by Rick O'Connor | Jan 19, 2018

In the last article, we discussed what phytoplankton are, what their needs were, and their importance to marine life throughout the Gulf and coastal estuaries. In this article, we will discuss the different types of phytoplankton found in our waters.

The spherical shape of the centric diatom.

Image: Florida International University

Marine scientists interested in the diversity and abundance of phytoplankton will typically sample using a plankton net. There are a variety of different shapes and sizes of these nets, but the basic design would be funnel shaped with a sample jar attached at the small end of the funnel. The plankton net would be towed behind the research vessel at varying depths for a set period of time. All plankton collected would be analyzed via a microscope. According to the text Identifying Marine Phytoplankton (1997) there are at least 14,000 species of phytoplankton and some suggest as many as 120,000. Most of these, 12,000-100,000, are diatoms, one of five classes of marine phytoplankton. The majority of the phytoplankton fall into one of two class, the diatoms and the dinoflagellates.

Diatoms are typically single celled algae encased in a clear silica shell called a frustule. The frustule can come in a variety of shapes, with or without spines, and many resemble snowflakes – their quite beautiful. They are found in the bay and Gulf in great numbers, as many as 40,000,000 cells / cup of seawater. They are the dominate phytoplankton in colder waters and are most abundant near upwellings. These are the “grasses of the sea” and the base of many marine food webs. When diatoms die, their silica shells sink to the seafloor forming layers of diatomaceous earth, which is used in filters for aquariums and oxygen mask in hospitals.

Dinoflagellates differ from diatoms in that they produce two flagella, small hair-like projections from the algae that are used for generating water currents and movement. Their shells are not silica but layers of membranes and are called thecas. Some membranes are empty and others contain different types of polysaccharides. Dinoflagellates are more abundant than diatoms in warmer waters. There are about 2000 species of them. One type, Noctiluca, are responsible for what locals call “phosphorus” or bioluminescence. These dinoflagellates produce a blue-ish light when disturbed. Many see this when walking the beach at night. Their footprints glow for a few seconds. At night, boaters can see this as their prop wash turns the dinoflagellates in the water column. The bioluminescence is more pronounced in the warm summer months and is believed to be defense against predation. The light is referred to as “cool” light in that the majority of the energy is used in producing light, not lost as heat as with typical incandescent bulbs – hence the birth of the LED light industry.

The dinoflagellate Karenia brevis.

Photo: Smithsonian Marine Station-Ft. Pierce FL

Several dinoflagellates produce toxins as a defense. Some generate what we call red tides. In the Gulf of Mexico, Karenia brevis is the species most responsible for red tide. Red tides typical form offshore and are blown into coastal areas via wind and currents. They are common off the coast of southwest Florida but occur occasionally in the panhandle. Many local red tides are actually formed in southwest Florida and pushed northward via currents. Red tides are known to kill marine mammals and fish, as well as closing areas for shellfish harvesting.

Like true plants, phytoplankton conduct photosynthesis. Between the diatoms and dinoflagellates, 50% of the planet’s oxygen is produced. These are truly important players in the ecology of both the open Gulf and local bays.

References

Annett, A.L., D.S. Carson, X. Crosta, A. Clarke, R.S. Ganeshram. 2010. Seasonal Progression of Diatom

Assemblages in Surface Waters of Ryder Bay, Antarctica. Polar Biology vol 33. Pp. 13-29.

Hasle, G.R., E.E. Syvertsen. 1997. Identifying Marine Phytoplankton. Academic Press Harcourt Brace and

Company. San Diego CA. edited by C.R. Tomas. Pp. 858.

Steidinger, K.A., K. Tangen. 1997. Identifying Marine Phytoplankton. Academic Press Harcourt Brace and

Company. San Diego CA. edited by C.R. Tomas. Pp. 858.

by Les Harrison | Jan 5, 2018

St. Marks River Preserve State Park is still being developed, but open for native habitat enthusiast and those who enjoy this environment as nature established it.

Located along the banks of the St. Marks River’s headwaters, this park offers an extensive system of trails for hiking, horseback riding, and off-road bicycling. The existing road network in the park takes visitors through upland pine forests, hardwood thickets and natural plant communities along the northern banks of the river.

The St. Marks River is not navigable within the park boundaries. It is not conducive to canoeing or kayaking unless visitors are willing to accept long portages through thick undergrowth.

Most of the trails are dry and sandy, but plan for the low water crossings which some of the trails traverse. The rainy months of summer increase the prospects of water crossings.

This preserve is home to a wide variety of native fauna including black bear, deer, turkey and much more. Wildlife tracks frequently crisscross the park’s roads and trails.

At the northern end of the park two sections have had timber removed. One plot has been replanted with wiregrass seed which should germinate this year. Both areas have been planted with long-leafed pine seedlings.

This preserve offers avian aficionados the opportunity to witness nature at its finest as birds fill the air with their calls. A wide assortment of residential and migratory birds can be viewed in their natural habitat.

There are currently no amenities available at the park and it does not have restroom facilities. Additionally, visitors must bring in water for themselves or their horse.

There are no fees presently required to enjoy this gem of a park. Located east of Tallahassee, it is 3.5 miles east of W.W. Kelly Road on Tram Rd (Leon County Highway 259) almost to the Jefferson County line.

Adequate planning should be made to pack in and pack out all needed items for the day. The nearest convenience stores are located in Wacissa a few miles west of the park on Tram Road.

by Carrie Stevenson | Jan 5, 2018

The ghost flower in full bloom. Photo credit: Carol Lord

Imagine you are enjoying perfect fall weather on a hike with your family, when suddenly you come upon a ghost. Translucent white, small and creeping out of the ground behind a tree, you stop and look closer to figure out what it is you’ve just seen. In such an environment, the “ghost” you might come across is the perennial wildflower known as the ghost plant (Monotropa uniflora, also known as Indian pipe). Maybe it’s not the same spirit from the creepy story during last night’s campfire, but it’s quite unexpected, nonetheless. The plant is an unusual shade of white because it does not photosynthesize like most plants, and therefore does not create cholorophyll needed for green leaves.

In deeply shaded forests, a thick layer of fallen leaves, dead branches, and even decaying animals forms a thick mulch around tree bases. This humus layer is warm and holds moisture, creating the perfect environment for mushrooms and other fungi to grow. Because there is very little sunlight filtering down to the forest floor, the ghost flower plant adapted to this shady, wet environment by parasitizing the fungi growing in the woods. Ghost plants and their close relatives are known as mycotrophs (myco: fungus, troph: feeding).

Ghost plant in bloom at Naval Live Oaks reservation in Gulf Breeze, Florida. Photo credit: Shelley W. Johnson

These plants were once called saprophytes (sapro: rotten, phyte: plant), with the assumption that they fed directly on decaying matter in the same way as fungi. They even look like mushrooms when emerging from the soil. However, research has shown the relationship is much more complex. While many trees have symbiotic relationships with fungi living among their root systems, the mycotrophs actually capitalize on that relationship, tapping into in the flow of carbon between trees and fungi and taking their nutrients.

Mycotrophs grow throughout the United States except in the southwest and Rockies, although they are a somewhat rare find. The ghost plant is mostly a translucent shade of white, but has some pale pink and black spots. The flower points down when it emerges (looking like its “pipe” nickname) but opens up and releases seed as it matures. They are usually found in a cluster of several blooms.

The next time you explore the forests around you, look down—you just might see a ghost!

by Rick O'Connor | Jan 5, 2018

Last year I began a series of articles on the Gulf of Mexico. They focused on the physical Gulf – water, currents, and the ocean floor. This year the articles will focus on the life within the Gulf, and there is a lot of it.

Single celled algae are the “grasses of the sea” and provide the base of most marine food chains.

Photo: University of New Hampshire

We will begin with the base of food web systems, the simplest creatures in the sea. The base of food systems are generally plants and the simplest of these are the single celled plants. Singled celled plants are a form of algae, not true plants in the sense we think of them, but serving the same role in the environment – which is the production of much needed energy.

What these single celled algae need to survive is the same as the more commonly known plants – sunlight, water, carbon dioxide, oxygen, and nutrients.

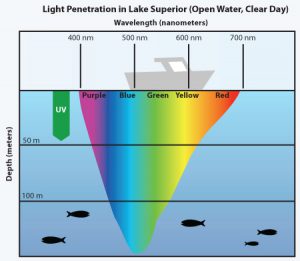

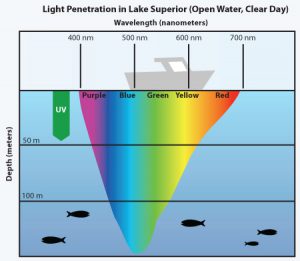

Sunlight is difficult for marine plants because sunlight only penetrates so deep. Therefore, marine plants and algae must live in shallow water, or have some mechanism to remain near the surface in the open sea. In relation to their overall body volume, smaller creatures have more surface area than larger ones. More surface area helps resist sinking and the smallest you can get is a single cell. Thus, most marine algae are single celled. Many single celled plants are encased in transparent shells that have spines and other adaptations to assist in increasing their surface area and keeping them near the surface. Some actually have drops of oil (buoyant in water) making it even easier to stay near the surface. These small floating algae drift in the surface currents, and drifting organisms are called plankton. Plankton that are “plant-like” are called phytoplankton.

The next needed resource is water; the Gulf and Bay are full of it. However, saltwater is not what they need – freshwater is, so they must desalinate the water before absorbing it. They can do this by adjusting the solutes within their cytoplasm. The greater the ratio of surface area is to volume, the more diffusion of solutes can take place – thus these small phytoplankton are very good at diffusing resources in (like water and carbon dioxide) and expelling waste (like ammonia and oxygen).

Image showing how deep different colors of light penetrates in the sea.

Image: Minnesota Sea Grant

Carbon dioxide and oxygen are dissolved in seawater and, like water, are diffused into the phytoplankton. Warmer water holds less oxygen so there would be a tendency to have more phytoplankton in colder waters. However, warmer waters are so because there is generally more sunlight, a needed resource. The colder, sunlit, surface waters off some coasts – such as California – have higher amounts of dissolved oxygen and are some of the most productive areas in the ocean. Phytoplankton can also serve as “carbon sinks” by removing carbon dioxide dissolved in the seawater coming from the atmosphere. However, this may not be the answer to excessive CO2 in the atmosphere because, like all creatures, you can only consume so much “food”. Excessive loads of carbon dioxide will not be consumed.

Finally, there is the need for nutrients. All plants need fertilizer. Nutrients in the sea come from either run-off from land, or decayed material from the ocean floor. Much of the nutrients are discharged into the Gulf by run-off from land. Because of this, much of the phytoplankton are congregated nearshore where rivers meet the sea. We think of marine life as equally distributed across the ocean, but in act it is not, there is more life nearshore. For the compost on the ocean floor to be of used by phytoplankton, it must reach the surface. This happens where a current called an upwelling occurs. Upwellings rise from the seafloor bringing with them the nutrients. Where upwellings occur, the seawater is colder, and sunlight abundant, you have the greatest concentration of marine life – all fueled by these phytoplankton.

In the Gulf, one of the most productive places is “the plume”, where the Mississippi River discharges. This massive river brings water, sediments, and nutrients, from most of the continent. The large plankton blooms attract massive schools of plankton consuming fish, predatory fish, sea birds, and marine mammals.

In the next post, we discuss some of the different phytoplankton that inhabit our coastal waters and the amazing things they do.

A satellite image showing the sediment plume of the Mississippi River. This plume brings with it nutrients that fuel plankton blooms.

Image: NASA satellite

References

Kirst G.O. (1996) Osmotic Adjustment in Phytoplankton and MacroAlgae. In: Kiene R.P., Visscher P.T.,

Keller M.D., Kirst G.O. (eds) Biological and Environmental Chemistry of DMSP and Related Sulfonium Compounds. Springer, Boston, MA

by Carrie Stevenson | Jan 5, 2018

The swing hanging from our magnolia tree has provided many happy memories for our family. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson

Do you have a favorite tree? Often, the trees in our lives tell a story.

One of the selling points when we bought our house 14 years ago was the tall, healthy Southern magnolia in the front yard. It was beautiful, and I could see it out my front window. A perfect shade tree, I could envision a swing hanging from its branches one day. Within six months of moving into the house, Hurricane Ivan struck. A neighbor’s tree fell and sheared off a quarter of the branches from our beloved magnolia. We were lucky to have minimal damage otherwise, and hoped the tree would survive.

The branches and leaves eventually filled in, and we added that swing I had imagined. One day I was pushing my daughter in the swing, when a car slowed on our street and stopped at our mailbox. A man stepped out and asked, “Are you enjoying that tree?” I responded that we very much were, and with a smile, he explained that his family built our house and that he planted that very magnolia tree 40 years before, when his son was born. He was so happy to see us enjoying the tree that he could not help but stop.

I was so grateful to hear that story and know that our family’s favorite tree held such special meaning. Our enjoyment existed because of the joyous celebration of a new birth. That is why we plant trees. For the benefit of those yet unborn, to commemorate special moments, and to provide the very oxygen we breathe. As the Greek proverb goes, “Society grows great when old men plant trees whose shade they know they shall never sit in.”

January 19 is Florida’s Arbor Day, a time to celebrate the many benefits of trees, and the day is often celebrated by planting new trees. Winter is the best time of year to plant trees, as they are able to establish roots without competing with the energy needs of new branches and leaves that come along in springtime.

“The best time to plant a tree is twenty years ago. The second best time is now.” –Anonymous

Check with your local Extension offices, garden clubs, and municipalities to find out if there is an Arbor Day event near you! Several local agencies have joined forces to organize tree giveaway events in observance of Florida’s Arbor Day.

Escambia County:

Thursday, January 18:

Deadline for UF IFAS Extension/Escambia County’s second annual Arbor Day Mail Art Contest. To participate, mail a drawing, painting, or mixed media artwork with the theme, “Strong Trees, Strong Communities” to Arbor Day Art Contest c/o Escambia County Extension, 3740 Stefani Road, Cantonment, FL 32533. Please include your name, age, and contact information on the back of your artwork. Contest entries must arrive by mail or be dropped off by Jan. 18 and will be judged at the tree giveaway on Jan. 20 at Barrineau Park Community Center.

First place winners of the art contest will receive prizes including a seven-gallon tree, a shovel, and a tree book. Second place winners will receive a tree book and third place winners will receive gardening gloves. Categories include children (12-under), teen (13-18), and adult (over 18). All participants in attendance at the tree giveaway will receive a special edition Arbor Day water bottle featuring last year’s winning design.

Many communities plant trees to celebrate Arbor Day. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson

Saturday, January 20th

Escambia County will hold their tree giveaway and public planting from 10 a.m. to noon Saturday, Jan. 20 at Barrineau Park Community Center, located at 6055 Barrineau Park Road, Molino. Support for the event is provided by the Florida Forest Service, Resource Management Services, and Escambia County UF-IFAS Extension. Each attendee will receive two free native 1-gallon trees. Species available include tulip poplar, Chickasaw plum, Shumard oak, and fringetree.

For more information about either Escambia event, contact Carrie Stevenson, Coastal Sustainability Agent III, UF IFAS Extension, at 850-475-5230 or ctsteven@ufl.edu.

Santa Rosa County:

Friday, January 19

10 am—Navarre Garden Club Arbor Day celebration. Foresters will give away 1-gallon containerized trees and conduct a have tree planting demo. 7254 Navarre Parkway, Navarre, 32566. For more information, contact Mary Salinas, 850-623-3868 or maryd@santarosa.fl.gov

Saturday, January 20th

10 am—Milton Garden Club Arbor Day celebration. Foresters will give away 1-gallon containerized trees and conduct a have tree planting demo. 5256 Alabama Street, Milton. For more information, contact Mary Salinas, 850-623-3868 or maryd@santarosa.fl.gov

Leon County:

Saturday, January 20th

9am to 12pm – City of Tallahassee/Leon County Arbor Day Celebration – Join City and County Staff, UF/IFAS Leon County Extension Faculty and Master Gardener volunteers at the Apalachee Regional Park (7550 Apalachee Pkwy) for a tree planting in honor of Arbor Day. Citizens are invited to come help plant hundreds of trees in the park and also learn about the benefits of trees, how to properly plant a tree, and after the planting is done, take a tree identification walk. For more information, contact Mindy Mohrman, City/County Urban Forester at 850.891.6415 or melinda.mohrman@talgov.com

by Rick O'Connor | Dec 15, 2017

2017 began as most years do, the Bermuda high slid east across the Atlantic Ocean and the cold fronts began to reach the Gulf Coast. However, this past winter was milder than normal. Either the high did not slide as far east as it typically does, or the fronts did not pack the punch they normally do – but we did not have as many deep freezes in 2017. That’s how it began.

The Bermuda High influences both our weather and climate in the Florida panhandle.

Image: Goddard Media NASA

As spring approached the Bermuda High made its’ annual move westward, bringing us the clockwise winds from the southeast and moisture from the Gulf. It was time for rain… and rain it did. It rained and rained and rained. It rained so much that the salinities in the local bayous in Pensacola, which typically run between 10-15 parts per thousands, were below 1 ppt – freshwater. These heavy rains triggered high bacteria counts in the water column, which triggered health advisories – increasing 139% this year.

Late spring and summer is the season of afternoon thunderstorms – and Sea Grants’ estuary monitoring programs in Pensacola Bay. This year we observed many things:

- Numerous bald eagles, more than we had seen before

- Communities calling about snake encounters – this is not unusual when it rains, but this year there were more venomous snakes than we typically see.

- We began to get calls concerning Cuban Anoles (an invasive lizard) all along the coast from Perdido Key to Gulf Breeze. As more people searched, more anoles were found. I saw the first two at my house this year.

- We were searching for horseshoe crabs, and found them! In several locations in the lower bay, but never found where they were nesting – we will continue to search in 2018.

- Our terrapin surveys extended to Walton County. We found two new terrapin nesting beaches in Escambia and the sea turtle nests reached record numbers across the state.

- Our scallop surveys in Santa Rosa Sound and Big Lagoon were a complete bust due to the rain. Either it was raining, or the visibility was so poor you could not see. An algal bloom occurred in St. Joe Bay that closed scalloping for most of the season.

- We began a seagrass monitoring project with the University of West Florida. This was a tough year to begin due to the poor visibility, but we will continue in 2018.

- Manatee sightings were reported in Big Lagoon and Santa Rosa Sound. Again, this is not that unusual but the number of sightings, the number of manatees together, and the length of time they remained in the bay were.

- And then the mangroves – nine red mangroves were reported in Big Lagoon. Sea Grant will be working with Dauphin Island Sea Lab and resource managers from NERRS in Florida, Alabama and Mississippi to search for more mangroves in the northern Gulf in 2018.

- And the rain continued…

Rain storms are common when the Bermuda High is in the western Atlantic.

Photo: Stuart Health, NOAA

As summer moves into fall the Bermuda High typically begins to slide eastward, taking with it the “protection” from summer hurricanes – and the hurricanes came. First, it was Harvey, then Irma, then Maria, and then Nate. All had their impacts on the area.

- First were the flamingos in Pensacola, three of them, photographed in different locations around the bay – then they were gone.

- Numerous flocks of white pelicans. They typically fly through the area but there appeared to be more than we normally see and reports of them landing across the area increased.

- We received calls about “invasive” plants growing in the bayou – which turned out to be freshwater plants that had taken advantage of the freshwater conditions in our bayous from the heavy rains.

- The snake encounters did not decrease

- The mangroves continued to grow

- The manatee sightings continued into the fall

- And the rain continued

How did this season fare with local seafood (Escambia County only)?

- There was a 17% decrease in the number of species harvested – from 59 to 49

- And an 11% decrease in the price/lb. fishers received for their seafood – from $2.20/lb. to $1.95/lb.

- But there was a 33% increase in the pounds of seafood reported – from 839,673 to 1,121,225 lbs.

- A 38% increase in the number of trips reported – from 2,658 to 3,664 trips

- And a 25% increase in the estimated value of the local seafood harvest – from $1,589,518 to $1,991,286 – vermillion snapper, red snapper, and striped mullet remain our top three target species.

Manatee swimming in Big Lagoon near Pensacola.

Photo: Marsha Stanton

We are now moving into winter. The Bermuda High has moved across the Atlantic. This typically begins a dry season – and it has been dry for several weeks. It also allows cold fronts to reach the coast – and they did. On December 9, it snowed in Pensacola. Who knows what 2018 will bring but we will continue to be in the field monitoring and observing. There are opportunities for locals to volunteer for some of our monitoring projects, and there are other agencies and NGOs in the area seeking volunteers for monitoring and restoration projects. Join us if you like, and have a very happy holiday season.