by Sheila Dunning | Jan 28, 2021

Groundhog

Groundhog Day is celebrated every year on February 2, and in 2021, it falls on Tuesday. It’s a day when townsfolk in Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania, gather in Gobbler’s Knob to watch as an unsuspecting furry marmot is plucked from his burrow to predict the weather for the rest of the winter. If Phil does see his shadow (meaning the Sun is shining), winter will not end early, and we’ll have another 6 weeks left of it. If Phil doesn’t see his shadow (cloudy) we’ll have an early spring. Since Punxsutawney Phil first began prognosticating the weather back in 1887, he has predicted an early end to winter

only 18 times. However, his accuracy rate is only 39%. In the south, we call also defer to General Beauregard Lee in Atlanta, Georgia or Pardon Me Pete in Tampa, Florida.

But, what is a groundhog? Are gophers and groundhogs the same animal? Despite their similar appearances and burrowing habits, groundhogs and gophers don’t have a whole lot in common—they don’t even belong to the same family. For example, gophers belong to the family Geomyidae, a group that includes pocket gophers, kangaroo rats, and pocket mice. Groundhogs, meanwhile, are members of the Sciuridae (meaning shadow-tail) family and belong to the genus Marmota. Marmots are diurnal ground squirrels. There are 15 species of marmot, and groundhogs are one of them.

Science aside, there are plenty of other visible differences between the two animals. Gophers, for example, have hairless tails, protruding yellow or brownish teeth, and fur-lined cheek pockets for storing food—all traits that make them different from groundhogs. The feet of gophers are often pink, while groundhogs have brown or black feet. And while the tiny gopher tends to weigh around two or so pounds, groundhogs can grow to around 13 pounds.

While both types of rodent eat mostly vegetation, gophers prefer roots and tubers while groundhogs like vegetation and fruits. This means that the former animals rarely emerge from their burrows, while the latter are more commonly seen out and about. In the spring, gophers make what is called eskers, or winding mounds of soil. The southeastern pocket gopher, Geomys pinetis, is also known as the sandy-mounder in Florida.

Southeastern Pocket Gopher

The southeastern pocket gopher is tan to gray-brown in color. The feet and naked tail are light colored. The southeastern pocket gopher requires deep, well-drained sandy soils. It is most abundant in longleaf pine/turkey oak sandhill habitats, but it is also found in coastal strand, sand pine scrub, and upland hammock habitats.

Gophers dig extensive tunnel systems and are rarely seen on the surface. The average tunnel length is 145 feet (44 m) and at least one tunnel was followed for 525 feet (159 m). The soil gophers remove while digging their tunnels is pushed to the surface to form the characteristic rows of sand mounds. Mound building seems to be more intense during the cooler months, especially spring and fall, and slower in the summer. In the spring, pocket gophers push up 1-3 mounds per day. Based on mound construction, gophers seem to be more active at night and around dusk and dawn, but they may be active at any time of day.

Pocket Gopher Mounds

Many amphibians and reptiles use pocket gopher mounds as homes, including Florida’s unique mole skinks. The pocket gopher tunnels themselves serve as habitat for many unique invertebrates found nowhere else.

So, groundhogs for guesses on the arrival of spring. But, when the pocket gophers are making lots of mounds, spring is truly here. Happy Groundhog’s Day.

by Andrea Albertin | Jan 28, 2021

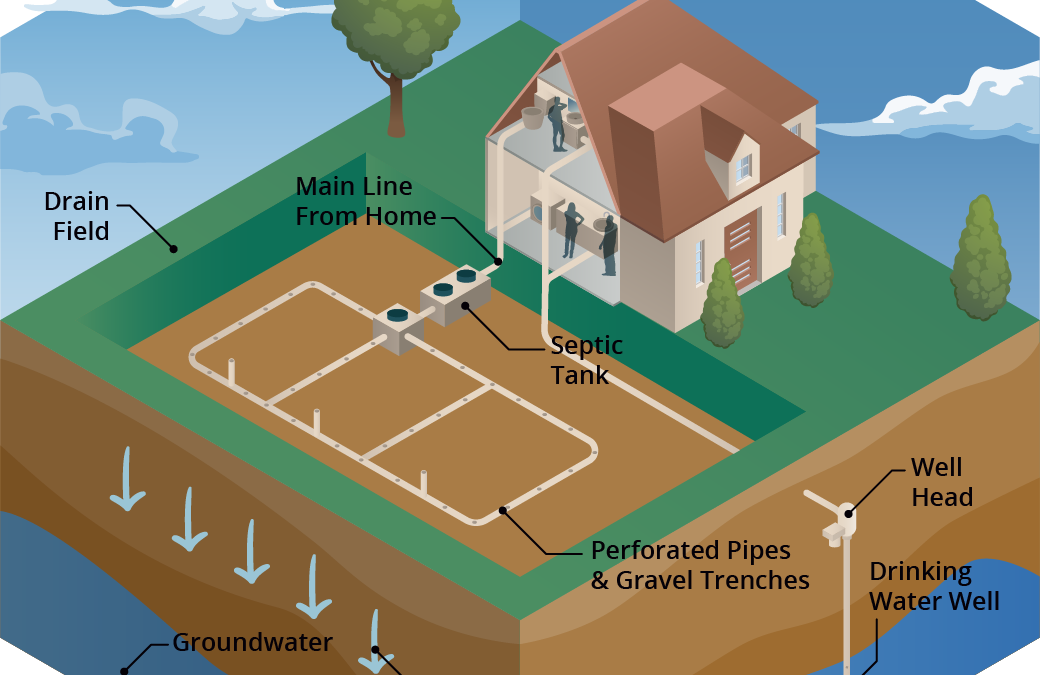

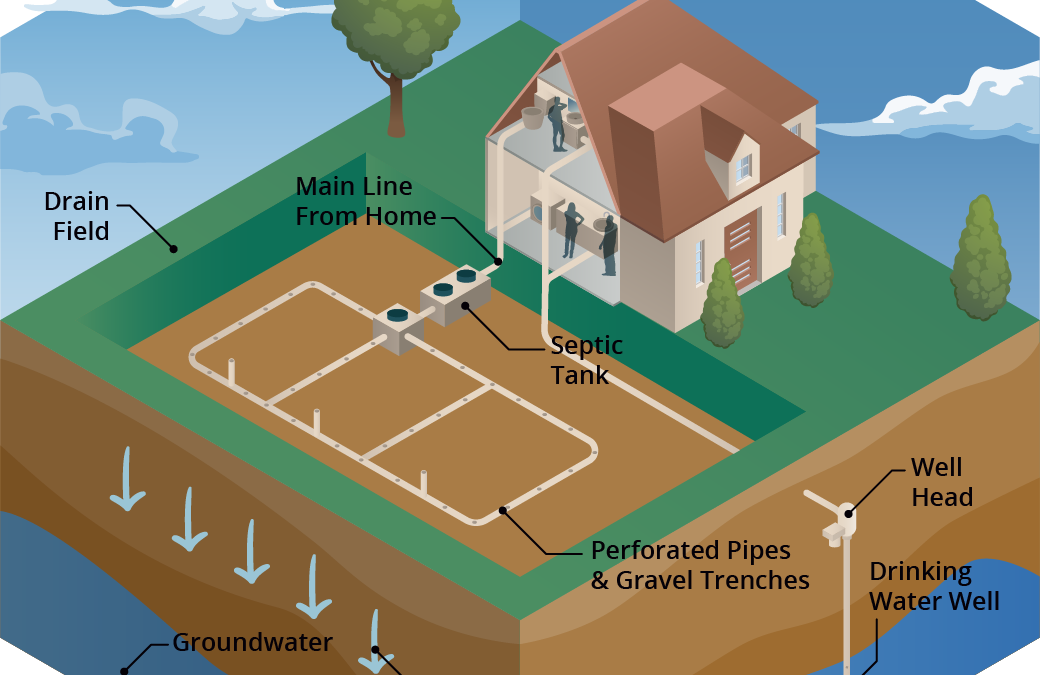

Senate Bill 712 ‘The Clean Waterways Act’ was signed into Florida law on June 30, 2020. The purpose of the bill is to better protect Florida’s water resources and focuses on minimizing the impact of known sources of nutrient pollution. These sources include septic systems, wastewater treatment plants, stormwater runoff as well as fertilizer used in agricultural production.

Senate Bill 712 focuses on protecting Florida’s water resources such as Jackson Blue Springs/Merritt’s Mill Pond, pictured here. Credit: Doug Mayo, UF/IFAS.

What major provisions are included in SB 712?

Primary actions required by SB712 were listed in a news release by Governor Desantis’ staff in June 2020 as:

- Regulation of septic systems as a source of nutrients and transfer of oversight from the Florida Department of Health (DOH) to the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (DEP).

- Contingency plans for power outages to minimize discharges of untreated wastewater for all sewage disposal facilities.

- Provision of financial records from all sanitary sewage disposal facilities so that DEP can ensure funds are being allocated to infrastructure upgrades, repairs, and maintenance that prevent systems from falling into states of disrepair.

- Detailed documentation of fertilizer use by agricultural operations to ensure compliance with Best Management Practices (BMPs) and aid in evaluation of their effectiveness.

- Updated stormwater rules and design criteria to improve the performance of stormwater systems statewide to specifically address nutrients.

How does the bill impact septic system regulation?

The transfer of the Onsite Sewage Program (OSP) (commonly known as the septic system program) from DOH to DEP becomes effective on July 1, 2021. So far, DOH and DEP submitted a report to the Governor and Legislature at the end of 2020 with recommendations on how this transfer should take place. They recommend that county DOH employees working in the OSP continue implementing the program as DOH-employees, but that the onsite sewage program office in the State Health Office transfer to DEP and continue working from there. DOH created an OSP Transfer web page where updates and documents related to the transfer are posted.

How does the bill impact agricultural operations?

SB 712 affects all landowners and producers enrolled in the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (FDACS) BMP Program. Under this bill:

- Every two years FDACS will make an onsite implementation verification (IV) visit to land enrolled in the BMP program to ensure that BMPs are properly implemented. These visits will be coordinated between the producer and field staff from FDACS Office of Agriculture and Water Policy (OAWP).

- During these visits (and as they have done in the past), field staff will review records that producers are required to keep under the BMP program.

- Field staff will also collect information on nitrogen and phosphorus application. FDACS has created a specific form, the Nutrient Application Record Keeping Form or NARF where producers will record quantities of N and P applied. FDACS field staff will retain a copy of the NARF during the IV visit.

FDACS-OAWP prepared a thorough document with responses to SB 712 Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ’s). It includes responses to questions about site visits, the NARF and record keeping, why FDACS is collecting nutrient records and what will be done with this information. The fertilizer records collected are not public information, and are protected under the public records exemption (Section 403.067 Florida Statutes). For areas that fall under a Basin Management Action Plan (like the Jackson Blue and Wakulla Springs Basins in the Florida Panhandle), FDACS will combine the nitrogen and phosphorus application data from all enrolled properties (total pounds of N and P applied within the BMAP). It will then send the aggregated nutrient application information to FDEP.

Details of how all aspects of SB 712 will be implemented are still being worked out and we should continue to hear more in the coming months.

by Rick O'Connor | Jan 8, 2021

It’s winter…

The sky is clear, the humidity is low, the bugs are gone, and the highs are in the 60s – most days. These are perfect days to get outside and enjoy. But the water is cold and you do not want to get wet – most days. And with COVID hanging around we do not want to go where there are crowds. Where can I go to enjoy this great weather, the outdoors, but stay safe?

As the summer heat fades, the weather is great for hiking! Photo credit: Abbie Seales

Hiking…

My wife and I have already made several hikes this winter and have enjoyed each one. Each panhandle county has several hiking trails you could visit. In our county there are city, county, state, and federal trails to choose from. The Florida Trail begins in Escambia County, at Ft. Pickens on Santa Rosa Island, and dissects each county in the panhandle on its way to the Everglades. You could find the section running through yours and hike that for a day. Community parks, our local university, state and national parks, and the water management district, all have trails.

Some are a short loops and easy. Others can be 20 plus miles, but you do not have to hike it all. Go for as long as you like and then return to the car. Some are handicapped access, some have paved sections, or boardwalks. Some go along waterways and the water is so clear in the winter that you can see to the bottom. Many meander through both open areas and areas with a closed tree canopies.

The tracks of the very common armadillo.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

The boardwalk of Deer Lake State Park off of Highway 30-A. you can see the tracks of several types of mammals who pass under at night.

Being winter, the wildlife viewing may be less. The “warm bloods” are moving – birds and mammals. Actually, the birds are everywhere, it is a great time to go birding if you like that. Mammals are still more active at dawn dusk, but their tracks are everywhere. We have seen raccoon, coyote, and deer on many of our hikes. But the insects are down as well. We have not had a yellow fly or mosquito gives us a problem yet. Some fear snakes, we actually like the see them, but we have not. Many will come out of their dens when the days warm and the sun is out to bask for a bit before retreating back into their lair. You might feel more comfortable hiking knowing the chance of an encounter one this time of year is much less.

One of the many Florida State Forest trails in South Walton.

The Florida Trail extends (in sections) over 1,300 miles from Ft. Pickens to the Florida Everglades. It begins at this point.

But the views are great and the photography excellent. Some mornings we have had fog issues, but it quickly lifts, and the bay is often slick as glass with pelicans, loons, and cormorants paddling around. These have made for some great photos.

Things to consider for your hike.

Good shoes. Many of the trails we have hiked have had wet and muddy sections.

Temperature. There can be big swings when going from open sunny areas to under the tree canopies. Wear clothes in layers and have a backpack that can hold what you want to take off. Some like to wear the fleece vests so they do not have to put on/remove as they hike.

Water. I bring at least 32 ounces. It is not hot, but water is still needed.

Snacks. Always a plus. I always miss them when I do not have them.

Camera. Again, the scenery and the birds are really good right now.

The best thing is that you are getting outside, getting exercise, and getting away from the crazy world that is going on right now. Take a “mind break” and take a hike.

Here are some hikes suggested by hiking guides.

Gulf Islands National Seashore / Ft. Pickens – Florida Trail (Ft. Pickens section) – 2 miles – Pensacola Beach

Blackwater State Forest – Jackson Red Ground Trail – 21 miles – near Munson FL

Falling Waters State Park – Falls, Sinkhole, and Wiregrass Trail – ~ 1 mile – near Chipley on I-10

Grayton Beach State Park – Dune Forest Trail – < 1 mile – 30-A in Walton County

T.H. Stone Memorial St. Joseph Peninsula State Park – Beach Walk and Wilderness Preserve Trail – ~ 9 miles – near Port St. Joe FL

Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravine Preserve – Garden of Eden Trail – 4 mile loop – Hwy 12 near Bristol FL

Torreya State Park – Torreya River Bluff Loop Trail – 7 mile loop – Hwy 271 near Bristol

Leon Sinks Geological Area – Sinkhole and Gumswamp Trail – 3 mile loop – US 319 near Tallahassee

Edward Ball Wakulla Springs State Park – Sally Ward Springs and Hammock Trails – 2.5 miles out and back – Hwy 20 near Wakulla FL

St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge – Stoney Bayou Trail – ~ 6 miles – CR 59 near Gulf of Mexico

by Laura Tiu | Dec 3, 2020

Fall is such a spectacular time in the Florida Panhandle. The crowds are gone and the thermometer rests at a pleasant 50-70-something degrees. It is the perfect time of year to enjoy our amazing environment. Nature has a magical way of boosting our energy levels and immune systems and improving mood and focus. We can all use a heaping helping of that right now.

So where do you start? Here are some ideas.

Take in a sunrise or sunset. The beach is often one of the best places to do this, but anywhere will do. Last weekend, I was at the Okaloosa Island Boardwalk and Pier and the sunset was magnificent. While there, take a walk along the beach, let the cool sand squish between your toes and discover what might be hiding in the wrack. The wrack is that line of seaweed deposited after high tide. Upon close inspection, it contains many treasures including seagrasses, sponges, shells, worm tubes, small crabs and other oddities.

Take in a sunrise or sunset. The beach is often one of the best places to do this, but anywhere will do. Last weekend, I was at the Okaloosa Island Boardwalk and Pier and the sunset was magnificent. While there, take a walk along the beach, let the cool sand squish between your toes and discover what might be hiding in the wrack. The wrack is that line of seaweed deposited after high tide. Upon close inspection, it contains many treasures including seagrasses, sponges, shells, worm tubes, small crabs and other oddities.

Take a nature hike. I love the nature trails at our local state and national parks, Henderson Beach, Topsail, Blackwater and Grayton Beach State Parks all have great trails. You may see some wildflowers this time of year. Look for animal tracks and resident birds. You may also see some monarch butterflies on the saltbush, resting as they continue their migration to Mexico.

Check out the springs. Morrison Springs and Ponce de Leon Springs in the state park in Walton County are an easy drive. Sit and enjoy the beauty and peaceful nature that surrounds the springs. Dip your toes in the cool water for a refreshing tingle or jump right in if you dare.

If you have a kayak, canoe or paddle board, it’s a great time to be on the water. Look for migrating shorebirds, schools of fish or pods of dolphins. Did you know we have over 60 dolphins that call the Destin area home year-round? You can often find them cruising in the Choctawhatchee Bay, or hop aboard one of our local dolphin cruises to catch a better glimpse.

Finally, our local fresh seafood is available year-round. Plan a picnic with some fresh shrimp or smoked mullet dip. Seafood offers many of the same benefits as time in nature, so double up on all the goodness that fall has to offer. Get outside and get happy!

by Daniel J. Leonard | Nov 18, 2020

The native Florida landscape definitely isn’t known for its fall foliage. But as you might have noticed, there is one species that reliably turns shades of red, orange, yellow and sometimes purple, it also unfortunately happens to be one of the most significant pest plant species in North America, the highly invasive Chinese Tallow or Popcorn Tree (Triadica sebifera).

Chinese Tallow fall foliage. Photo courtesy of Daniel Leonard.

Native to temperate areas of China and introduced into the United States by Benjamin Franklin (yes, the Founding Father!) in 1776 for its seed oil potential and outstanding ornamental attributes, Chinese Tallow is indeed a pretty tree, possessing a tame smallish stature, attractive bark, excellent fall color and interesting white “popcorn” seeds. In addition, Chinese Tallow’s climate preferences make it right at home in the Panhandle and throughout the Southeast. It requires no fertilizer, is both drought and inundation tolerant, is both sun and shade tolerant, has no serious pests, produce seed preferred by wildlife (birds mostly) and is easy to propagate from seed (a mature

Chinese Tallow tree can produce up to 100,000 seeds annually!). While these characteristics indeed make it an awesome landscape plant and explain it being passed around by early American colonists, they are also the very reasons that make the species is one of the most dangerous invasives – it can take over any site, anywhere.

While Chinese Tallow can become established almost anywhere, it prefers wet, swampy areas and waste sites. In both settings, the species’ special adaptations allow it a competitive advantage over native species and enable it to eventually choke the native species out altogether.

In low-lying wetlands, Chinese Tallow’s ability to thrive in both extreme wet and droughty conditions enable it to grow more quickly than the native species that tend to flourish in either one period or the other. In river swamps, cypress domes and other hardwood dominated areas, Chinese Tallow’s unique ability to easily grow in the densely shaded understory allows it to reach into the canopy and establish a foothold where other native hardwoods cannot. It is not uncommon anymore to venture into mature swamps and cypress domes and see hundreds or thousands of Chinese Tallow seedlings taking over the forest understory and encroaching on larger native tree species. Finally, in waste areas, i.e. areas that have been recently harvested of trees, where a building used to be, or even an abandoned field, Chinese Tallow, with its quick germinating, precocious nature, rapidly takes over and then spreads into adjacent woodlots and natural areas.

Chinese tallow seedlings colonizing a “waste” area. Photo courtesy of Daniel Leonard.

Hopefully, we’ve established that Chinese Tallow is a species that you don’t want on your property and has no place in either landscapes or natural areas. The question now is, how does one control Chinese Tallow?

- Prevention is obviously the first option. NEVER purposely plant Chinese Tallow and do not distribute the seed, even as decorations, as they are sometimes used.

- The second method is physical removal. Many folks don’t have a Chinese Tallow in their yard, but either their neighbors do, or the natural area next door does. In this situation, about the best one can do is continually pull up the seedlings once they sprout. If a larger specimen in present, cut it down as close to the ground as possible. This will make herbicide application and/or mowing easier.

- The best option in many cases is use of chemical herbicides. Both foliar (spraying green foliage on smaller saplings) and basal bark applications (applying a herbicide/oil mixture all the way around the bottom 15” of the trunk. Useful on larger trees or saplings in areas where it isn’t feasible to spray leaves) are effective. I’ve had good experiences with both methods. For small trees, foliar applications are highly effective and easy. But, if the tree is taller than an average person, use the basal bark method. It is also very effective and much less likely to have negative consequences like off-target herbicide drift and applicator exposure. Finally, when browsing the herbicide aisle garden centers and farm stores, look for products containing the active ingredient Triclopyr, the main chemical in brands like Garlon, Brushtox, and other “brush/tree & stump killers”. Mix at label rates for control.

Despite its attractiveness, Chinese Tallow is an insidious invader that has no place in either landscapes or natural areas. But with a little persistence and a quality control plan, you can rid your property of Chinese Tallow! For more information about invasive plant management and other agricultural topics, please contact your local UF/IFAS Extension office!

References:

Langeland, K.A, and S. F. Enloe. 2018. Natural Area Weeds: Chinese Tallow (Sapium sebiferum L.). Publication #SS-AGR-45. Printer friendly PDF version: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/AG/AG14800.pdf

by Mark Mauldin | Oct 23, 2020

Archery season for white tailed deer opens this Saturday (10/24/20) in FWC Hunting Zone D (basically the Panhandle west of Tallahassee, see figure 1). Before you go hunting be sure that you have a plan in place for logging and reporting your harvest. Last year FWC implemented a mandatory harvest reporting system. That system is still in effect this year but with some modifications.

Figure 1. FWC Hunting Zone D

myfwc.com

The most notable change to the harvest reporting system this year is with the associated smart phone app. There is a new app this year – Fish|Hunt Florida. This new app will replace the Survey123 for ArcGIS app that was used last year.

In my opinion, the logging and reporting function on the Fish|Hunt Florida app is simpler to use than the previous app. Additionally the Fish|Hunt Florida app has many other useful features. A few highlights include; the ability to view and purchase hunting and fishing licenses/permits through the app, interactive versions of hunting and fishing regulations, and several other handy resources for sportsmen including, marine forecasts, tides, wildlife feeding times, sunrise & sunset times, boat ramp locator and a current location feature. Screenshots from the app are included below. The Fish|Hunt Florida app is available for free through the Apple App Store and the Google Play Store.

Remember, the current regulations state that your deer harvest must be logged before the animal is moved. Take a minute or two to install the app on your phone before you go hunting. Using the app allows logging and reporting to happen simultaneously. The app can be used for logging and reporting a harvest even in areas where cell service is poor. Harvest information will can be saved and the app will automatically complete the process as soon as adequate cell service is available. The alternative to using the app is a two-step process, the harvest can be logged (prior to being moved) on a paper form and then reported by calling 888-HUNT-FLORIDA (888-486-8356) or going to GoOutdoorsFlorida.com within 24 hours.

Follow the link for specific instructions for logging and reporting a harvested deer using the Fish|Hunt Florida app; don’t worry, it’s easy. Fish|Hunt Florida app instructions

For more information on the Fish|Hunt Florida app and the FWC Deer Harvest Reporting System visit myfwc.com.

Screenshot of the Boat Info tab from the Hunt|Fish Florida App. Click on the image to make it larger.

Screenshot of the Fishing Tab from the Hunt|Fish Florida App. Click on the image to make it larger.

Screenshot of the Home screen from the Hunt|Fish Florida App. Click on the image to make it larger.

Screenshot of the Hunting tab from the Hunt|Fish Florida App. Click on the image to make it larger.

Take in a sunrise or sunset. The beach is often one of the best places to do this, but anywhere will do. Last weekend, I was at the Okaloosa Island Boardwalk and Pier and the sunset was magnificent. While there, take a walk along the beach, let the cool sand squish between your toes and discover what might be hiding in the wrack. The wrack is that line of seaweed deposited after high tide. Upon close inspection, it contains many treasures including seagrasses, sponges, shells, worm tubes, small crabs and other oddities.

Take in a sunrise or sunset. The beach is often one of the best places to do this, but anywhere will do. Last weekend, I was at the Okaloosa Island Boardwalk and Pier and the sunset was magnificent. While there, take a walk along the beach, let the cool sand squish between your toes and discover what might be hiding in the wrack. The wrack is that line of seaweed deposited after high tide. Upon close inspection, it contains many treasures including seagrasses, sponges, shells, worm tubes, small crabs and other oddities.