by Rick O'Connor | Aug 11, 2017

A variety of plastics ends up in the Gulf. Each is a potential problem for marine life. Photo: Rick O’Connor

Since the early 1970’s, when Chief Iron Eyes Cody shed a tear on a television commercial, we have been trying to reduce the amount of solid waste found along our beaches and within our waters. Though numerous agencies and civic groups, led by the Ocean Conservancy, have held beach and underwater clean ups over the last few decades, the problem still exist.

However, we can say this – the problems have changed. Many groups collect data while they collect the debris to determine what, and how much, has been collected. This information can give folks an idea of what the major issues are. Because of this data, aluminum can pull-tabs and glass bottles are not as common as they once were. Communities saw they were a large problem and either removed them from the market or developed ordinances that banned them from beaches – this is certainly a success story. There are agencies and researchers who compile solid waste data to let people know what they are throwing away. Once we know this, we can be more effective at reducing marine debris.

Solid waste is not just a problem for coastal beaches; it is problem throughout society. Landfills will fill up, and communities will then need another location, or a new method, to dispose of it. Though the human growth rate has declined from 1.23% to 1.11% in the last decade, we are still growing and are currently at 7.5 billion humans on the planet. Each human will require resources to survive and, thus, will generate waste that will need to be disposed of. According to a paper published in 1990, humans were generating about 550 pounds of solid waste/person/year, which generated 1.3 billion tons of solid waste each year. In 2009 that increased to 2.3 billion tons.

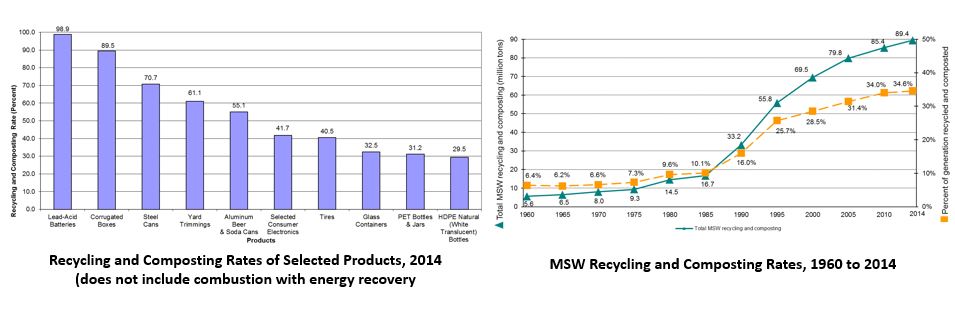

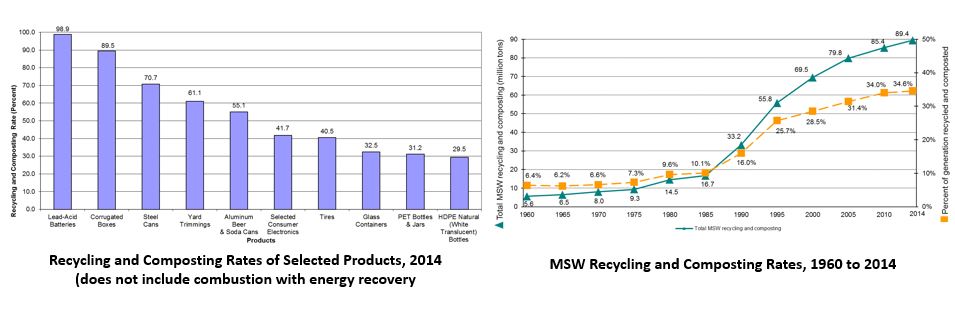

So how much of this solid waste is being recycled?

According to the U.S. EPA, 258 million tons of municipal solid waste was generated in the United States in 2014. 89 million tons (34%) was recycled. This is an increase from the 30% reported in many environmental science textbooks 10 years ago and <20% 20 years ago. Some states are doing much better than the national average, Washington reports they are now recycling 51.4% of their solid waste, and some nations are recycling more than 90% – so things are improving but there is room for improvement.

Recycling trends in the United States.

Source: U.S. EPA

What is the situation in the Pensacola Bay area?

A non-profit organization called Ocean Hour cleans selected beaches for one hour every weekend. The team coordinates volunteers to help collect the debris by providing buckets, tongs, and gloves; they also dispose of the waste. Part of their mission is to provide data on what they are collecting so that the community is aware of what their largest problems are. Based on their data the top three items reported by volunteers for each year were:

| Year |

#1 Item |

#2 Item |

#3 Item |

| 2015

|

Cigarette butts |

Food wrappers |

Plastic bottles |

| 2016 |

Plastic bottles |

Aluminum cans |

Cigarette butts

Foam |

| 2017 (to date)

|

Cigarette butts |

Food wrappers |

Plastic and foam pieces |

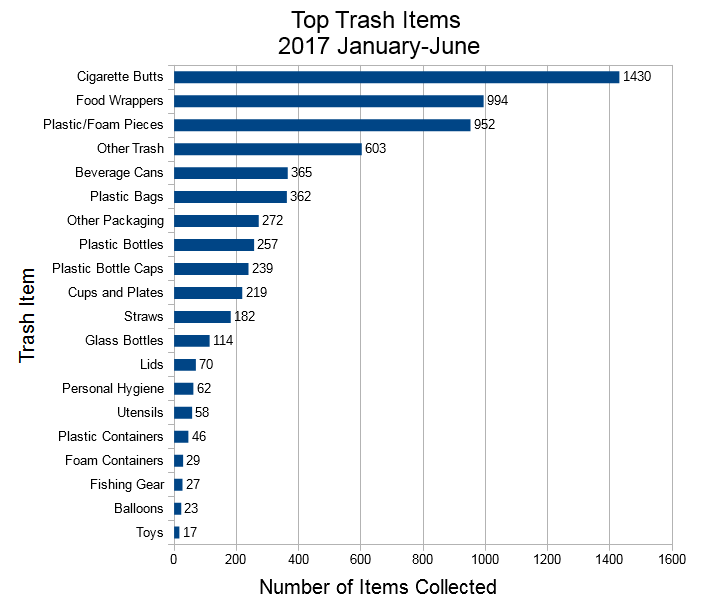

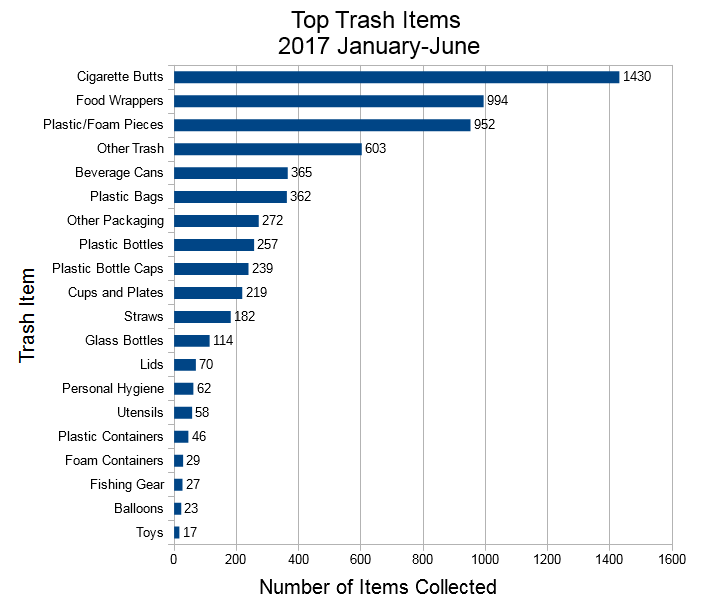

The graph produced from Ocean Hour’s data by Escambia County Division of Marine Resource Intern Ethan Barker, shows all of the items they have collected this year but the bulk of it is associated with smoking and eating. Marine biologist and artist Shelly Marshall used 1200 cigarette butts collected by the Ocean Hour team to create a 3-foot sea turtle she calls CIG. She then used plastic bottles and plastic bottle caps, again collected by Ocean Hour, to create a 5-foot “bottle”nose dolphin called CAP. Both of these pieces of marine debris art are displayed at different locations in the community, and at community events, to educate the public about our marine debris problems.

Marine debris collected by Ocean Hour during the first half of 2017.

Image: Ethan Barker

So what do we do about it?

That is really up to us. Again, agencies, researchers, and non-profits have been reporting on the problem for almost five decades now. We will continue to produce waste, not much can be done there, but the question is what we will do with it. The obvious answer is dispose of properly and recycle when we can.

Cigarette Butts

- If you are a smoker, please dispose of your cigarette butt properly. There are “pocket ash trays” some folks use to keep the butt with them until they can find a place to dispose of it.

Food Wrappers – Foam

Much of the debris is related to eating – wrappers, plastic film, foam cups, straws, etc. Much of what we find is associated with this activity.

- You can use your own cup and not the foam cups provided by food establishments

- You can bring your own container to take leftovers home

- If you have to purchase food and drink with all of the wrappers and foam, and I understand that there are times you must, then do your best to dispose of properly.

Ocean Hour will continue their efforts to remove the debris from area beaches. If you can, volunteer to help now and then. You can find their schedule at https://www.oceanhourfl.com/.

If Ocean Hour is not conducting a clean up in your area, consider having your own. The Ocean Hour team can assist with the logistics of how to conduct one.

Again, we are not going to stop waste production – but maybe we can do better with waste disposal.

CIG is a sea turtle created by artist Shelly Marshall using 1200 cigarette butts collected by Ocean Hour in a 40 minute period on Pensacola Beach.

Photo: Cathy Holmes

CAP is a 4-5′ bottlenose dolphin created by artist Shelly Marshall from plastic bottles and bottle caps collected by Ocean Hour on Pensacola Beach.

Photo: Shelly Marshall

Resources:

Advancing Sustainable Materials Management: Facts and Figures. 2017. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. https://www.epa.gov/smm/advancing-sustainable-materials-management-facts-and-figures.

Al-Salem, S.M., P. Lettieri, J. Baeyens. 2009. Recycling and Recovery Routes of Plastic Solid Waste (PSW): A Review. Waste Management. Vol 29 (10). Pp. 2625-2643. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0956053X09002190.

Miller, G.T., S.E. Spoolman. 2011. Living in the Environment; Concepts, Connections, and Solutions. Brooks/Cole Publishing. Belmont CA. 16th edition. Pp. 674.

Solid Waste Recycling. 2016. Department of Ecology. State of Washington. http://www.ecy.wa.gov/beyondwaste/bwprog_swDiverted.html.

Sullivan, C. 2017. Human Population Growth Creeps Back Up. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/human-population-growth-creeps-back-up/.

WorldoMeters. 2017. http://www.worldometers.info/world-population/.

by Ray Bodrey | May 21, 2017

Hurricane season begins this year on June 1st and ends November 30th. As Floridians, we face the possibility of hurricanes each year. This simply goes with the territory. During these months, it’s important to plan for the threat of a hurricane, and at the same time hope, it never happens.

First and foremost, you may be asked to leave your home in emergency conditions. Emergency management officials would not ask you to do so without a valid reason. Please do not second guess this request. Leave your home immediately. Requests of this magnitude will normally come through radio broadcasts and area TV stations.

Figure 1. UF/IFAS Disaster Handbook.

Credit. UF/IFAS Communications.

The most important thing to keep in mind is to have your own, up to date plan for a possible evacuation. The University of Florida has developed, “The Disaster Handbook” to help citizens plan for safety. The handbook includes a chapter dedicated to hurricane planning. The chapter can be downloaded in pdf at http://disaster.ifas.ufl.edu/chap7fr.htm.

Utilizing the 15 principles below will assist you in your evacuation planning efforts:

- Know the route & directions: keep a paper state map in your vehicle. Be prepared to use the routes designated by the emergency management officials.

- Local authorities will guide the public: Stay in communication with local your local emergency management officials. By following their instructions, you are far safer.

- Keep a full gas tank in your vehicle: During a hurricane threat, gas can become sparse. Be sure you fill your tank in advance of the storm.

- One vehicle per household: If evacuation is necessary, take one vehicle. Families that carpool will reduce congestion on evacuation routes.

- Powerlines: Do not go near powerlines, especially if broken or down.

- Clothing: Wear clothing that protects as much area as possible, but suitable for walking in the elements.

- Disaster Kit: Create a kit complete with a battery powered NOAA weather radio, extra batteries, food, water, clothing and first aid kit. The kit should have enough supplies for at least three days.

- Phone: Bring your cell phone & charger.

- Prepare your home before leaving: Lock all windows & doors. Turn off water. You may want to turn off your electricity. If you have a home freezer, you may wish not too. Leave your natural gas on, unless instructed to turn it off. You may need gas for heating or cooking and only a professional can turn it on once it has been turned off.

- Family Communications: Contact family and friends before leaving town, if possible. Have an out of town contact as well, to check in with regarding the storm and safety options.

- Emergency shelters: Know where the emergency shelters are located in your vicinity.

- Shelter in place: This measure is in place for the event that emergency management officials request that you remain in your home or office. Close and lock all window and exterior doors. Turn off all fans and the HVAC system. Close the fireplace damper. Open your disaster kit and make sure the NOAA weather radio is on. Go to an interior room without windows that is ground level. Keep listening to your radio or TV for updates.

- Predetermined meeting place: Have a spot designated for a family meeting before the imminent evacuation. This will help minimize anxiety and confusion and will save time.

- Children at school: Have a plan for picking up children from school and how they will be taken care of and by whom.

- Animals and pets: Have a plan for caring for animals and shelter options in the event of an evacuation. For livestock, contact your local county extension office.

Following these steps will help you stay safe and give you a piece of mind, during hurricane season. Contact your local county extension office for more information.

Supporting information for this article can be found in the UF/IFAS EDIS publication, “Hurricane Preparation: Evacuating Your Home”, by Elizabeth Bolton & Muthusami Kumaran: http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/FY/FY74700.pdf

UF/IFAS Extension is An Equal Opportunity Institution.

by Ray Bodrey | Apr 26, 2017

Floods are a common concern in many areas of the U.S. Gulf coastal residents should be particularly aware. Floods may come in the form of flash floods, which come with little warning. Other flood conditions come on slower, as with large thunder storm fronts and tropical storms. With hurricane season not far away, it’s a good time to think about your property and the floodplains in your area.

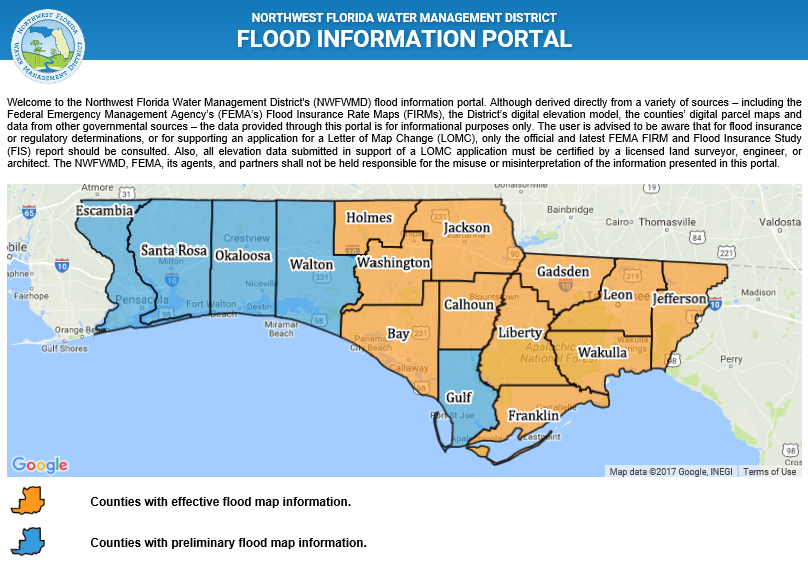

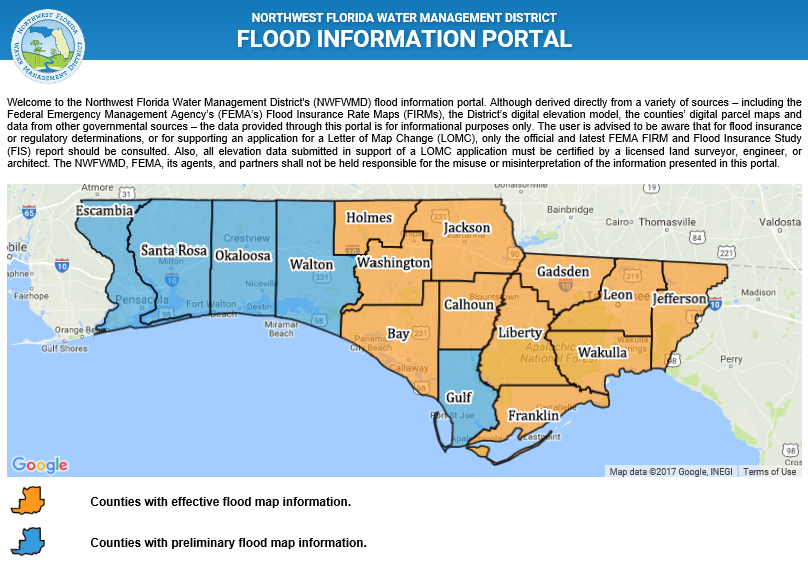

Figure: Flood Information Portal.

Photo: Courtesy of the Northwest Florida Water Management District.

Floodplains are broadly defined as land susceptible to flooding by any source. Areas designated as flood hazard areas are known also as “base flood” or “100-year-flood” zones. However, this can be confusing to some. A 100-year-floodplain does not mean that once your property floods, you’ll most likely not see it flood again for 100 years. The calculation actually means that there is a 1% chance that flooding will occur in any year. Floodplains are calculated by statistical estimates based on historical storm data.

Most mortgage lending agencies and banks, as well as real estate and insurance companies are well informed sources regarding floodplain information. Floodplain maps are updated periodically and are available for the public online and in print. FEMA’s National Flood Insurance Program has recently revised the digital flood insurance rate maps for many counties in Florida.

The Northwest Florida Water Management District (NWFWMD) offers a great tool for us in the Panhandle. The NWFWMD has created a map website, known as the “Flood Information Portal”. This site is dedicated in showing the extent of areas of flood risks. The site is also helpful in determining flood insurance rates and building requirements. The site is very user friendly with a search function, where one can search for floodplain information for a specific address. A detailed report can also be generated showing both the effective and preliminary flood map for the particular address selected. The map website can be found at http://portal.nwfwmdfloodmaps.com. For more information please contact your local county extension office and county, or city, planning department.

Before a flood strikes, find out if buying flood insurance is right for you. If you are in an areas prone to flooding already, consider modifying your home to combat any future flooding issue. If you believe your property is at risk, please be prepared. Keep in mind that flooding in an area can lead to street closures, power outages and temporary reduction in public services.

Supporting information for this article can be found in, “The Disaster Handbook” at the UF/IFAS web address: http://disaster.ifas.ufl.edu/

UF/IFAS Extension is An Equal Opportunity Institution.

by Jennifer Bearden | Mar 3, 2017

Kudzu bugs on soybeans. Photo credit: Jennifer Bearden

A few years ago, Florida is extended a warm welcome to a new pest – The Kudzu Bug! The kudzu bug was first documented in the US in 2009 in Northeast Georgia. It has quickly spread throughout the southeast.

At first, a pest that attacks kudzu sounds pretty good but this bug also attacks wisteria, figs, and other legumes like beans and peas. It is a serious pest to soybeans that are grown in our area. They are similar to stink bugs and discharge an odor when disturbed. Skin and eye irritation can occur from this odor emission.

Kudzu bugs are small (3.5-6mm long), and are rounded oblong in shape, and olive-green in color. They lay egg masses in two rows of 13 to 137 eggs per row. The first generation of kudzu bugs seem to prefer to feed on kudzu but subsequent generations will feed on and lay eggs on other legumes. When fall comes, the adults over-winter where they can find shelter. They crawl under tree bark and into cracks in houses.

If kudzu bugs make their way into your home, you can vacuum them up and dispose of them. If they are in your landscape or garden, you can set up a trap using a bucket of soapy water and a piece of white poster board. Kudzu bugs are attracted to lighter colors. To make the trap, cut the poster board in half. Attach the two halves by cutting a line up the middle of the two pieces and inserting them into each other. They should be in the shape of a plus sign. Place the board over the bucket of soapy water. As the insects hit the board, they will fall into the soapy water and drown.

Insecticides can be used but timing and placement are very important. Right now, kudzu bugs are just becoming active making now a good time to spray kudzu host plants with an insecticide. Insecticide with active ingredients ending in “-thrin”, such as pyrethrin, cyfluthrin, etc., are effective against kudzu bugs. Always read and follow label directions and precautions when using any pesticide. Controlling kudzu near your house will help decrease the number of bugs, but they are strong flyers and can migrate through neighborhoods that aren’t near kudzu.

Kudzu bug infected with Beauveria bassiana. Photo credit: Jennifer Bearden

There are some natural enemies of kudzu bugs! Generalist predators like green lacewings, lady beetles, damsel bugs and big eye bugs will attack kudzu bug nymphs. There are also two parasitoids that attack them. Both discovered in 2013, there is a tiny wasp that develops in the kudzu bug eggs and a fly that lays its eggs in the adult kudzu bug. The Kudzu bug, like other exotic invasive insect, are opportunistic and we have yet to see how many different plants species may serve as a host for this pest. Beauveria bassiana has also been found to infect kudzu bugs and seem to be an effective natural enemy.

For more information on the kudzu bug, contact the UF/IFAS Extension Office in your county.

by Carrie Stevenson | Mar 2, 2017

Guest Blogger – Dr. Steve A. Johnson, Associate Professor & Extension Specialist, Department of Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, University of Florida

Cuban Treefrog. Photo credit: Steve Johnson

The National Invasive Species Council defines an invasive species as one that is introduced outside its native range where it causes harm (or is likely to) to the environment, economy, or human quality of life. The Cuban Treefrog in Florida qualifies as invasive under all three parts of this definition. Introduced from Cuba to Key West inadvertently in a shipment of cargo about 100 years ago, this frog is now established throughout Florida’s peninsula, and isolated records from numerous panhandle counties continue to accumulate. There are many records of Cuban Treefrogs from other states in the US, and even Canada. Most of these frogs originated in Florida and found their way to points beyond as hitchhikers on vehicles or as stowaways in shipments of ornamental plants. Fortunately, Cuban Treefrogs do not appear to have gained a permanent foothold—yet—outside of the Sunshine State.

Cuban Treefrog eating a Green Treefrog. Photo Credit: Nancy Bennett

Cuban Treefrogs are well documented predators of Florida’s native treefrogs and are likely responsible for declines in native treefrog numbers, especially in suburban neighborhoods. Fortunately, research has shown that when native frogs (e.g., Squirrel and Green Treefrogs) are still present that they respond favorably to the removal of their invasive cousins. Cuban Treefrogs are known to seek shelter in electrical utility equipment or even a home air-conditioning units, and as they climb around they may cause short circuits, leading to costly repairs. They also invade homes, ending up in a toilet at times, and have also sent young children to the emergency room. The frogs exude a noxious skin secretion when handled, which is extremely irritating to mucous membranes, especially one’s eyes. So be sure to wash your hands thoroughly after handling a Cuban Treefrog.

To mitigate the negative impacts Cuban Treefrogs are having on Florida’s native wildlife, as well as their effects on our quality of life, I recommend that these invaders be captured and humanely euthanized. For tips on how to capture, identify, and humanely euthanize these frogs visit http://ufwildlife.ifas.ufl.edu/ and also read “The Cuban Treefrog in Florida”. Report sightings of this species outside of the Florida peninsula to Dr. Steve A. Johnson, and within the peninsula report them on EDDmapS.

by Rick O'Connor | Mar 2, 2017

Beach Vitex Blossom. Photo credit: Rick O’Connor

Research shows that the most effective time to deal with an invasive species, both in terms of controlling or eradicating the species and money spent to do so, is early on…. What we call Early Detection Rapid Response. Beach vitex is a good candidate for this.

The first record for vitex in the Florida panhandle was in 2012. A local citizen in Gulf Breeze (Santa Rosa County) reported it on her beach and believed it may have come from Santa Rosa Island… it did. The barrier island location was logged on EDDmaps and the Gulf Breeze plants were removed. A quick survey of Florida on EDDmaps found that the only other location was in Duval County – 3 records there. So this was not a wide spread plant in our state and could be a rare case for eradication. That was until I surveyed Pensacola Beach on a bicycle and found 22 properties with it. Soon afterwards, it was found on the shores of Perdido Bay and concern set it that it might be more widespread than we thought.

Vitex beginning to take over bike path on Pensacola Beach. Photo credit: Rick O’Connor

We tried to educate the property owners about the issue based on what we learned in South Carolina, where there is a state task force to battle the plant, and suggested methods of removal. Many property owners began the process, which can take several treatments over several years, and, with the help of University of West Florida students, removed all of the vitex from public land on Santa Rosa Island. We were feeling good that we might still be able to eradicate this plant from our county… and then I went for a hike in the Gulf Islands National Seashore… yep… found more… almost 10,000 m2 of the plant. UWF and Sea Grant have worked hard over the past year to remove these plants, and have removed all but one section. Recently I received an email letting me know that it was found in Franklin County. They have since logged this on EDDmaps and have begun the removal process. However, this begs the question… where else might this plant be in the panhandle?

Beach vitex (Vitex rotundifolia) is a salt tolerant plant that does well in dry sandy soils and full sun; it loves the beach. We have found it in dune areas above the high tide line. It was brought to the United States in the 1950’s for herbarium use. By the 1980,’s the plant was used in landscaping and sold at nurseries. It was first used in dune restoration in South Carolina after Hurricane Hugo, and that was when the trouble began.

Vitex growing at Gulf Islands National Seashore that has been removed. Photo credit: Rick O’Connor

The plant grows very aggressively during the warmer months. It out competes native dune plants and quickly takes over. Growing 2-3 foot tall, this woody shrub has above ground rhizomes that can extend over 20 feet. Secondary roots begin to grow from the nodes along these rhizomes and it quickly forms an entangled mat of vines that blocks sun for some of the native plants. There has also been concern for nesting sea turtles. The rhizomes can over take a nest while incubation is occurring and entrapping the hatchlings. The plant has become such a problem in both North and South Carolina that a state task force has been developed to battle it. Vitex can spread either vegetative or by seed, both can tolerate being in salt water and can be dispersed via tides and currents. The plant has 1-2” ovate leaves and violet colored blossom, which can be seen in late spring and summer. The leaves become a rusty gray color during winter. The seeds, which are found in late summer and fall, are spherical and gray-purple in color. Vitex produces many seeds, an estimated 22,000/m2, and – in addition to being carried by the tide – can be transported by birds as well.

Again, we are hoping that the plant has been discovered early enough to control, if not eradicate, it… HOWEVER, WE NEED YOUR HELP. If you think you may have seen this plant along your coasts, please contact your county Sea Grant Extension Agent for advice on how to manage it.