtle and the leatherback all nest regularly in the Panhandle, with the loggerhead being the most frequent visitor. Two other species, the hawksbill and Kemp’s Ridley nest infrequently. All five species are listed as either threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act.

Due to their threatened and endangered status, the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission/Fish and Wildlife Research Institute monitors sea turtle nesting activity on an annual basis. They conduct surveys using a network of permit holders specially trained to collect this type of information. Managers then use the results to identify important nesting sites, provide enhanced protection and minimize the impacts of human activities.

Statewide, approximately 215 beaches are surveyed annually, representing about 825 miles. From 2011 to 2015, an average of 106,625 sea turtle nests (all species combined) were recorded annually on these monitored beaches. This is not a true reflection of all of the sea turtle nests each year in Florida, as it doesn’t cover every beach, but it gives a good indication of nesting trends and distribution of species.

If you want to see a sea turtle in the Florida Panhandle, please visit one of the state-permitted captive sea turtle facilities listed below, admission fees may be charged. Please call the number listed for more information.

If you want to see a sea turtle in the Florida Panhandle, please visit one of the state-permitted captive sea turtle facilities listed below, admission fees may be charged. Please call the number listed for more information.

- Gulf Specimen Marine Laboratory, 222 Clark Dr, Panacea, FL 32346 850-984-5297 Admission Fee

- Gulf World Marine Park, 15412 Front Beach Rd, Panama City, FL 32413 850-234-5271 Admission Fee

- Gulfarium Marine Adventure Park, 1010 Miracle Strip Parkway SE, Fort Walton Beach, FL 32548 850-243-9046 or 800-247-8575 Admission Fee

- Navarre Beach Sea Turtle Center, 8740 Gulf Blvd, Navarre, FL 32566 850-499-6774

To watch a female loggerhead turtle nest on the beach, please join a permitted public turtle watch. During sea turtle nesting season, The Emerald Coast CVB/Okaloosa County Tourist Development Council offers Nighttime Educational Beach Walks. The walks are part of an effort to protect the sea turtle populations along the Emerald Coast, increase ecotourism in the area and provide additional family-friendly activities. For more information or to sign up, please email ECTurtleWatch@gmail.com. An event page may also be found on the Emerald Coast CVB’s Facebook page: facebook.com/FloridasEmeraldCoast.