by Sheila Dunning | Nov 9, 2018

As the trees begin to turn various shades of red, many people begin to inquire about the Popcorn trees. While their autumn coloration is one of the reasons they were introduced to the Florida environment, it took years for us to realize what a menace Popcorn trees have become. Triadica sebifera, the Chinese tallowtree or Popcorn tree, was introduced to Charleston, South Carolina in the late 1700s for oil production and use in making candles, earning it another common name, the Candleberry tree. Since then, it has spread to every coastal state from North Carolina to Texas, and inland to Arkansas. In Florida it occurs as far south as Tampa. It is most likely to spread to wildlands adjacent to or downstream from areas landscaped with Triadica sebifera, displacing other native plant species in those habitats. Therefore, Chinese tallowtree was listed as a noxious weed by the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services Noxious Weed List (5b-57.007 FAC) in 1998, which means that possession with the intent to sell, transport, or plant is illegal in the state of Florida. The common name of Florida Aspen is sometimes used to market Popcorn tree in mail-order ads. Remember it’s still the same plant.

As the trees begin to turn various shades of red, many people begin to inquire about the Popcorn trees. While their autumn coloration is one of the reasons they were introduced to the Florida environment, it took years for us to realize what a menace Popcorn trees have become. Triadica sebifera, the Chinese tallowtree or Popcorn tree, was introduced to Charleston, South Carolina in the late 1700s for oil production and use in making candles, earning it another common name, the Candleberry tree. Since then, it has spread to every coastal state from North Carolina to Texas, and inland to Arkansas. In Florida it occurs as far south as Tampa. It is most likely to spread to wildlands adjacent to or downstream from areas landscaped with Triadica sebifera, displacing other native plant species in those habitats. Therefore, Chinese tallowtree was listed as a noxious weed by the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services Noxious Weed List (5b-57.007 FAC) in 1998, which means that possession with the intent to sell, transport, or plant is illegal in the state of Florida. The common name of Florida Aspen is sometimes used to market Popcorn tree in mail-order ads. Remember it’s still the same plant.

Although Florida is not known for the brilliant fall color enjoyed by other northern and western states, we do have a number of trees that provide some fall color for our North Florida landscapes. Red maple, Acer rubrum, provides brilliant red, orange and sometimes yellow leaves. The native Florida maple, Acer floridum, displays a combination of bright yellow and orange color during fall. And there are many Trident and Japanese maples that provide striking fall color. Another excellent native tree is Blackgum, Nyssa sylvatica. This tree is a little slow in its growth rate but can eventually grow to seventy-five feet in height. It provides the earliest show of red to deep purple fall foliage. Others include Persimmon, Diospyros virginiana, Sumac, Rhus spp. and Sweetgum, Liquidambar styraciflua. In cultivated trees that pose no threat to native ecosystems, Crape myrtle, Lagerstroemia spp. offers varying degrees of orange, red and yellow in its leaves before they fall. There are many cultivars – some that grow several feet to others that reach nearly thirty feet in height. Also, Chinese pistache, Pistacia chinensis, can deliver a brilliant orange display.

Young Trident maple with fall foliage. Photo credit: Larry Williams

There are a number of dependable oaks for fall color, too. Shumardi, Southern Red and Turkey are a few to consider. These oaks have dark green deeply lobed leaves during summer turning vivid red to orange in fall. Turkey oak holds onto its leaves all winter as they turn to brown and are pushed off by new spring growth. Our native Yellow poplar, Liriodendron tulipifera, and hickories, Carya spp., provide bright yellow fall foliage. And it’s difficult to find a more crisp yellow than fallen Ginkgo, Ginkgo biloba, leaves. These trees represent just a few choices for fall color. Including one or several of these trees in your landscape, rather than allowing the Popcorn trees to grow, will enhance the season while protecting the ecosystem from invasive plant pests.

For more information on Chinese tallowtree, removal techniques and native alternative trees go to: http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/ag148.

by Sheila Dunning | Apr 14, 2018

Having just completed the Okaloosa/Walton Uplands Master Naturalist course, I would like to share information from the project that was presented by Ann Foley.

The Florida Torreya. Photo provided by Shelia Dunning

The Florida Torreya is the most endangered tree in North America, and perhaps the world! Less than 1% of the historical population survives. Unless something is done soon, it may disappear entirely! You can see them on public lands in Florida at Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve and beautiful Torreya State Park.

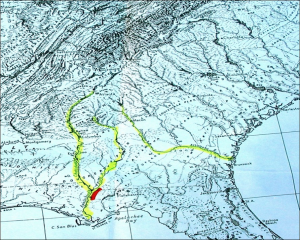

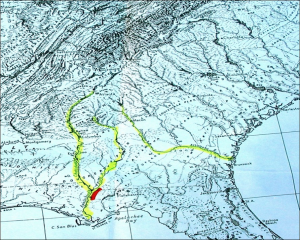

The Florida Torreya (Torreya taxifolia) is one of the oldest known tree species on earth; 160 million years old. It was originally an Appalachian Mountains ranged tree. As a result of our last “Ice Age” melt, retreating Icebergs pushed ground from the Northern Hemisphere, bringing the Florida Torreya and many other northern plant species with them.

The Florida Torreya was “left behind” in its current native pocket refuge, a short 40 mile stretch along the banks of the Apalachicola River. There were estimates of 600,000 to 1,000,000 of these trees in the 1800’s. Torreya State Park, named for this special tree, is currently home to about 600 of them. Barely thriving, this tree prefers a shady habitat with dark, moist, sandy loam of limestone origin which the park has to offer.

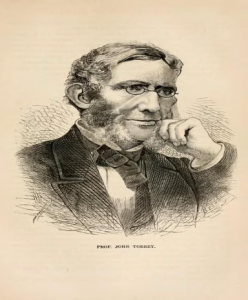

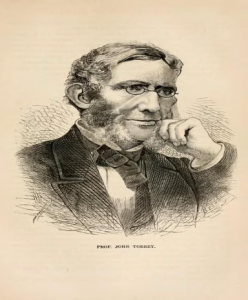

Hardy Bryan Croom, Botanist, discovered the tree in 1833, along the bluffs and ravines of Jackson, Liberty and Gadsen Counties, Florida and Decatur County in Georgia. He named it Florida Torreya (TOR-ee-uh), in honor of Dr. John Torrey, a renowned 18th century scientist.

Torreya trees are evergreen conifers, conically shaped, have whorled branches and stiff, sharp pointed, dark green needle-like leaves. Scientists noted the Torreya’s decline as far back as the 1950’s! Mature tree heights were once noted at 60 feet, but today’s trees are immature specimens of 3-6 feet, thought to be ‘root/stump sprouts.’

Known locally as “Stinking Cedar,” due to its strong smell when the leaves and cones are crushed, it was used for fence posts, cabinets, roof shingles, Christmas trees and riverboat fuel. Over-harvesting in the past and natural processes are taking a tremendous toll. Fungi are attacking weakened trees, causing the critically endangered species to die-off. Other declining factors include: drought, habitat loss, deer and loss of reproductive capability.

With federal and state protection, the Florida Torreya was listed as an endangered species in 1983. There is great concern for this ancient tree in scientific community and with citizen organizations. Efforts are underway to help bring this tree back from the edge of extinction!

Efforts include CRISPR gene editing technology research being done by the University of Florida Dept. of Forest Resources and Conservation- making the tree more resistant to disease. Torreya Guardians “rewilding and “assisted migration”. Reintroducing the tree to it’s former native range in the north near the Biltmore Estate in Asheville, NC, which has maintained a grove of Torreya trees and offspring since 1939 and supplying seeds for propagation from their healthy forest. Long before saving the earth became a global concern, Dr. Seuss (Theodor Seuss Geisel), spoke through his character the Lorax warning against urban progress and the danger it posed to the earth’s natural beauty. All of these groups, and many others, hope their efforts will collectively help bring this tree back from the brink!

by Carrie Stevenson | Jan 5, 2018

The ghost flower in full bloom. Photo credit: Carol Lord

Imagine you are enjoying perfect fall weather on a hike with your family, when suddenly you come upon a ghost. Translucent white, small and creeping out of the ground behind a tree, you stop and look closer to figure out what it is you’ve just seen. In such an environment, the “ghost” you might come across is the perennial wildflower known as the ghost plant (Monotropa uniflora, also known as Indian pipe). Maybe it’s not the same spirit from the creepy story during last night’s campfire, but it’s quite unexpected, nonetheless. The plant is an unusual shade of white because it does not photosynthesize like most plants, and therefore does not create cholorophyll needed for green leaves.

In deeply shaded forests, a thick layer of fallen leaves, dead branches, and even decaying animals forms a thick mulch around tree bases. This humus layer is warm and holds moisture, creating the perfect environment for mushrooms and other fungi to grow. Because there is very little sunlight filtering down to the forest floor, the ghost flower plant adapted to this shady, wet environment by parasitizing the fungi growing in the woods. Ghost plants and their close relatives are known as mycotrophs (myco: fungus, troph: feeding).

Ghost plant in bloom at Naval Live Oaks reservation in Gulf Breeze, Florida. Photo credit: Shelley W. Johnson

These plants were once called saprophytes (sapro: rotten, phyte: plant), with the assumption that they fed directly on decaying matter in the same way as fungi. They even look like mushrooms when emerging from the soil. However, research has shown the relationship is much more complex. While many trees have symbiotic relationships with fungi living among their root systems, the mycotrophs actually capitalize on that relationship, tapping into in the flow of carbon between trees and fungi and taking their nutrients.

Mycotrophs grow throughout the United States except in the southwest and Rockies, although they are a somewhat rare find. The ghost plant is mostly a translucent shade of white, but has some pale pink and black spots. The flower points down when it emerges (looking like its “pipe” nickname) but opens up and releases seed as it matures. They are usually found in a cluster of several blooms.

The next time you explore the forests around you, look down—you just might see a ghost!

by Carrie Stevenson | Jan 5, 2018

The swing hanging from our magnolia tree has provided many happy memories for our family. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson

Do you have a favorite tree? Often, the trees in our lives tell a story.

One of the selling points when we bought our house 14 years ago was the tall, healthy Southern magnolia in the front yard. It was beautiful, and I could see it out my front window. A perfect shade tree, I could envision a swing hanging from its branches one day. Within six months of moving into the house, Hurricane Ivan struck. A neighbor’s tree fell and sheared off a quarter of the branches from our beloved magnolia. We were lucky to have minimal damage otherwise, and hoped the tree would survive.

The branches and leaves eventually filled in, and we added that swing I had imagined. One day I was pushing my daughter in the swing, when a car slowed on our street and stopped at our mailbox. A man stepped out and asked, “Are you enjoying that tree?” I responded that we very much were, and with a smile, he explained that his family built our house and that he planted that very magnolia tree 40 years before, when his son was born. He was so happy to see us enjoying the tree that he could not help but stop.

I was so grateful to hear that story and know that our family’s favorite tree held such special meaning. Our enjoyment existed because of the joyous celebration of a new birth. That is why we plant trees. For the benefit of those yet unborn, to commemorate special moments, and to provide the very oxygen we breathe. As the Greek proverb goes, “Society grows great when old men plant trees whose shade they know they shall never sit in.”

January 19 is Florida’s Arbor Day, a time to celebrate the many benefits of trees, and the day is often celebrated by planting new trees. Winter is the best time of year to plant trees, as they are able to establish roots without competing with the energy needs of new branches and leaves that come along in springtime.

“The best time to plant a tree is twenty years ago. The second best time is now.” –Anonymous

Check with your local Extension offices, garden clubs, and municipalities to find out if there is an Arbor Day event near you! Several local agencies have joined forces to organize tree giveaway events in observance of Florida’s Arbor Day.

Escambia County:

Thursday, January 18:

Deadline for UF IFAS Extension/Escambia County’s second annual Arbor Day Mail Art Contest. To participate, mail a drawing, painting, or mixed media artwork with the theme, “Strong Trees, Strong Communities” to Arbor Day Art Contest c/o Escambia County Extension, 3740 Stefani Road, Cantonment, FL 32533. Please include your name, age, and contact information on the back of your artwork. Contest entries must arrive by mail or be dropped off by Jan. 18 and will be judged at the tree giveaway on Jan. 20 at Barrineau Park Community Center.

First place winners of the art contest will receive prizes including a seven-gallon tree, a shovel, and a tree book. Second place winners will receive a tree book and third place winners will receive gardening gloves. Categories include children (12-under), teen (13-18), and adult (over 18). All participants in attendance at the tree giveaway will receive a special edition Arbor Day water bottle featuring last year’s winning design.

Many communities plant trees to celebrate Arbor Day. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson

Saturday, January 20th

Escambia County will hold their tree giveaway and public planting from 10 a.m. to noon Saturday, Jan. 20 at Barrineau Park Community Center, located at 6055 Barrineau Park Road, Molino. Support for the event is provided by the Florida Forest Service, Resource Management Services, and Escambia County UF-IFAS Extension. Each attendee will receive two free native 1-gallon trees. Species available include tulip poplar, Chickasaw plum, Shumard oak, and fringetree.

For more information about either Escambia event, contact Carrie Stevenson, Coastal Sustainability Agent III, UF IFAS Extension, at 850-475-5230 or ctsteven@ufl.edu.

Santa Rosa County:

Friday, January 19

10 am—Navarre Garden Club Arbor Day celebration. Foresters will give away 1-gallon containerized trees and conduct a have tree planting demo. 7254 Navarre Parkway, Navarre, 32566. For more information, contact Mary Salinas, 850-623-3868 or maryd@santarosa.fl.gov

Saturday, January 20th

10 am—Milton Garden Club Arbor Day celebration. Foresters will give away 1-gallon containerized trees and conduct a have tree planting demo. 5256 Alabama Street, Milton. For more information, contact Mary Salinas, 850-623-3868 or maryd@santarosa.fl.gov

Leon County:

Saturday, January 20th

9am to 12pm – City of Tallahassee/Leon County Arbor Day Celebration – Join City and County Staff, UF/IFAS Leon County Extension Faculty and Master Gardener volunteers at the Apalachee Regional Park (7550 Apalachee Pkwy) for a tree planting in honor of Arbor Day. Citizens are invited to come help plant hundreds of trees in the park and also learn about the benefits of trees, how to properly plant a tree, and after the planting is done, take a tree identification walk. For more information, contact Mindy Mohrman, City/County Urban Forester at 850.891.6415 or melinda.mohrman@talgov.com

by Sheila Dunning | Dec 15, 2017

According to Druid lore, hanging the plant in homes would bring good luck and protection. Holly was considered sacred because it remained green and strong with brightly colored red berries no matter how harsh the winter. Most other plants would wilt and die.

Later, Christians adopted the holly tradition from Druid practices and developed symbolism to reflect Christian beliefs. Today, the red berries are said to represent the blood that Jesus shed on the cross when he was crucified. Additionally, the pointed leaves of the holly symbolize the crown of thorns Jesus wore on his head.

Later, Christians adopted the holly tradition from Druid practices and developed symbolism to reflect Christian beliefs. Today, the red berries are said to represent the blood that Jesus shed on the cross when he was crucified. Additionally, the pointed leaves of the holly symbolize the crown of thorns Jesus wore on his head.

Several hollies are native to Florida. Many more are cultivated varieties commonly used as landscape plants. Hollies (Ilex spp.) are generally low maintenance plants that come in a diversity of sizes, forms and textures, ranging from large trees to dwarf shrubs.

The berries provide a valuable winter food source for migratory birds. However, the berries only form on female plants. Hollies are dioecious plants, meaning male and female flowers are located on separate plants. Both male and female hollies produce small white blooms in the spring. Bees are the primary pollinators, carrying pollen from the male hollies 1.5 to 2 miles, so it is not necessary to have a male plant in the same landscape.

Several male hollies are grown for their compact formal shape and interesting new foliage color. Dwarf Yaupon Hollies (Ilex vomitoria ‘Shillings’ and ‘Bordeaux’) form symmetrical spheres without extensive pruning. ‘Bordeaux’ Yaupon has maroon-colored new growth. Neither cultivar has berries.

Hollies prefer to grow in partial shade but will do well in full sun if provided adequate irrigation. Most species prefer well-drained, slightly acidic soils. However, Dahoon holly (Ilex cassine) and Gallberry (Ilex glabra) naturally occurs in wetland areas and can be planted on wetter sites.

Evergreen trees retain leaves throughout the year and provide wind protection. The choice of one type of holly or another will largely depend on prevailing environmental conditions and windbreak purposes. If, for example, winds associated with storms or natural climatic variability occur in winter, then a larger leaved plant might be required.

The natives are likely to be better adapted to local climate, soil, pest and disease conditions and over a broader range of conditions. Nevertheless, non-natives may be desirable for many attributes such as height, growth rate and texture but should not reproduce and spread beyond the area planted or they may become problematic because of invasiveness.

There is increasing awareness of invasiveness, i.e., the potential for an introduced species to establish itself or become “naturalized” in an ecological community and even become a dominant plant that replaces native species. Tree and shrub species can become invasive if they aggressively proliferate beyond the windbreak. At first glance, Brazilian pepper (Schinus terebinthifolius), a fast-growing, non-native shrub that has a dense crown, might be considered an appropriate red berry producing species. However, it readily spreads seed disbursed by birds and has invaded many natural ecosystems. Therefore, the Florida Department of Environmental Protection has declared it illegal to plant this tree in Florida without a special permit. Consult the Florida Exotic Pest Plant Council’s Web page (www.fleppc.org) for a list of prohibited species in Florida.

For a more comprehensive list of holly varieties and their individual growth habits refer to ENH42 Hollies at a Glance: http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/mg021

by Carrie Stevenson | Nov 3, 2017

Red mangrove growing among black needlerush in Perdido Key. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Discovering something new is possibly the most exciting thing a field biologist can do. As students, budding biologists imagine coming across something no one else has ever noticed before, maybe even getting the opportunity to name a new bird, fish, or plant after themselves.

Well, here in Pensacola, we are discovering something that, while already named and common in other places, is extraordinarily rare for us. What we have found are red mangroves. Mangroves are small to medium-sized trees that grow in brackish coastal marshes. There are three common kinds of mangroves, black (Avicennia germinans), white (Laguncularia racemosa), and red (Rhizophora mangle).

Black mangroves are typically the northernmost dwelling species, as they can tolerate occasional freezes. They have maintained a large population in south Louisiana’s Chandeleur Islands for many years. White and red mangroves, however, typically thrive in climates that are warmer year-round—think of a latitude near Cedar Key and south. The unique prop roots of a red mangrove (often called a “walking tree”) jut out of the water, forming a thick mat of difficult-to-walk-through habitat for coastal fish, birds, and mammals. In tropical and semi-tropical locations, they form a highly productive ecosystem for estuarine fish and invertebrates, including sea urchins, oysters, mangrove and mud crabs, snapper, snook, and shrimp.

Interestingly, botanists and ecologists have been observing an expansion in range for all mangroves in the past few years. A study published 3 years ago (Cavanaugh, 2014) documented mangroves moving north along a stretch of coastline near St. Augustine. There, the mangrove population doubled between 1984-2011. The working theory behind this expansion (observed worldwide) is not necessarily warming average temperatures, but fewer hard freezes in the winter. The handful of red mangroves we have identified in the Perdido Key area have been living among the needlerush and cordgrass-dominated salt marsh quite happily for at least a full year.

Key deer thrive in mangrove forests in south Florida. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Two researchers from Dauphin Island Sea Lab are planning to expand a study published in 2014 to determine the extent of mangrove expansion in the northern Gulf Coast. After observing black mangroves growing on barrier islands in Mississippi and Alabama, we are working with them to start a citizen science initiative that may help locate more mangroves in the Florida panhandle.

So what does all of this mean? Are mangroves taking over our salt marshes? Where did they come from? Are they going to outcompete our salt marshes by shading them out, as they have elsewhere? Will this change the food web within the marshes? Will we start getting roseate spoonbills and frigate birds nesting in north Florida? Is this a fluke due to a single warm winter, and they will die off when we get a freeze below 25° F in January? These are the questions we, and our fellow ecologists, will be asking and researching. What we do know is that red mangrove propagules (seed pods) have been floating up to north Florida for many years, but never had the right conditions to take root and thrive. Mangroves are native, beneficial plants that stabilize and protect coastlines from storms and erosion and provide valuable food and habitat for wildlife. Only time will tell if they will become commonplace in our area.

If you are curious about mangroves or interested in volunteering as an observer for the upcoming study, please contact me at ctsteven@ufl.edu. We enjoy hearing from our readers.

As the trees begin to turn various shades of red, many people begin to inquire about the Popcorn trees. While their autumn coloration is one of the reasons they were introduced to the Florida environment, it took years for us to realize what a menace Popcorn trees have become. Triadica sebifera, the Chinese tallowtree or Popcorn tree, was introduced to Charleston, South Carolina in the late 1700s for oil production and use in making candles, earning it another common name, the Candleberry tree. Since then, it has spread to every coastal state from North Carolina to Texas, and inland to Arkansas. In Florida it occurs as far south as Tampa. It is most likely to spread to wildlands adjacent to or downstream from areas landscaped with Triadica sebifera, displacing other native plant species in those habitats. Therefore, Chinese tallowtree was listed as a noxious weed by the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services Noxious Weed List (5b-57.007 FAC) in 1998, which means that possession with the intent to sell, transport, or plant is illegal in the state of Florida. The common name of Florida Aspen is sometimes used to market Popcorn tree in mail-order ads. Remember it’s still the same plant.

As the trees begin to turn various shades of red, many people begin to inquire about the Popcorn trees. While their autumn coloration is one of the reasons they were introduced to the Florida environment, it took years for us to realize what a menace Popcorn trees have become. Triadica sebifera, the Chinese tallowtree or Popcorn tree, was introduced to Charleston, South Carolina in the late 1700s for oil production and use in making candles, earning it another common name, the Candleberry tree. Since then, it has spread to every coastal state from North Carolina to Texas, and inland to Arkansas. In Florida it occurs as far south as Tampa. It is most likely to spread to wildlands adjacent to or downstream from areas landscaped with Triadica sebifera, displacing other native plant species in those habitats. Therefore, Chinese tallowtree was listed as a noxious weed by the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services Noxious Weed List (5b-57.007 FAC) in 1998, which means that possession with the intent to sell, transport, or plant is illegal in the state of Florida. The common name of Florida Aspen is sometimes used to market Popcorn tree in mail-order ads. Remember it’s still the same plant.