by Rick O'Connor | Jan 8, 2021

It’s winter…

The sky is clear, the humidity is low, the bugs are gone, and the highs are in the 60s – most days. These are perfect days to get outside and enjoy. But the water is cold and you do not want to get wet – most days. And with COVID hanging around we do not want to go where there are crowds. Where can I go to enjoy this great weather, the outdoors, but stay safe?

As the summer heat fades, the weather is great for hiking! Photo credit: Abbie Seales

Hiking…

My wife and I have already made several hikes this winter and have enjoyed each one. Each panhandle county has several hiking trails you could visit. In our county there are city, county, state, and federal trails to choose from. The Florida Trail begins in Escambia County, at Ft. Pickens on Santa Rosa Island, and dissects each county in the panhandle on its way to the Everglades. You could find the section running through yours and hike that for a day. Community parks, our local university, state and national parks, and the water management district, all have trails.

Some are a short loops and easy. Others can be 20 plus miles, but you do not have to hike it all. Go for as long as you like and then return to the car. Some are handicapped access, some have paved sections, or boardwalks. Some go along waterways and the water is so clear in the winter that you can see to the bottom. Many meander through both open areas and areas with a closed tree canopies.

The tracks of the very common armadillo.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

The boardwalk of Deer Lake State Park off of Highway 30-A. you can see the tracks of several types of mammals who pass under at night.

Being winter, the wildlife viewing may be less. The “warm bloods” are moving – birds and mammals. Actually, the birds are everywhere, it is a great time to go birding if you like that. Mammals are still more active at dawn dusk, but their tracks are everywhere. We have seen raccoon, coyote, and deer on many of our hikes. But the insects are down as well. We have not had a yellow fly or mosquito gives us a problem yet. Some fear snakes, we actually like the see them, but we have not. Many will come out of their dens when the days warm and the sun is out to bask for a bit before retreating back into their lair. You might feel more comfortable hiking knowing the chance of an encounter one this time of year is much less.

One of the many Florida State Forest trails in South Walton.

The Florida Trail extends (in sections) over 1,300 miles from Ft. Pickens to the Florida Everglades. It begins at this point.

But the views are great and the photography excellent. Some mornings we have had fog issues, but it quickly lifts, and the bay is often slick as glass with pelicans, loons, and cormorants paddling around. These have made for some great photos.

Things to consider for your hike.

Good shoes. Many of the trails we have hiked have had wet and muddy sections.

Temperature. There can be big swings when going from open sunny areas to under the tree canopies. Wear clothes in layers and have a backpack that can hold what you want to take off. Some like to wear the fleece vests so they do not have to put on/remove as they hike.

Water. I bring at least 32 ounces. It is not hot, but water is still needed.

Snacks. Always a plus. I always miss them when I do not have them.

Camera. Again, the scenery and the birds are really good right now.

The best thing is that you are getting outside, getting exercise, and getting away from the crazy world that is going on right now. Take a “mind break” and take a hike.

Here are some hikes suggested by hiking guides.

Gulf Islands National Seashore / Ft. Pickens – Florida Trail (Ft. Pickens section) – 2 miles – Pensacola Beach

Blackwater State Forest – Jackson Red Ground Trail – 21 miles – near Munson FL

Falling Waters State Park – Falls, Sinkhole, and Wiregrass Trail – ~ 1 mile – near Chipley on I-10

Grayton Beach State Park – Dune Forest Trail – < 1 mile – 30-A in Walton County

T.H. Stone Memorial St. Joseph Peninsula State Park – Beach Walk and Wilderness Preserve Trail – ~ 9 miles – near Port St. Joe FL

Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravine Preserve – Garden of Eden Trail – 4 mile loop – Hwy 12 near Bristol FL

Torreya State Park – Torreya River Bluff Loop Trail – 7 mile loop – Hwy 271 near Bristol

Leon Sinks Geological Area – Sinkhole and Gumswamp Trail – 3 mile loop – US 319 near Tallahassee

Edward Ball Wakulla Springs State Park – Sally Ward Springs and Hammock Trails – 2.5 miles out and back – Hwy 20 near Wakulla FL

St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge – Stoney Bayou Trail – ~ 6 miles – CR 59 near Gulf of Mexico

by Laura Tiu | Dec 3, 2020

Fall is such a spectacular time in the Florida Panhandle. The crowds are gone and the thermometer rests at a pleasant 50-70-something degrees. It is the perfect time of year to enjoy our amazing environment. Nature has a magical way of boosting our energy levels and immune systems and improving mood and focus. We can all use a heaping helping of that right now.

So where do you start? Here are some ideas.

Take in a sunrise or sunset. The beach is often one of the best places to do this, but anywhere will do. Last weekend, I was at the Okaloosa Island Boardwalk and Pier and the sunset was magnificent. While there, take a walk along the beach, let the cool sand squish between your toes and discover what might be hiding in the wrack. The wrack is that line of seaweed deposited after high tide. Upon close inspection, it contains many treasures including seagrasses, sponges, shells, worm tubes, small crabs and other oddities.

Take in a sunrise or sunset. The beach is often one of the best places to do this, but anywhere will do. Last weekend, I was at the Okaloosa Island Boardwalk and Pier and the sunset was magnificent. While there, take a walk along the beach, let the cool sand squish between your toes and discover what might be hiding in the wrack. The wrack is that line of seaweed deposited after high tide. Upon close inspection, it contains many treasures including seagrasses, sponges, shells, worm tubes, small crabs and other oddities.

Take a nature hike. I love the nature trails at our local state and national parks, Henderson Beach, Topsail, Blackwater and Grayton Beach State Parks all have great trails. You may see some wildflowers this time of year. Look for animal tracks and resident birds. You may also see some monarch butterflies on the saltbush, resting as they continue their migration to Mexico.

Check out the springs. Morrison Springs and Ponce de Leon Springs in the state park in Walton County are an easy drive. Sit and enjoy the beauty and peaceful nature that surrounds the springs. Dip your toes in the cool water for a refreshing tingle or jump right in if you dare.

If you have a kayak, canoe or paddle board, it’s a great time to be on the water. Look for migrating shorebirds, schools of fish or pods of dolphins. Did you know we have over 60 dolphins that call the Destin area home year-round? You can often find them cruising in the Choctawhatchee Bay, or hop aboard one of our local dolphin cruises to catch a better glimpse.

Finally, our local fresh seafood is available year-round. Plan a picnic with some fresh shrimp or smoked mullet dip. Seafood offers many of the same benefits as time in nature, so double up on all the goodness that fall has to offer. Get outside and get happy!

by Daniel J. Leonard | Nov 18, 2020

The native Florida landscape definitely isn’t known for its fall foliage. But as you might have noticed, there is one species that reliably turns shades of red, orange, yellow and sometimes purple, it also unfortunately happens to be one of the most significant pest plant species in North America, the highly invasive Chinese Tallow or Popcorn Tree (Triadica sebifera).

Chinese Tallow fall foliage. Photo courtesy of Daniel Leonard.

Native to temperate areas of China and introduced into the United States by Benjamin Franklin (yes, the Founding Father!) in 1776 for its seed oil potential and outstanding ornamental attributes, Chinese Tallow is indeed a pretty tree, possessing a tame smallish stature, attractive bark, excellent fall color and interesting white “popcorn” seeds. In addition, Chinese Tallow’s climate preferences make it right at home in the Panhandle and throughout the Southeast. It requires no fertilizer, is both drought and inundation tolerant, is both sun and shade tolerant, has no serious pests, produce seed preferred by wildlife (birds mostly) and is easy to propagate from seed (a mature

Chinese Tallow tree can produce up to 100,000 seeds annually!). While these characteristics indeed make it an awesome landscape plant and explain it being passed around by early American colonists, they are also the very reasons that make the species is one of the most dangerous invasives – it can take over any site, anywhere.

While Chinese Tallow can become established almost anywhere, it prefers wet, swampy areas and waste sites. In both settings, the species’ special adaptations allow it a competitive advantage over native species and enable it to eventually choke the native species out altogether.

In low-lying wetlands, Chinese Tallow’s ability to thrive in both extreme wet and droughty conditions enable it to grow more quickly than the native species that tend to flourish in either one period or the other. In river swamps, cypress domes and other hardwood dominated areas, Chinese Tallow’s unique ability to easily grow in the densely shaded understory allows it to reach into the canopy and establish a foothold where other native hardwoods cannot. It is not uncommon anymore to venture into mature swamps and cypress domes and see hundreds or thousands of Chinese Tallow seedlings taking over the forest understory and encroaching on larger native tree species. Finally, in waste areas, i.e. areas that have been recently harvested of trees, where a building used to be, or even an abandoned field, Chinese Tallow, with its quick germinating, precocious nature, rapidly takes over and then spreads into adjacent woodlots and natural areas.

Chinese tallow seedlings colonizing a “waste” area. Photo courtesy of Daniel Leonard.

Hopefully, we’ve established that Chinese Tallow is a species that you don’t want on your property and has no place in either landscapes or natural areas. The question now is, how does one control Chinese Tallow?

- Prevention is obviously the first option. NEVER purposely plant Chinese Tallow and do not distribute the seed, even as decorations, as they are sometimes used.

- The second method is physical removal. Many folks don’t have a Chinese Tallow in their yard, but either their neighbors do, or the natural area next door does. In this situation, about the best one can do is continually pull up the seedlings once they sprout. If a larger specimen in present, cut it down as close to the ground as possible. This will make herbicide application and/or mowing easier.

- The best option in many cases is use of chemical herbicides. Both foliar (spraying green foliage on smaller saplings) and basal bark applications (applying a herbicide/oil mixture all the way around the bottom 15” of the trunk. Useful on larger trees or saplings in areas where it isn’t feasible to spray leaves) are effective. I’ve had good experiences with both methods. For small trees, foliar applications are highly effective and easy. But, if the tree is taller than an average person, use the basal bark method. It is also very effective and much less likely to have negative consequences like off-target herbicide drift and applicator exposure. Finally, when browsing the herbicide aisle garden centers and farm stores, look for products containing the active ingredient Triclopyr, the main chemical in brands like Garlon, Brushtox, and other “brush/tree & stump killers”. Mix at label rates for control.

Despite its attractiveness, Chinese Tallow is an insidious invader that has no place in either landscapes or natural areas. But with a little persistence and a quality control plan, you can rid your property of Chinese Tallow! For more information about invasive plant management and other agricultural topics, please contact your local UF/IFAS Extension office!

References:

Langeland, K.A, and S. F. Enloe. 2018. Natural Area Weeds: Chinese Tallow (Sapium sebiferum L.). Publication #SS-AGR-45. Printer friendly PDF version: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/AG/AG14800.pdf

by Mark Mauldin | Oct 23, 2020

Archery season for white tailed deer opens this Saturday (10/24/20) in FWC Hunting Zone D (basically the Panhandle west of Tallahassee, see figure 1). Before you go hunting be sure that you have a plan in place for logging and reporting your harvest. Last year FWC implemented a mandatory harvest reporting system. That system is still in effect this year but with some modifications.

Figure 1. FWC Hunting Zone D

myfwc.com

The most notable change to the harvest reporting system this year is with the associated smart phone app. There is a new app this year – Fish|Hunt Florida. This new app will replace the Survey123 for ArcGIS app that was used last year.

In my opinion, the logging and reporting function on the Fish|Hunt Florida app is simpler to use than the previous app. Additionally the Fish|Hunt Florida app has many other useful features. A few highlights include; the ability to view and purchase hunting and fishing licenses/permits through the app, interactive versions of hunting and fishing regulations, and several other handy resources for sportsmen including, marine forecasts, tides, wildlife feeding times, sunrise & sunset times, boat ramp locator and a current location feature. Screenshots from the app are included below. The Fish|Hunt Florida app is available for free through the Apple App Store and the Google Play Store.

Remember, the current regulations state that your deer harvest must be logged before the animal is moved. Take a minute or two to install the app on your phone before you go hunting. Using the app allows logging and reporting to happen simultaneously. The app can be used for logging and reporting a harvest even in areas where cell service is poor. Harvest information will can be saved and the app will automatically complete the process as soon as adequate cell service is available. The alternative to using the app is a two-step process, the harvest can be logged (prior to being moved) on a paper form and then reported by calling 888-HUNT-FLORIDA (888-486-8356) or going to GoOutdoorsFlorida.com within 24 hours.

Follow the link for specific instructions for logging and reporting a harvested deer using the Fish|Hunt Florida app; don’t worry, it’s easy. Fish|Hunt Florida app instructions

For more information on the Fish|Hunt Florida app and the FWC Deer Harvest Reporting System visit myfwc.com.

Screenshot of the Boat Info tab from the Hunt|Fish Florida App. Click on the image to make it larger.

Screenshot of the Fishing Tab from the Hunt|Fish Florida App. Click on the image to make it larger.

Screenshot of the Home screen from the Hunt|Fish Florida App. Click on the image to make it larger.

Screenshot of the Hunting tab from the Hunt|Fish Florida App. Click on the image to make it larger.

by Daniel J. Leonard | Sep 3, 2020

Overcup on the edge of a wet weather pond in Calhoun County. Photo courtesy of Daniel Leonard.

Haunting alluvial river bottoms and creek beds across the Deep South, is a highly unusual oak species, Overcup Oak (Quercus lyrata). Unlike nearly any other oak, and most sane people, Overcups occur deep in alluvial swamps and spend most of their lives with their feet wet. Though the species hides out along water’s edge in secluded swamps, it has nevertheless been discovered by the horticultural industry and is becoming one of the favorite species of landscape designers and nurserymen around the South. The reasons for Overcup’s rise are numerous, let’s dive into them.

The same Overcup Oak thriving under inundation conditions 2 weeks after a heavy rain. Photo courtesy Daniel Leonard.

First, much of the deep South, especially in the Coastal Plain, is dominated by poorly drained flatwoods soils cut through by river systems and dotted with cypress and blackgum ponds. These conditions call for landscape plants that can handle hot, humid air, excess rainfall, and even periodic inundation (standing water). It stands to reason our best tree options for these areas, Sycamore, Bald Cypress, Red Maple, and others, occur naturally in swamps that mimic these conditions. Overcup Oak is one of these hardy species. It goes above and beyond being able to handle a squishy lawn, and is often found inundated for weeks at a time by more than 20’ of water during the spring floods our river systems experience. The species has even developed an interested adaptation to allow populations to thrive in flooded seasons. Their acorns, preferred food of many waterfowl, are almost totally covered by a buoyant acorn cap, allowing seeds to float downstream until they hit dry land, thus ensuring the species survives and spreads. While it will not survive perpetual inundation like Cypress and Blackgum, if you have a periodically damp area in your lawn where other species struggle, Overcup will shine.

Overcup Oak leaves in August. Note the characteristic “lyre” shape. Photo courtesy Daniel Leonard.

Overcup Oak is also an exceedingly attractive tree. In youth, the species is extremely uniform, with a straight, stout trunk and rounded “lollipop” canopy. This regular habit is maintained into adulthood, where it becomes a stately tree with a distinctly upturned branching habit, lending itself well to mowers and other traffic underneath without having to worry about hitting low-hanging branches. The large, lustrous green leaves are lyre-shaped if you use your imagination (hence the name, Quercus lyrata) and turn a not-unattractive yellowish brown in fall. Overcups especially shine in the winter when the whitish gray shaggy bark takes center stage. The bark is very reminiscent of White Oak or Shagbark Hickory and is exceedingly pretty relative to other landscape trees that can be successfully grown here.

Finally, Overcup Oak is among the easiest to grow landscape trees. We have already discussed its ability to tolerate wet soils and our blazing heat and humidity, but Overcups can also tolerate periodic drought, partial shade, and nearly any soil pH. They are long-lived trees and have no known serious pest or disease problems. They transplant easily from standard nursery containers or dug from a field (if it’s a larger specimen), making establishment in the landscape an easy task. In the establishment phase, defined as the first year or two after transplanting, young transplanted Overcups require only a weekly rain or irrigation event of around 1” (wetter areas may not require any supplemental irrigation) and bi-annual applications of a general purpose fertilizer, 10-10-10 or similar. After that, they are generally on their own without any help!

Typical shaggy bark on 7 year old Overcup Oak. Photo courtesy Daniel Leonard.

If you’ve been looking for an attractive, low-maintenance tree for a pond bank or just generally wet area in your lawn or property, Overcup Oak might be your answer. For more information on Overcup Oak, other landscape trees and native plants, give your local UF/IFAS County Extension office a call!

by Rick O'Connor | Jun 26, 2020

This is a good name for this group. They are mollusk that have two shells. They tried “univalve” with the snails and slugs, but that never caught on – gastropods it is for them. The bivalves are an interesting, and successful, group. They have taken the shell for protection idea to the limit – they are COMPLETELY covered with shell. No predators… no way. But they do have predators – we will talk more on that.

An assortment of bivalves, mostly bay scallop.

Photo: Florida Department of Environmental Protection.

As you might expect, with the increase in shell there is a decrease in locomotion – as a matter of fact, many species do not move at all (they are sessile). But in a sense, they do not care. They are completely covered and protected. Again, we will talk more about how well that works.

The two shells (valves) are connected on the dorsal side of the animal and hinged together by a ligament. Their bodies are laterally compressed to fit into a shell that is aerodynamic for burrowing through soft muds and sands. Their “heads” are greatly reduced (even missing in some) but they do have a sensory system. Along the edge of the mantle chemoreceptive cells (smell and taste) can be found and many have small ocelli, which can detect light. The scallops take it a step further by having actually eyes – but they do live on the surface and they do move around – so they are needed.

The shells are hinged together at the umbo with “teeth like structures and the shells open and close using a pair of adductor muscles. Many shells found on the beach will have “scars” which are the point of contact for these muscles. They range is size from the small seed clams (2mm – 0.08”) to the giant clam of the Indo-Pacific (1m – 3.4 ft) and 2500 lbs.! Most Gulf bivalves are more modest in size.

Being slow burrowing benthic animals, sand and mud can become a problem when feeding and breathing. In response, many bivalves have developed modified gills to help remove this debris, and many actually remove organic particles using it as a source of food. Many others will fuse their mantle to the shell not allowing sediment to enter. But some still does and, if not removed, will be covered by a layer of nacreous material forming pearls. All bivalves can produce pearls. Only those with large amounts of nacreous material produce commercially valuable ones.

Coquina are a common burrowing clam found along our beaches.

Photo: Flickr

Another feature is the large foot, used for digging a burrowing in the more primitive forms. It is the foot we eat when we eat clams. They can turn their bodies towards the substrate, begin digging with their foot but also using their excurrent from breathing to form a sort of jet to help move and loosen the sand as they go – very similar to the way we set pilings for piers and bridges today.

These are the earliest forms of bivalves – the burrowers. Most are known as clams and most live where the sediment is soft. Located near their foot is a sense organ called a statocyst that lets them know their orientation in the environment. Most have their mantles fused to their shells so sand cannot enter the empty spaces in the body. To channel water to the gills, they have developed tubes called siphons which act as snorkels. Most burrow only a few inches, some burrow very deep and they are even more streamlined and elongated.

Some have evolved to burrow into harder material such as coral or wood. One of the more common ones is an animal called a shipworm. Called this by mariners because of the tunnels they dig throughout the hulls of wooden ships, they are not worms but a type of clam that have learned to burrow through the wood consuming the sawdust of their actions. They have very reduced shells and a very long foot.

This cluster of green mussels occupies space that could be occupied by bivavles like osyters.

Other bivalves secrete a fibrous thread from their foot that is used to grab, hold, and sometimes pull the animal along. These are called byssal threads. Many will secrete hundreds of these, allow them to “tan” or dry, reduce their foot, and now are attached by these threads. The most famous of this group are the mussels. Mussels are a popular seafood product and are grown commercial having them attach to ropes hanging in the water.

Another method of attachment is to literally cement your self to the bottom. Those bivalves who do this will usually lay on their side when they first settle out from their larval stage and attach using a fluid produced by the animal. This fluid eventually cements them to the bottom and the shell attached is usually longer than the other side, which is facing the environment. The most famous of these are the oysters. Oysters basically have lost both their “head” and the foot found in other bivalves. These sessile bivalves are very dependent on tides and currents to help clear waste and mud from their bodies.

Oysters are a VERY popular seafood product along the Gulf coast.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Then there are the bivalves who actually live on the bottom – not attached – and are able to move, or even swim. Most of these have well developed tentacles and ocelli to detect danger in the environment and some, like the scallops, can actually “clap their shells together” to create a jet current and swim. This is usually done when they detect danger, such as a starfish, and they have been known to swim up to three feet. Some will use this jet as a means of digging a depression in the sand they can settle in. In this group, the adductor has been reduced from two (the number usually found in bivalves) to one, and the foot is completely gone.

As you might guess, reproduction is external in this group. Most have male and female members but some species (such as scallops and shipworms) are hermaphroditic. The gametes are released externally at the same time in an event called a mass spawning. To trigger when this should happen, the bivalves pay attention to water temperature, tides, and pheromones released by the opposite sex or by the release of the gametes themselves.

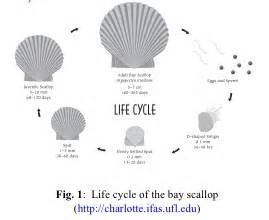

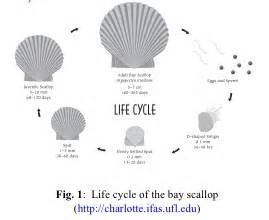

Scallop life cycle.

Image: University of Florida IFAS

The fertilized eggs quickly develop into a planktonic larva known as a veliger. This veliger is ciliated and can swim with the current to find a suitable settling spot. Some species have long lived veliger stages. Oysters are such and the dispersal of their veliger can travel as far as 800 miles! Once the larval stage ends, they settle as “spat” (baby shelled bivalves) on the substrate and begin their lives. Some species (such as scallop) only live for a year or two. Others can live up to 10 years.

As a group, bivalves are filter feeders, filtering organic particles and phytoplankton as small as 1 micron (1/1,000,000-m… VERY small). In doing this they do an excellent job of increasing water clarity which benefits many other creatures in the community. As a matter of fact, many could not survive without this “eco-service” and the loss of bivalves has triggered the loss of both habitat and species in the Gulf region. Restoration efforts (particularly with oysters) is as much for the enhancement of the environment and diversity as it is for the commercial value of the oyster.

Now… predators… yes, they have many. Though they have completely covered their bodies with shell, there are many animals that have learned to “get in there”. Starfish and octopus are famous for their abilities to open tightly closed shells. Rays, some fish, and some turtles and birds have modified teeth (or bills) to crush the shell or cut the adductor muscle. Sea otters have learned the trick to crush them with rocks and some local shorebirds will drop them on roads and cars trying to access them. And then there are humans. We steam them to open the shell and cut their adductor muscle to reach the sweet meat inside.

It is a fascinating group – and a commercial valuable one as well. Lots of bivalves are consumed in some form or fashion worldwide. Take some time at the beach to collect their shells as enjoy the great diversity and design within this group. EMBRACE THE GULF!

Take in a sunrise or sunset. The beach is often one of the best places to do this, but anywhere will do. Last weekend, I was at the Okaloosa Island Boardwalk and Pier and the sunset was magnificent. While there, take a walk along the beach, let the cool sand squish between your toes and discover what might be hiding in the wrack. The wrack is that line of seaweed deposited after high tide. Upon close inspection, it contains many treasures including seagrasses, sponges, shells, worm tubes, small crabs and other oddities.

Take in a sunrise or sunset. The beach is often one of the best places to do this, but anywhere will do. Last weekend, I was at the Okaloosa Island Boardwalk and Pier and the sunset was magnificent. While there, take a walk along the beach, let the cool sand squish between your toes and discover what might be hiding in the wrack. The wrack is that line of seaweed deposited after high tide. Upon close inspection, it contains many treasures including seagrasses, sponges, shells, worm tubes, small crabs and other oddities.