by Judy Biss | Mar 18, 2018

Adult grass carp, Ctenopharyngodon idella Val. Credit: Jeffrey E. Hill, University of Florida

Spring is only days away. Everywhere you look, plants of all kinds are awakening to recent rains, longer days, and fertile soils; and this includes aquatic plants as well! Florida has hundreds of aquatic plant species, and they are an often-overlooked feature of Florida’s landscape. Overlooked that is, until the growth of non-native (or even some native) species interferes with use of our waters. Some aquatic plant species can become problematic in Florida waters as their growth interferes with fishing, flood control, navigation, recreation, livestock watering, or irrigation. For these reasons, being knowledgeable about properly managing aquatic plants is important to the many uses of Florida’s waters, whether it be a state managed public waterbody, or your own backyard farm pond.

Any pest, whether plant, animal, or insect, is best managed using “IPM” or Integrated Pest Management. IPM involves using a variety of available management “tools” to control pests in an economically and environmentally sound manner. As in any IPM effort, the first thing to do is identify what is causing the problem. Next, define what your management goals are. Then, research what tools are available for you to manage the problem. And finally, devise and implement your management plan.

In this article, we will look at one of the IPM “tools” used to manage aquatic plants – the grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella Val.). The use of grass carp to manage problematic levels of aquatic plants falls under the general management term of “biological control.” Biological control essentially uses one living organism to control another living organism. Grass carp have become one of the most widely recognized examples of biological control.

The Grass Carp

As the name implies, the grass carp is an herbivorous fish that eats plants. It is native to eastern Russia and China living in large muddy rivers and associated lakes, and is actually one of the largest members of the minnow family. According to the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission the largest triploid grass carp taken in Florida was 15 years old, 56″ long and weighed 75 pounds! The grass carp has been introduced into more than 50 countries and is used as a food item in many places around the world. They are used in nearly all states of the USA to manage aquatic plants.

Introduction into the United States:

“The grass carp was considered for introduction into the U.S. primarily because of its plant-eating diet, which was thought to have great potential for the control of aquatic weeds. In 1963 the U.S. Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife Fish Farming Experiment Station, Stuttgart, Arkansas, in cooperation with Auburn University, imported grass carp for experimental purposes; in 1970, this fish was introduced into Florida primarily for researchers to study its ability to control hydrilla.” (Grass Carp: A Fish for Biological Management of Hydrilla and Other Aquatic Weeds in Florida). “Early release of diploid fish led to reproductive populations in several US drainage systems, including the Mississippi River and major tributaries” (Grass Carp, the White Amur: Ctenopharyngodon idella Cuvier and Valenciennes (Actinopterygii: Cyprinidae: Squaliobarbinae))

Development of the Sterile Triploid

According to the UF/IFAS publication, Grass Carp, the White Amur: Ctenopharyngodon idella Cuvier and Valenciennes (Actinopterygii: Cyprinidae: Squaliobarbinae), “Use of the fish was limited from 1970 until 1984 due to tight regulations surrounding concerns of escape and reproduction, and the potential impacts that colonization of the fish could have on native flora and fauna. These concerns led to research that developed a non-reproductive fish, which was equally effective in controlling hydrilla.” This non-reproductive fish is known as the triploid grass carp. Through a process of subjecting fertilized grass carp eggs to heat, cold, or pressure, the resulting fish have an extra set of chromosomes rendering the fish sterile. Triploid carp have the same herbivorous characteristics as the normal diploid carp, but they are unable to spawn and reproduce. Their inability to reproduce is what makes them a viable tool to manage aquatic plants, and that is because their numbers and feeding pressure can be controlled, they cannot overpopulate a waterbody, nor if they escape, will they overpopulate un-managed areas.

The growth of invasive non-native (or even some native) aquatic plant species can interfere with the many uses of Florida’s waters. This is invasive hydrilla mixed with water lilies in a Florida lake. Photo by Judy Biss

What kinds of aquatic plants do they eat?

The grass carp grazes on many types of aquatic plants, but it does have its preferences. Its most preferred aquatics plants are hydrilla, chara (musk grass), pondweed, southern naiad, and Brazilian elodea. Its least favorite aquatic plants are species such as water lily, sedges, cattails, and filamentous algae. It will, however, graze on many types of plants even shoreline or overhanging vegetation in the absence of its preferred foods. Another reason the grass carp is an effective plant management tool is because it eats many times its body weight in plant material. As stated in Grass Carp, the White Amur: Ctenopharyngodon idella Cuvier and Valenciennes (Actinopterygii: Cyprinidae: Squaliobarbinae), “every 1 lb. increase in fish weight requires 5–6 lbs. of dry hydrilla (Sutton et al. 2012), which—considering hydrilla is 95% water—is a great deal of live plant material.”

Use of Grass Carp as a Biological Control:

Integrating the use of grass carp in aquatic plant management plans is usually cost effective. In many cases involving the use of grass carp, overabundant aquatic weed infestations are first treated with an aquatic herbicide to reduce biomass. The carp are then stocked to control regrowth and to extend the time between herbicide treatments. This can be up to 5 or more years, depending on the situation. One factor in long term control is the survival of the stocked grass carp. They are not without predators as largemouth bass, otters, birds, etc. readily prey on small grass carp. Stocked fish should be at least 12 inches long to help avoid predation and provide plant control. Other considerations to factor into your management plans are the long term, yet non-specific, control that grass carp can provide. If not stocked in the correct manner, they may end up eating aquatic plants that you wish to maintain. Also, if they eat all the aquatic plants, your once clear water may become dominated by algae instead.

How can I get grass carp for my lake or pond?

The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) administers the Grass Carp program for Florida. A permit is required before you can purchase carp, and only the sterile triploid carp are permitted for use in Florida. The FWC can answer many questions about the use of grass carp and if this aquatic plant management “tool” is the right one for you to use in your particular situation. In north Florida, the regional FWC office is located at 3911 Highway 2321 Panama City, FL 32409, Phone: 850-767-3638.

What do I need to know about triploid grass carp?

Cost: Triploid grass carp cost between $5 and $15 each and are usually stocked at three to ten fish per acre, resulting in costs as low as $15 per acre. In comparison, herbicides cost between $100 and $500 per acre and mechanical control may cost more than twice that.

Time: Grass carp usually take six months to a year to be effective in reducing problem vegetation, although they provide much longer term control than other methods, often up to five years before restocking is necessary. When used in conjunction with an initial herbicide treatment, control of problem vegetation can be achieved quickly, and fewer carp are required to maintain the desired level of vegetation.

Overstocking: Once stocked in a lake or pond, carp are very difficult to remove. If overstocking occurs, it may be ten years or more before the vegetation community recovers. Even after carp are removed, other herbivores such as turtles may prevent the regrowth of vegetation.

Water Clarity: Aquatic plants remove nutrients in the water. When plants are removed, nutrients may then be utilized by phytoplankton, turning the water green. Clarity may be improved by reducing or eliminating sources of nutrients into the lake such as road runoff and lawn fertilizer.

Inflows/Outflows: It is in the best interest of people stocking carp to keep them in the desired lake or pond. It is also a required condition of the permit. Any inflows or outflows through which carp could escape into other waters require barriers to prevent fish from escaping into waters not permitted.

For more information on this topic, please see the following resources used for this article:

Aquatic and Wetland Plants in Florida

Plant Management in Florida Waters

Grass Carp, the White Amur: Ctenopharyngodon idella Cuvier and Valenciennes (Actinopterygii: Cyprinidae: Squaliobarbinae),

Grass Carp: A Fish for Biological Management of Hydrilla and Other Aquatic Weeds in Florida).

Chinese Grass Carp

FWC Triploid Grass Carp Permit

UF/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants – Aquatic Plant Control Methods

by Sheila Dunning | Jan 19, 2018

We plant trees with the intention of them being there long after we are gone. However, m any trees and shrubs fail before ever reaching maturity. Often this is due to improper installation and establishment. Research has shown that there are techniques to improve survivability. Before digging the hole:

any trees and shrubs fail before ever reaching maturity. Often this is due to improper installation and establishment. Research has shown that there are techniques to improve survivability. Before digging the hole:

- Look up. If there is a wire, security light, or building nearby that could interfere with proper development as it grows, plant elsewhere.

- Dig a shallow planting hole as wide as possible. Shallow is better than deep! Many people plant trees too deep. A hole about one-and-one-half the diameter of the width of the root ball is recommended. Wider holes should be used for compacted soil and wet sites. In most instances, the depth of the hole should be LESS than the height of the root ball, especially in compacted or wet soil. If the hole was inadvertently dug too deep, add soil and compact it firmly with your foot. .

- Find the point where the top-most root emerges from the trunk. If this is buried in the root ball then remove enough soil from the top so the point where the top-most root emerges from the trunk is at the surface. Burlap on top of the ball may have to be removed to locate the top root.

- Slide the plant carefully into the planting hole. To avoid damage when setting a large tree in the hole, lift the tree with straps or rope around the root ball, not by the trunk. Special strapping mechanisms need to be constructed to carefully lift trees out of large containers.

- Position the plant where the top-most root emerges from the trunk slightly above the landscape soil surface. It is better to plant a little high than to plant it too deep. Remove most of the soil and roots from on top of the root flare and any growing around the trunk or circling the root ball. Once the root flare is at the appropriate depth, pack soil around the root ball to stabilize it. Soil amendments are usually of no benefit. The soil removed from the hole and from on top of the root ball makes the best backfill unless the soil is terrible or contaminated. Insert a square-tipped balling shovel into the root ball tangent to the trunk to remove the entire outside periphery. This removes all circling and descending roots on the outside edge of the root ball.

- Straighten the plant in the hole. Before you begin backfilling have someone view the plant from two directions perpendicular to each other to confirm that it is straight. Break up compacted soil in a large area around the plant provides the newly emerging roots room to expand into loose soil. This will hasten root growth translating into quicker establishment Fill in with some more backfill soil to secure the plant in the upright position.

- Remove synthetic materials from around trunk and root ball. Synthetic burlap needs to be completely removed from the root ball; treated burlap can be left in place. String, strapping, plastic, and other materials that will not decompose and must be removed from the trunk at planting. Remove the wire above the soil surface from wire baskets before backfilling.

- Apply a 3-inch-layer of mulch. To retain moisture and suppress weeds cover the outer half of the root ball with an organic mulch. Do not cover the stem of the plant or the connecting root flare.

- Water consistently until established. For nursery stock less than 2-inches in caliper, this will require every other day for 2 months, followed by weekly 3-4 months. At each irrigation, apply 2 to 3 gallons of water per inch trunk caliper directly over the root ball. Never add irrigation if the ground is saturated.

by Carrie Stevenson | Jan 5, 2018

The ghost flower in full bloom. Photo credit: Carol Lord

Imagine you are enjoying perfect fall weather on a hike with your family, when suddenly you come upon a ghost. Translucent white, small and creeping out of the ground behind a tree, you stop and look closer to figure out what it is you’ve just seen. In such an environment, the “ghost” you might come across is the perennial wildflower known as the ghost plant (Monotropa uniflora, also known as Indian pipe). Maybe it’s not the same spirit from the creepy story during last night’s campfire, but it’s quite unexpected, nonetheless. The plant is an unusual shade of white because it does not photosynthesize like most plants, and therefore does not create cholorophyll needed for green leaves.

In deeply shaded forests, a thick layer of fallen leaves, dead branches, and even decaying animals forms a thick mulch around tree bases. This humus layer is warm and holds moisture, creating the perfect environment for mushrooms and other fungi to grow. Because there is very little sunlight filtering down to the forest floor, the ghost flower plant adapted to this shady, wet environment by parasitizing the fungi growing in the woods. Ghost plants and their close relatives are known as mycotrophs (myco: fungus, troph: feeding).

Ghost plant in bloom at Naval Live Oaks reservation in Gulf Breeze, Florida. Photo credit: Shelley W. Johnson

These plants were once called saprophytes (sapro: rotten, phyte: plant), with the assumption that they fed directly on decaying matter in the same way as fungi. They even look like mushrooms when emerging from the soil. However, research has shown the relationship is much more complex. While many trees have symbiotic relationships with fungi living among their root systems, the mycotrophs actually capitalize on that relationship, tapping into in the flow of carbon between trees and fungi and taking their nutrients.

Mycotrophs grow throughout the United States except in the southwest and Rockies, although they are a somewhat rare find. The ghost plant is mostly a translucent shade of white, but has some pale pink and black spots. The flower points down when it emerges (looking like its “pipe” nickname) but opens up and releases seed as it matures. They are usually found in a cluster of several blooms.

The next time you explore the forests around you, look down—you just might see a ghost!

by Carrie Stevenson | Jan 5, 2018

The swing hanging from our magnolia tree has provided many happy memories for our family. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson

Do you have a favorite tree? Often, the trees in our lives tell a story.

One of the selling points when we bought our house 14 years ago was the tall, healthy Southern magnolia in the front yard. It was beautiful, and I could see it out my front window. A perfect shade tree, I could envision a swing hanging from its branches one day. Within six months of moving into the house, Hurricane Ivan struck. A neighbor’s tree fell and sheared off a quarter of the branches from our beloved magnolia. We were lucky to have minimal damage otherwise, and hoped the tree would survive.

The branches and leaves eventually filled in, and we added that swing I had imagined. One day I was pushing my daughter in the swing, when a car slowed on our street and stopped at our mailbox. A man stepped out and asked, “Are you enjoying that tree?” I responded that we very much were, and with a smile, he explained that his family built our house and that he planted that very magnolia tree 40 years before, when his son was born. He was so happy to see us enjoying the tree that he could not help but stop.

I was so grateful to hear that story and know that our family’s favorite tree held such special meaning. Our enjoyment existed because of the joyous celebration of a new birth. That is why we plant trees. For the benefit of those yet unborn, to commemorate special moments, and to provide the very oxygen we breathe. As the Greek proverb goes, “Society grows great when old men plant trees whose shade they know they shall never sit in.”

January 19 is Florida’s Arbor Day, a time to celebrate the many benefits of trees, and the day is often celebrated by planting new trees. Winter is the best time of year to plant trees, as they are able to establish roots without competing with the energy needs of new branches and leaves that come along in springtime.

“The best time to plant a tree is twenty years ago. The second best time is now.” –Anonymous

Check with your local Extension offices, garden clubs, and municipalities to find out if there is an Arbor Day event near you! Several local agencies have joined forces to organize tree giveaway events in observance of Florida’s Arbor Day.

Escambia County:

Thursday, January 18:

Deadline for UF IFAS Extension/Escambia County’s second annual Arbor Day Mail Art Contest. To participate, mail a drawing, painting, or mixed media artwork with the theme, “Strong Trees, Strong Communities” to Arbor Day Art Contest c/o Escambia County Extension, 3740 Stefani Road, Cantonment, FL 32533. Please include your name, age, and contact information on the back of your artwork. Contest entries must arrive by mail or be dropped off by Jan. 18 and will be judged at the tree giveaway on Jan. 20 at Barrineau Park Community Center.

First place winners of the art contest will receive prizes including a seven-gallon tree, a shovel, and a tree book. Second place winners will receive a tree book and third place winners will receive gardening gloves. Categories include children (12-under), teen (13-18), and adult (over 18). All participants in attendance at the tree giveaway will receive a special edition Arbor Day water bottle featuring last year’s winning design.

Many communities plant trees to celebrate Arbor Day. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson

Saturday, January 20th

Escambia County will hold their tree giveaway and public planting from 10 a.m. to noon Saturday, Jan. 20 at Barrineau Park Community Center, located at 6055 Barrineau Park Road, Molino. Support for the event is provided by the Florida Forest Service, Resource Management Services, and Escambia County UF-IFAS Extension. Each attendee will receive two free native 1-gallon trees. Species available include tulip poplar, Chickasaw plum, Shumard oak, and fringetree.

For more information about either Escambia event, contact Carrie Stevenson, Coastal Sustainability Agent III, UF IFAS Extension, at 850-475-5230 or ctsteven@ufl.edu.

Santa Rosa County:

Friday, January 19

10 am—Navarre Garden Club Arbor Day celebration. Foresters will give away 1-gallon containerized trees and conduct a have tree planting demo. 7254 Navarre Parkway, Navarre, 32566. For more information, contact Mary Salinas, 850-623-3868 or maryd@santarosa.fl.gov

Saturday, January 20th

10 am—Milton Garden Club Arbor Day celebration. Foresters will give away 1-gallon containerized trees and conduct a have tree planting demo. 5256 Alabama Street, Milton. For more information, contact Mary Salinas, 850-623-3868 or maryd@santarosa.fl.gov

Leon County:

Saturday, January 20th

9am to 12pm – City of Tallahassee/Leon County Arbor Day Celebration – Join City and County Staff, UF/IFAS Leon County Extension Faculty and Master Gardener volunteers at the Apalachee Regional Park (7550 Apalachee Pkwy) for a tree planting in honor of Arbor Day. Citizens are invited to come help plant hundreds of trees in the park and also learn about the benefits of trees, how to properly plant a tree, and after the planting is done, take a tree identification walk. For more information, contact Mindy Mohrman, City/County Urban Forester at 850.891.6415 or melinda.mohrman@talgov.com

by Sheila Dunning | Dec 15, 2017

According to Druid lore, hanging the plant in homes would bring good luck and protection. Holly was considered sacred because it remained green and strong with brightly colored red berries no matter how harsh the winter. Most other plants would wilt and die.

Later, Christians adopted the holly tradition from Druid practices and developed symbolism to reflect Christian beliefs. Today, the red berries are said to represent the blood that Jesus shed on the cross when he was crucified. Additionally, the pointed leaves of the holly symbolize the crown of thorns Jesus wore on his head.

Later, Christians adopted the holly tradition from Druid practices and developed symbolism to reflect Christian beliefs. Today, the red berries are said to represent the blood that Jesus shed on the cross when he was crucified. Additionally, the pointed leaves of the holly symbolize the crown of thorns Jesus wore on his head.

Several hollies are native to Florida. Many more are cultivated varieties commonly used as landscape plants. Hollies (Ilex spp.) are generally low maintenance plants that come in a diversity of sizes, forms and textures, ranging from large trees to dwarf shrubs.

The berries provide a valuable winter food source for migratory birds. However, the berries only form on female plants. Hollies are dioecious plants, meaning male and female flowers are located on separate plants. Both male and female hollies produce small white blooms in the spring. Bees are the primary pollinators, carrying pollen from the male hollies 1.5 to 2 miles, so it is not necessary to have a male plant in the same landscape.

Several male hollies are grown for their compact formal shape and interesting new foliage color. Dwarf Yaupon Hollies (Ilex vomitoria ‘Shillings’ and ‘Bordeaux’) form symmetrical spheres without extensive pruning. ‘Bordeaux’ Yaupon has maroon-colored new growth. Neither cultivar has berries.

Hollies prefer to grow in partial shade but will do well in full sun if provided adequate irrigation. Most species prefer well-drained, slightly acidic soils. However, Dahoon holly (Ilex cassine) and Gallberry (Ilex glabra) naturally occurs in wetland areas and can be planted on wetter sites.

Evergreen trees retain leaves throughout the year and provide wind protection. The choice of one type of holly or another will largely depend on prevailing environmental conditions and windbreak purposes. If, for example, winds associated with storms or natural climatic variability occur in winter, then a larger leaved plant might be required.

The natives are likely to be better adapted to local climate, soil, pest and disease conditions and over a broader range of conditions. Nevertheless, non-natives may be desirable for many attributes such as height, growth rate and texture but should not reproduce and spread beyond the area planted or they may become problematic because of invasiveness.

There is increasing awareness of invasiveness, i.e., the potential for an introduced species to establish itself or become “naturalized” in an ecological community and even become a dominant plant that replaces native species. Tree and shrub species can become invasive if they aggressively proliferate beyond the windbreak. At first glance, Brazilian pepper (Schinus terebinthifolius), a fast-growing, non-native shrub that has a dense crown, might be considered an appropriate red berry producing species. However, it readily spreads seed disbursed by birds and has invaded many natural ecosystems. Therefore, the Florida Department of Environmental Protection has declared it illegal to plant this tree in Florida without a special permit. Consult the Florida Exotic Pest Plant Council’s Web page (www.fleppc.org) for a list of prohibited species in Florida.

For a more comprehensive list of holly varieties and their individual growth habits refer to ENH42 Hollies at a Glance: http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/mg021

by Judy Biss | Mar 17, 2017

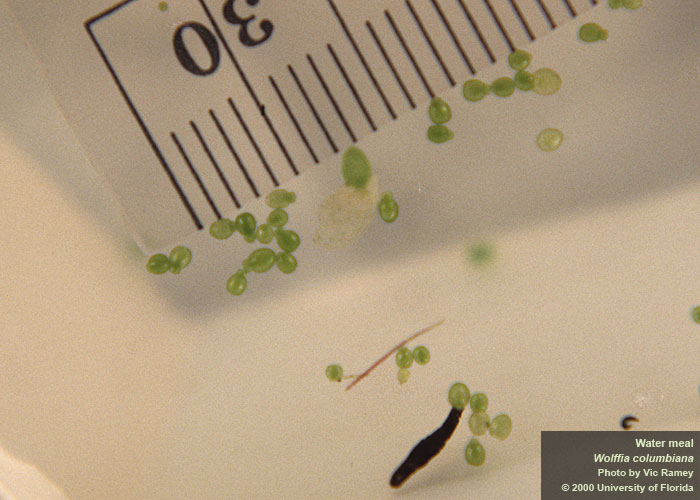

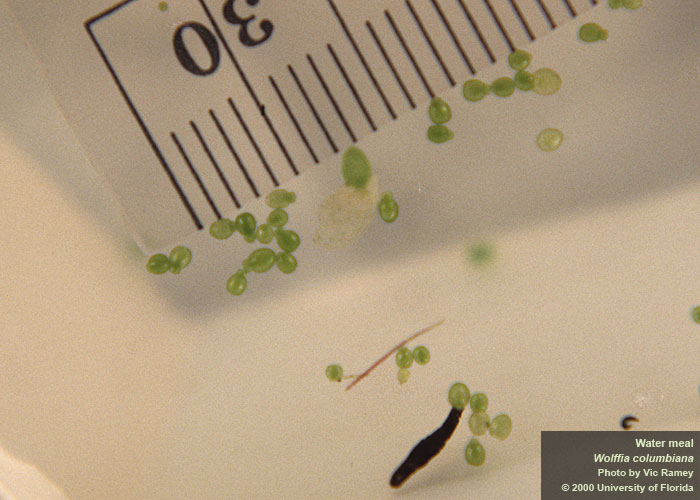

Water meal, the world’s smallest flowering plant. Photo by Vic Ramey, University of Florida/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Used with permission.

Some of the world’s smallest flowering plants grow in aquatic environments. And a number of these tiny aquatic plants grow natively right here in Florida! Aquatic plants of all kinds display an amazing array of adaptations for growing in water. They can tolerate drought, flood, flowing water, stagnant water, cold spring runs, and warm brackish marshes. They grow in sun and shade and nutrient rich to nutrient poor waters. Some of their adaptations include the ways in which they grow such as being rooted in bottom sediments, submerged, emerged, leaves floating on the surface, or completely free floating with their roots dangling into the water below.

The tiniest of aquatic plants are in this group of free floating plants. Let’s take a look at five of these tiny (less than ½ inch wide) plant species in Florida. They are most noticeable in slow moving waters, ponds, or coves protected from wind where many thousands of them form floating mats almost like paint on the water surface. Even though individual plants are small, some of these plant species are used by wildlife and invertebrates for food and cover. Oftentimes, especially in small ponds, these tiny floating plants can cover the entire water surface resulting in the need for management, especially if the ponds are used for irrigation or livestock watering.

In this article we will look at the native species, but as you are probably aware, there are also non-native representatives of these tiny plants established in our waters, but that is a story for another time…

The images and text below are from the UF/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Species website, list of Plants Sorted by Common Name.

Watermeal

“Water meal, native to Florida, is a tiny, floating, rootless plant. At 1 to 1.5 mm long, it is the smallest flowering plant on earth. It is occasionally found growing in rivers, ponds, lakes, and sloughs of the peninsula and central panhandle of Florida (Wunderlin, 2003).”

Water meal has a grainy feel and can be used as one clue in identifying this plant. Photo by Ann Murray, University of Florida/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Used with permission.

American Waterfern

“There are six species of Azolla in the world. American waterfern is the species commonly found in Florida. American waterfern is a small, free-floating fern, about one-half inch in size. It is most often found in still or sluggish waters. Young plants are, at first, a bright or grey-green. Azolla plants often turn red in color. American waterfern can quickly form large, floating mats.”

A large area of waterfern showing the reddish coloration. Photo by Vic Ramey, University of Florida/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Used with permission.

Close up of individual water fern plants. Photo by Ann Murray, University of Florida/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Used with permission.

Giant Duckweed

“Giant duckweed is a native floating plant in Florida. Though very small, it is the largest of the duckweeds…..frequently found growing in rivers, ponds, lakes, and sloughs from the peninsula west to the central panhandle of Florida (Wunderlin, 2003)… Giant duckweed has two to three rounded leaves, which are usually connected. Giant duckweeds usually have several roots (up to nine) hanging beneath each leaf. The underleaf surface of giant duckweed is dark red.”

Close up of individual duckweed plants showing roots hanging freely below the plant. Photo by Vic Ramey, University of Florida/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Used with permission.

A typical scene of duckweed in a quiet cove or pond. Photo by Ann Murray, University of Florida/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Used with permission.

Small Duckweed

“Small duckweeds are floating plants. They are commonly found in still or sluggish waters. They often form large floating mats…. Small duckweeds are tiny (1/16 to 1/8 inch) green plants with shoe-shaped leaves. Each plant has two to several leaves joined at the base. A single root hangs beneath.”

This is small duckweed, note the single root below each plant. Photo by Vic Ramey, University of Florida/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Used with permission.

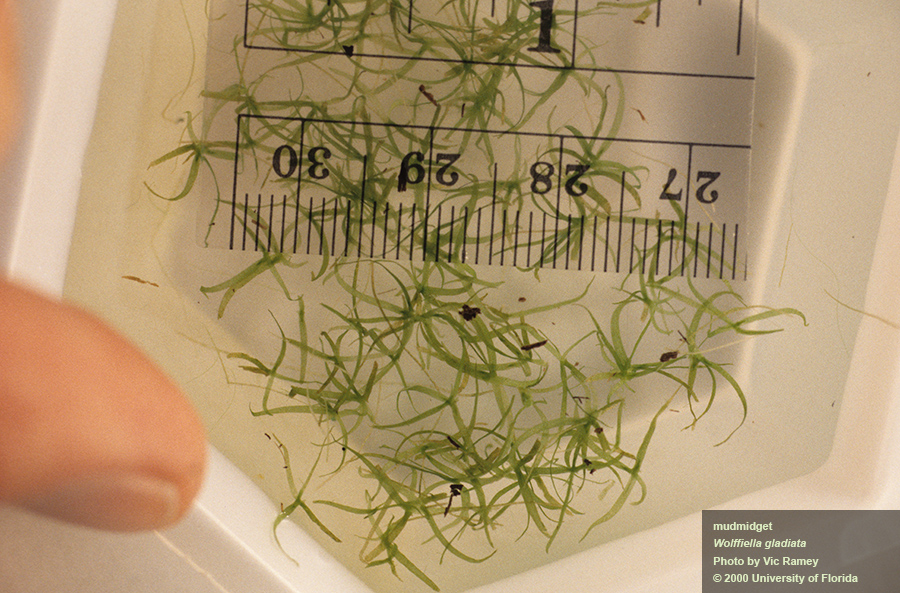

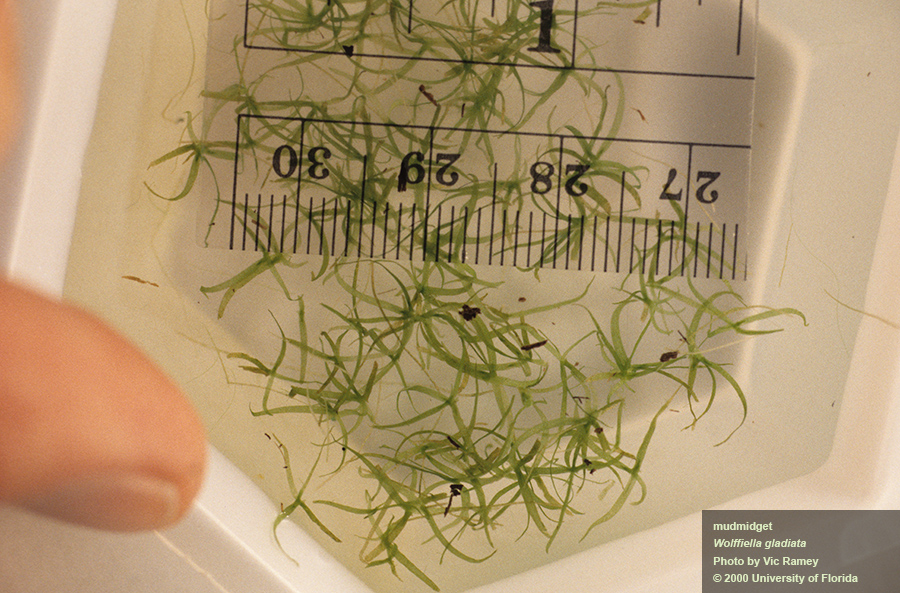

Mudmidget

“Mud-midget, native to Florida, is another small duckweed, but this one has narrow, elongated fronds. The fronds are usually connected to form starlike colonies. The fronds are 5-10 mm long; the flowers are extremely small and difficult to see. Mud-midget plants float just beneath the surface of the water and is frequently found growing in rivers, ponds, lakes, and sloughs from the peninsula west to the central panhandle of Florida (Wunderlin, 2003)….”

Mudmidget, Photo by Vic Ramey, University of Florida/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Used with permission.

If you have any questions about aquatic plant identification or management options, please contact your local UF/IFAS Extension County office. And, for more information on Florida’s aquatic plants, please see the following resources used for this article:

UF/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Species

Plants Sorted by Common Name

USDA Forest Service – Duckweed

USDA Forest Service – Water Fern

Native Aquatic and Wetland Plant Fact Sheets

Aquatic Plant Identification List with Pictures and Videos